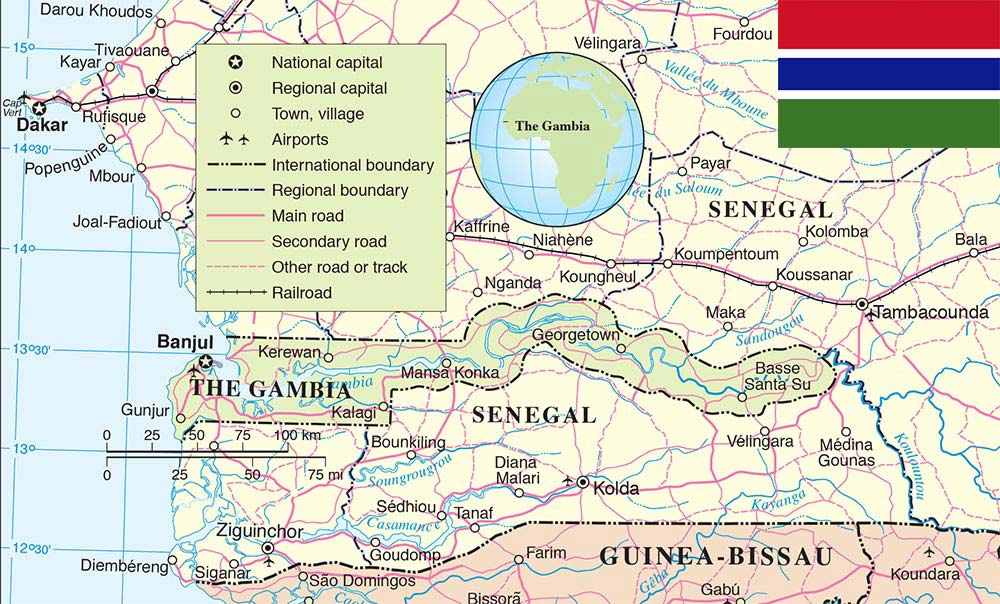

Introduction1

According to the 2017 Global Peace Index, The Gambia has fallen 18 places since 2016 and is among the top five countries to have experienced the largest deterioration of an ongoing conflict situation.2 In addition, The Gambia is facing a range of socio-economic challenges including increasing poverty, high unemployment, a growing rural-urban divide and a decreasing literacy rate.3

Yet despite the country’s fragile socio-economic and political climate, in 2017 The Gambia peacefully transitioned to a new political authority through democratic means. On 1 December 2016, Gambians took to the polls and replaced then-president Yahya Jammeh with the current president, Adama Barrow. Jammeh, who had been in power since 1994, surprised the international community by initially conceding the electoral defeat, and committing to make way for Barrow.4

A week later, however, Jammeh contested the results and, subsequently, declared a state of emergency. In an effort to avert a crisis, the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS), with the support of the United Nations (UN) and the African Union (AU), responded swiftly, launching a series of high-level dialogue efforts and deploying ECOWAS troops to the border. These efforts were successful and President Barrow was sworn into office in January 2017, paving the way for a peaceful political transition.

This transfer of power was heralded as a landmark win for democratic governance on a continent that has struggled to rid itself of the stigma of authoritarian rule. The “New Gambia”, as it is now commonly referred to, is re-engaging with the international community, and political and development initiatives are already underway.

The question remains, however, whether The Gambia will be able to sustain its peaceful state during this transition and in the long term. In an effort to answer this question, this article examines The Gambia through the lens of “sustaining peace” – a concept formally introduced into UN vocabulary in April 2016 by dual resolutions of the Security Council and General Assembly. The resolutions define sustaining peace as “a goal and a process to build a common vision of a society, ensuring that the needs of all segments of the population are taken into account”.5 It is further stated that sustaining peace is “a shared task and responsibility that needs to be fulfilled by the Government and all other national stakeholders”.6 The concept should be seen as flowing through all three pillars of the UN’s work to promote an integrated approach to peace, development and human rights, where peace is seen as both an enabler and an outcome.7

This article highlights three main areas that, in the name of sustaining peace, should be prioritised in The Gambia: youth engagement, women’s empowerment, and transitional justice and rule of law. It explains how investment in these areas prevents the escalation of conflict, and how it contributes to the maintenance of long-term national peace and stability.

Youth Empowerment and Entrepreneurship

The Institute for Economics and Peace has found a strong correlation between “positive peace” (a concept similar to sustaining peace) and the Youth Development Index. While the relationship between youth and peace is not simple or linear, there is evidence that “peaceful and resilient societies can better promote and benefit from youth development and youth-led entrepreneurship”.8 This is especially true in The Gambia, where youth make up 65% of the population.9 Youth unemployment in The Gambia is at 70%, while the ratio of youth unemployment to adult unemployment is 2.3. A major contributor to youth unemployment is lack of access to high-quality education and training systems and a lack of skills, or mismatch between the skills possessed and those demanded in the labour market. This has contributed to young people seeking alternative means of livelihood, including irregular migration and employment in the informal sector.

The youth in The Gambia, however, are a strong force that, during the political impasse, emerged as a political force in the movement challenging Jammeh’s authority. This group of the population was largely responsible for the #GambiaHasDecided movement, by popularising it via social media platforms. This movement was created to ensure the people’s voice was heard through the election results, and played a crucial role in educating Gambians on their rights as voters and in opening space for political debate, especially during the political impasse.10

With the change in government in The Gambia came the expectation of a higher quality of life, with better employment opportunities, greater access to education and improved delivery of social services. The Barrow government has realised this need and has made tackling youth unemployment a priority, offering skills training and apprenticeship schemes through the National Youth Service Scheme. However, a recent survey of 16- to 30-year-olds found that “many young people were unaware of these programmes, or did not believe they were effective”.11 More is needed from the government to communicate opportunities and connect with youth to understand their expectations. The National Youth Council offers an opportunity to establish this link.

The National Youth Council was established in 2000 and has played a central role in empowering Gambian youth during the transition. Several interviewees from civil society and the private sector stressed that there has been little communication from the new government on what is being done and what plans it has for the country. There have only been isolated incidents of protests and demonstrations, but many interviewees warned that these illustrate brewing tensions. The National Youth Council has managed to diffuse a number of protests planned by youth, but the fear is that if youth are not engaged in the short term, their “energy [to bring about change] can easily slip to dissent”.12 There is a sense that they feel responsible for putting this new government in power, so they are anxious to see the results of this change, including more employment opportunities and a better quality of life.13

In addition to the government initiatives, several private institutions have launched initiatives in an effort to meet the demand for improved access to and delivery of education and training. One example is the UN Conference on Trade Empretec programme, which works to “help existing and aspiring entrepreneurs become innovative and internationally competitive small and medium-size enterprises”.14 The initiative focuses on assisting entrepreneurs through an “integrated behavioral change program anchored on two flagship methodologies: Entrepreneurship Training Workshops and a comprehensive Business Development Support and Advisory Service”.15 With the support of the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), the initiative was set up in 2014 and has worked with 2 500 entrepreneurs across six regions in the country so far. It delivers seven programmes that focus on entrepreneurship-training workshops, including specific programmes for youth and women. Investment in these programmes could not only help expand their reach but would also assist in developing and strengthening the skills youth need to increase their economic opportunities.

Due to The Gambia’s high youth population, prioritising initiatives aimed at empowering youth should be a central focus of the new government’s work for the purpose of sustaining peace within the country. In this regard, among other things, investing in entrepreneurship as a means of job creation is an investment in sustaining peace.

Women’s Empowerment

The connection between women’s empowerment, stability and peace is supported by a wealth of evidence. Indeed, “gender equality is a stronger predictor of a state’s peacefulness than its level of democracy, religion, or gross domestic product (GDP). Where women are more empowered, the state is less likely to experience civil conflict or go to war with its neighbors.”16 Moreover, there is a positive correlation between economic growth and gender equality and evidence that increasing “women’s participation and representation in leadership and decision-making positions leads to higher levels of peacefulness and better development outcomes for society”.17

The Gambia ranked 173 out of 188 on the UNDP’s 2016 Gender Inequality Index, with women still struggling to access economic resources, healthcare and education.18 Women and girls continue to be disadvantaged due to patriarchal norms and practices, including in customary law, which does not allow women to inherit land, and which does not give women equal status in judicial processes. In addition, women cannot control or own land, despite their predominant role in farming and the reduction of malnutrition. Women disproportionately face financial access barriers that prevent them from participating in the economy and from improving their lives, including lack of access to credit and bank accounts.19 Many women have poor access to social services, healthcare and education, and work in low-wage jobs. Gender-based violence is a frequent occurrence in The Gambia, with 20% of women (15–49 years) having experienced physical and/or sexual violence at least once in their lifetime.20 Further, despite being illegal, underage marriage is still prevalent, with 30% of women (20–24 years) married before the age of 18, forcing many girls to leave school prematurely.21 Fully 75% of women (15–49 years) have undergone female genital mutilation,22 and the maternal mortality rate in 2015 was 706 deaths per 100 000 live births – which, while it has been decreasing over the past 25 years, is still high in comparison to the global average.23

The Jammeh regime did demonstrate a commitment to addressing gender inequality by, among other things, empowering women through establishing the National Women’s Council within the Department of State for Women’s Affairs. The National Women’s Council acts as a forum for women to access legal support. The ensuing adoption of the Women’s Act (2010), the Sexual Offences Act (2013) and the Women’s Amendment Act (2015), banning female genital mutilation, also signified progress in advancing the rights of women. In 2012, The Gambia adopted a National Action Plan on Women, Peace and Security, recognising the impact that conflicts in neighbouring countries continue to have on women in the country. Enforcement, however, has been a challenge. This is particularly the case in the provinces, where certain cultural practices, such as female genital mutilation, are still prevalent. Further, there is concern that many in the country associate strict enforcement of these laws with the former regime, and that the change of government will result in greater disregard for these protections.

Furthermore, women in The Gambia face financial exclusion, mainly due to limited access to land and credit. Social and cultural norms make it difficult for women to acquire vital information on available financial services, while the lower literacy rate among women (35.5% compared to 45.7% for men) means more women have difficulty processing and comprehending the information they do have access to.24 Simply being able to open a bank account and access credit would help expand the economic opportunities available to women in The Gambia.

There are however, efforts by non-state actors to address some of the challenges faced by women, and thereby advance gender equality and equal opportunities for women. The National Women Farmers Association (NAFWA), for example, is a non-governmental organisation (NGO) with the aim of promoting commercially viable agriculture and food security among female farmers, to move them from subsistence agriculture towards economic self-sufficiency. NAFWA builds women’s capacity to open and manage small businesses and advocates for more land ownership rights for women. The Association of Non-Governmental Organisations (TANGO), an umbrella organisation of NGOs operating in The Gambia, takes a slightly different approach. It works to educate men in The Gambia on how women can contribute to society, and how they can support women in this effort. It is also teaching fathers the importance of education for girls, especially in rural regions.

Taking into consideration the strong links between gender equality and sustaining peace, initiatives targeted at increasing women’s empowerment and improving gender equality should be prioritised on The Gambia’s national agenda. This should include ensuring the mobilisation of necessary resourcing of organisations working to empower women, the upholding of laws promoting gender equality and women’s empowerment, and efforts to ensure that women have equal access to all resources and opportunities in the country.

Transitional Justice and Good Governance

The resolutions sustaining peace emphasised the importance of addressing the root causes of conflict, strengthening the rule of law and fostering national reconciliation. This includes ensuring “inclusive dialogue and mediation, access to justice and transitional justice, accountability, good governance, democracy, accountable institutions, gender equality and respect for, and protection of, human rights and fundamental freedoms”.25 Transitional justice refers to the ways that countries which have emerged from periods of conflict and repression address mass human rights violations, for which the traditional justice system cannot provide the necessary response. Some of the aims of transitional justice include establishing a functioning rule of law system and accountable institutions in society, which enable individuals to voice grievances and seek justice for past and present human rights abuses. Having strong national institutions “plays an important role in promoting and monitoring the implementation of international human rights standards at the national level”.26

In line with this approach, when Barrow assumed office, he committed to enhancing and improving “human rights, access to justice and good governance for all”.27

To achieve this, the government has formulated a plan that consists of efforts to improve the rule of law and address grievances of the past though a transitional justice process. After decades of bad governance, the Barrow administration appears dedicated to regaining the trust of the population, strengthening the country’s institutions and rebuilding The Gambia’s historical reputation as a beacon of democracy on the continent.

To strengthen the rule of law in the country, the government will be reforming the judicial sector and solidifying proposals for the establishment of a national human rights commission. This will include a comprehensive review of existing criminal justice legislation to reform laws restricting political and civic freedoms, particularly those relating to freedom of expression. The government intends to establish more courthouses and ensure that judges and magistrates can work full time in rural areas, where justice is often difficult to administer and access. These efforts to expand the judicial infrastructure will help make people more aware of their rights.

Another key area of concern in regard to the rule of law is the personal security of Gambians during the political transition. Paradoxically, during the Jammeh rule, the country was considered one of the safest on the continent. The Jammeh regime had zero tolerance for crime, with harsh punishment. The intension behind this was to ensure that The Gambia remained a safe country and attractive for tourists.28 However, since Jammeh left office, reports of rape, home break-ins and petty crime have been rising, leaving many concerned that the new government is not prioritising the safety of Gambians.29 To strengthen the population’s trust in the security forces, the government has begun to undertake security sector reform. Central to this process is the formulation and adoption of a comprehensive national security policy, along with the necessary legislation. The policy would aim to identify threats to national security, clarify the functions of the country’s key security institutions, and structure them in line with the provisions of the policy, ultimately strengthening the rule of law and accountability in the country.

The government has also committed to establishing a truth and reconciliation commission to address the gross human rights violations of the past. This process seeks to hold perpetrators accountable for their actions, provide closure for those affected by human rights violations, help the government establish and document an accurate historical record of events, and pay reparations to victims.30 The Ministry of Justice held a three-day National Stakeholders Conference on Justice and Human Rights in May 2017 to conceptualise the mechanism. The conference identified challenges and gaps in the justice system, and allowed for discussions on the design of a transitional justice strategy and the establishment of applicable transitional justice mechanisms for The Gambia moving forward.31

Many interviewees, however, highlighted that there is anxiety around whether transitional justice should be the priority for The Gambia, and how it should tie in to other aspects of development. Many question why the central focus has been transitional justice when there is widespread lack of access to electricity and a need for economic growth.32 While the focus of the new government should not rest exclusively on transitional justice, initiatives that aim to strengthen the rule of law and deal with past violations are important for enabling national reconciliation and the unity needed for the country to move peacefully forward into a new era.

Conclusion

As The Gambia moves forward in its transitional period and solidifies its national development plans, the new government must address transitional justice alongside investment in economic growth, gender equality and youth employment, among other things, to maintain peace and stability throughout the country. Neglecting any of these elements risks disgruntling a population seeking improvements in its quality of life and demanding justice for past abuses.

Looking at a country through the lens of sustaining peace, it is peace rather than conflict that is the starting point. This requires identifying and relying on what is still working in a society, rather than on what is broken and needs to be fixed. A sustaining peace approach focuses not just on restoring stability after violence but also on investing in structures, attitudes and institutions associated with peaceful societies. Further, it focuses on all countries – regardless of whether or not they have experienced conflict. Using this approach can help keep attention on countries, such as The Gambia, that are not faced with current violent conflict as such, despite internal vulnerabilities and external pressures, but are nonetheless in need of long-term investment efforts to sustain peace.

Endnotes

- This article is based on the author’s previous work, including Connolly, Lesley (2018) Chapter 9: Sustaining Peace in the “New Gambia”. In Mahmoud, Youssef, Connolly, Lesley and Mechoulan, Delphine (eds) Sustaining Peace in Practice: Building on What Works. New York: International Peace Institute.

- Institute for Economics and Peace (2017) ‘Global Peace Index 2017’, p. 25, Available at: <http://visionofhumanity.org/app/uploads/2017/06/GPI-2017-Report-1.pdf>.

- There was an 18% increase in the number of poor people in The Gambia between 2010 and 2015. As rural poverty is rising, the wealth gap between rural and urban Gambians is widening. In Banjul, 10.8% of the population live below the poverty line, compared to 69.8% of those in rural Gambia. The country’s literacy rate is 40.1% and is lower for women (35.5%) than for men (45.7%). Only 51% of the working age population is employed, and unemployment rates are even higher in rural areas. World Bank (2017) ‘Macro Poverty Outlook for Sub-Saharan Africa: The Gambia’, Available at: <http://pubdocs.worldbank.org/en/214601492188159621/mpo-gmb.pdf>; and Government of The Gambia (2017a) National Development Plan (Draft). The Gambia: Government of The Gambia.

- Connolly, Lesley (2017) ‘The Gambia: An Ideal Case for Prevention in Practice’, IPI Global Observatory, 4 October, Available at: <https://theglobalobservatory.org/2017/10/the-gambia-an-ideal-case-for-prevention-in-practice/>.

- UN Security Council (2016) ‘Security Council Resolution 2282 (2016) [on Post-conflict Peacebuilding]’, 27 April, S/RES/2282 (2016), Available at: <http://www.securitycouncilreport.org/atf/cf/%7B65BFCF9B-6D27-4E9C-8CD3-CF6E4FF96FF9%7D/s_res_2282.pdf>; and UN General Assembly (2016) ‘General Assembly Resolution 70/262 (2016) Review of the United Nations Peacebuilding Architecture’, 27 April, UN Doc. A/RES/70/262, Available at: <http://www.un.org/en/development/desa/population/migration/generalassembly/docs/globalcompact/A_RES_70_262.pdf>.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Mahmoud, Youssef, Makoond, Anupah and Naik, Ameya (2017) Entrepreneurship for Sustaining Peace. New York: International Peace Institute.

- Government of The Gambia (2017a) op. cit.

- See: <www.facebook.com/GambiaHasDecidedPage/>.

- Hunt, Louise (2017) ‘Meet the Gambian Migrants under Pressure to Leave Europe’, IRIN, 20 July, Available at: <www.irinnews.org/feature/2017/07/20/meet-gambian-migrants-under-pressure-leave-europe>.

- Connolly, Lesley (2017) Interview with the chairman of the National Youth Council in June. The Gambia.

- Ibid.

- Empretec: The Gambia (2017) ‘About Us’, Available at: <www.empretecgambia.gm/about-us-basic>.

- Ibid.

- Mechoulan, Delphine, Mahmoud, Youssef, Ó Súilleabháin, Andrea and Leiva Roesch, Jimena (2016) The SDGs and Prevention for and Sustaining Peace: Exploring the Transformative Potential of the Goal on Gender Equality. New York: International Peace Institute.

- Ibid.

- United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) (2017a) The Human Development Report 2016. New York: United Nations.

- UNDP (2017b) The Gambia Sustainable Development Goals Roadmap: United Nations MAPS Mission to The Gambia Report. New York: United Nations.

- Ibid.

- United Nations and Government of The Gambia (2017) The Gambia United Nations Development Assistance Framework (UNDAF) 2017–2021. The Gambia: United Nations.

- UNDP (2017b), op. cit.

- World Health Organization (WHO), United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF), United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA), World Bank Group and United Nations Population Division Maternal Mortality Estimation Inter-Agency Group (2016) Maternal Mortality in The Gambia 1990–2015. Geneva: WHO.

- Government of The Gambia (2017a) op. cit.

- UN Security Council (2016) op. cit.; and UN General Assembly (2016) op. cit.

- Mahmoud, Youssef and Athie, Aissata (2017) Human Rights and Sustaining Peace. New York: International Peace Institute.

- United Nations and Government of The Gambia (2017) op. cit.

- Connolly, Lesley (2017) Interview with WANEP representative in The Gambia in June. The Gambia.

- Ibid.

- United Nations and Government of The Gambia (2017) op. cit.

- Government of The Gambia (2017b) Report of the National Stakeholder Conference. The Gambia: Government of The Gambia.

- Connolly, Lesley (2017) Interview with UN country team in The Gambia in May. The Gambia.