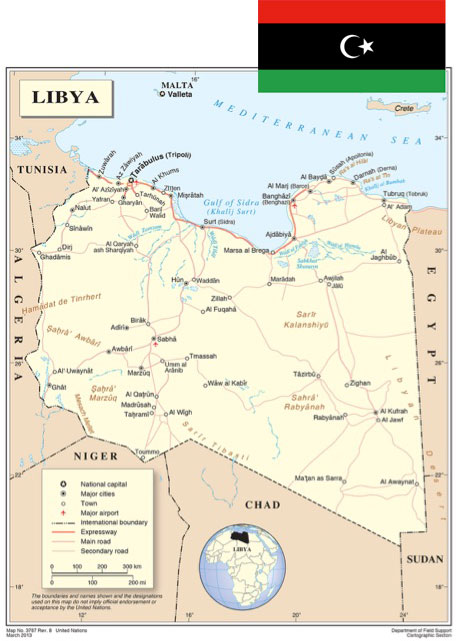

Popular uprisings in North Africa and the Middle East, referred to as the ‘Arab Spring’ and which started in Tunisia, led to the collapse of the age-old authoritarian regimes of the Arab world. The Tunisian uprising had a domino effect as it spread to Egypt and later to Libya, which had been under a 41-year dictatorial rule.1 The revolt spread rapidly throughout Libya, and the insurgents made swift progress. Unlike the other fallen leaders, Colonel Muammar Gaddafi declared his determination to stay in power and waged war against the rebels, thus throwing the country into a civil war. A spike in human rights violations saw the United Nations Security Council (UNSC) pass Resolution 1970 on 26 February 2011, and 19 days later Resolution 1973 was passed, imposing a no-fly zone and an arms embargo on Libya. Under its Chapter VII powers, the Security Council demanded an immediate ceasefire; an end to violence and all attacks against civilians; and called for member states to “take all necessary measures” to prevent further civilian casualties and enforce compliance with the resolution. The implementation of this resolution was problematic, as it not only led to the murder of Gaddafi but also many Libyans, who lost their lives in the airstrikes carried out by the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) forces and later threw Libya into a precarious situation, due to lack of follow-up.

The African Union (AU) did not remain silent in the wake of the uprisings. Despite the fact that events unfolded quickly from Tunisia to Egypt and then Libya, and considering that these types of events were not in mind when the 2000 Lomé Declaration on Unconstitutional Changes of Government was being drafted, the AU was quite dynamic during the crisis:2

- On 23 February 2011, the AU Peace and Security Council strongly condemned the “indiscriminate and excessive use of force and lethal weapons against peaceful protesters, in violation of human rights and international humanitarian law”. It further called the aspirations of the Libyan people for democracy as “legitimate”.

- On 10 March 2011, an AU High-level Ad Hoc Committee on Libya was established by the Peace and Security Council, tasked to find means to stop the escalation of the Libyan The committee was mandated to pay special attention to the troubled state, with a view to engaging all key stakeholders in the quest to mediate a solution to the crisis. Working with the AU Commission chairperson Jean Ping, five countries represented by their respective presidents were appointed to this ad hoc committee: South Africa (Jacob Zuma), Mauritania (Mohamed Ould Abdel Aziz), Mali (then under Amadou Toumani Toure), Congo-Brazzaville (Denis Sassou Nguesso) and Uganda (Yoweri Museveni). The committee developed an AU roadmap to peace, which sought to bring all the stakeholders to the table for purposes of working out modalities to implement a five-point plan. The objectives of this plan were: protection of civilians and the cessation of hostilities; provision of humanitarian assistance to affected populations; the initiation of political dialogue among Libyan parties to reach an agreement for implementing modalities to end the crisis; establishment and management of an inclusive transitional period; and the adoption and implementation of political reforms necessary to meet the aspirations of the Libyan people.

- On 19 March 2011, the ad hoc committee members met in Nouakchott, Mauritania, where they planned to travel to Libya the next day to meet with the parties. Their request to enter Libya was denied by the intervening forces, who started bombing Libya on the same day.

- On 25 March 2011, a consultative meeting was convened in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, involving all international stakeholders whose efforts the high-level ad hoc committee commended, and a consensus on the elements of the AU roadmap was reached.

- The ad hoc committee visited Libya on 10–11 April 2011 where they met with Libyan authorities, who accepted the AU. They later met with the members of the National Transitional Council (NTC), who were unwilling to comply with the AU roadmap.

- On 26 April 2011, the AU Peace and Security Council meeting at ministerial level reviewed the situation in Libya. On the eve of this meeting, the ad hoc committee engaged in discussions with the Libyan parties. A month later, in view of the continued deterioration of the situation in Libya, the AU Assembly convened an extraordinary session. It reiterated the need for a political solution, and called for an immediate end to all attacks against civilians and a ceasefire that would lead to the establishment of a consensual transitional period, culminating in elections that would enable the Libyans to freely choose their leaders. The assembly stressed the imperative for all concerned to comply with both the letter and spirit of UNSC Resolution 1973.

Added to this was the extensive travelling undertaken by Ping, the then-chairperson of the AU Commission, to foreign capitals including Paris, London, Brussels, Washington, DC and Rome in a bid to explain the AU roadmap and seek the support of international partners for it. Many other actions were continuously carried out by the AU, all of which emphasised the need for dialogue with Western powers and declared its efforts towards a ceasefire between the conflicting parties in Libya. Even though the AU expressed its general support for Resolution 1973, it equally established concerns regarding military intervention and declared the need for a peaceful solution within an African framework.

Issuing its first binding ruling against a state, the African Court on Human and People’s Rights ordered Libya to “immediately refrain from any action that would result in loss of life or violation of physical integrity of persons”,3 stating that failure to do so could constitute a breach of human rights obligations. This position and the efforts of the AU thus negated the claim that the international community had no choice but to intervene militarily, and that the alternative was to do nothing. Not only did the AU roadmap provide an alternative that was active, practical and non-violent, but a number of other proposals were also put forward and equally favoured. For example, the International Crisis Group (ICG) published a statement on 10 March 2011, arguing for a two-point initiative:4

- The formation of a contact group or committee drawn from Libya’s North African neighbours and other African states with a mandate to broker an immediate

- Negotiations between the protagonists were to be initiated by the contact group and were aimed at replacing the current regime with a more accountable, representative and law-abiding

These proposals, especially the latter, were backed by the AU and were aligned with the views of many major non-African states such as Russia, China, Brazil and India, and even Germany and Turkey. The ICG detailed these initiatives and added provisions for the deployment of an international peacekeeping force to secure the ceasefire under a UN mandate. This was done before the debate that concluded with the adoption of UNSC Resolution 1973. Thus, before the UNSC vote approving military intervention, a worked-out proposal had been put forward, which addressed the need to protect civilians by seeking a rapid end to the fighting and set out the main elements of an orderly transition to a more legitimate form of government. These proposals were clearly ignored by the intervening states under the argument that only military intervention could stop the regime’s repression of civilians. Yet, many argued that the way to protect civilians was not to intensify the conflict by intervening on one side or the other, but to secure a ceasefire, followed by political negotiations.

The weaknesses and strengths of Resolution 1973 and the AU plan were evident in their outcomes. The outcome of Resolution 1973 is, without doubt, indicative of a poorly constructed and badly implemented solution. This mission, which was structured on humanitarian goals and ended on 31 October 2011, 11 days after the murder of Gaddafi, reflects one of two scenarios. First, the death of Gaddafi constituted such a reduced threat against civilians that no additional airstrikes were required to protect them. Second, the bombing had achieved its ultimate objective: the fall of the dictator and the opposition’s victory. But an operation that was justified in purely humanitarian terms was ultimately stretched to achieving an eminently political objective: the removal of a government and its replacement by that of the rebels.

This clearly differentiates Western solutions to African problems with what has become known as ‘African solutions to African problems’, which in the Libya case was incarnated by the AU roadmap out of the crisis. The difference between both solutions (the AU roadmap and NATO intervention) is what has always differentiated Western orchestrated solutions from African solutions. African solutions refer to those solutions that are initiated by Africans and implemented by Africans. Such African solutions, if given a chance, can be sustainable and if they finally stop the crisis, the chances of falling into the same problems are slim. According to Charles Nyuykonge,5 this is because conventional interventions tend to be more exclusive and are aimed at punishing human rights offenders, focus more on the outcome, sideline the ‘bad guy’ and stress justice as the primary objective for peace, while African interventions are peculiar in their more inclusive nature, with focus on reconciliation and pragmatic confidence-building steps, and emphasis on the process and efforts to build confidence among disputing parties. A few examples of conflicts in which African solutions have been used are the Cameroon–Bakassi case over the Bakassi Peninsula, the Burundi Peace processes, and the resolution of the Biafra war. African solutions and interventions emphasise sustained dialogue between disputants, unlike Western-led conventional methods, which are aimed at quickly conducting elections and sending some people to the International Criminal Court (ICC).

Similar factors can be deemed to have led to the uprisings in North Africa, but the peculiarity of Libya cannot be ignored. Arab transitions show unavoidable specificities according to different national histories and colonial legacies. The special institutional shape of Jamahiriya,6 the redistributive logic of the Libyan rentier state, the weakness of civil society, the security apparatus of Gaddafi’s regime and the exceptional decolonisation after the Italian defeat during the Second World War testify to the uniqueness of the Libyan case among the Arab uprisings. While the Tunisian and Egyptian uprisings challenged the regimes at their centre stages, symbolically occupying the heart of the respective capital cities, in Libya the rebellion was located in Benghazi, far away from the centre of Gaddafi’s power. The rebellions in Cairo and Tunis were perceived and then proceeded as uprisings of the whole country against unfair and corrupt regimes, while the Cyrenaica (eastern coastal region of Libya) uprising was intended in Tripoli as a revolt of the eastern part of the country against the western region. It is true that the Libyan rebellion erupted in Benghazi on 15 February 2011 and was echoed after a few hours in Tripoli, but in actuality only Cyrenaica was able to challenge the regime.7 This region was clearly marginalised; it was not only economically impoverished but its high level of unemployment further catalysed its need for a change in power. In 2010, this region’s unemployment level was as high as 30% – one of the highest rates among the North African countries.8 The speed with which the uprising took a violent turn could have served as a pointer to its complicated nature, and the need for a plan that would bring all disputing parties to the negotiating table.

The AU roadmap was doomed to fail, due to the presence and role of external forces. The support enjoyed by the NTC clearly gave them an upper hand over Gaddafi, and from that perspective they were not ready to engage in dialogue. Gaddafi’s willingness to accept the AU plan should have been exploited to avoid the bloodshed that ensued during and after his demise. It is now evident that the intervention complicated rather than solved the Libyan crisis, as it not only incited inter-regional confrontation between areas such as Tripolitania and Cyrenaica, but also created factions – inside both regions and all over the country – between different armed groups over the control of state resources,9 power and autonomy.

Today, Libya is referred to as a failed state by many commentators. Whether right or wrong, it is evident that Libyan society has deteriorated to a point where it has become a case of concern – not just for Libyans, but also for Africa and the international community as a whole. Of all the lessons that can be learned from the Libyan crisis of 2011, the most glaring is the malfunction within the AU. As Professor Jean Emmanuel Pondi puts it: “…[I]t is how difficult it is for the African Union to speak with one voice and project a coherent position within Africa on the world stage in times of crisis.”10 Many other lessons can be learned, as has been suggested by many commentators,11 and solutions to the existing problems have been proposed on numerous occasions

– but for any solution to work, there must be political will. When Kwame Nkrumah first spoke of African solutions for African problems, he was aware of the fact that this can only work in the context of African unity. The AU should therefore be a body that not only propels values of unity within the continent in its actions and discourse, but those values must resonate in its stance. In the Libyan crisis, can it be said that the AU did nothing? As demonstrated already, it evidently carried out many actions that, according to Ping, went unreported or were manipulated to suit a hostile agenda. If this political will among African leaders can be harnessed, it can lead to the implementation of most, if not all, of the proposed solutions by African intellectuals and leaders.

In an effort to determine which solution was better suited for the Libyan crisis, recourse can be made to the qualitative comparative analyses (QCA) method, as developed by Charles Regin in 1987.12 According to Lise Morje Horward and Van der Lijn Jaïr,13 the presence or absence of the following factors determine the success or failure of an intervention:

A willingness and sincerity from disputants and stakeholders; B impartial security to all disputants and stakeholders;

- adequacy of knowledge of, and familiarity with, the remote and immediate causes of the conflict;

- support and cooperation from important outside actors and parties such as the UN, the AU and the European Union, to cite just a few;

- blurred timelines in operations’ deployment; F competent personnel and leadership;

- broad and long-term vision;

- coordination of internal and external mandates of the operation; and I allowing stakeholders to own and drive the peacebuilding

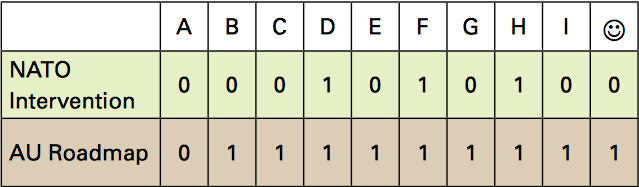

Table 1 depicts these factors and the NATO and AU solutions. The 🙂 symbol represents the outcome of the combined effect of the factors on the peace operation.

Table 1: Qualitative Comparative Analyses Depicting Foreign Intervention by NATO and the AU Roadmap

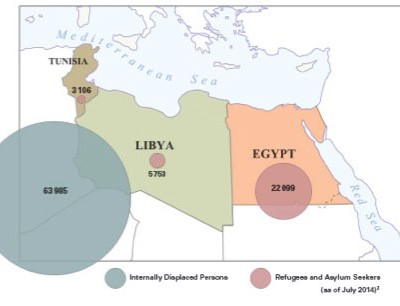

In Table 1, the presence of a factor is indicated by a 1, while its absence is indicated by a 0. The outcome indicates that the AU roadmap had greater chances of succeeding – if not solving the conflict, at the very least preventing the current situation in Libya – and recourse should have been made to it. However, the strategy pursued by the UNSC has exacerbated other humanitarian crises in the region whilst failing to resolve the situation in Libya. It would have been prudent to fully consider the consequences of military intervention before implementing it. A military intervention needs to be able to contain all the armed sides of the conflict, not only one.14 The numerous problems of civilian protection, establishment of the rule of law, control of all the different armed groups, and displacement and stopping crimes against humanity have clearly overwhelmed the current government and the United Nations Support Mission in Libya (UNSMIL). There are no sufficiently robust mechanisms in place in Libya currently that are capable of dealing with such a multitude of problems. At this point, the NTC has to make frantic efforts to reconcile all the different factions within Libya, if Libyans are to have any reason to hope again. Libya should be a lesson to the international community that in Africa dwells the solution to its problems, and greater value should be given to African efforts.

Endnotes

- Yuksel, Pinar (2012) Operation Unified Protector and Humanitarian Intervention with Security Council Authorization: Intra Vires? Ankara Law Review, 9 (1), p. 54.

- Ping, Jean (2011) ‘African Union Role in the Libyan Crisis’, Available at: <http://pambazuka.org/en/category/aumonitor/78691> [Accessed 5 January 2015].

- African Court of Human and People’s Rights Provisional Measures Order, in the Matter of African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights v. Great Socialist People’s Libyan Arab Jamahiriya, Application No. 00412011, 25 March 2011, p. 3.

- Roberts, Hugh (2011) Who Said Gaddafi had to Go? London Review of Books, 33 (22), pp. 8–18.

- Charles Nyuykonge is a senior researcher at the African Centre for Constructive Resolution of Disputes (ACCORD). This statement was made at a talk he delivered to students at the International Relations Institute of Cameroon (IRIC) in Yaoundé, in January 2015.

- Jamahiriya has to do with the concept of ‘popular state’ with direct democracy. It stems from the Arabic words ‘joumhouria’, which means ‘republic’ and ‘jamahir’, which means ‘masses’. The country changed its name from the Arab Libyan Republic in 1969 to the Jamahiriya Arab Peoples Socialist Republic on 12 March 1977 at Sebha. [Pondi, Jean Emmanuel (2013) Life and Death of Muammar Al Qadhafi, What Lessons for Africa? Yaounde: Editions Afric’ Eveil, p. 35.]

- Morone, Antonio Maria (2012) Post-Qadhafi’s Libya in Regional Complexities. ISPI Analisis, 166, p. 5.

- Varvelli, Arturo (2010), Libia: vere riforme oltre la retorica? Luglio, Analysis No. 17, p. 3, as cited in Morone, Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Pondi, Jean Emmanuel (2013) op. cit., pp. 75–101.

- Ibid., pp. 75–95; and Glazebrook, Dan (2014) ‘A War that Brought Total Societal Collapse; The Lessons of Libya’, Counterpunch, November, Available at: <http://www.counterpunch.org/2014/11/12/the-lessons-of-libya/> [Accessed 5 January 2015].

- Ragin, Charles (1987) The Comparative Method: Moving Beyond Qualitative and Quantitative Strategies. California: University of California Press, pp. 19–125.

- Morje, Lise (2007) UN Peacekeeping in Civil Wars. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 8–11. Also see Van der Lijn, Jaïr (2009) If Only There were a Blueprint! Factors for Success and Failure of UN Peace-building Operations. The Hague: Clingendael Institute and Radboud University Nijmegen, pp. 3–12.

- Dominguez, Alvaro (2012) ‘International Intervention and Its Humanitarian Consequences in Libya and Beyond: An Unresolved Issue’. Available at: <https://www.opendemocracy.net/alvaro-mellado-dominguez-tom-pittrashid/international-intervention-and-its-humanitarian-consequence> [Accessed 8 January 2015].