Most African countries implemented social distancing measures, including lockdowns, to contain the spread of the coronavirus following the declaration of a pandemic on 11 March by the World Health Organisation (WHO). The regulations that were enacted by governments included restricting the movement of people, the closure of schools and businesses, limiting the operations of transport services, and ‘stay at home’ policies. In the last few weeks, there has been an increase in the number of incidents of arrests and/or fines issued to people for failure to comply with the rules and regulations. What is uncommon about the situation is that many of the transgressions people were being arrested or fined for, would not have been deemed worthy of arrest before the COVID-19 measures were introduced.

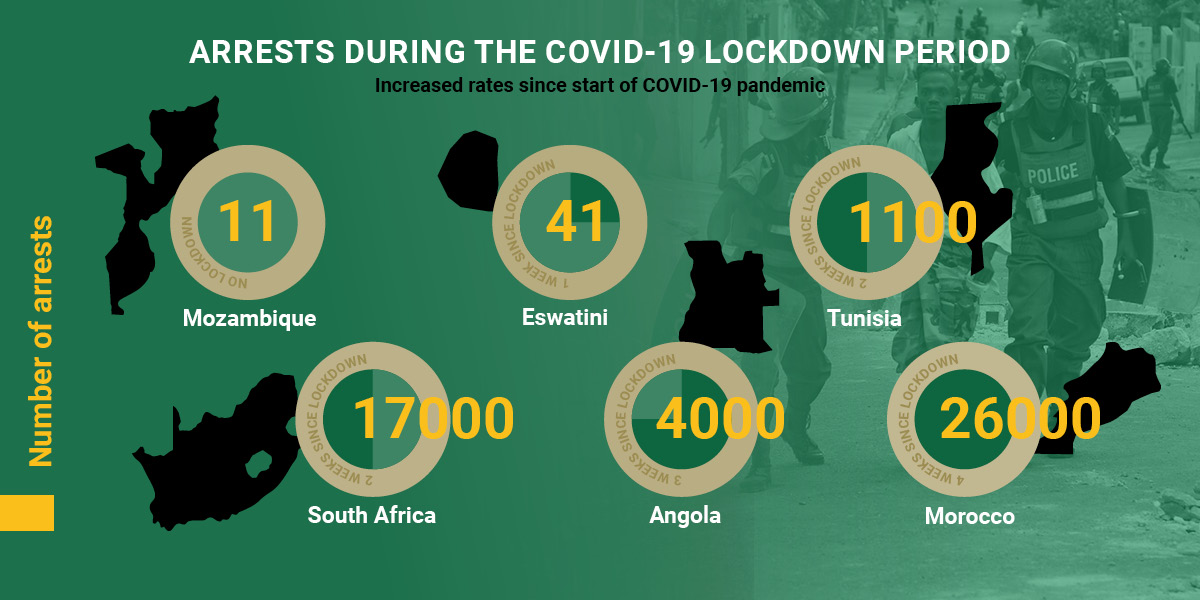

Six countries in particular reflected a high number of arrests. In Angola, three weeks into its lockdown, 4100 people were detained for disobedience, 2100 motorcycles were seized, and 70 people detained for price speculation. In Morocco, one month into its lockdown, more than 28,000 people were arrested for violating the state of emergency regulations, with most of these arrests taking place in and around Casablanca. In Tunisia, two weeks into its lockdown, 1119 people were arrested and imprisoned for ten-days for failing to comply with quarantine rules and regulations.

In Mozambique, taxi drivers reportedly blocked main roads in the port city of Ncala and riots broke out in protest of the authorities’ decision to seize motorbikes and ban motorcycle taxis for contravening social distancing measures. Although 11 people were arrested, the ban was later lifted and a new requirement put in place for drivers and passengers to wear masks. Similarly, in Malawi, citizens took to the streets to protest against the government’s announcement that the country would go into a lock-down.

In South Africa, the country with the highest COVID-19 infection rate in Africa, very strict lockdown measures have been in place since late March. One such measure was the prohibition of the sale of liquor, which potentially contributed to a considerable decrease in violent crime in the first two weeks of the lockdown. It was reported that murder cases dropped from 326 to 94; rape cases dropped from 699 to 101; and cases of assault with intent to inflict grievous bodily harm dropped from 2,673 to 456. Whilst certain violent crimes decreased, other forms of crime and social unrest increased. Four weeks into its lockdown, 397 schools were burglarised and vandalised. In early April liquor stores were looted in light of the ban on liquor sales, and as a result additional army personnel were deployed to troubled areas. Four trucks undertaking deliveries in the community of Bishop Lavis in Cape Town, were pelted with stones and robbed of its cargo. Two of these trucks were transporting food parcels to bring relief to the community. In its second week alone, over 17 000 arrests were made for non-compliance of the lockdown measures in South Africa. In Eswatini, 41 people were arrested in contravention of the lockdown regulations.

Several of the offences people are being arrested or fined for appear to be related to people attempting to buy or sell basic items such as food and medicine, or protesting in frustration of being prevented from doing so. The vast majority of people in Africa are self-employed in the informal economy and a great number of them earn their livelihood on a daily basis to support their families. For them the lockdowns have meant a sudden total loss of income. Faced with the impossible choice of adhering to the lockdown rules or feeding their families, they choose the latter.

The increase in arrests will also place a heavy burden on criminal-justice systems. There is likely to be processing delays and many people will be unable to afford to pay fines. This could lead to a further increase of people in holding cells and in prisons, where there is a high risk of spreading the virus. The high number of arrests will thus add further stress to state institutions and is likely to lead to rising levels of tensions between ordinary people, security services and governments. This could further lower levels of public trust and increase the likelihood of social unrest and violence.