Introduction

The complexities of contemporary violent conflicts in Africa, coupled with the need to engage more holistic models of conflict management that prioritise social structures and relations, have given rise to participatory approaches at all levels of conflict management. Participatory media provides ample opportunities to challenge elitist models of communication and also creates space for interactive processes that reinforce a sense of shared identity in communities affected by violent conflicts. This article conceptualises participatory media and explores the potential of participatory communication methodologies for rebuilding fractured social relations and facilitating reconciliation in conflict communities. Examples of participatory media practices in post-conflict communities in Kenya, Nigeria and South Africa are presented to project the potential of this approach for conflict transformation.

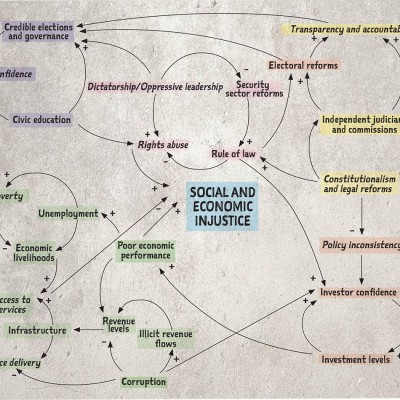

Following the counterproductive role of media technologies and practitioners in the Holocaust, Rwandan genocide, Kenyan elections, Nigerian sectarian conflicts and South African xenophobic crisis, the media has been construed as a threat to conflict resolution in many societies. In many African countries, the media is associated with ethical and technical shortfalls, which has impeded its performance, especially in areas of nation-building and conflict prevention.1 While this has long hampered the constructive application of media practices in peacebuilding, it has drawn the attention of scholars and donors to the media’s potential for peacebuilding in recent times.2 The assumption is that the media’s potential for conflict escalation can be harnessed and deployed for the de-escalation of conflicts.3

In the last 20 years, the emerging field of media and peacebuilding has experienced an unprecedented growth, and has been accompanied with policies and practices which project that the media can create new frontiers to redefine conflict management.4 New theories, such as peace journalism and conflict-sensitive journalism, have drawn the attention of scholars and practitioners to the potentials of constructive reportage for the de-escalation of violence and for peacebuilding. While these models have been embraced in most parts of the world, they have also generated controversies on the ethical obligations of the media to society.5

On a similar note, the inclusion of community members in the design and production of local media content has opened up opportunities for social change, which have been harnessed by development practitioners to stimulate social transformation in different parts of the world. The strength of these participatory models of communication has been bolstered by recent developments in information technologies, which have tipped the traditional horizontal models of communication to favour the participation of “users” in the generation and circulation of media content. This, in turn, articulates voices and stories that have been long ignored by the mainstream media. By amplifying the voices of those affected by structural and social irregularities, participatory media practices are gaining recognition for shaping social, economic, political and cultural processes and institutions. This transformative capacity underscores the place of community-driven media initiatives in driving sociopolitical transformations in modern times, and which must be extensively deployed for dialogue and reconciliation in communities that have been affected by violent conflicts.6

Constructive media practices for conflict transformation are expected to create spaces for dialogue in conflict contexts.7 In this light, participatory media practices have been credited with providing cross-sectional forums for discussing issues like tolerance, conflict experiences, human rights, forgiveness and trust, which are crucial for transforming social structures and attitudes in conflict societies. The interactions and socialisation that accompany the planning and production of media content can provide individual healings that could have spill-over effects in the community. Although not too popular in conflict interventions, the incorporation of participatory media production in some post-conflict communities in Africa has elicited significant changes that must be explored.8 This article therefore examines some of these cases to highlight the potential of participatory media practices for conflict transformation.

Defining Participatory Media

Simply put, participatory media includes practices that empower community members with knowledge and technical skills to create visual, audio, theatrical, musical and textual representations of social, political, economic and cultural issues affecting them, with the ultimate aim of stimulating dialogues, experiential learning and social change. Participatory media practices are closely linked to participatory action research (PAR), whose core aim is community empowerment for social change. PAR was developed out of the need to liberate marginalised communities from oppressive socio-economic structures and empower them to influence positive social changes in their communities.9 By incorporating the participants into iterative processes of research, PAR goes beyond understanding social problems to seeking solutions to them. This approach has been necessitated by the emerging need to engage the repertoire of knowledge outside the academic domain.10 This is especially relevant in rural areas, where grassroots contributions in developmental processes have been hindered by the literacy barrier. Thus, participatory processes present an alternate method for marginalised communities to join the development discourse.

Similarly, participatory media provides platforms to document as well as harness local knowledge for collective problem-solving and human development. Typically, participatory media production processes feature joint collaboration between the lead researcher and other members of the community, who become the participants. Most decisions pertaining to production and circulation of the proposed media content are jointly made by the researchers and the participants. The cooperative and dialogical nature of participatory media practices has been known to ignite social change processes that have had effects on attitudes, behaviour, perception and policy change in communities.11 The need to engage participatory media interventions in post-conflict communities is related to the current manifestations of conflicts on the continent. Most violent intergroup conflicts are enmeshed in polarised social institutions and relations that have dire implications for post-conflict relations, as most communities affected by violence usually feature high levels of intergroup tensions.

Participatory media – such as participatory videos (PV) and participatory photography – normally involves a range of capacity-building exercises where participants are facilitated to produce videos on selected themes in their communities, some of which include workshops on video-making, editing, development of themes and storylines, and narration, among others. These sessions usually feature dialogical group settings that Sadan, cited in Tremblay and Oliveira-Jayme,12 notes can serve as an avenue to alter power dynamics or social structures. Constructive interactive sessions facilitate a liberal exchange of conflict experiences between opposing factions, which can illuminate similarities in the pain, loss and scars of the conflicts, thereby leading to a shared conflict narrative that, in turn, fosters a sense of collective identity. The interactions between the symbolic presentations of human experiences and liberal dialogic processes stimulate cognitive reactions that promote the attainment of commonalities. This was manifested during the “Never Again” campaign in Sierra Leone, where participatory communication approaches such as theatre, songs, proverbs, riddles and skits were used to engage victims and perpetrators of violence in storytelling processes that led to the cultivation of shared understandings of the conflict.13 These understandings captured the victims’ pain as well as the perpetrators’ motivations for committing the atrocities.

Participatory communication is linked to one of the major tenets of peace journalism, which is rooted in stimulating change processes in conflict contexts by presenting issues in a manner that elicits constructive dialogues, counters stereotypes and enhances non-violent conflict resolution. Through participatory communication processes, marginalised parties are empowered to project their stories and create images or sounds that counter negative labels and affirm their commitment to peace, as was observed in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. In a community affected with high levels of drug violence, members of the community were trained to create videos that projected positive aspects of the community, to counter the violent labels attached to that community by the mainstream media.14

The establishment of creative forms of engagement for adversarial parties in post-conflict societies is also a route to constructive transformation because it projects the similarities between adversarial parties, thereby giving them opportunities to redefine their relations. In some cases, monuments are jointly erected to serve as a sign of reconciliation and as a reminder of the resolve for peace. The inclusion of storytelling, dancing and healing rituals in the production processes of participatory media have made them forums for healing and reconciliation in post-conflict communities.

Case Studies

Some cases of participatory media practices in post-conflict communities are examined in this section.

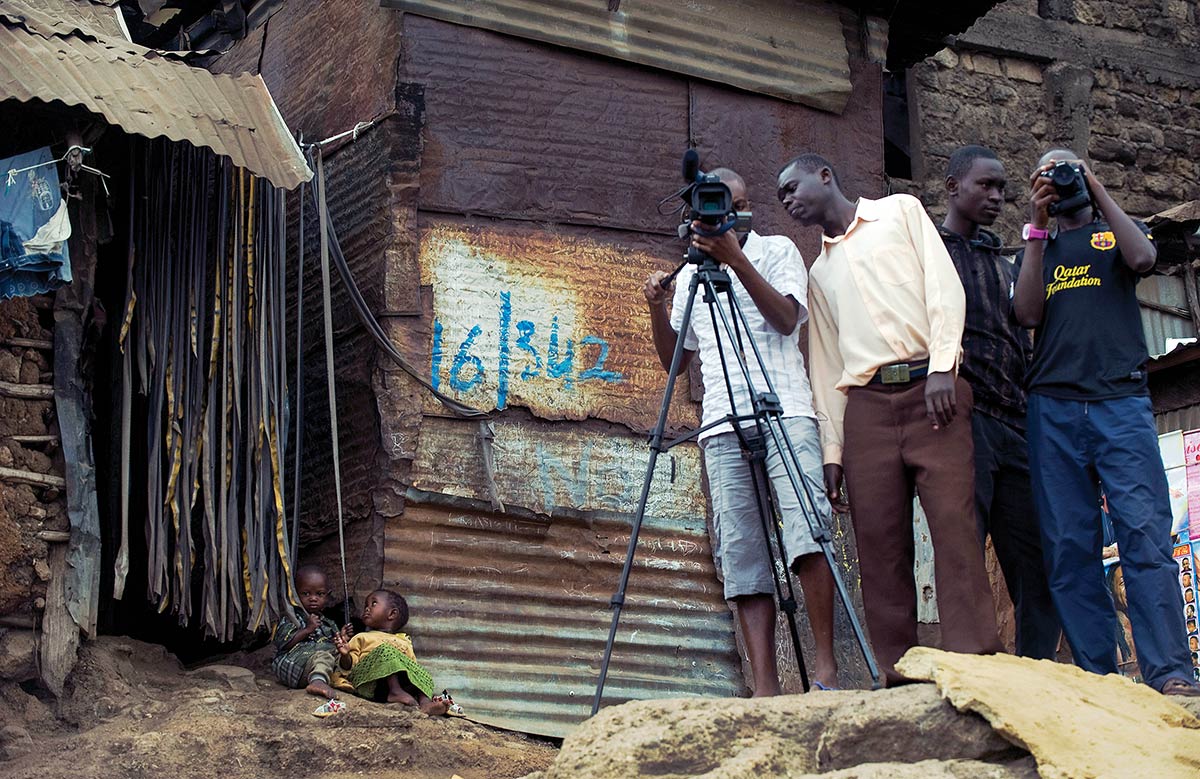

Participatory Photography for Dialogue in Post-conflict Communities in Kenya

The post-election violence of 2007–2008 in Kenya left a number of scars on the communities affected. Apart from the loss of lives and displacement of about 300 000 people,15 the violence fractured social relations between the belligerent tribes. There were widespread feelings of distrust, fear, anger and hatred in the communities. Driven by the need to re-establish communication between the opposing sides and rebuild the social fabric broken by the conflict, Lenses of Conflict and Peace, a participatory photography project, was implemented in Eldoret, Rift Valley to engage members of different ethnic groups in dialogic processes that complemented reconciliatory efforts in the area.16

Some members of the communities were selected to participate in the programme; the selection was done heterogeneously as the participants were drawn from all the tribes in the area. The participants were trained in basic photography, after which they were paired, given cameras and asked to go into the community to capture images that depicted their experiences of the conflict. The major aim was to use the images to create individual narratives of the 2007–2008 election violence and to engage them in a discussion that focused on conflict and peacebuilding. Once the photographs were taken, it generated interactive sessions, with each participant sharing the stories of their pictures and how they related to the conflict. The storytelling sessions were filled with memories, emotions and reflections from all the participants, and eventually culminated in experiential learning processes. The evaluation of the project, though limited, revealed that the interactive sessions played a significant role in the development of a collective understanding of participants’ conflict experiences. It also showed that the dialogues and socialisation stimulated a reversal of antagonistic ethnic labels with some of the participants.17

Participatory Theatre for Social Change in Post-conflict Communities in Nigeria

Several cities in northern Nigeria have been the scene of violent ethno-religious conflicts. These conflicts are normally precipitated by sociopolitical factors but escalate along the lines of ethnicity and religion. In effect, the conflict has fractured social relations between ethnic and religious groups in some areas. To change the attitude of the groups in conflict, the Theatre for Development Centre (TFDC) initiated a series of participatory dramas in some of the worst-affected cities in Kaduna, Kano and Plateau states.18

Participatory drama was strategically used to overcome the barrier posed by language and illiteracy. The major purpose of the plays was to investigate and interrogate conflict narratives, establish commonality and project the need for sustainable peace. The dramas featured the TFDC drama team and some selected members of the communities. The themes of the dramas were developed from data collated on conflict experiences in the area. The dramas were performed in public and were followed by interactive sessions during which other community members were allowed to re-enact certain characters and aspects of the play to aid discussions and provide deeper understanding on the themes of the plays. At the end of the project, the evaluation showed that the project went beyond promoting interaction and socialisation between opposing sides, to stimulating experiential learning and the cultivation of collective narratives on the causes and experiences of the conflict. The project gave insights into the dynamics of the conflict at the local level, which is an essential element of conflict transformation. The attainment of social change in any conflict situation must be informed by a deep understanding of the conflict, the core issues and how the conflict affects the lives of ordinary citizens.19

Participatory Video for Reconciliation in South Africa

The period that preceded the 1994 elections in South Africa was characterised by high levels of political violence that led to unwanted loss of lives in different parts of the country. As typical of most violent conflicts, the post-conflict phase was filled with destructive narratives that made reconciliation a difficult task. Most communities affected by the violence were divided and had feelings of fear, resentment and suspicion. The communities of Kathlehong, Thokoza and Vosloorus in south-east Johannesburg were also affected by these crises. Between 1990 and 1994, over 2 000 people lost their lives to political violence in these communities.20

Due to the need to strengthen communal bonds in these areas, a video dialogue project was introduced to the communities by the Wilgespruit Fellowship Centre in collaboration with the Media Peace Centre and Simunye community organisation. The major goal was to promote reconciliation and cohesion through a community-led video production. In effect, video cameras were given to leaders of two political groups, the African National Congress (ANC) and the Inkatha Freedom Party (IFP), to document the conflict experiences of their communities. After separate recording exercises, a mutual process of editing and collating the stories was conducted to produce a new joint story that was acceptable to all. The joint story was a 90-minute video clip that analysed the conflict and solicited solutions from the community. The video was screened publicly to different segments of the community, and spaces for dialogue on the themes depicted in the videos were created.

The project created interactive sessions that strengthened social bonds in the community and facilitated the development of a common understanding, thereby promoting reconciliation. It also helped to break deconstructive perceptions and stereotypes that were fuelling animosities between both sides. The video went beyond strengthening community bonds to coordinating cooperative efforts for addressing some of the economic and development needs in the community.21

Benefits of Participatory Media in Post-conflict Communities

On a general note, participatory media provides a number of opportunities for groups and individuals to experience and influence positive change in communities affected by conflict. Some of these are:

- It empowers participants with knowledge and skills to bring economic and developmental benefits for themselves and their communities.

- It creates a shared sense of community.

- The circulation of the media output can open opportunities to engage policymakers on pressing socio-economic problems.

- During high-intensity conflicts, when mainstream media structures are dilapidated, participatory media can provide an alternative means of projecting the stories of the communities.

- Participatory media practices provide positive channels for diverting youth energies in post-conflict societies, which is a crucial part of conflict transformation.

- Participatory media can enhance intercultural dialogue and tolerance by providing a physical and social opportunity for diverse groups.

- By offering a space for interaction between perpetrators and victims, it promotes forgiveness in post-conflict communities.

Conclusion

The practice of participatory media empowers communities to undertake collaborative processes for social change in different contexts. The joint inclusion of adversarial groups in the planning and production of strategic local content strengthens their ability to undertake personal and collective actions for peace. This was evident in the participatory projects executed in post-conflict communities in Kenya, Nigeria and South Africa, where community members were engaged in creative media processes for reconciliation. The exchange of conflict experiences through visual and artistic presentation facilitated learning processes through which opposing groups were able to cultivate a shared understanding of the conflict. Moreover, the communicative processes facilitated the deconstruction of stereotypes and the articulation of relational patterns that are crucial for restoring communal bonds in polarised societies or communities. This practice presents a good model for conflict transformation, in line with the growing emphasis on dialogic engagement and localised peacebuilding.

Endnotes

- Odine, Maurice (2013) Media Coverage of Conflicts in Africa. Global Media Journal African Edition, 2, pp. 201–225.

- Hoffmann, Julia (2013) ‘Conceptualizing “Communication for Peace”‘, UPeace Open Knowledge Network Occasional Working Papers, No. 1, Available at: <https://www.upeace.org/OKN/working%20papers/Conceptualizing%20Communication%20for%20Peace%20OKN.pdf> [Accessed 20 April 2016].

- Ibid., p. 4.

- Bratic, Vlado (2013) ‘Twenty Years of Peacebuilding Media in Conflict: Strategic Framework’, UPeace Open Knowledge Network Occasional Working Papers, No. 3, Available at: <https://www.upeace.org/OKN/working%20papers/UniversityForPeaceOKNTwentyYearsOfPeacebuildingMediaInConflictOctober2013.pdf> [Accessed 10 June 2016].

- Puddephatt, Andrew (2006) ‘Voices of War: Conflict and the Role of the Media’, International Media Support report, Available at: <https://www.mediasupport.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/11/ims-voices-of-war-2006.pdf >[Accessed 18 July 2016].

- Pettit, Jethro, Salazar, Juan Francisco and Dagron, Alfonso Gumucio (2009) Citizens’ Media and Communication. Development in Practice, 19(4/5), pp. 443–452.

- Aslam, Rukhsana (2016) Building Peace through Journalism in the Social/Alternate Media. Media and Communication, 4(1), pp. 63–79.

- Bau, Valentina (2015) Communications for Development in Peacebuilding: Directions on Research and Evaluation for an Emerging Field. South-North Cultural and Media Studies, 29(6), pp. 801–17.

- Glassman, Michael and Erdem, Gizem (2014) Participatory Action Research and its Meanings: Vivencia, Praxis, Conscientization. Adult Education Quarterly, 6(3), pp. 20–221.

- Tremblay, Crystal and Oliveira-Jayme, Bruno (2015) Community Knowledge Co-creation through Participatory Video. Action Research, 13(3), pp. 298–314.

- Blazek, Matej and Hranova, Petra (2012) Emerging Relationships and Diverse Motivations and Benefits in Participatory Video with Young People. Children’s Geographies, 10(2), pp. 151–168.

- Tremblay, Crystal and Oliveira-Jayme, Bruno (2015) op. cit.

- Bau, Valentina (2014) Communities and Media in the Aftermath of Conflict: Participatory Productions for Reconciliation and Peace. In Ware, Helen, Jenkins, Bert, Branagan, Marty and Subedi, D. (eds) Cultivating Peace: Contexts, Practices and Multidimensional Models. Newcastle: Cambridge Scholars, pp. 266–282.

- Wheeler, Joanna (2009) ‘The Life that We Don’t Want: Using Participatory Video in Researching Violence. IDS Bulletin, 40(3), pp. 10–18.

- Calas, Benard (2007) From Rigging to Violence: Mapping of Political Regression. In Lafargue, Jerome (ed.) The General Elections in Kenya, 2007. Nairobi: IFRA, pp. 165–185.

- Bau, Valentina (2015) Participatory Photography for Peace: Using Images to Open up Dialogue after Violence. Journal of Peacebuilding and Development, 10(3), pp. 74–88.

- Ibid., p. 83.

- Abah, Oga Steve, Okwori, Jenkeri Zakari and Alubo, Ogoh (2009) Participatory Theatre and Video: Acting against Violence in Northern Nigeria. IDS Bulletin, 40(3), pp. 19–26.

- Ibid.

- Stauffer, Carl (1998) ‘Video Dialogue: An Innovative Tool for Story-telling, Problem-solving and Conflict Transformation’, Available at: <http://s3.amazonaws.com/academia.edu.documents/32179175/VIDEO_DIALOGUE_PAPER.pdf?AWSAccessKeyId=AKIAJ56TQJRTWSMTNPEA&Expires=1468926646&Signature=c6rHrBttiEZdIF1mzuI4q1bdIqs%3D&response-content-disposition=inline%3B%20filename%3DVideo_Dialogue_An_Innovative_Tool_for_St.pdf> [Accessed 17 July 2016].

- Ibid.