The current era has witnessed the increasing need by the African Union (AU) and subregional organisations to be more involved as first responders to conflict situations in the region. This trend, which involves the use of preventive diplomacy efforts, mediation, peace support operations, peacekeeping, peacebuilding and post-conflict reconstruction and development efforts, has situated Africa at the forefront of peace processes on the continent. A number of developments explain this trend, including the specific provisions in the United Nations (UN) Charter, specifically Chapter VIII, which provides for regional arrangements to deal with peace and security matters, provided that “such matters relating to the maintenance of international peace and security as are appropriate for regional action provided that such arrangements or agencies and their activities are consistent with the Purposes and Principles of the United Nations”.1

The role of regional mechanisms in conflict intervention is further necessitated by the reality that conflict in the region provides a setback to regional development, and has the capacity to impact beyond the region. Another reason for the increasing ownership of primary responsibility towards conflict resolution in Africa by African institutions is the disillusionment with “Western interventions”, double standards and the conditions that come with such. In addition, the reality is that collaboration, cooperation and concerted efforts are critical for resolving complex conflicts, such as the violence in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC). Increasingly, African leaders are realising that the intervention of Western actors is often determined by Western priorities, which currently seem to be stretched due to the focus on countering violent extremism and terrorism in regions such as Somalia, Libya, Mali and Syria; dealing with the challenge of immigration; and other issues such as the implications of the recent exit of Britain from the European Union.

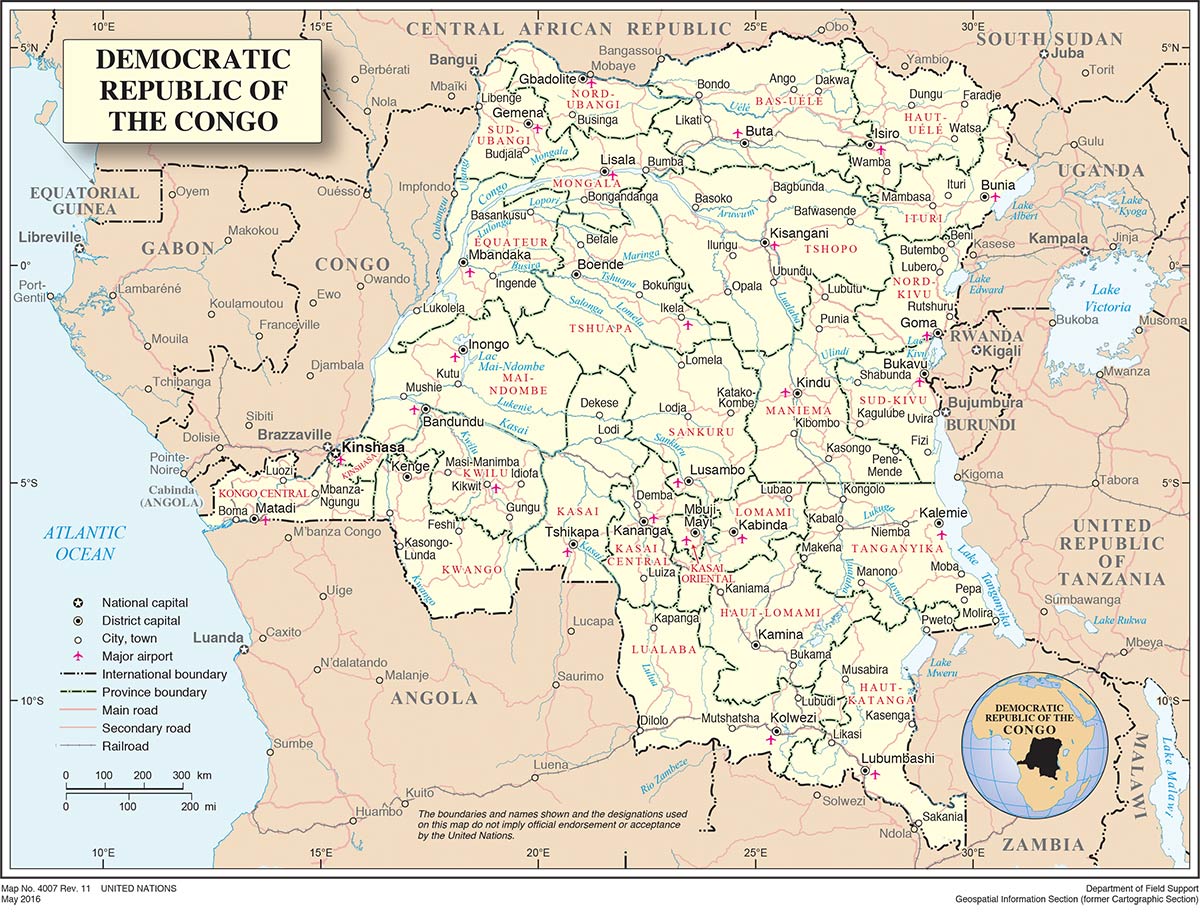

The DRC further provides an example of a conflict that not only has regional and transboundary dimensions and impact, but also requires regional efforts towards sustainably resolving it. The DRC is bordered by nine countries: Angola, Burundi, Rwanda, Uganda, Republic of the Congo, Central African Republic (CAR), South Sudan, Tanzania and Zambia. Thus, the DRC conflict, particularly its intractability, has numerous risks for neighbouring countries and the region, due to the negative consequences from unstable conflict spillovers.2 Furthermore, the emphasis on “African Renaissance”, which was revitalised during Thabo Mbeki’s South African presidency, has found expression in various AU policy documents, among others the New Partnership for Africa’s Development (NEPAD), the African Solidarity Initiative (ASI)3 and Agenda 2063. The deliberate and determined involvement of African organisations in intervention efforts in the DRC is based on the recognition that this conflict risks becoming forgotten, and that its endurance will breed intractability and an ingrained culture of violence.

Against this background, the AU and regional organisations – such as the Southern African Development Community (SADC) and the International Conference on the Great Lakes Region (ICGLR) – have been at the forefront of working with both the UN and national actors in the DRC to ensure that they combine expertise and strengths to address the drawn-out conflict in the eastern DRC.

Arguing that SADC was the central regional organisation involved in conflict intervention efforts in the DRC, this article examines the background to the conflict in the DRC, provides a brief appraisal of the factors and issues that have contributed to its intractability, and discusses the role of African organisations in finding solutions to the crisis. The article further evaluates SADC interventions, drawing lessons on how these efforts can be strengthened and bolstered for lasting peace.

SADC is a regional economic community (REC) in the southern African region that seeks to promote sustainable economic growth and socio-economic development through integration, good governance and durable peace and security. Although it is only about 25 years old, SADC’s roots can be traced back to the 1960s and 1970s, when the leaders of newly independent states and national liberation movements mobilised together politically, diplomatically and militarily as the Frontline States (FLS) to unite against apartheid South Africa’s expansionism and to support further decolonisation. In 1980, the Southern African Development Coordination Conference (SADCC) was born as further consolidation of the FLS, with the main objective of coordinating development projects in the region. Due to the changing political environment, SADCC was transformed into SADC in 1992,4 and its mandate was broadened to focus not only on economic development and regional integration, but also to pursue peace and security objectives.

Conflict in the DRC: Background and Overview

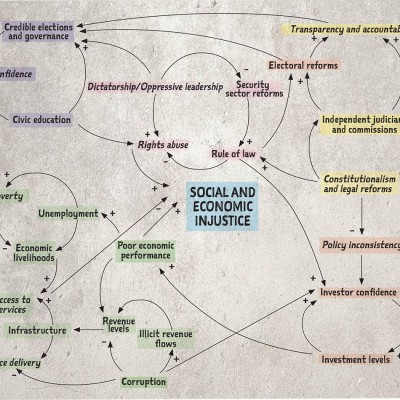

Since its independence in 1960, the DRC has not known peace, and its problems have a long history dating as far back as the colonial era. The Belgian administration during the colonial era established a political system that was more focused on the exploitation of national resources than on addressing the needs of its citizens.5 The conflict in the DRC is one of the most complex on the continent, as it often connects political, economic, institutional, social and security factors into one complicated and interconnected web of intractability. During the period 1996–1997, the conflict in the DRC was referred to as “Africa’s first world war” – a phrase that highlighted the regional nature of this conflict. This period was followed by what is often referred to as the second Congo War (1998–1999), which involved more than nine countries including Rwanda, Uganda, Burundi, Angola, Namibia, South Africa, Tanzania and Zimbabwe. A 2014 UN report acknowledges the setbacks in stability and conflict resolution in the DRC, pointing out the volatility of the situation in the country and the continuing sporadic attacks, particularly in the eastern DRC.6 On the one hand, the eastern DRC is characterised by communal violence and internal armed conflict among local groups, and community security groups or local militias. On the other hand, the conflict is also about political power contestations and competition to access state resources, which often play out at the national and local levels.

There are several actors involved in the DRC conflict. Local actors include the government and armed groups, while external actors include the DRC’s neighbours, some members of the international community and multinational corporations (MNCs). Apart from land and forests, the DRC has extensive mineral resources including coltan, tin, copper, diamonds and gold. This resource abundance has made the DRC a theatre for the battle for control and ownership of these natural resources. The global scramble for natural resources and the increasing demand for energy has also made the DRC susceptible to conflict. In fact, resource-rich regions of the DRC, such as the eastern part of the country and Katanga, have often been the battle ground for conflict. The conflict in the DRC also reflects a huge security vacuum and weak institutional capacity, as the government continues to struggle to extend state control and authority in many parts of the country. A 2014 UN Development Programme report notes the challenge of poor governance at political, administrative, economic, judicial and security levels in the DRC. Furthermore, the social dimensions of the DRC conflict are epitomised by the manipulation of identity issues by various leaders, particularly around citizenship and nationality laws, coupled with the politics of exclusion and the instrumentalisation of ethnicity and the Congolese identity. The issue of contested citizenship in the DRC, especially of those people of Rwandophone origin,7 partly contributed to the Kivu conflict, where the Alliance des Forces pour la Libération du Congo–Zaïre (AFDL) was formed as a coalition to topple Mobutu Seso Seko with support from Rwanda, Uganda and Angola.

Over the past three decades, the DRC has experienced a number of interventions by a wide range of actors including the UN, AU, SADC, ICGLR, state institutions and eminent persons. SADC has been at the centre of most of these interventions. While these peace efforts have resulted in some notable peace agreements8 and milestones for the consolidation of peace – such as the 2006 and 2011 elections – the situation in the DRC remains fragile, particularly as state authority has not been fully established across the entire country.

Even though significant advances have been made towards securing peace in the DRC, the eastern part of the country remains significantly affected by conflict. Communal violence and internal armed conflict among local groups, community security groups or local militias, which take advantage of the coalescing of cross-border insurgencies and regional conflict complexes, characterises that area. Armed groups control large parts of the territory, and civilians are at the receiving end of the consequences of this conflict: death, sexual violence and exploitation, and extortion. Several explanations have been given for the continued violent conflict in the eastern DRC, including the politics of exclusion, competition for land and natural resources, economic motives for violence, absence of the rule of law, weak state capacity and limited territorial coverage, impunity for serious human rights abuses, and external interference.

SADC Interventions in the DRC

The DRC is a member of SADC, having been admitted into the regional body in 1998 when Laurent Kabila’s forces defeated the ruling Mobutu. Since then, the relationship between SADC and the DRC has largely been that of cooperation. Although the DRC is a member of multiple RECs including the East African Community, the ICGLR, the Common Market for East and Southern Africa (COMESA) and the Intergovernmental Authority on Development (IGAD), SADC interventions in securing peace and stability in the DRC have been more salient and sustained. SADC’s conflict interventions in the DRC have ranged from the involvement of the regional bloc and coalitions of the willing within southern Africa to the involvement of individual countries such as Angola, Malawi, Namibia, South Africa, Tanzania and Zimbabwe, among others.

Since its independence in 1960, the DRC has been a site of continuous attempts at conflict resolution.9 Several peace processes and conflict interventions have been undertaken in the DRC, including political and diplomatic efforts leading to negotiations between warring parties; peacekeeping interventions; and stabilisation missions. As early as 1998, SADC intervened in the DRC through a combination of military intervention and mediation. In 1998, there was a military intervention from three SADC countries – Angola, Namibia and Zimbabwe – under the auspices of the SADC Allied Forces. This intervention was authorised by the SADC Organ on Politics, Defence and Security Cooperation (SADC Troika), which was then chaired by Zimbabwe. The intervention came shortly after the invasion of the DRC by Rwanda and Uganda, and the subsequent request by the then-president of the country, Laurent Kabila, for SADC to assist him with curbing the aggression from neighbours. Under the auspices of the SADC Allied Forces, the military intervention was codenamed “Operation Sovereign Legitimacy” (OSLEG). Its objectives were to ward off rebels (which were notably sponsored by Rwanda and Uganda), to secure the DRC territory, and to protect civilians. Although there are mixed assessments on the efforts of the SADC Allied Forces’ intervention in the DRC,10 what remains a point of agreement is that the four years of troop presence and active military engagement in the DRC helped the country to regain its authority and sovereignty. The intervention by the SADC Allied Forces arguably was concluded with the signing of the Lusaka Agreement in 1999.

Apart from intervening militarily in DRC, since the 1990s SADC has also supported mediation and preventive diplomacy efforts in the country. Carayannis notes: “Many of the efforts to mediate a peaceful settlement during the second Congo war were SADC-driven and much of the mediation in both wars was undertaken by leaders in the SADC region.”11 Indeed, through the mediation processes of various African leaders, SADC has been at the forefront of advancing dialogues and negotiations to end the various conflicts in the DRC. In fact, the Lusaka Peace Agreement and the Inter-Congolese Dialogue were facilitated by SADC leaders – including the former president of Botswana, Ketumile Masire; the late president of South Africa, Nelson Mandela;12 President Frederick Chiluba of Zambia;13 and former president of South Africa, Thabo Mbeki,14 among other eminent personalities. During the earlier phases of the SADC-led mediation processes in the DRC (1996–1997), Mandela largely facilitated the dialogue between Mobutu and Kabila. This was followed by the mediation process led by Chiluba, which resulted in the signing of the Lusaka Ceasefire Agreement on 10 July 1999. This agreement provided for the cessation of hostilities; the withdrawal of foreign groups; disarming, demobilising and reintegrating of combatants; and the re-establishment of government administration.

Following the Lusaka Ceasefire Agreement, further SADC-led mediations, led initially by Masire and then by Mbeki, gave birth to the Inter-Congolese Dialogue. In July 2002, two peace accords were signed between the DRC and the Rwandan and Ugandan governments, providing for the two countries to pull their troops out of the eastern DRC.15 These peace processes paved the way for the adoption of political pluralism and the holding of democratic elections in 2006, which somewhat strengthened the legitimacy of state institutions and the central government. The involvement of SADC in these mediation processes reflected a huge amount of political will by the leaders of this regional mechanism to decisively bring an end to the political crisis in the DRC. It is from such SADC-mandated mediation efforts in the DRC that a report, written by Carayannis for the Centre for Humanitarian Dialogue, observes that “despite deep regional divisions, regional actors can (and did) initiate and successfully negotiate agreements to end conflicts in which large and important portions of that region are participants in the conflict”.16 While these mediation efforts by SADC have had mixed results, there is overwhelming consensus that they largely contributed to halting violence, ceasing hostilities and paving the way for a transitional government, which ultimately led to the first post-conflict elections in 2006.

Following the SADC interventions and the 2006 elections, the conflict in DRC continued, necessitating extended conflict intervention by SADC. In January 2008, another peace deal was signed between the DRC government and rebel groups, which paved the way for the elections in 2011. In 2013, the Regional Pact on Peace and Security and the Peace, Security and Cooperation Framework for the DRC (the “Framework of Hope”) was signed by 11 countries, and sought to build stability by addressing the root causes of the conflict and fostering trust between neighbours.17 These peacemaking efforts have somewhat led to the reduction of some direct forms of violence and the cessation of hostilities.

One way SADC has been demonstrating its assertiveness in the DRC is through its cooperation with the AU on peace and security issues, and in devising strategies for peacemaking, peacekeeping and peacebuilding in the country. For example, SADC has established a joint office with the AU in the DRC, which is tasked with supporting peacemaking and peacebuilding initiatives. A seminar report by the Centre for Conflict Resolution observes: “SADC has attempted to make a meaningful contribution to combating violence in the DRC. The organisation has recognised the need to establish institutional structures to engage in a robust approach to peacebuilding and reconstruction in the DRC. In particular, it has established a joint office with the African Union (AU) in Kinshasa.”18 Based on its actions in the DRC, it is apparent that SADC is demonstrably committed to the ideals of the AU in pursuing peace and security and regional cooperation. This is a reflection of SADC’s work towards enhancing and strengthening its military and diplomatic efforts in the DRC, but it is also a reflection of the regional mechanism’s operational capacity. SADC continues to monitor the security and political situation in the eastern DRC, with a view to determining political and other courses of action. In July 2015, the ministers of SADC’s Interstate Defence and Security Committee (ISDSC) met in Pretoria to review the security situation in the region, including the eastern part of the DRC.19

Another example of the determined involvement of southern African leaders in efforts to bring lasting peace to the DRC can be discerned from the role played by SADC, the ICGLR and the Force Interventions Brigade (FIB), which operates with a Chapter VII mandate under the main UN peacekeeping mission, the UN Organization Stabilization Mission in the DRC (MONUSCO).20 SADC was one of the institutions (including the UN, AU and the ICGLR) that made the call to deploy the FIB in eastern DRC in 2013.

Essentially, the FIB is a regional peacekeeping force, comprising 6 000 troops from SADC countries (Malawi, Tanzania and South Africa), which seeks to stabilise the eastern DRC and prevent mass atrocities. FIB was established in March 2013, following the signing of the Framework Agreement for Peace, Security and Cooperation for the DRC and the Region,21 and adoption of UN Security Council Resolution 2098 of 2013. With the mandate to pursue armed groups and negative forces in the eastern DRC, and ultimately help the government to regain control of its territory, the FIB has already recorded notable successes, particularly the surrender of the M23 rebel movement.22 This development resulted in the Kampala Dialogue and Declarations for Peace and the Nairobi Declaration for Peace in the Eastern DRC23 in December 2013.

The FIB’s intervention has also resulted in a partial neutralisation of the Forces démocratiques pour la libération du Rwanda (FDLR). These cumulative processes of securing the DRC have given a sense of optimism to that government – to the extent that in March 2015, the government called upon MONUSCO to begin withdrawing its peacekeeping troops from the country, citing the reason that the DRC is “ready to assume the responsibility of securing its state.”24 The role of SADC’s Force in securing the DRC territory has led some observers to contend that “the east of the DRC, for the first time in many years, is no longer held hostage by rebel groups with significant links to neighbouring governments, though these undoubtedly remain”.25 However, despite these initial successes, the FIB has not yet been able to completely disarm the FDLR. This is likely because of the significant size of this armed group, and the fact that the FDLR is more spread out, is deeply embedded in local communities and is located in difficult-to-reach areas.

Review and Evaluation of SADC’s Interventions in the DRC

Despite the recognition of the need for Africa to become more involved in its peace and security processes, one of the challenges that SADC interventions in the DRC face is the limited institutional capacity of both the continental and regional organisations to support and sustain conflict prevention, peacemaking and peace support processes. For example, while the AU, SADC and ICGLR have the political will to lead interventions in the DRC, the reality is that these organisations still depend on external support to mobilise resources and drive the peace and security agenda. The focus on “African ownership” of peace and security challenges and processes is likely to remain hollow, particularly if those seeking to drive such processes do not have adequate resources to fully operationalise this. The limited funding has meant that the SADC-led FIB in the DRC operates under the guidance of MONUSCO, with most funding coming from the UN. While this institutional set-up is reflective of UN-REC cooperation, on the ground it could sometimes present command and control challenges. Against this background, SADC is currently in the process of fully operationalising the SADC Standby Force, and it is hoped that this force will be well resourced and capacitated to be readily deployed in situations, such as that of the eastern DRC.

While it is notable that SADC has been significantly involved in processes to facilitate the securing of the Congolese territory, there is still a long way to go for DRC state authority to be fully reinserted. To date, a number of armed groups still remain in the DRC and the majority are markedly localised, with the exception of the FDLR. Other prominent armed groups that are active in the DRC include the Ugandan Allied Democratic Forces (ADF) and the Burundian Forces nationales de libération (FNL). According to Stearns and Vogel, at least 70 armed groups remain active in the DRC.26 The proliferation of armed groups in the DRC could be a reflection, not of the weakness of SADC, but of the limited opportunities of young men, who find opportunity in joining rebellion. This could also point to the challenges of the demobilisation, disarmament and reintegration (DDR) processes that have followed the signing of most of the peace deals since 1999. Discontentment with reintegration processes has often been accompanied by the re-arming and remobilisation of groups, and a relapse into violence and conflict.

The continuation of armed violence in the eastern DRC might require not only renewed commitment and capacity by the state to secure its territory, but a review of the current modus operandi of regional interventions in the country. It is in this cyclical context of violence that SADC’s conflict prevention, management and resolution processes are being tested, and would require continued exploration of how to design and effect innovative approaches towards peace. Since 2011, the approaches to negotiations have somewhat shifted, with the DRC government no longer keen to offer incentives to armed groups who surrender. While this might reduce the tendency to regroup by armed groups who do not get government positions, it is not clear how such an approach would address the root causes of conflict, as some armed groups often cite political exclusion as a reason for taking up arms.

Another challenge that SADC faces in intervening in the DRC is the multiplicity of actors in this theatre of conflict. This, coupled with the lack of any existing system of coordinating peace and security actors, has meant that efforts to bring lasting peace to the DRC are not as coordinated and harmonised as would be expected. Admittedly, SADC institutions in the DRC currently work closely with the AU Liaison Office in the country, as well as with the UN, especially MONUSCO. Perhaps, what is needed is a regional or country liaison office that could help to coordinate the various political, diplomatic and security processes that are being led by SADC. In addition, a liaison office would also ensure that the work of the SADC Secretariat being undertaken by structures such as the SADC Mediation Unit and the SADC Regional Early Warning Centre (REWC), among others, is harmonised. Such a liaison office could also provide necessary technical capacity for the various initiatives by SADC member states and coalitions of the willing that are currently involved in conflict interventions in the DRC.

While SADC notably espouses solidarity among member states, based upon a common history of providing an affront against colonialism and foreign domination, in some instances SADC’s interventions in the DRC reveal that it has not always reflected absolute consensus. There are a few instances where member states have sometimes had differing perspectives, priorities and approaches to bringing lasting peace to the country. For example, the SADC Allies intervention in the DRC in 1998 is often cited as a case reflecting divided opinions among SADC political leaders. For example, Mandela, who was then the chair of SADC, did not initially agree with a military intervention, which was proposed by Mugabe, who was then the chair of the SADC Organ on Politics, Defence and Security Cooperation (SADC Troika). Some SADC member states preferred diplomacy as a strategy to end the DRC crisis, while Zimbabwe, Angola and Namibia argued from a standpoint of collective security, highlighting that a military intervention was imperative since the DRC was facing an act of aggression from its neighbouring countries. Making reference to the SADC Treaty and the SADC Protocol on Politics, Defence and Security Cooperation – which cumulatively provide that the regional community’s member states have to support any member state facing aggression from one or several foreign forces – the SADC Allies (Zimbabwe, Namibia and Angola) intervened militarily in the DRC, despite the controversy, and limited support from the international community.

SADC’s interventions in the DRC could be better enhanced if it made more salient overtures to work with civil society organisations (CSOs). While the mediation processes undertaken especially by South Africa (Inter-Congolese Dialogue) created space for the participation of CSOs, this could be further broadened, especially in the post-conflict reconstruction and development phase. Civil society partners could be key in unlocking potential avenues for achieving sustainable peace, as they are closer to the ground and possess both vertical and horizontal linkages with conflict actors. Therefore, SADC’s efforts in the DRC would be better enhanced through the design and implementation of coherent national peacebuilding processes, which encourage people-to-people and people-to-state engagements.

Conclusion

SADC’s intervention in the DRC is rooted in the appreciation of the interconnectedness of African countries, and the recognition of the imperative for mutual dependence. Its response to the DRC conflict has taken several forms, ranging from military intervention, mediation and supporting peacebuilding processes to advocacy with the international community. An examination of the history of SADC’s involvement in the DRC since 1998 reveals a degree of consistency, determination and commitment to securing not only the DRC, but the region. Evidently, SADC initiatives in the DRC seek to secure the state and restore state authority, protect civilians and, ultimately, build long-term sustainable peace.

While SADC has been consistent since the late 1990s in being part of the solution to the DRC crisis, it has not been an easy journey. The fact that the conflict in the DRC is still not fully addressed, particularly in the eastern part of the country, reflects the complex environment in which SADC operates. In addition, there are multiple actors and players in the DRC who sometimes act as spoilers to the peace process, and SADC has to navigate these intricacies with political dexterity. Indeed, while the DRC reflects the multiplicity of conflict intervention actors, ranging from the UN and AU to other RECs and bilateral initiatives, SADC has increasingly recognised that it is not a lone player in the DRC. It has adopted strategies of partnering not only with the AU, but with other regional organisations such as the ICGLR, to ensure that there is a harmonised approach to the resolution of conflict in the country. The “Framework of Hope” – signed in 2013 by 11 countries, the UN, AU, ICGLR and SADC – provides an indication that RECs and members of the international community are increasingly adopting a collaborative approach to addressing conflicts in the region. However, this is still a work in progress.

Going forward, there is a need to design and implement effective UN–AU–REC modes of cooperation in the DRC to ensure that interventions are harmonised. While the conflict in the DRC might seem daunting, SADC’s interventions highlight the increased engagement of regional actors in promoting peace and security, and is evidence of the evolving nature of regional security cooperation. Indeed, SADC has exhibited a strong sense of solidarity on matters relating to peace and security, and its role in the DRC reflects the increasing primacy of African actors in conflict resolution in the region.

Endnotes

- United Nations (n.d.) ‘Charter of the United Nations: Chapter VIII: Regional Arrangements, Article 52:1’, Available at: <http://www.un.org/en/sections/un-charter/chapter-viii/index.html> [Accessed 18 July 2016].

- Mutisi, Martha (2016) Mass Atrocity Prevention in Africa: SADC Case Study and the Democratic Republic of Congo. In Whitlock, Mark (ed.) The African Task Force on Mass Atrocity Prevention and the Budapest Centre for the International Prevention of Mass Atrocities and Genocide, Budapest, Report of the African Task Force, August 2016 (forthcoming).

- The African Solidarity Initiative (ASI) was launched by AU member states on 13 July 2012 to mobilise enhanced support from within the continent for postâ€conflict reconstruction and development in African countries emerging from conflict. The ASI launch occurred within the context of the AU Post-Conflict, Reconstruction and Development (AU PCRD) Policy, which was adopted in Banjul in June 2006.

- The Southern African Development Community (SADC) was launched on 17 August 1992 when the Windhoek Declaration and the SADC Treaty were signed by the Southern African Development Coordination Conference (SADCC) leaders as well as Namibia, which gained its independence in 1990. The transformation of SADCC into SADC gave the regional organisation legal status through the SADC Treaty (1992), which underscores the peaceful settlement of disputes as one of the fundamental principles of the organisation.

- Kisangani, E. (2012) Civil Wars in the Democratic Republic of Congo, 1960–2010. Boulder: Lynne Rienner Publishers.

- United Nations Security Council (2014) ‘Report of the Secretary-General on the Implementation of the Peace, Security and Cooperation Framework for the Democratic Republic of the Congo and the Region’, (S2014/153), Available at: <http://www.securitycouncilreport.org/atf/cf/%7B65BFCF9B-6D27-4E9C-8CD3-CF6E4FF96FF9%7D/s_2014_153.pdf.>

- A Rwandophone is defined as anyone who resides in the DRC but is of Rwandan origin, and this applies to both Hutus and Tutsis.

- These peace processes include the Chiluba mediation, which led to the Lusaka Ceasefire Agreement in 1999 and called for the immediate cessation of hostilities; the withdrawal of foreign groups; the disarming, demobilising and reintegrating of combatants; and re-establishment of government administration. This was followed by the Masire and Mbeki mediation processes, which culminated in the Sun City Talks, also known as the Inter-Congolese Dialogue.

- Kisangani, E. (2012) op. cit.

- Institute for Security Studies (2004) ‘Hawks, Doves or Penguins: A Critical Review of the SADC Military Intervention in the DRC’, Paper 88, April, Available at: <https://www.issafrica.org/uploads/PAPER88.PDF> [Accessed 18 July 2016].

- Carayannis, Tatiana (2009) ‘The Challenge of Building Sustainable Peace in the DRC’, Background paper, Centre for Humanitarian Dialogue, July, Available at: <http://www.hdcentre.org/uploads/tx_news/69DRCpaper.pdf> [Accessed 18 July 2016], p. 11.

- The late President Nelson Mandela was especially instrumental in the SADC-backed negotiations that led to the signing of the agreement between Mobutu Sese Seko and the then-leader of the Banyamulenge rebel group, Laurent Kabila.

- President Frederick Chiluba of Zambia played a critical role in the regional SADC-backed mediation process that led to the signing of the Lusaka Peace Agreement in 2002.

- President Thabo Mbeki of South Africa largely brokered the Pretoria agreement, which was signed on 16 December 2002.

- See the ‘Agreement Between the Governments of the Democratic Republic of the Congo and the Republic of Uganda on Withdrawal of Ugandan Troops from the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Cooperation and Normalisation of Relations Between the Two Countries’, Available at: <http://www.usip.org/sites/default/files/file/resources/collections/peace_agreements/drc_uganda_09062002.pdf>. Also see: ‘Peace Agreement Between the Governments of the Republic of Rwanda and the Democratic Republic of the Congo on the Withdrawal of the Rwandan Troops from the Territory of the Democratic Republic of the Congo and the Dismantling of the Ex-FAR and Interahamwe Forces in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC)’, Available at: <http://www.usip.org/sites/default/files/file/resources/collections/peace_agreements/drc_rwanda_pa07302002.pdf> [Accessed 11 August 2016].

- Carayannis, Tatiana (2009) op. cit.

- These 11 countries are Angola, Burundi, Central African Republic, DRC, Republic of the Congo, Rwanda, South Africa, South Sudan, Tanzania, Uganda and Zambia. The Peace, Security and Cooperation Framework for the DRC and the Region was facilitated by the UN Special Envoy for the Great Lakes Region of Africa. The Framework of Hope came on the heels of the adoption of Resolution 2098 by the UN Security Council, and the appointment of Mary Robinson as the Special Envoy of the Secretary-General for the Great Lakes. Robinson’s mandate focuses on encouraging the parties to the framework to deliver on their commitments while supporting regional efforts to reach durable solutions in the Great Lakes region.

- Centre for Conflict Resolution (2010) Post-conflict Reconstruction in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC)’, Policy Advisory Group Seminar Report, Available at: <http://dev.ccr.org.za/images/pdfs/Vol_36_post_conflict_reconstruction_mar2011.pdf> [Accessed 10 August 2016].

- Agência Angola Press (ANGOP) (2015) ‘Ministers at SADC’s Defence, Security Organ Meeting’, 20 July, Available at: <http://www.portalangop.co.ao/angola/en_us/noticias/politica/2015/6/30/Minister-SADC-Defence-Security-organ-meeting,0c7ea8e1-cb5a-402e-a2b3-e8b1be201e4c.html>.

- Sheeran, Scott and Case, Stephanie (2014) ‘The Intervention Brigade: Legal Issues for the UN in the Democratic Republic of the Congo’, Available at: <http://www.scribd.com/doc/267461654/The-Intervention-Brigade-Legal-Issues-for-the-UN-in-the-Democratic-Republic-of-the-Congo#scribd> [Accessed 25 May 2016].

- The Peace, Security and Cooperation Framework Agreement for the Democratic Republic of the Congo and the Region was signed on 24 February 2014 by 11 African countries (Angola, Burundi, CAR, DRC, Republic of the Congo, Rwanda, South Africa, South Sudan, Tanzania, Uganda and Zambia). In addition, leaders of four regional/international organisations also signed the agreement: the Chairperson of the AU Commission, the Chairperson of the ICGLR, the Chairperson of SADC and the Secretary-General of the UN. For details, see: <http://www.un.org/wcm/webdav/site/undpa/shared/undpa/pdf/SESG%20Great%20Lakes%20Framework%20of%20Hope.pdf> [Accessed 24 May 2015].

- The rebel March 23 Movement (Mouvement du 23-Mars, or M23), also known as the Congolese Revolutionary Army, was a rebel military group based in the eastern areas of the DRC, mainly operating in the province of North Kivu. The M23 rebels were named after a peace agreement they signed with the Congolese government on 23 March 2009, when they were fighting as part of a group calling itself the National Congress for the Defence of the People (CNDP). Many CNDP fighters were integrated into the Congolese army, the Armed Forces of the DRC (FARDC). However, a number of CNDP troops mutinied, in response to their alleged discontent towards the implementation of the peace agreement, as well as their dissatisfaction with their pay conditions within the Congolese army.

- The Nairobi Declaration was facilitated by President Uhuru Kenyatta of Kenya. The M23 agreed to cease the rebellion, demobilise and transform itself into a legitimate political party, while the DRC committed to grant amnesty to M23 members and release those under detention for acts of war and rebellion.

- For details, see: Author unknown (2015) ‘DRC Calls for an End to UN Peacekeeping Mission’, Aljazeera, 19 March, Available at: <http://www.aljazeera.com/news/2015/03/drc-calls-peacekeeping-mission-150319200034331.html> [Accessed 15 July 2015].

- For details, see: Shepherd, Ben (2014) Beyond Crisis in the DRC: The Dilemmas of International Engagement and Sustainable Change. Research paper. London: Chatham House

- Stearns, Jason K. and Vogel, Christoph (2015) ‘The Landscape of Armed Groups in the Eastern Congo’, Congo Research Group, Center on International Cooperation at New York University, Available at: <http://congoresearchgroup.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/The-Landscape-of-Armed-Groups-in-Eastern-Congo1.pdf> [Accessed 11 August 2016].