Abstract

The article uses a working hypothesis based on three assumptions, namely that democratisation is directly and positively correlated with conflict resolution/prevention; that socio-economic development is directly and positively correlated with democracy; and therefore that democratisation and socio-economic development provide a fitting structural basis for resolving and preventing conflict.

Firstly, the nature of conflict resolution is examined in the context of four categories. For the purpose of the discussion, the behaviouralist and instrumentalist/structuralist approaches are used. Secondly, the relationship between democracy and economic development is investigated. Research conclusions indicate that with regard to democratic regimes, economic development is a more important variable than political legacy, religious or linguistic factors. High growth and loss of personal income are potential threats to democratic consolidation and stability, and egalitarian income distribution is conducive to democratic durability. Data from African countries are used to test these general conclusions. These data qualify the correlation between growth and democracy, and shift the focus more to the social impact of growth and away from growth per se. Income and human development indices provide even less confirmation of the development/democracy correlation. Thirdly, the nature of democracy is briefly analysed to determine how development and conflict resolution can fit into its composition. The instrumentalist and intrinsic approaches are used.

The overall conclusion is that neither democratisation nor economic development, nor a combination of them can be applied under all circumstances for conflict resolution.

1. An Elusive Correlation?

In the late 20th century the end of the Cold War created expectations of a more peaceful world, and one in which democratisation is more prevalent. It was expected that Huntington’s ‘third wave’ (Huntington 1991), in symbolic terms, would meet with Fukuyama’s ‘end of history’ (Fukuyama 1989). Ideology was the cause of conflict while democracy is the guarantee against it.

Normative and qualitative assertions (like the ‘end of history’ or structural analyses of society) present us with the view that democracy is one of the most assured guarantees against conflict. Moreover, the ‘democratic peace’ assumption predicates that democratic societies do not engage in conflict with each other (Brown et al. 1996, Elman 1999:87-103, Chernoff 2004:49-77). A third dimension can be added to the correlation. Socio-economic development is considered to be either a catalyst for democratisation, or a consequence of democratisation. It presents us with a triad of assumed correlations, namely:

- that democratisation (including good governance) is directly and positively correlated with conflict resolution/prevention (Reychler 1999);

- that socio-economic development is directly and positively correlated with democracy;

- and therefore, that democratisation and socio-economic development provide a necessary structural basis for resolving deep-rooted conflicts or for preventing conflicts.

For the purpose of this article these assumed correlations serve as a working hypothesis. Concrete illustrations of the practical relevance of this hypothesis are the following. The World Bank has embraced it, it has been incorporated in the ‘Copenhagen criteria’ for European Union (EU) membership (http://europa.eu.it/comm/enlargement/intro/criteria.html) and in the context of the ‘Declaration on Democracy, Political, Economic and Corporate Governance’ of the new African Union and the New Partnership for Africa’s Development (NEPAD). The World Bank’s package of conditionalities includes concepts like good governance and multi-party democratisation, as well as economic structural adjustment. In its view, structural adjustment, or now Poverty Reduction Strategies (http://www.worldbank.org/ESSD/sdvext.hsf/67ByDocName/ConflictAnalysisPovertyReductionStrategyPapersPRSPinconflict-affectedcountries) can serve as the blueprint for socio-economic development. The third component (conflict) is implied in reconstructing the state. A predatory state or a state without the necessary institutional capacity is often the cause of conflict. This view about a properly institutionalised state was the focus of the World Bank’s World Development Report, The State in a Changing World, in 1997.

Much research has already been conducted about the relationship between democracy and development (for example, Przeworski et al 2000, Quinn & Woolley 2001, Przeworski 1991, Freedom House, Iheduru 1999, Przeworski & Limongi 1993, Landa & Kapstein 2001). Similar research about a relationship between democracy and development on the one hand, and conflict resolution on the other hand, is not so readily available.

A notable, practical example where this triad of correlations is embraced, is the view of the Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency (SIDA) on humanitarian assistance. One of its policy documents states (SIDA 1999:1):

Programmes of development cooperation can contribute to preventing armed conflicts before they break out with the aid of targeted development projects, programmes for strengthening democracy and human rights, regional cooperation programmes and supporting communication between hostile parties.

In this article the approach is to concentrate firstly on conflict resolution as a concept – in particular the various approaches used, how they define the essence of conflict and whether democracy/development has a function anywhere in them. Next we summarise the research already done about the relationship between democracy and development. Finally, we integrate our analysis of conflict resolution into the research on democracy/development and investigate possible logical correlations between them. This study does not include an empirical investigation of possible correlations between conflict resolution and democracy/development. On the basis of these qualitative conclusions empirical studies can follow later.

2. The Essence of Conflict and Conflict Resolution

For the purpose of testing the working hypothesis, it is firstly necessary to consider how conflict and conflict resolution are understood in this discussion.

Perspectives on, and approaches towards, conflict and conflict resolution can be summarised in the following four categories or schools of thought:

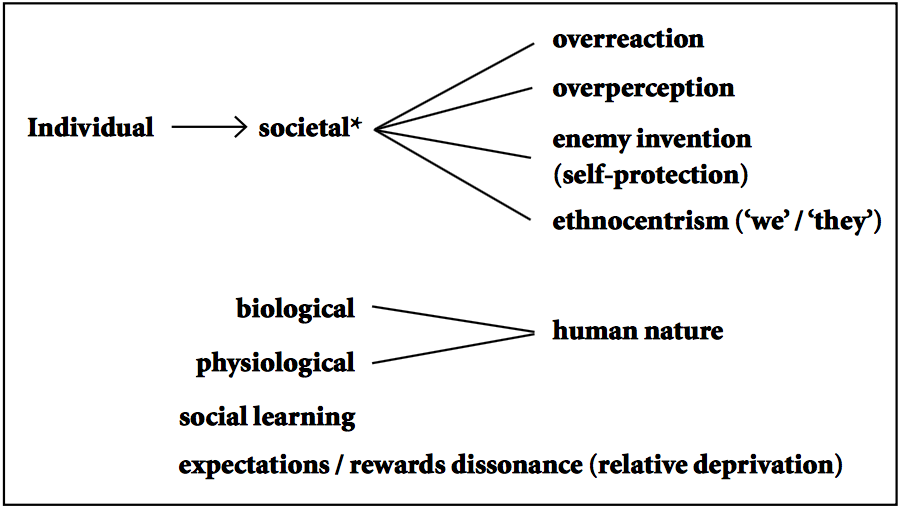

- One school of thought locates conflict at both the individual and societal/national levels. The proponents assume that at both levels the individual person is the unit of analysis. Figure 1 presents a schematic visualisation of it. Behaviour associated with conflict can be caused by, or can result in, overreaction (often because of misunderstanding, lack of communication or irrational emotionalism), overperception (negative attitudes or stereotypes, or misrepresentations), invention of an enemy (as a common external threat, to conceal internal differences, or to exploit nationalism and patriotism) or ethnocentrism (as a means to polarise a group or nation on the basis of identity or a ‘we/they’ distinction.Human nature is often described by biological or physiological conceptions. One can add to them the notion of social learning, such as processes of socialisation and cost/benefit calculations about the usage or avoidance of conflict. Another component of this school of thought is the well-known notion of dissonance between expectations and actual rewards. Ted Gurr’s construct of ‘relative deprivation’ and James C. Davies’ of a ‘J-curve’ are examples of such dissonance. All of these are perceptions, psychological constructs and individual experiences. Its logical implication is that conflict resolution should respond by changing these perceptions and addressing their causes (Sandole & Van der Merwe 1993:7-16).

- Traditionally, conflict has been treated as competition for the realisation of interests, often individual interests. Conflict resolution therefore manifested itself in the form of compromises. Power and coercion were often applied to deliver the compromises. In this context the task of a mediator was to present a compromise which the less powerful party had to accept (Burton 1987:7-8).

- During the Cold War period, conflict was not resolved but suppressed or contained. Coercion and crisis management were often used. The emphasis was therefore on short-term stability and not on longer-term sustainability (Harris & Reilly 1998:13).

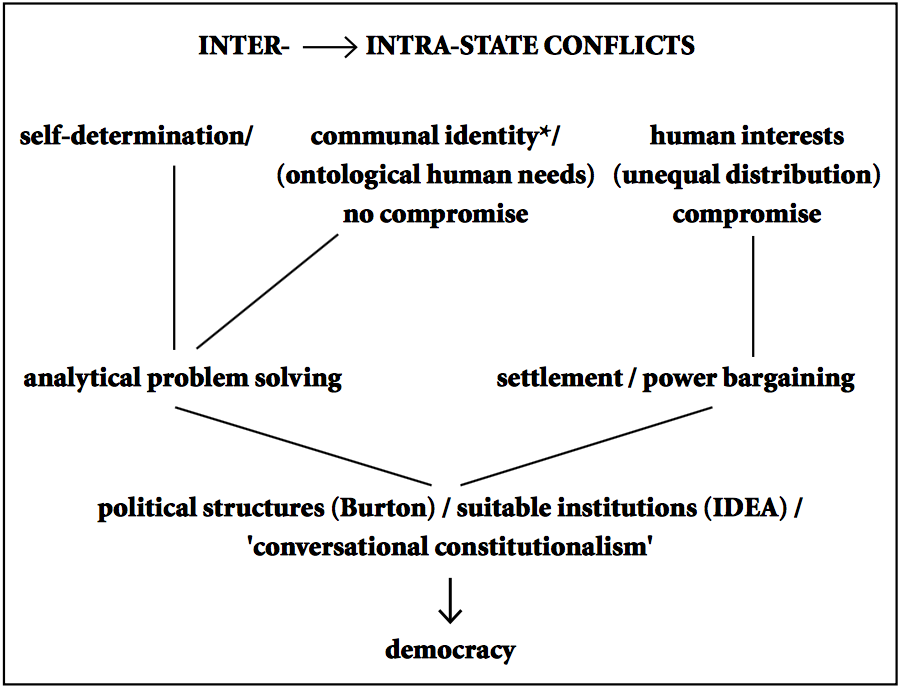

- The most contemporary school of thought concentrates on human needs and systemic (state) failure as the main causes of conflict. (It is incorporated in figure 2. See page 67.) Human needs and systemic restructuring are presented in the ambit of an institutionalist and structuralist approach. Human needs are linked here to identity needs, while systemic needs are related here to self-determination and unequal distribution of human interests. The most ontological human need, according to this view, is identity need (for example in Côte d’Ivoire, Burundi or the Sudan) (Burton 1987:16; Harris & Reilly 1998:9-10). Other human needs, described by Stephen John Stedman (in Deng & Zartman 1991:367-369,373) as basic human needs, are resource needs, dignity needs, power needs and value needs. When persons are involved in conflict, they also develop security and survival needs. These needs are exacerbated by crises in national governance or systemic failure. This is used as an explanation why intra-state conflicts have become more prevalent than inter-state conflicts. Therefore, the emphasis has also moved from solving conflictual relations between states, to resolving relations within states. Mutual agreements regarding both human needs and self-determination are zero-sum in nature and therefore no compromises can be contemplated. Instead of bargaining and searching for a settlement characterised by compromises, self-determination needs and human needs can only be addressed by analytical problem solving. Human interests, on the other hand, are not necessarily zero-sum in nature, and they can be the subject of bargaining, depending on the power relations between the competing parties. In the end both types of needs and interests have to be accommodated in one conflict resolution package. As a result of the focus on internal, systemic failure in both types of needs and interests, the emphasis in conflict resolution shifted to an institutional approach; in other words, to finding the most appropriate state institutions to resolve the failure. In this respect the International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance (IDEA) presents democracy as a normative, instrumentalist framework (Harris & Reilly 1998:16-17). As already mentioned, SIDA (1999) has a more structuralist approach, and focuses on a combination of development and political structures. (Both approaches are explained further below.) Vivian Hart (2003) developed the notion of ‘conversational constitutionalism’ in a publication for the United States Institute of Peace, which can be considered a third variation. Its emphasis is on democratic processes of constitution making as a conflict resolution approach.

At present conflict resolution appears to be accommodated within two schools of thought, namely a behavioural approach and an institutionalist/structuralist approach. These approaches can be summarised in the following two figures (see page 67).

The two approaches are not mutually exclusive, though no publications could be found in which they are integrated. The most obvious point of contact is between the societal* level in the behavioural approach in figure 1 and communal identity* in figure 2.

The preferred outcomes of the two approaches do not necessarily overlap. In the behavioural approach, conflict resolution focuses on individuals and their roles in society – especially for the purpose of establishing social harmony amongst

Fig.1: Behavioural Approach

Fig. 2: Institutionalist/Structuralist Approach

The institutionalist approach of IDEA (Harris & Reilly 1998) is less concerned about distribution matters, and concentrates on the range of options of democratic institutions available to negotiators and mediators. For them, conflict resolution is about finding the most appropriate of these institutions. Harris & Reilly (1998:16) used Angola as an illustration of this point: the 1991 Bicesse peace agreement focused on elections (i.e. a democratic practice and institution), which were to lead to a power-sharing government. Thomas Ohlson (1998:74) disputed the idea that it provided for power sharing. According to him, both parties preferred a winner-takes-all system. The Angola constitution was unsuitable for power sharing, because most of the executive powers were concentrated in a single-person President. Therefore the loser in the September 1992 presidential election, Jonas Savimbi, went back to the bush. In defiance of Savimbi, twelve Unita elected members of Parliament took up their seats. In December 1992 a government of national unity was sworn in, with Unita being allotted four of the 27 ministerial/vice-ministerial posts (Ohlson 1998:76). Conflict continued because of the zero-sum nature of the executive Presidency, and the power-sharing government as a democratic institution could not counter it.

A permutation on the institutionalist approach is Vivian Hart’s (2003) of an institutionalist (constitutionalist) approach and democratic dynamics. According to her (Hart 2003:2), constitution making ‘has become a part of many peace processes. New nations and radically new regimes, seeking the democratic credentials that are often a condition for recognition by other nations and by international political, financial, aid, and trade organizations, make writing a constitution a priority’.

Hart’s notion of ‘conversational constitutionalism’ is, however, a deviation from traditional constitution making as represented by the 1787 American Constitution. According to her, such an approach views constitution making as concluding a conflict and as a codification of a conflict settlement in order to produce permanence and stability. It constitutes therefore an act of completion, a final settlement or a social contract in which basic political definitions, principles and processes are encapsulated. In her view, such a process should not be an act of final closure, because it will entrench the post-conflict distribution of power and will exclude new participants. Her insistence on a democratic and flexible process of constitution making makes a moral claim for participation.

This combined approach appears to be tailor-made for conflict resolution, but relies too much on only one historical example, namely South Africa. Hart’s ideas are also only applicable to a relatively short transitional period. In the case of South Africa they applied to the period between the interim Constitution (1993) and finalisation of the 1996 Constitution. The process after 1996 reverted back to IDEA’s institutional approach, or democratic consolidation in the form of institution building. The 1996 Constitution closed the constitutional phase of conflict resolution, but provided an enabling framework for other processes such as affirmative action, land reform, black economic empowerment and reconciliation.

A second permutation is the structuralist approach underpinning SIDA’s approach. It ventures beyond institutions and includes changes to the social, political and economic structural or systemic configurations in a society. It entails redistributions of power, status or wealth, and new class associations. The mentioned processes of affirmative action, land reform or black economic empowerment are structuralist in approach. Insofar as they have been institutionalised, the structuralist and instrumentalist approaches complement each other.

In summary: present-day scholarship and practices in conflict resolution do not focus exclusively on democracy and socio-economic development. An important school of thought (that also includes peace education/peace studies) has a strong behavioural orientation. However, the structuralist and institutionalist approaches are endorsed (maybe even preferred) by many decision-makers. For example, Kofi Annan (in Harris & Reilly 1998:vii) wrote that more complex conflicts have ‘obliged the international community to develop new instruments of conflict resolution, many of which relate to the electoral process and, more generally, to the entrenchment of a democratic culture in war-torn societies, with a view to making peace sustainable’. A further example is the Brookings Institution’s Africa Program which set as its goal ‘to elucidate what institutions can be devised that will produce enduring peace’ (Deng & Zartman 1991:369).

The next step is to now move the focus to research conclusions regarding the relationship between democracy and development.

3. Democracy and Development

The working hypothesis assuming that socio-economic development is directly and positively correlated with democracy is examined in this section.

The hypothesis and therefore the relationship between democracy and development are often presented in terms of causality. In this respect at least three options are possible, namely:

- Taking development as the point of departure, the premise is that development is the necessary condition for a strong, high-growth economy which will be the catalyst for democratisation. Key examples in this regard are the newly industrialised Pacific Rim and possibly also China.

- On the other hand, taking democratisation as the point of departure, the premise is that it is a necessary condition for development. Examples to support this are India and some Latin American countries.

- The two projects, democratisation and development, may also be taken as running concurrently, and most of today’s developing countries are indeed expected to follow this option. One may look for example at the political and economic conditionalities of the World Bank and IMF.

What is development? According to Przeworski and others, it is about structural transformation, and changes in values and ethical approaches (such as nepotism or corruption). Furthermore, development articulated as increase in growth, is operationalised as increase in income, productivity, consumption, investment, education, life expectancy, employment, childbirth survival and similar indicators (Przeworski et al 2000:1,3).

In the current international climate, development is viewed through the prism of ‘modernisation’, with the main emphasis on growth and its ‘trickle-down’ effect to the society at large. It predicts a social structure which is more complex. The paradigm also predicts that newly mobilised groups (who will emerge partly as a result of higher growth and concomitant, improved socio-economic development) will rise against the incumbent undemocratic regime. At the same time development depoliticises certain spheres of society, and frees politics from too many demands and expectations. For example, politics is not anymore the main instrument for social and economic upward mobility. Development is associated with differentiation and specialisation and thereby spheres of competition in societies are multiplied and diversified. Another variation of modernisation can be attributed to the newly industrialised countries (NICs) in the Pacific Rim: high growth (i.e. development) which depends on a ‘benevolent autocracy’. They made a strong case for a general belief that democracy’s freedoms and rights are incompatible with high economic growth. Hence, development and democracy are not necessarily causal in their relationship. From another point of view but with the same implication, Turkey serves as a noteworthy case. It developed a huge economy but the population exhibits all the symptoms of development with marked disparities in respect of almost all the main development indicators. As an aspirant EU member since 1999, Turkey has to satisfy the Copenhagen criteria, which includes political and economic liberalisation. Hence, since 2002 the Turkish government has adopted radical changes which can only be described as a new ‘wave’ of democratisation. The Turkish Daily News (9 May 2005) reported the following about how these political and economic changes affect economic growth:

Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdoˇgan conceded that the layman had yet to reap the fruits of economic growth and other positive developments, but he said time was needed to[o] for economic reforms to be digested.

Seymour Martin Lipset can arguably claim credit for introducing in 1959 the debate about a probable relationship between the degree of economic development and the prevalence of a democratic regime in a country. He concluded that a strong, positive relationship between the two variables exists (Przeworski et al 2000:78-79), but he did not conclude anything about a correlation of causality between them. Adam Przeworski and others tested those conclusions and produced the following results:

- As a variable with an impact on democratic regimes, economic development is more important than the regime’s political legacy, religious or ethnolinguistic fractionalisation (diversity) or the impact of the international political environment. But an important qualification is that economic development is not directly and positively correlated to democracy: democratic transitions are less likely in both poor and rich countries, and more likely in intermediate-income societies (Przeworski et al 2000:92). (It can therefore be presumed that democratisation is unlikely in the absence of some degree of pre-existing development.)

- With regard to growth as a factor, Przeworski, on the one hand, concluded that regime types do not affect the growth rate (Przeworski et al 2000:160). Democracy, therefore, does not produce higher growth rates than other regime types. Freedom House, on the other hand, surveyed GDP growth rates (in the period 1990-98) and linked them to their assessment and ratings of the levels of freedom in the states. Their conclusion is that in developed states the highest growth rates prevalent are in partly free (not totally free) societies. In developing states there is a direct, positive correlation between growth and freedom (Freedom House). Therefore, in totally free developing societies growth can be higher than in unfree societies, while in developed states it is optimal in partly free societies. For Freedom House, regime types are therefore relevant.

- In related research but with a slightly different focus, Quinn & Woolley (2001:653) concluded that economic policies in democracies tend to be risk-avoiding or avoiding volatility. High growth is associated with volatility, and hence democracies will also avoid high economic growth.

- Regarding per capita income, Przeworski concluded, firstly, that a strong positive correlation is present between the level of per capita income and the degree of democratic stability/survival. However, wealthy countries are less sensitive to a decline in income than poor countries. (A similar positive correlation exists between education and democratic survival.) A decline, therefore, in personal income in developing states is related to a high probability of democratic decline. A decline in income is not a threat to non-democratic regimes, however (Przeworski et al 2000:101,109). The level of growth and changes in income are therefore sensitive variables, though Quinn & Woolley showed that economic volatility is even more sensitive.

- Another aspect related to growth, is that democracy is more stable in egalitarian societies than in those with high levels of income inequality. Non-democratic regimes are, once again, not affected by it, and their regime stability is not influenced by income inequality. Moene & Wallerstein (2001:23-25) concluded that income distribution of most egalitarian societies is characterised by relatively higher spending on income replacement (i.e. unemployment insurance, sickness pay, occupational illness, disability, etc.) than on other forms of social security. Public expenditure on pensions, health care, family benefits and housing does not have the same impact on egalitarianism as income replacement. We can therefore conclude that democracy is more stable in states with relatively high levels of public spending on income replacement. It can also be inferred that in developing democracies high priority should be placed on secure income in the form of job creation and employment security.

From the above-mentioned research results the following conclusions are possible:

- High growth (associated with high volatility) and loss of personal income (or insufficient income replacement) are potential threats to democratic consoli dation and stability. According to Freedom House, high growth rates are more likely in, and compatible with, both developed and partly free (but not fully free or fully democratic) states as well as developing and free (fully democratic) states. For Przeworski et al democratic transitions are more prevalent in intermediate-income societies. Growth, for them, is not determined by the regime type. Developing but poor states with a low growth-rate are therefore unlikely to democratise or increase their growth rates.Democratisation and consolidation are hence optimal in conditions of intermediate growth and income, combined with sufficient income replacement.

- The more egalitarian income distribution is, the more likely is democratic stability. It is partly associated with spending on income replacement. It means that states with intermediate-income levels and with egalitarian income structures have a good chance to succeed with democratisation and democratic survival. It suggests an optimal situation in which intermediate levels of growth are present, but growth that does not widen the income gap and that does not result in loss of, or threat to income.

In view of the above conclusions, ‘small N’ samples of case studies in Africa have been selected to test the conclusions in conditions specifically characterised by conflict. Thereby their relevance for conflict resolution can be investigated.

3.1 African case studies: Growth

Fig. 3: Per Capita GNP (Average Annual Growth Rate, and Ranking)

| Case | 1980-92 | Ranking | 1985-95 | Ranking | 1988-99 | Ranking |

| South Africa | 0,1% | 89 | -1,1% | 91 | -0,9% | 108 |

| Mozambique | -3,6% | 1 | 3,6% | 1 | 6,6% | 2 |

| Angola | n/a | – | -6,1% | 33 | -37,4% | 1 |

Sources: World Development Report 1994:162-163, World Development Report 1997:214-215, World Development Report 2000/2001:274-275.

The correlation between growth and democratisation is the first to be tested by three southern African case studies. Both South Africa and Mozambique conducted democratisation elections in 1994 after prolonged periods of conflict. Angola concluded a peace agreement (Bicesse) in 1991 and held a multiparty election the next year. However, the disputed outcome of the Angolan presidential election introduced a new wave of civil war that only came to an end in 2002. Angola, with its extended period of conflict and lack of national consensus on democracy, therefore serves as a control case for the other two cases of relatively peaceful democratisation. Their growth rates in terms of per capita GNP and their GNP ranking in the world (1 = lowest GNP in the world) are summarised as follows:

The figure shows that in the case of South Africa during its period of undemocratic rule it had the 89th lowest per capita GNP in the World Bank database. It improved by two places in the period 1985-95, which included the new, interim Constitution (1993) and the 1994 general election. It improved even more (by 17 places) in 1998-99. Mozambique, on the other hand, was the poorest country during its undemocratic period. It improved one place in the five years after its 1994 general election (compared to South Africa’s 17 places). Both states experienced relatively successful introductions of multiparty elections and general democratisation. Both have experienced improvements in growth rates since 1994 though the levels of growth differ markedly: in South Africa it was an increase of 0,2% and in Mozambique of 3,0%. Mozambique’s real growth rate of 6,6% is high in terms of international standards: the 5th highest after Moldova, Turkmenistan, South Korea and Ireland (World Development Report 2000/2001:274-275). The research results, therefore, are expected to suggest that Mozambique will experience problems with economic volatility, and therefore with democratic stability, while the situation is the opposite. The fact that its high growth has not yet produced a significant overall change in its economy (i.e. it improved by only one position in the world rankings) is a possible explanation for the absence of democratic instability. Compared with South Africa’s improvement of seventeen places based on a growth increase of only 0,2%, it suggests that research should not only look at real per capita GNP growth as an indicator of possible economic volatility, but also at the growth rate in relation to the economy’s level of development. It is suggested here for further research that a high growth rate (and high volatility) in relatively low GNP societies might not threaten democratic survival as much as the same growth rate in intermediate- and high-GNP societies.

Both South Africa and Mozambique experienced increases in growth between 1995 and 1998. Therefore, the general research conclusions that a decline is a threat to democratic survival, cannot be tested here. Angola, on the other hand, continued with undemocratic and violent conditions, which have had devastating effects on its growth rate. Since the middle of 2002 a new peace is emerging and a new constitution is also in the pipeline but it is still too early to use it as a new case study.

3.2 African case studies: Income distribution

Moene & Wallerstein’s (2001) research results concluded that the more egalitarian a society’s income distribution is, the more likely is its democratic durability. In order to test it, we can look at a few cases in Africa, and use India (an important developing and democratic state) and Switzerland (as a democratic country with the highest per capita GNP in the world) as control cases. To the right follows a table with the income or consumption patterns of select African states (see page 77). Due to incomplete data, it is impossible to do comparisons for similar annual statistics, though the majority of data represent the early- and middle-1990s at the time of widespread ‘third wave’ democratisation. Therefore, instead of presenting the data as chronologically comparable, it can only be used to search for possible trends. For example, first multiparty elections were held at different points in time in: Kenya (1991), Zambia (1991), South Africa (1994) and Mozambique (1994). Linking comparable time differences between the elections and the annual statistics might shed light on the relevance of income distribution for economic development.

From this figure it appears that the median distribution of the African states is 6% / 11% / 15% / 22% / 46%. The countries closest to it are Morocco, Algeria, Tanzania, Uganda, Mozambique, and Ghana to a lesser extent. Switzerland follows the same pattern, and India in 1997 was not far from it. The countries that deviate substantially from it are Rwanda in 1983-85 before the genocide (the most egalitarian example listed here), Kenya, Zambia and South Africa. The latter is the most unequal of them all, followed by Kenya (1992). After Rwanda, Ghana appears to be the second most egalitarian example – almost identical to India.

Tendencies in the democratising states are the following: in Kenya income/consumption distribution improved most dramatically of all the cases; in Zambia it is a mixed tendency; in Ghana it remained relatively unchanged; and in South Africa the situation worsened slightly, though the time difference between the two sets of data is in the latter case too short for a conclusive result.

Fig. 4: Distribution of Income or Consumption Distribution between the quintiles in the populations

| State | Period | lowest 20% | 21-40% | 41-60% | 61-80% | highest 20% |

| Morocco | 1990-91 | 6,6 | 10,5 | 15,0 | 21,7 | 46,3 |

| 1998-99 | 6,5 | 10,6 | 14,8 | 21,3 | 46,6 | |

| Algeria | 1988 | 6,9 | 11,0 | 15,1 | 20,9 | 46,1 |

| 1995 | 7,0 | 11,6 | 16,1 | 22,7 | 42,6 | |

| Tanzania | 1993 | 6,9 | 10,9 | 15,3 | 21,5 | 45,4 |

| Uganda | 1992-93 | 6,8 | 10,3 | 14,4 | 20,4 | 48,1 |

| Rwanda | 1983-85 | 9,7 | 13,2 | 16,5 | 21,6 | 39,1 |

| Kenya | 1992 | 3,4 | 6,7 | 10,7 | 17,0 | 62,1 |

| 1994 | 5,0 | 9,7 | 14,2 | 20,9 | 50,2 | |

| South Africa | 1993 | 3,3 | 5,8 | 9,8 | 17,7 | 63,3 |

| 1993-94 | 2,9 | 5,5 | 9,2 | 17,7 | 64,8 | |

| Mozambique | 1996-97 | 6,5 | 10,8 | 15,1 | 21,1 | 46,5 |

| Zambia | 1993 | 3,9 | 8,0 | 13,8 | 23,8 | 50,4 |

| 1996 | 4,2 | 8,2 | 12,8 | 20,1 | 54,8 | |

| Ghana | 1992 | 7,9 | 12,0 | 16,1 | 21,8 | 42,2 |

| 1997 | 8,4 | 12,2 | 15,8 | 21,9 | 41,7 | |

| CONTROL | ||||||

| India | 1992 | 8,5 | 12,1 | 15,8 | 21,1 | 42,6 |

| 1992 | 8,5 | 12,1 | 15,8 | 21,1 | 42,6 | |

| 1997 | 8,1 | 11,6 | 15,0 | 19,3 | 46,1 | |

| Switzerland | 1982 | 5,2 | 11,7 | 16,4 | 22,1 | 44,6 |

| 1992 | 6,9 | 12,7 | 17,3 | 22,9 | 40,3 | |

Sources: World Development Report 1997:222-223, World Development Report 2000/2001:282-283

In the non-democratic states the tendencies are that in Morocco it remained unchanged and in Algeria it improved slightly.

Conclusions about discernible tendencies are almost impossible, except to say that consistent patterns are not visible. In 1983-85 Rwanda was the most egalitarian case, though not democratic. However, it could not prevent the genocide in 1994. Ghana is the second most egalitarian example. Since adopting a new constitution and the presidential elections in 1992, it experienced relative democratic durability. On the other hand, in South Africa as the most unequal case (which will probably deteriorate even more), durability of democracy has not been threatened for more than ten years.

In Zambia, where between 1991 and 2001 a multiparty system was established but electoral manipulation has been rampant, the tendency is mixed: the proportion of the low- and high-income groups increased, while the middle shrunk. In Kenya, following more or less the same political pattern, the income distribution improved quite dramatically after the first multiparty election.

The tendency towards equal distribution in Algeria showed an improvement, though it was engaged in a civil war since the aborted election in 1991. In Morocco, however, with exactly the same income distribution as Algeria’s, and also engaged in conflict with Western Sahara since the 1970s, there is an unchanged distribution pattern.

How egalitarian is the pattern in Africa? In comparison with the most egalitarian societies in the world (the Slovak Republic the most egalitarian, Belarus 2nd most, followed by Austria, Japan, Finland and Norway) the medians are the following (computed from World Development Report 2000/2001:282-283):

Fig. 5: Comparison of Distribution of Income or Consumption Distribution between the quintiles in the populations

| lowest 20% | 21-40% | 41-60% | 61-80% | highest 20% | |

| Median (Africa) | 6% | 11% | 15% | 22% | 46% |

| Median (top six, world) | 10 | 14 | 18 | 22 | 36 |

| Slovakia (top – world) | 11,9 | 15,8 | 18,8 | 22,2 | 31,4 |

| Rwanda (top – Africa) | 9,7 | 13,2 | 16,5 | 21,6 | 39,1 |

The starkest disparities between Africa and the rest of the world are in the categories of quintiles with the lowest 20% and the highest 20% of the populations. It means that in the top 20% of the populations in Africa about 10% more wealth is concentrated than in that segment in the other societies. Income/consumption in the lowest 20% is about five percent less than in the other societies. (It is notable that the two most egalitarian societies – the Slovak Republic and Belarus – were part of the Eastern bloc, and therefore are relatively new democracies. It enhances the validity of comparisons made between the medians in Africa and the rest of the world.)

All the African cases of democracies used here are relatively young. None of them have regressed into a non-democratic regime. Data from troubled states like Côte d’Ivoire, Sierra Leone and the Central African Republic were not available to test the research results against them.

So far we have treated development and growth as the independent variables and democratic durability as the dependent variable. In the next section we turn it around, to democracy as the independent variable and conflict resolution as the dependent variable.

3.3 African case studies: Human development index

An important indicator of the degree of development is quality of life as expressed by the human development index (HDI). From the working hypothesis it can be derived that development would improve the quality of life (operationalised as HDI), which in turn will prevent future conflicts caused by socio-economic disparities. Alternatively, it expects that under conditions of democracy and development, the HDI in a state will increase.

The following case studies have been selected from the United Nations Development Program’s 2003 database to test it (see Figure 6 on page 80).

Fig. 6: Comparison of Human Development Indices

| HDI World Ranking (2001) | African State | 1975 | 1980 | 1985 | 1990 | 1995 | 2001 |

| 107 | Algeria | 0,510 | 0,559 | 0,609 | 0,648 | 0,668 | 0,704 |

| 111 | South Africa | 0,660 | 0,676 | 0,702 | 0,734 | 0,741 | 0,684 |

| 125 | Botswana | 0,509 | 0,573 | 0,626 | 0,674 | 0,666 | 0,614 |

| 129 | Ghana | 0,444 | 0,474 | 0,487 | 0,515 | 0,537 | 0,567 |

| 133 | Swaziland | 0,510 | 0,541 | 0,567 | 0,611 | 0,606 | 0,547 |

| 138 | Sudan | 0,351 | 0,378 | 0,399 | 0,431 | 0,465 | 0,503 |

| 145 | Zimbabwe | 0,544 | 0,570 | 0,626 | 0,614 | 0,567 | 0,496 |

| 146 | Kenya | 0,440 | 0,487 | 0,510 | 0,535 | 0,519 | 0,489 |

| 147 | Uganda | – | – | 0,402 | 0,403 | 0,412 | 0,489 |

| 158 | Rwanda | 0,349 | 0,394 | 0,405 | 0,359 | 0,343 | 0,422 |

| 164 | Angola | – | – | – | – | – | 0,377 |

| 167 | DRC | 0,419 | 0,426 | 0,429 | 0,417 | 0,380 | 0,363 |

| 170 | Mozambique | – | 0,309 | 0,295 | 0,317 | 0,325 | 0,356 |

Source: UNDP 2003:243-244

Mozambique and South Africa launched their democratisation in 1994. The HDI of South Africa decreased between 1995 and 2001, while that of Mozambique increased. The HDI of Botswana – one of the oldest democracies in Africa – decreased since 1990. South Africa and Botswana therefore falsify a positive correlation between democracy and increased HDIs. States characterised by relatively peaceful but undemocratic practices – like Swaziland, Kenya and Zimbabwe – all shared decreases in their HDIs. On the other hand, between 1975 and 1995 South Africa under apartheid experienced sustained increases. States in the midst of internal physical conflicts or soon after conflicts – Algeria, the Sudan, Rwanda and the DRC – revealed a contradictory tendency: most of their HDIs have increased, except for the DRC’s. Two models of IMF-directed development in Africa – Ghana and Uganda – confirm the expected tendency of increased HDIs, but they are far behind Algeria in relative terms, which is destabilised by a debilitating civil war. Except for the Seychelles (ranking 36), Libya (ranking 61), Mauritius (ranking 62) and Tunisia (ranking 91), Algeria is the highest African state on the index despite its internal conflict. Macedonia (ranking 60) – a conflict-ridden Balkan state – is higher on the index than most relatively peaceful African states.

HDI is a composite indicator of life expectancy at birth, education, per capita GDP and other development indices. From the above it appears that the HDI indices make it impossible to conclude a specific correlation between development and conflict. Neither is it possible to detect a correlation between HDI and democracy, especially in the cases plagued by conflict.

The overall conclusion about the relationship between democracy and development as informed by the African case studies is that they do not in all respects confirm the general research results. The case studies are, however, too limited in scope as a basis for theoretical amendments, but at least they suggest more subtle qualifications of the research results.

4. Instrumentalist versus Intrinsic Nature of Democracy

The second important part of this article is about the relationship between democracy and development on the one hand, and conflict resolution on the other hand. Can democracy and development, therefore, constitute a blueprint for conflict resolution – especially in view of the institutionalist or structuralist approach?

In order to understand how democracy and/or economic development can be part of a programme of conflict resolution, it is firstly necessary to determine how people perceive democracy. If they understand it as dependent on development, then the research conclusions in the previous section become relevant for a conflict resolution design. If they understand democracy as separate from development, only the relationship between the political (and not economic) dimensions of democracy and conflict resolution is relevant.

The next step is therefore to look at people’s perceptions of, and attitudes towards, democracy. Broadly speaking, two variations have been identified (Huntington 1991:5-9):

- The intrinsic or procedural perspective, in which democracy is valued as an end in itself, and people value its political freedoms and rights. Democratisation therefore entails agreement on, and implementation of, political institutions and procedures that encapsulate democratic values like participation, accountability, equality and freedom.

- The instrumentalist or substantive perspective, according to which democracy is valued as a means towards other ends, mostly as an instrument to alleviate socio-economic conditions and promote equality. For democracy to be consolidated, it needs to be seen as producing positive socio-economic results. Socio-economic equality is therefore treated as either an integral characteristic of democracy or as one of the most important criteria for assessing democratic performance. The durability of democracy is therefore correlated to socio-economic equality and egalitarianism.The intrinsic perspective can be sustained even under conditions of an economic downturn or social upheaval. On the other hand, support for democracy from an instrumentalist perspective is conditional upon acceptable economic and government performance. These perceptions are also followed in academic scholarship: Jon Elster and Claude Ake are examples of those who subscribe to an instrumentalist view; Adam Przeworski and Larry Diamond, for example, subscribe to the intrinsic view.

The relevance of these two perspectives for conflict resolution is the following. Should the argument be followed that conflict can be resolved by changes to the political and/or economic structure of a society and that democracy is the regime form most preferred for securing such changes on a sustainable basis, it implies that the citizens have to have an instrumentalist perspective of democracy. In other words, the people should expect democracy to produce outcomes in areas other than ‘pure’ politics, such as improved socio-economic conditions, and thereby remove the socio-economic and related causes of conflict. Should an intrinsic perspective be the dominant view of the people affected by a conflict, democracy will be a conflict resolution instrument only if the conflict was exclusively about a minimalist notion of democracy, such as about providing human rights, or about democratising elections. As an example of this view, George Ngwane (1996:13) argues that ‘one way therefore that African countries have been handling Intrastate conflict is through the call for constitutional talks which are sovereign or the creation of Transitional Governments especially when there are controversies on electoral processes’. Przeworski’s empirical research conclusions support his minimalist or intrinsic view of democracy (Przeworski et al 2000:15), which suggests a limited utility value for democracy in conflict resolution.

In order to test these views further in the African context, the following research results can be summarised:

Bratton & Mattes (2001) reported on surveys about democracy perspectives in Zambia (1993, 1994), Ghana (1999) and South Africa (1995). For Zambians the essence of democracy is competitive elections and their electoral freedom of choice. Ghanaians concentrate on civil liberties and personal freedoms as the essence of democracy. South Africans, on the other hand, used a more materialistic view and focused on equal access to houses, jobs and decent income. The authors’ general conclusions are that Africans are more inclined to use an intrinsic perspective (like emphasising individual liberties, political rights) than an instrumentalist view (South Africa is an exception). They qualify their conclusion by saying that Africans tend to include a combination of both elements in their perspectives, but that the balance between them differs across countries. Preferences for political goods within the intrinsic view differ also: in Zambia it is for elections; in Ghana it is for freedom of speech (Bratton & Mattes 2001:448-455).

The relevance of these conclusions for conflict resolution is that perceptions of democracy are determined by contingent factors and cannot be generalised about. The utility value of democracy for conflict resolution can therefore be determined only after knowing what people’s opinions about democracy are in terms of the intrinsic/instrumentalist choice. It, therefore, does not support IDEA’s unqualified advocacy of democracy. Conclusions about SIDA’s advocacy of a structuralist approach which includes development, are more difficult to make, because we have not investigated in this article the impact of development in the absence of democracy, on conflict resolution. This conclusion about democracy’s utility value only partly supports Przeworski’s results, because he totally excludes an instrumentalist view from his concept of democracy.

The investigation can be taken one step further by testing the counter situation, namely in which a democracy and relative peace already exist, but a gradual decline in popular trust is experienced. Is it correct to expect that such a situation is prone to conflict? In other words, that once democracy’s instrumentalist utility value declines (but not necessarily its intrinsic value), it creates opportunities for conflict? Does it mean that a consolidated democracy is a guarantee for conflict prevention?

Robert Mattes et al. (2000) did a survey on views about democracy amongst South Africans approximately five years after the 1994 elections, and compared them with the rest of Southern Africa. Their conclusions were the following:

- South Africans’ assessments of their political institutions and leaders are becoming increasingly pessimistic;

- South Africans are less interested in, and participate less in democratic politics, than their neighbours;

- South Africans have the greatest awareness of the concept of democracy in Southern Africa; they have a largely positive understanding of the concept; the average South African rejects all the non-democratic alternatives, but with less frequency and strength of opinion than in the rest of the region;

- South Africans are less supportive of, and committed to, democracy than their regional neighbours.

Opinions about the South African political system are summarised as follows:

- No widespread sense of legitimacy for the political institutions has yet emerged;

- Elected institutions enjoy less popular trust than purely state institutions; and

- Satisfaction with governmental performance has decreased (Mattes et al 2000:ii-iv).

These research conclusions indicate that South Africa’s democracy has not yet reached the stage of consolidation (‘the only game in town’). Assessments of elected representatives, their institutions and government are increasingly negative. However, support for the concept of democracy and its pure institutions (i.e. an intrinsic perspective) is more sustained. Given the fact that a materialist/instrumentalist view is most prevalent in South Africa, one could anticipate less support for democracy, and more passive than active support.

In respect of conflict (crime excluded), no substantial increases appeared in South Africa in 1994-2000. On the basis of one case, South Africa, it is unscientific to reach a general conclusion and induce it into a theoretical construction. But without including other variables and case observations, a single case can, however, falsify a hypothesis about direct causality between a decline in democratic trust and conflict. Therefore, it is possible to conclude that even in a predominantly instrumentalist environment like South Africa’s, the absence of conflict does not depend solely or mainly on a consolidated democracy.

Conclusion

In this article a triangulation of democratisation, economic development and conflict resolution/prevention has been the focus of attention. This was motivated by the increasingly popular notion applied in conflict situations like Sudan, Iraq, Afghanistan and the DRC, that democracy and development are mutually supportive national imperatives and moral objectives, and/or that a combination of democratisation and economic development is the most preferred blueprint (in the name of post-conflict reconstruction) for conflict resolution and prevention of conflicts in future. Three working hypotheses were derived from these notions.

The first hypothesis is that democratisation (including good governance) is directly and positively correlated with conflict resolution/-prevention. The conclusion in this regard is that democracy is not a generic concept and depends on varying public perceptions. The differences between instrumentalist and procedural approaches (and accompanying perceptions) to democracy have been discussed above. The root causes of a conflict have to be aligned to the particular understanding of democracy in any given environment. If the root causes are about political discrimination, the absence of a social contract or human rights violations, while the dominant understanding of democracy is procedural in nature, then a positive and direct correlation between democratisation and conflict resolution is highly likely. If the root cause is about identity matters like religion or origin (for example, about the content of Ivoirité in Côte d’Ivoire) and democracy is predominantly substantive in content, then democracy is less likely to be the most appropriate instrument for resolving the conflict. It is therefore appropriate to conclude that the first hypothesis is determined by a contingent relationship. This conclusion is not directly applicable to the ‘democratic peace’ notion: the claim that democratic states do not engage in conflict with one another. ‘Democratic peace’ is more relevant for maintaining peace by diplomatic means than for peace making. Therefore, that debate does not form part of this article.

The second hypothesis is that socio-economic development is directly and positively related with democracy. This hypothesis relies largely on the research done by a wide range of scholars, notably Przeworski and his colleagues. Their research concluded that democratic regimes are more sensitive to economic development than to the impact of their political legacy, religious or ethnolinguistic diversity or the international political environment. Economic growth in developing states is also directly and positively correlated to freedom. Per capita income is strongly correlated to the degree of democratic stability, and a decline in income in developing states increases the probability of democratic decline. A select number of African case studies were used to test these conclusions. Regarding growth as a variable, all the case studies do not support a positive correlation with real per capita GNP growth, but suggest that the growth rate in relation to the economy’s level of overall development be taken into account. Relatively low real growth but with major, visible impact on the economy, can cause more volatility and democratic instability than high growth with little social impact. Changes in income distribution associated with economic growth and egalitarianism do not register any discernible impact on democratic stability, thereby deviating from Moene & Wallerstein’s research conclusions. The human development index as an indicator of quality of life is another variable with no consistent correlation with democratic stability. Hence, the African examples question the validity of a theoretical correlation between democracy and economic development.

The overall conclusion is that the durability of democratic regimes is more sensitive to changes in the indicators of development (like growth, volatility or income distribution) than the durability of non-democratic regimes. Economic development factors are also not a catalyst for democratisation.

The third hypothesis is that democratisation and socio-economic development provide a necessary structural basis for resolving deep-rooted conflicts or for preventing conflicts. Conclusions regarding the second hypothesis question a consistent correlation between democracy and development. Therefore, their mutually supportive function as a tool to resolve conflict is inherently questionable. If one adds the problems raised with the first hypo thesis, the only option left is whether economic development on its own (under undemocratic conditions) can resolve conflict. It has not been investigated in this article. Two examples of applying this option were the attempts at socio-economic development in selected South African townships (notably Alexandra) in the 1980s, and as an element of the British anti-guerrilla strategy in Malaysia. The former failed and the latter succeeded.

All of the above suggest that neither democratisation nor economic development, nor a combination of them, as instruments of structural social change, can be applied under all circumstances for conflict resolution. Sometimes they can be counterproductive and actually enhance a situation’s conflict potential.

Sources

- Bratton, Michael & Mattes, Robert 2001. Support for democracy in Africa: intrinsic or instrumental? British Journal of Political Science. Vol.31 part 3 (July).

- Brown, Michael E., Lynn-Jones, Sean M. & Miller, Steven E. (eds.) 1996. Debating the Democratic Peace. Cambridge, Mass: The MIT Press.

- Burton, John W. 1987. Resolving deep-rooted conflict: a handbook. Lanham et al.: University Press of America

- Chernoff, Fred 2004. The study of democratic peace and progress in International Relations. International Studies Review. Vol. 6 No.1 (March).

- Deng, Francis M. & Zartman, I. William (eds.) 1991. Conflict Resolution in Africa. Washington, DC: Brookings Institution.

- Elman, Miriam Fendias 1999. The never-ending story: democracy and peace. International Studies Review. Vol. 1 No.3 (Fall).

- Freedom House (http://freedomhouse.org).

- Fukuyama, Francis 1989. The end of history? The National Interest. No.16 (Summer).

- Harris, Peter & Reilly, Ben (eds.) 1998. Democracy and Deep-rooted Conflict: Options for Negotiators. Stockholm: IDEA.

- Hart, Vivian 2003. Democratic Constitution Making. Report no. 107. Washington, DC: United States Institute of Peace (http://www.usip.org/pubs/specialreports/sr107.html).

- Huntington, Samuel P. 1991. The Third Wave: Democratization in the Late Twentieth Century. Norman & London: University of Oklahoma Press.

- Iheduru, Obioma M. 1999. The Politics of Economic Restructuring and Democracy in Africa. Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press.

- Landa, Dimitri & Kapstein, Ethan B. 2001. Inequality, growth, and democracy. (Review article). World Politics. 53(2) (January).

- Mattes, Robert, Davids, Yul Derek & Africa, Cherrel. 2000. Views of Democracy in South Africa and the Region: Trends and Comparisons. The Afrobarometer series, No.2. Rondebosch: IDASA for the Southern African Democracy Barometer.

- Moene, Karl Ove & Wallerstein, Michael 2001. Insurance or redistribution: The impact of income inequality on political support for welfare spending. (Mimeo.).

- Ngwane, George 1996. Settling Disputes in Africa: Traditional Bases for Conflict Resolution. Yaoundé: Buma Kor.

- Ohlson, Thomas 1998. Power Politics and Peace Politics: Intra-state Conflict Resolution in Southern Africa. Uppsala: Department of Peace and Conflict Research, Uppsala University.

- Przeworski, Adam 1991. Democracy and the Market: Political and Economic Reforms in Eastern Europe and Latin America. Cambridge et al.: Cambridge University Press.

- Przeworski, Adam & Limongi, Fernando 1993. Political regimes and economic growth. Journal of Economic Perspectives. 7(3) (summer).

- Przeworski, Adam, Alvarez, Michael E., Cheibub, José Antonio & Limongi, Fernando 2000. Democracy and Development: Political Institutions and Well-being in the World, 1950-1990. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Quinn, Dennis P. & Woolley, John T. 2001. Democracy and national economic performance: the preference for stability. American Journal of Political Science. 45(3) (July).

- Reychler, Luc. 1999. Democratic Peace-building and Conflict Prevention: The Devil is in the Transition. Leuven: Leuven University Press.

- Sandole, Dennis J.D. & Van der Merwe, Hugo (eds.) 1993. Conflict Resolution Theory and Practice: Integration and Application. Manchester & New York: Manchester University Press.

- SIDA 1999. Strategy for conflict management and peace-building. Stockholm: SIDA (Division for Humanitarian Assistance).

- Turkish Daily News (”PM Erdoˇgan says it takes time for economy to digest reforms’), 9 May 2005 (http://www.turkishdailynews.com.tr/article.php?enewsid=12806).

- UNDP 2003. Human Development Report 2003 (http://www.undp.org/hdr2003/pdf/hdr03_HDI.pdf).

- World Bank Group. Conflict Prevention and Reconstruction. Poverty Reduction Strategy Papers. (http://www.worldbank.org/ESSD/sdvext.hsf/67ByDocName/ConflictAnalysisPovertyReductionStrategyPapersPRSPinconflict-affectedcountries).

- World Development Report 1994. Infrastructure for Development. New York: Oxford University Press for the World Bank.

- World Development Report 1997. The State in a Changing World. New York: Oxford University Press for the World Bank.

- World Development Report 2000/2001. Attacking Poverty. New York: Oxford University Press for the World Bank.