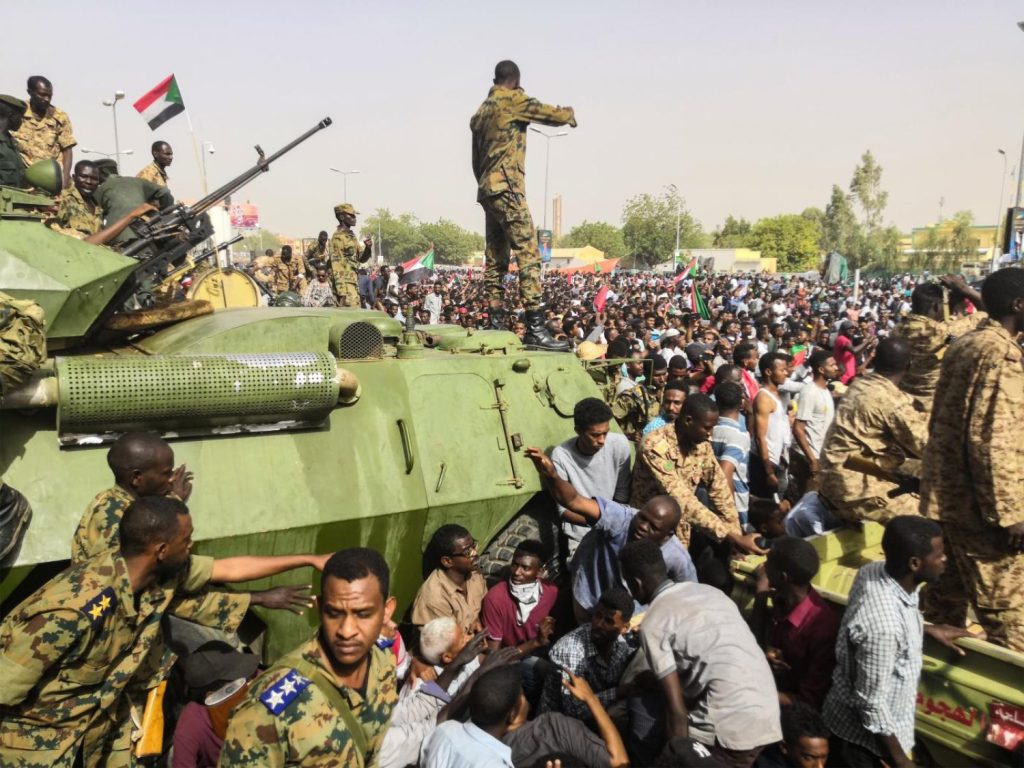

The end of the Cold War saw a new democratic and constitutional trajectory in Africa that brought an end to the post-independence era of military coups and authoritarianism. Africa fought relentlessly against the scourge of coups d’état that spread across the continent soon after independence. The spread of constitutionalism and the deepening of democracy in the 1990s slowed down the occurrence of coups. The events of the past few years, however, indicate a resurgence of military coups on the continent, and that has been disconcerting. The recent coups have been markedly different from the post-independence ones. They are peculiar in that they have been largely supported by the civilian population, especially the youth. This has raised several debates regarding their legitimacy and the future of democracy in Africa. While some have characterised these events as coups d’état, others have opted for the more liberal descriptors such as ‘popular uprisings’ or ‘military-assisted transitions.’1 The cases of Zimbabwe (2017), Mali (2020, 2021), Guinea (2021), Burkina Faso (Jan 2022, Sept 2022), Sudan (2021), Niger (2023), and Gabon (2023) are illustrative. It is important to stress that regardless of the nomenclature one opts for, this form of transition is not provided for in any of these countries’ constitutions.

Given Africa’s history of coups d’état and the aftermath, usually characterised by repression, scholars are at odds trying to explain why civilians would support military regimes. Some scholars have attributed the public support for these coups to general dissatisfaction with democracy.2 Others perceive the public support as a ‘symptom’ of mis-governance by the incumbent (overthrown) regimes.3 All the countries that experienced coups in recent years have constitutions that provide mechanisms for political transitions. Some go as far as limiting presidential terms to ensure that leadership is rotated. It seems, however, that the processes embedded in those constitutions have failed to deliver democratic transitions.

This review aims to examine scholarship on the resurgence of coups d’état, and the conceptual framing of their popular support. We argue that while the popular support for coups does not necessarily symbolise a rejection of democracy, it is a serious indictment on the practice of democracy in Africa.

The legacy of military governments in Africa

History is replete with lessons on coups d’état and military governments. In West Africa, most countries that previously experienced coups in the past are still dealing with the relics of military repression and economic and political instability. Previous coups have been blamed for sowing the seeds of insecurity and the emergence of insurgents and other militia groups. It is difficult to understand how civilians have now turned to the same military as a source of democratic transition. The governance history of countries such as Burkina Faso, Guinea, Liberia, Mali, Niger, Sierra Leone and Togo, among others, shows that those countries have previously experienced coups d’état. However, the military regimes in those countries did not fare any better than the civilian predecessors that they overthrew. Military regimes have also had poor records with respect to corruption, freedom of the press, enforced disappearances, and incarceration without trial for journalists and political opponents. Generally, military regimes have a reputation for impunity, as their human rights violations largely go unchecked.4

Nevertheless, people have supported military coups, despite knowing that a coup may also result in external economic sanctions, state diplomatic isolation, and cuts in external developmental funding, among other things that directly affect the well-being of citizens. Pryce and Time argue, ‘economic hardships within a country may serve as a pretext for soldiers to embark on a coup, even though it is widely known that military regimes have not fared better than their popularly elected counterparts when it comes to reversing a country’s economic ills.’5 Similarly, Chigozie and Oyinmiebi observe:

[…] even more disturbing is the fact that military regimes have more than ever deepened the socio-economic and political crises of these countries in addition to their practice of shrinking space for civil society organisations to thrive, human rights abuses, extrajudicial killings and wanton disregard for the constitution6.

The conceptual complexity of popular coups

On a superficial level, the concept of a coup d’état seems easy to define. However, recent popular coups have been complex, and they do not largely conform to the traditional definitions. Recent coups have been largely bloodless and supported by the population. This has resulted in several distortions in trying to frame them as outright military coups. A coup d’état is defined as ‘a rapid seizure of state power by a small group, usually the military, leading to the overthrow of the existing government.7’ The main feature of this definition is that a coup is usually the work of a minority or small group. That alone may be considered as what distinguishes a coup d’état from a revolution. Singh defines a coup as ‘the sudden and irregular overthrow of an incumbent government, usually with the use of force.8’ Typically, the force referred to here results in the loss of life and other significant human rights violations. Recent coups seem to defy these definitions as they are largely bloodless and free of the characteristic violence. They are also not works of a small group but are supported by the masses. Barbara Walter suggests that a coup is ‘the sudden and illegal overthrow of a government, including executive, legislative, and/or judicial branches, by individuals who command the security forces.’9 This definition does not seem to explain some of the coups where other institutions, such as the legislature and the judiciary, remain intact.

Africa is not new to popular uprisings. The liberation struggles waged against colonialists were popular uprisings. Popular uprisings are usually caused by a trigger event that pushes the wider population to the tipping point. Some result in a change of the political order and some result in certain reforms or demands being met. According to Ani, popular uprisings ‘should have attributes such as non-violence, collective appeal, deep seated concerns, and last resort.’10

Akinola and Makombe attribute the resurgence of coups d’état in Africa to the continent’s inability to institutionalise democracy.11 Ani has observed that ‘in the last decade […], the resurgences of successful popular protests across the continent are indicative of a new trend of protests in Africa – protests that seek to foster democratic consolidation and meaningful development.’12

Economic, social, and security grievances as catalysts for coups

The resurgence of coups, particularly popular coups, has been attributed to weak and, or compromised democratic institutions such as electoral commissions, the judiciary, and the legislature. These are the institutions that have failed to safeguard democracy through the maintenance of their own independence. Incumbents who control these institutions tend to be corrupt, authoritarian and have no respect for the rule of law. These institutions also cannot be trusted to provide democratic means of change of government since elections are often rigged and court decisions are manipulated.13 In Zimbabwe, frequent electoral manipulation and repression led to public support for the military takeover in 2017. In Guinea, when President Alpha Condé amended the Constitution to extend his rule, Guineans were not pleased, and protests broke out, leading to a military takeover in 2021.14 Ani sums this up: ‘while elections have become more common across Africa, authoritarian regimes have adopted fraudulent electoral processes and flawed constitutional amendments to remain in power.’15 These actions rob citizens of their legitimate right to change leadership, and when change comes through a coup, they embrace it. In no uncertain terms, Ani points out that ‘[d]ue to the absence of legitimate channels to ensure change, citizens increasingly rely on extra-democratic approaches for political transition.’ 16

Recent coups have also been influenced by the need to reject family dynasties in some countries. Brossier provides examples of family dynasties: ‘in Togo, Faure Gnassingbe succeeded his father, Gnassingbe Eyadema, who died in 2005; in Gabon, Albert-Bernard Omar Bongo was succeeded by his son Ali in 2009.’17 Both families had been in power since 1967. Ali Bongo was eventually ousted through a coup in 2023.18 In Zimbabwe, there were widespread rumours that Mugabe would hand over power to his wife, Grace.

Most countries in Africa have endured deepened socioeconomic issues that affect the people. As a result, there has been widespread frustration19 with the economic management among citizens. Odigbo, Ezekwulu, and Okeke point out that economic hardship, especially the rising unemployment among the youths, inflation, poverty, and a decline in living standards have triggered widespread frustration. It is this frustration that has culminated in popular support for military coups as citizens view them as a means to remove governments that have failed to deliver on their socioeconomic promises. Opalo argues that weak state institutions have led to weak democratic regimes that cannot improve the economic conditions of their countries. They have failed to provide equal opportunities and basic services hence the deficit in public trust. While Africa is considered one of the richest continents in terms of abundance of resources, the resources have largely been looted or abused by those in power. Those who are marginalised by the inequitable distribution of resources resent the government, and their resentment is used to trigger or justify coups.20

The lack of security against insurgents in the region has also precipitated popular coups. The Burkina Faso coup, led by Captain Ibrahim Traore, was primarily triggered by the general sense of insecurity against the Jihadists in the region. There were widespread concerns over the government’s ability to manage the security crisis in the country. According to reports, at some time during 2021 and 2022, 40% of Burkina Faso had fallen outside the control of government, which was a major cause for concern.21

Rejection of democracy or demand for reform?

Recent events show that coups have received popular support, especially in the Sahel region. This popularity has fundamentally been used to legitimise the coups. The United Nations Development Programme study in Mali in 2022 found that eight in every 10 Malians were in support of the country’s military takeover. According to Ero, ‘this shift in popular opinion appears alarming, suggesting that African citizens are becoming disillusioned with democracy or increasingly believe that authoritarian rule is the only solution to their countries’ problems.’22 This suggests that the people have lost hope in democratic governance in their countries and they believe that the new government would bring change. Scholars suggest that coup supporters hope that the aftermath of the coup will usher in a new democratic trajectory. Some scholars are of the view that military regimes can act as agents of change and set the country on a constitutional and democratic path. Hlongwana submits, ‘certain coups initiate political processes that culminate in restoration of democracy and constitutionalism.’23

It is argued that coup supporters often use their support as a bargaining chip and to teach a lesson to those who harbour dictatorial ambitions. Essentially, they believe that should the new leaders fail to transform their lives and bring democratic change, they will simply support another coup leader to dislodge them. This, however, does not mean that they have no faith in democracy as a concept, but simply have no alternative to bring change using the available democratic tools.

The role of the African Union and ECOWAS

The African Union (AU), like other regional organisations, adopted an anti-coup legal framework. Anti-coup sentiments are echoed in the AU Constitutive Act 2000, the Lomé Declaration on the framework for an Organisation of African Unity (OAU) response to unconstitutional changes of government, as well as the African Charter on Democracy, Elections, and Governance. These instruments, alongside their punitive measures, are adopted specifically to coup-proof Africa. It would also be in the interests of individual member states to condemn coups in other countries and to act in a manner that does not invite coups against themselves. The AU, being a ‘club of incumbents,’ does not always reign in member states who abuse their own citizens through electoral manipulation or an outright crackdown on the opposition. In Sudan, ‘critics accused the AU of not responding to government crackdown but was quick to condemn the military’s role in overthrowing President Omar Al-Bashir.’24

Ramotja and Maphaka argue that ‘despite notable progress in its two-decade existence, persistent governance and security challenges, particularly the resurgence of coups d’état, raise concerns about the AU’s effectiveness in achieving lasting peace and security.’25 The AU has also failed to take a consistent and principled stance against military coups and other human rights violations on the continent. For example, while the AU recognised the popular support of the coup as an expression of the people’s will in Zimbabwe, ‘it condemned the Burkina Faso coup, suspended the country, and threatened to sanction the perpetrators if they failed to restore the Interim Constitution.’26 The AU’s approach to intervention in crises in member states is ‘frosty and contentious.’27 Bamidele submits, ‘the issue of electoral crisis in Africa has created fragile democratic institutions in many African states such as Mali, Cote d’Ivoire, Kenya, Zimbabwe, Nigeria, Central African Republic and many others.’28

The West African regional bloc, the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS), has been the most affected by the recent coups. Scholars Chigozie and Oyinmiebi observe, ‘this resurgence of coups in the region has been implicated in the failure of democracy to be intensified and deepened in West Africa.’29 In dealing with the existential threat caused by coups in the region, ECOWAS has adopted various modalities, including ‘imposition of sanctions, severance of diplomatic relations, suspension of military leaders from the international community,’ among others.30 On the legal front, ECOWAS adopted its Protocol on Democracy and Good Governance in 2001. The instrument provides mechanisms for tackling issues such as military coups, promotion of democratic governance, fair elections, and judicial independence but member states have largely failed to adhere to the instruments.

Post-coup transitions and the imperatives for democratic renewal

It is evident that some of the popular coups are supported by citizens due to their promise to usher in democracy, economic reforms, and security. While it is true that some coups lead to democratisation and economic growth, this is not always the case. Zimbabwe’s coup experience indicates that it is possible for a popular coup to culminate in a more repressive and authoritarian regime. According to Mahuku, ‘many had thought that the post-2017 coup period would usher in a new beginning, a golden era of political order and economic stability.’ The Zimbabwe coup of 2017, widely publicised as a ‘military-led transition,’ was supported by citizens but ‘economic mismanagement and authoritarianism have continued; a worrying phenomenon that has led to military intervention in politics.’ Recent events in the country indicate another volatile situation which may lead to another ‘military-led transition.’ Regardless, the disruptive nature of coups is that they can have the potential to instigate reconstruction and renewal.33 This essentially entails breaking with the past and forging a new future based on new values and principles, including democratic reconstruction.

Conclusion

The resurgence of coups and the popularity that they have received from citizens illustrate widespread disillusionment with the prevailing governance systems in those countries. While others have taken a pessimistic view of democracy and have used the prevalence of popular coups as a sign of rejection of democracy, research shows that popular coups simply represent a crisis of governance. The popularity of coups is a response to the subversion of democratic principles, election rigging, presidential term extensions by incumbents, corruption, weakened institutions, family dynasties, unemployment, and failure to deal with the security situation in the region. The literature reviewed highlights a persistent challenge caused by the failure of democratic institutions to provide mechanisms for peace and legitimate transitions. The literature also highlights the failure of African regional institutions to create robust, accountable, and inclusive democratic systems. These failures have created a conducive environment for military intervention as a vehicle for transition, with popular support.

The interplay between popular coups and legitimate transitions presents a conceptual dilemma. Even though it is evident that popular coups are normally aimed at reforming and preserving popular will, they remain unconstitutional and pose a risk of yet another cycle of coups d’état on the continent. The inconsistency of regional bodies particularly, the AU and ECOWAS, in dealing with coups d’état has undermined efforts to return to constitutionalism and democracy in the region.

Concerted efforts are required to not only condemn coups d’état but to address their root causes. This requires mechanisms to foster economic growth, dismantle political dynasties, substantial reforms to strengthen electoral integrity and rebuild public trust in democracy, among others. It is imperative for scholarship on coups d’état in Africa to begin exploring post-coup trajectories and to consider the role that women, youth, and civil society can play in post-coup rebuilding and renewal.

Funding for this research and the project ‘Coups d’état and the potentials for reconstruction and renewal in Africa’ was provided by SOAS, University of London, under the ISPF-ODA Programme.

Dr Simbarashe Tembo is a Post-Doctoral Researcher in the Nelson R. Mandela, School of Law at the University of Fort Hare.

Dr Laura-Stella Enonchong is a Senior Lecturer at the School of Law, SOAS, University of London.

Endnotes

1Majiga, P. B. (2022) ‘The Proliferation of Popular Protests and Coups d’Etas in Africa’, In Kuwali, D. (Ed.), The Palgrave Handbook of Sustainable Peace and Security in Africa, Cham: Springer International (pp. 181–195).

2Odigbo, J.; Ezekwelu, K. C.; and Okeke, R. C. (2023) ‘Democracy’s discontent and the resurgence of military coups in Africa’, Journal of Contemporary International Relations and Diplomacy , 4(1), 644–655.

3Ero, C. and Mutiga, M. (2024) ‘The Crisis of African Democracy: Coups Are a Symptom – Not the Cause – of Political Dysfunction’, Foreign Affairs, 103(1), 120, 122–134, p. 120.

4Edi, E. (2006) ‘Pan West Africanism and Political Instability in West Africa’, The Journal of Pan African Studies, 1(3), 7–31.

5Pryce, D. K. and Time, V. M. (2023) ‘The role of coups d’état in Africa: why coups occur and their effects on the populace’, International Social Science Journal, 73(250), 1019–1034.

6Chigozie, C. F. and Oyinmiebi, P. T. (2022) ‘Resurgence of military coups in West Africa: implications for ECOWAS’, African Journal of Social Sciences and Humanities Research, 5(2), 52–64.

7Luttwak, E. (1979) Coup d’état: A practical handbook. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

8Singh, N. (2014) Seizing power: The strategic logic of military coups. Baltimore: JHU Press.

9Walter, B., cited in Nwala, P. (2024) ‘Resurgence of coup d’états in African democratic era: is modern democracy a failure or success in Africa?’ ESCAE Journal of Management and Security Studies, 4(2), 15–30.

10Ani, N. C. (2021) ‘Coup or not coup: the African Union and the dilemma of ‘popular uprisings’ in Africa’, Democracy and Security, 17(3), 257–277, p. 265.

11Akinola, A. O. and Makombe, R. (2024) ‘Rethinking the resurgence of military coups in Africa’, Journal of Asian and African Studies, 60(5), 2847–2863.

12Ani, N. C. (2021) ‘Coup or not coup’, op. cit., p. 257.

13Nwala, P. (2024) ‘Resurgence of coup d’états’, op. cit.

14Rosenje, M. O.; Onyebuchi, U. J.; and Adeniyi, O. P. (2022) ‘Tenure elongation and democratic consolidation in Africa: lessons from the 2021 coup d’état in Guinea’, Benue Journal of Peace and Conflict Studies, 1(1), pp. 253–272.

15Ani, N. C. (2021) ‘Coup or not coup’, op. cit., p. 258.

16Ibid.

17Brossier, M. (2024) ‘Succession in personalist regimes in Africa: Dynastic Options in Gabon and Togo’, In: Baturo, A.; Anceschi, L.; Cavatorta, F. (Eds), Personalism and Personalist Regimes, Oxon: Oxford University Press (pp. 231–251), p. 231.

18Battera, F. (2023) ‘Who holds the power? Political succession and authoritarian regimes in Africa (1990-2020)’, Nuovi Autoritarismi e Democrazie: Diritto, Istituzioni, Società, 5(2), 137–157.

19Odigbo, J. et al. (2023) ‘Democracy’s discontent’, op. cit.

20Pryce, D. K. and Time, V. M. (2023) ‘The role of coups d’état’, op cit.

21Al Jazeera (2022) “State controls just 60 percent of Burkina Faso: ECOWAS mediator”, Available at https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2022/6/18/state-controls-only-60-percent-of-burkina-faso-mediator (Accessed 09 October 2025)

22Ero, C. and Mutiga, M. (2024) ‘The Crisis of African Democracy’, op. cit.

23Hlongwana, J. (2018) ‘A celebrated coup that appear like not a coup? The fall of Robert Mugabe in the context of Zimbabwean and regional politics’, In Mawere, M.; Marongwe, N.; and Duri, P. T. (Eds), The end of an era? Robert Mugabe and a conflicting legacy, Bemenda: Langaa Research and Publishing CIG, p. 95.

24Ani, N. C. (2021) ‘Coup or not coup’, op. cit., p. 259.

25Ramontja, N. and Maphaka D. (2024) ‘The Resurgence of Coups d’états in Africa and the Role of the African Union and Civil Society Organisations’, Journal of African Union Studies, 13(1), 67–82, p. 67.

26Ibid.

27Bamidele, S. (2017) ‘Regional approaches to crisis response, the African Union (AU) intervention in African states: How viable is it?’ India Quarterly, 73(1), 114–128, p. 116.

28Ibid.

29Chigozie, C. F. and Oyinmiebi, P. T. (2022) ‘Resurgence of military coups’, op. cit.

30Ibid, p. 53.

31Williams, C. D and Sunjo, E. (2024) ‘Evaluating the Effectiveness of the ECOWAS Protocol on Democracy and Good Governance in Preventing the Resurgence of Military Coups in West Africa’, International Journal of Research and Innovation in Social Science, 8(1), 255–264.

32Fabricius, P. (2025) ‘Is Zimbabwe facing another November 2017?’ Institute for Security Studies, 28 March, Available at: https://issafrica.org/iss-today/is-zimbabwe-facing-another-november-2017 (09 October 2025).

33Enonchong, L.-S. (Forthcoming) ‘The return of coup d’etat’, In: Daly, T. G. and Dziedzic, A. (Eds), Research Handbook on Constitutions and Democracies, Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.