Abstract

The continued threat of insurgency in Mozambique has triggered academic and policy interest in the recent past. Indeed, the ramifications caused by acts of insurgency globally and in Africa remain endemic. This calls for the need to establish sustainable and context-specific interventions at regional and national levels. The Common Market of Eastern and Southern Africa (COMESA) and the Southern African Development Community (SADC) regions have not been spared from the lethality of insurgency, with Mozambique morphing into the epicentre of interest. Insurgency has caused untold suffering to communities in Mozambique’s Cabo Delgado province, prompting the deployment of a SADC mission. As a regional peace operation, the SADC Mission in Mozambique (SAMIM) was deployed on 15 July 2021 following approval by the Extraordinary SADC Summit of Heads of State and Government held in Maputo, Mozambique on 23 June 2021. The main objective of SAMIM was to support the Republic of Mozambique to combat armed groups and acts of insurgency, particularly in the Cabo Delgado province. This article seeks to understand the impact of the SAMIM intervention. It mainly interrogates SAMIM’s mandate, structure, success, challenges and lessons learned using both qualitative and quantitative research methodologies and various open data sources, including programmatic documents.

Key words: SADC, insurgency, peacekeeping, security, Cabo Delgado

1. Introduction

The [re]construction and consolidation of the state in Africa continues to face a myriad of challenges (Khadiagala, 2015). More importantly are the security related challenges that have been complicated by the proliferation of small arms and light weapons, and the emergence of mercenary and insurgency groups. While there have been efforts at continental, regional and national levels to deal with the emerging security challenges, they continue to manifest with serious ramification and spillover effects on the various sectors of society. In some cases, they have threatened the very existence of the state itself. In this context, one of the security threats that continues to attract both policy and academic interest, and forms the nub of this article, is insurgency that manifests in terrorist acts. According to the Africa Centre for the Study and Research on Terrorism (ACSRT), the number of insurgency attacks and victims of insurgency/terrorism have both multiplied in the past decade (ACSRT, 2023:3). Between 2017 and 2022, for instance, ACSRT recorded approximately 10 000 attacks that resulted in over 40 000 deaths (ACSRT, 2023:3). In the first half of 2023, ACSRT had recorded 1500 attacks and approximately 8500 deaths. This represents an approximate 94% increase in attacks and almost 37% increase in deaths when compared to same period in 2022 (ACSRT, 2023:3).

Insurgency remains a concern in the COMESA region, particularly in its member states of Uganda, Somalia and Kenya, which have especially continued to experience sporadic attacks by Al-shabaab. Boko Haram and its remnants continue to cause havoc in West Africa (Niger, Nigeria, Mali and Burkina Faso). In the north, the Islamic state continues to destabilise Libya and is actively involved in the Sinai Peninsula, although the number of attacks has reduced significantly in these regions. Emerging trends of insurgency/terrorist attacks in the above highlighted region include (1) the proliferation of the number of insurgency groups, (2) the existence of foreign intervention to contain the menace, (3) the sophistication and lethality of the attacks, (4) the geographical spread of insurgency acts and groups and (5) the centrality of technology and the increasing use of the cyber space (see for example Otiso, 2009:109). The SADC region has not been spared of the malady – it has become the focus with a spread of violent extremism and insurgency activities in Mozambique (Bussotti and Coimbra, 2023). While for a long time the SADC region was generally immune to acts of terror and violent extremism, the threats have been looming, especially with the proliferation of insurgency groups1The groups that operate or have operated in Africa include, inter alia, Boko Haram, Al Qaida in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM), Almourabitoun, Islamic State in West Africa Province (ISWAP), Macina Liberation Front (MLF), Jama’a Nusrat ul-Islam wa al-Muslimin (JNIM), Islamic State (IS), Al Shabaab in the Horn of Africa, Islamic State in Central Africa Province (ISCAP), Allied Democratic Forces (ADF),and the Al Sunnah waJama’ah (ASWJ) on the continent.

The spread of insurgency attacks and the continued violent extremism, especially in Cabo Delgado province in Mozambique, prompted a strategic intervention from SADC (Mandigo et al., 2023). On 19 May 2020, during the SADC Extraordinary Organ Troika Summit of Heads of State and Government, Mozambique made a formal request to SADC for support to fight the Islamic insurgency that was spreading in Cabo Delgado province (Vhumbunu, 2021). As a response to the request, on 15 July 2021 SADC deployed the SADC Mission in Mozambique (SAMIM).

This article seeks to interrogate SAMIM and answer the following questions: How was SAMIM structured? How was this mission different from the other missions that SADC had deployed in the region? What were the limitations of the mission and what were the lessons learned as it relates to combating insurgency acts in the region? The article makes use of secondary data gathered through mission reports, policy papers, journal articles and communiques on the subject area. The next section provides the historical context of terrorism in the SADC region with a focus on Mozambique, it then looks at the impact of terrorism in the SADC region, interrogates in detail SAMIM’s modus operandi and finally highlights some of the lessons learned from SADC engagement in Mozambique. The last part concludes the article.

2. Tracing the genesis of insurgency and violent extremism in Mozambique

From the onset, it is imperative to debunk the concept of insurgency and its relationship to terrorism. Several definitions have been proffered that outline the different aspects or understanding of the concept. The concept has predominantly been conceptualised from two perspectives. On the one hand, the concept has been associated with rebellion against a government or civilian authority. On the other hand, it has been construed in terms of strategy or tactics (see Anum, 2017:20). Jones (2008) defines insurgency as “a political-military campaign by nonstate [sic] actors who seek to overthrow a government or secede from a country through the use of unconventional – and sometimes conventional – military strategies and tactics”. To Wilkinson (2001), the concept denotes a rebellion or uprising against a government. As a strategy, insurgency is viewed as an organised military struggle geared towards delegitimising a government or a struggle that is methodically organised to achieve a specific goal (Galula, 1964; see US Army, 2007). As a concept, insurgency is multidimensional, and it entails both the desire to gain power or control and the use of terror. As a strategy, it denotes the use of force to attain a certain goal.

Based on the above conceptualisation, two typologies of insurgency have been discussed in academic literature. The first type is the classical or what has been referred to as the traditional insurgency. This typology of insurgency was influenced by the events of the post-World War II era. During this epoch, insurgency had a nationalistic outlook and was more transnational – it was synonymous with revolutionary warfare. Its objective was to overthrow external occupiers, dethrone colonialism and overthrow what was considered illegitimate regimes. According to Anum (2017:26), “the period also witnessed the proliferation of wars, conducted mainly by the proxies of the Cold War superpowers”.

The second typology, which connotes the modern or contemporary form of insurgency, is associated with popular uprising or urban insurrections. This typology of insurgency is mainly motivated by cultural undertones, ideologies, greed, religious extremism, ethno-nationalism or economic-oriented grievances. The contemporary period has been characterised by the rise of jihadism, perpetuated by Al-Qaeda and other groups, and the use of terror. In a cursory review of the Taliban in Afghanistan, for example, Jones (2009:19) observes that the Taliban insurgency is motivated by radical ideology based on an “interpretation of Sunni Islam derived from Deobandism”. He avers that “the Taliban desire a control over Afghanistan due to religious and ideological reasons, and this is where insurgency in Afghanistan becomes extremely difficult to address” (Jones, 2015:11). The insurgency in Mozambique falls within the ambit of the second typology.

Matsinhe and Valoi (2019) associate the origin of insurgency in Mozambique to intermittent attacks on police stations in the town of Mocímboa da Praia of Cabo Delgado province in October 2017. The attacks were mainly orchestrated by a clandestine group identified as the Ansar al-Sunna (Vhumbunu, 2021), who stage-managed sporadic and deadly attacks against civilians in the villages and towns. Locally, the group is known as the al-Shabaab; however, there is little linkage with the al-Shabaab group that is predominantly domiciled in Somalia (Zamfir, 2021). Despite the lack of a clear connection, the group seems to have the same goal as the al-Shabaab in Somalia – it seeks to establish an Islamic state in this region of Mozambique, much to chagrin of the local citizens (see, for example, Klobucista et al., 2021).

In terms of structure, the Ansar al-Sunna or al-Shabaab terrorist group of Mozambique has a rudimentary structure that is made up of lower-level militants who are largely Mozambicans – predominantly young men of Mwani and Makua origin. They are mainly former fishermen and farmers, coastal smugglers and traders, or unemployed youth (International Crisis Group, 2021). According to Langa (2021), the group lays claim to the fact that it has fraternal ties with the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS). This assertion is in tandem with Neethling’s perspective that the Ansar al-Sunna Islamist group draws its inspiration and legitimate linkage from international Islamist groups – the ISIS whom the group pledges allegiance to with its ideal of establishing a caliphate (Neethling, 2021). It can be argued further that the proliferation of insurgency in Cabo Delgado province has been given impetus by a plethora of factors that dovetail with religious, social, economic, political, cultural and economic factors that provided the fertile ground for the insurgency to sprout. According to various sources (see, for example, Faria, 2021), the cardinal objective of the al-Shabaab insurgent group of Mozambique is to establish a political order inspired by the principles of Sharia law by capitalising on Mozambique’s vulnerabilities, which include poor public service delivery, unemployment, endemic corruption and proliferation of foreign jihadists who are propagating mass radicalisation.

Geographically, the insurgent group has been orchestrating targeted attacks mainly in five isolated and coastal districts: Mocímboa da Praia, Palma, Macomia, Nangade and Quissanga (Matsinhe and Valoi, 2019). The attacks have resulted in a rise in the death toll. The United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (UNOCHA) (2020) estimated that a total of 2400 people were killed and another 500 000 displaced between 2017 and 2020. While the Mocímboa da Praia district is the hometown of this insurgent group, the group’s terror attacks are more prominent in Macomia district (Matsinhe and Valoi, 2019).

As the insurgency and the Mozambican conflict continue to escalate, mostly targeting innocent civilians, public infrastructure and government installations, the government of Mozambique also continues to make concerted efforts towards subduing and ending the insurgency through its national defence forces – the Forças Armadas de Defesa de Moçambique (FADM) (Vhumbunu, 2021), with the support of international military from the SADC region and Rwandan troops (Louw-Vaudran, 2022; Makonye, 2022). The government forces have engaged in a series of battles with the Ansar al-Sunna terrorist group, which have resulted in widespread violence and insecurity in the province.

2.1 Underlying drivers of insurgency in Cabo Delgado province

As alluded to above, the rise of insurgency in Mozambique, particularly in the province of Cabo Delgado, is correlated with terrorism acts, whose drivers are too complex and too numerous to examine. The complexity is compounded by the province’s historical, economic, social and political factors that have undermined the regional security system in the SADC region (Obaji, 2021; Sidumo et al., 2024). Therefore, the analysis of the drivers of terrorism elucidated in this article is not by any chance exhaustive but sufficient to provide a nuanced understanding of the context and the prevailing situation.

To start with, it is apt to argue that the drivers of insurgency and terrorist attacks in Cabo Delgado province are to a larger extent associated with Mozambique’s historical antecedent. Since independence in 1975, Cabo Delgado province has remained marginalised and poor when compared to the other provinces. This situation was exacerbated by the civil war between the Liberation Front of Mozambique (FRELIMO) government and National Resistance Movement of Mozambique (RENAMO) insurgents (Alden and Chichava, 2021). Premised on these historical realities, it is not in vain to create a link between the scar of the civil wars and the emerging realities and trends in Cabo Delgado province. It can be further argued that the historical marginalisation (real or perceived) has, to some extent, triggered a feeling of disillusionment among the indigent population, thus driving them to join the group that seems to promise a ‘grandiose and glamourous lifestyle’ free of suffering and control.

The second inherent driver of the insurgency is poverty. While it has been argued that there is no causal connection between poverty and insurgency/terrorism (for example, Piehl, 1998; Ruhm, 2000), it is possible that poverty is associated with illegal or criminal activities that include terrorism. A study conducted by the World Bank between 2016 and 2018 indicated that there was a causal connection between terrorism and poverty (De Silva, 2017). According to this study, terrorism has had an impact on household income and poverty levels. This scenario has pushed a cross section of the population, but especially the youth, to join al-Shaabab (Nunez-Chaim and Pape, 2022). In the case of Cabo Delgado, it can be argued that the high levels of poverty act as a push factor for the ongoing insurgency. The province is one of the poorest and household poverty is rife. In fact, the province is the second poorest of all Mozambique’s provinces, a situation that exacerbates polarisation in this northern region of Mozambique (Alden and Chichava, 2021). Evidence indicates that the lack of government presence coupled with military and police brutality, and oppression of the impecunious population, has further compounded the problem (Amnesty International, 2021).

The third driver of the insurgency stems from Cabo Delgado’s significant resource endowment. Bissada (2020:2) avers that “the violence in Cabo Delgado erupted several years ago as companies discovered massive oil and gas deposits in the region”. Bissada’s postulation is in tandem with the resource curse thesis which is grounded on the argument that resource abundance in some contexts (especially in Africa) drives conflict. The underlying argument here is that the discovery of oil and gas has given impetus to the emergence of the terror group for access and control.

Fourth, the Islamic ideology as a global phenomenon has given some impetus to the rise of the insurgency in the Cabo Delgado province. Radical Islamic ideology, which is fast growing in Mozambique, is essentially in conflict with the western ideology or other religious manifestations (United States Institute of Peace, 2002). As alluded to above, the province constitutes majority ethnic extracts, including the Mwani and the Makwe speakers who practice Islam. These associated communities have launched numerous attacks, for example in Mogovolas. Many other attacks launched in Mocímboa da Praia are associated with an Islamic oriented group linked to Ansar al-sunna, who are believed to have been seeking to gain control of the town and install their version of law and order (Matsinhe and Valoi, 2019). This is a clear demonstration of the struggle for Islamic dominance. This struggle for Islamic popularisation against other sets of religious orientation has become a global phenomenon that has manifested across the province of Cabo Delgado and extends to other regions of the African continent (Steinberg and Weber, 2015).

At the global level, western ideology is perceived as a more inclusive governance system. However, its principles are in constant conflict with Islamic ideology (Steinberg and Weber, 2015). By default, any regime that does not subscribe to a western doctrine and its principles joins the quiet revolution of Islam’s search for world dominance. Recent studies show that terror attacks across many regions, including Africa, are increasingly perpetrated on the basis of Islamic dominance (Gberie, 2016). There is an underlying perception that the protection of Islamic ideology and identity from dilution is deemed as a religious duty for the Muslims. Therefore, any form of aggression against Islam becomes the breeding ground for acts of terrorism in an effort to preserve the indigenousness of the Islamic system (Ibrahim, 2017). This ideally explains the drivers of terrorism, extremism and jihadism in most parts of the world, which is also spreading rapidly to other regions of the world. Therefore, it is not surprising that Islamic oriented terror insurgencies are gaining a grip in Cabo Delgado, in particular, and in Mozambique at large.

Fifth, combined with the appetite for Islamic dominance, the scarcity of employment among the youthful population in the Cabo Delgado province has strongly been associated with acts of terror (Alden and Chichava, 2021). Certainly, the high level of unemployment among the youths in Mozambique, which is more experienced in Cabo Delgado, accelerates the province’s vulnerability to terrorism. This situation has created an open vacuum for recruitment. Moreover, the majority of the population in the province relies on subsistence agriculture as the primary source of livelihood with few opportunities outside this sector (Alden and Chichava, 2021). The plight of unemployment among the youthful population in the province has created serious levels of economic desperation among the unemployed and discontent among the youth. Ultimately, this provides a fertile ground for recruitment (Adelaja and George, 2020).

Undoubtedly, the high level of unemployment has increasingly become fertile ground for youth radicalisation, with the majority young people claiming that the few jobs in the growing oil and natural gas extraction industry located within the province are indiscriminately reserved for people outside Cabo Delgado province, especially those from the urban Maputo, Mozambique’s capital (Matsinhe and Valoi, 2019). In summation, the Cabo Delgado’s al-Shabaab or Ansar al-Sunna insurgency has exploited the ‘youth unemployment vacuum’ and the province’s rampant inequality for recruitment, radicalisation and expansion. This has enabled it to advance its terror objectives within the province, much to the chagrin of the local indigent population.

Sixth, marginalisation and exclusion is closely associated with the insurgency in Cabo Delgado. In their study captioned, ‘The Genesis of Insurgence in Northern Mozambique’, Matsinhe and Valoi (2019) assert that social exclusion and marginalisation in Cabo Delgado appear to be one of the root causes of the terror attacks in the province (Matsinhe and Valoi, 2019). According to the socio-economic analysis conducted by Neethling (2021), the vast majority of the population, particularly the young people in the Cabo Delgado province, feel marginalised and socially excluded from Mozambique’s economic affairs. Since the country’s independence, Cabo Delgado province has suffered endemic poverty coupled with the poorest social services, such as health, education and sanitation facilities, making it a forgotten and bottom-ranked province of Mozambique (Neethling, 2021). Some observers further argue that these conditions have led to many community members, who lack proper education and formal employment, to sympathise with and facilitate insurgent recruitment (ACAPS, 2020).

Lastly, corruption is another phenomenon driving terrorism in Cabo Delgado province. With corruption being endemic in most African states, Mozambique inclusive, many terrorists or extremist groups find it easy to mobilise and ride on corruption infiltrated systems. Campbell (2020) argues that the insurgency in Cabo Delgado province has been associated with a mixture of domestic factors, such as marginalisation, neglect and institutionalised corruption that is widespread and imposed by successive FRELIMO governments (Faria, 2021). Practitioners argue that research is gradually emerging which depicts the nexus between corruption and terrorism at local and regional levels (UNDP, 2020). This is also recognised in international resolutions such as the UN Secretary General’s Plan of Action on Preventing Violent Extremism (United Nations, 2015). The Plan of Action clearly suggests that acts of terrorism are prominent in countries with high corruption levels. However, corruption by itself cannot be a factor in absolute terms and for this link to be made, it has to cross-fertilise with other factors such as poverty, marginalisation, exclusion, breakdown of the rule of law and weak state institutions.

It goes without rhetoric that the mere presence of an active Ansar al-Sunna insurgency in Mozambique has threatened not only the security of Mozambique but also neighbouring countries with no history of terrorism. Countries such as South Africa, Zambia and Tanzania continue to suffer the spillover effects owing to their proximity to the terror-prone Mozambique, especially as a result of increased globalisation (Gunaratna, 2008). The cross-border effects manifest in numerous ways, including increased refugee flows into Tanzania and other surrounding countries, and socio-economic impacts. The push factors for these forced movements of people across international borders have been worsened by the sophistication and employment of a spectrum of methods of war, for example, the indiscriminate targeting and kidnapping of civilians. The Ansar al-Sunna terrorist group in Mozambique is gaining regional recognition within the SADC region, especially with their established links with international terrorist groups such as ISIS.

3. SADC interventions through SAMIM

SADC has a history of intervening in its member states when political crises and situations of insecurity arise. This is always conducted in line with the Protocol on Politics, Defence and Security Co-operation (2001) and the SADC Mutual Defence Pact, adopted in 2003, thus making the recent SADC footprint in Mozambique not so novel. Nevertheless, according to Chingotuane et al. (2021), SADC’s decision to intervene in Mozambique was characterised by political hesitation. While SADC’s Organ for Politics, Defence and Security had met severally to deliberate on the situation, the decision to intervene was made much later. Dzinesa (2023) notes that, since 2020, several preparatory meetings, including the convening of an extraordinary meeting of the Troika Organ Summit, were held and attended by several Heads of State. It has been argued that the delay in deciding and the delays that characterised the mission’s preparatory stage, which ultimately delayed SADC’s response to the situation, created room for the insurgents to gain more ground in Cabo Delgado (Morier-Genoud, 2020). Sithole (2022) indicates that while SADC was deliberating and preparing for deployment, the Islamic insurgents continued to undertake more sophisticated attacks and further acquired more territorial control.

On 23 June 2021, the SADC Extraordinary Summit of Heads of State and Government finally decided to deploy SAMIM on 15 July 2021 as a regional response to support the Republic of Mozambique in dealing with the terror in Cabo Delgado. Also, the mission aimed to create a buffer zone that would see softer and more comprehensive interventions being undertaken to address the humanitarian dimension of the crisis. It is imperative to note that SAMIM falls within SADC’s regional Defence Pact which allows the military to intervene in crises and prevent the spread of armed conflict (Bolani, 2021). Following this decision, SADC approved an allocation of US$ 12 million to help SAMIM gain ground in the Cabo Delgado province (Chingotuane et al., 2021). However, with the trajectories of events in the province, the allocation was insufficient to produce the desired outcomes in the short term.

3.1 SAMIM’s deployment mandate

SAMIM’s mandate included supporting the Republic of Mozambique to fight the insurgency and acts of violent extremism in the Cabo Delgado province by mollifying the insurgency threat and restoring stability, and strengthening and maintaining peace and security in the region. In addition, SAMIM endeavoured to foster restoration of law and order in affected areas of Cabo Delgado province and support the host country, in collaboration with humanitarian agencies, to provide humanitarian relief to civilian populations affected by the conflict. In its operation, SAMIM was supported by the Regional Coordination Mechanism (RCM) that reported to the Head of Mission and the SADC Executive Secretary (SADC, 2021).

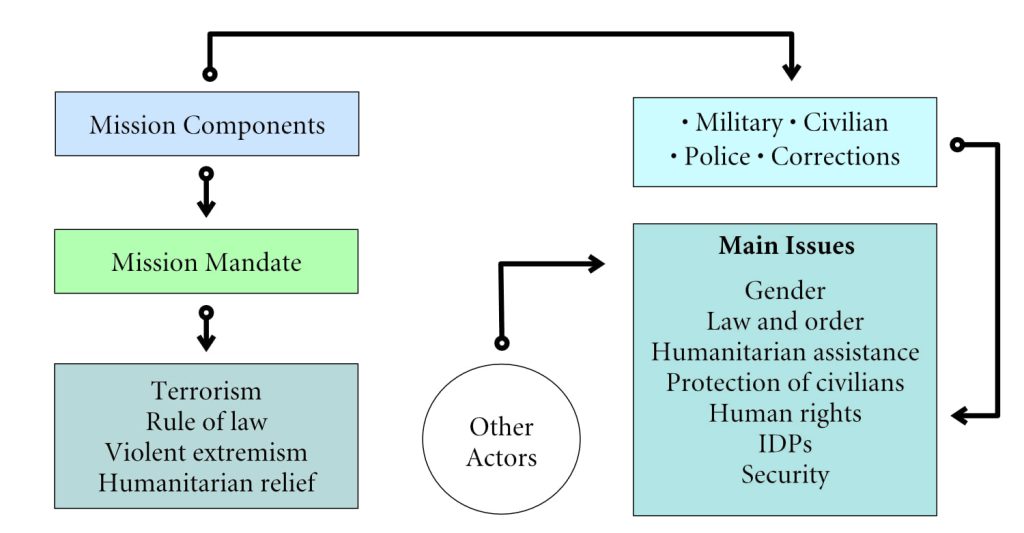

The mission was comprised of military, civilian, police and correctional components. Combined, these components worked on various and complex issues ranging from security, rule of law, gender, protection of civilians, delivery of humanitarian assistance and other critical areas. In terms of composition, the military component stood at approximately 2249 troops, mainly from Angola, Botswana, Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), Lesotho, Malawi, South Africa, United Republic of Tanzania, Zambia and Zimbabwe. They worked in collaboration with the Mozambican army to support the stabilisation and pacification of Cabo Delgado province (SADC, 2021).

| Troop Country | Strength of troops | Date Deployed | Military type | Host |

| Angola | 20 | August 2021 | Military Operations | SAMIM |

| Lesotho | 70 | August 2021 | Military Operations | SAMIM |

| Botswana | 400 | August 2021 | Military Operations | SAMIM |

| Tanzania | 277 | August 2021 | Military Operations | SAMIM |

| Zambia | 50 (Zambia Airforce) | August 2021 | Air wing/logistics | SAMIM |

| South Africa | +/- 1450 (against 1495 planned) | August 2021 | Military Operations | SAMIM |

| Zimbabwe | 1 | August 2021 | Military Expert | SAMIM |

| Malawi | 1 | August 2021 | Military Expert | SAMIM |

An analysis of SADC’s deployment documents further indicated that the civilian component had 13 experts, 20 police personnel and two corrections officers deployed in the mission. With this data, many questions abound including to what extent the mission was able to facilitate stabilisation and pacification of the Cabo Delgado province and had the mission prioritised military intervention over other objectives. A cursory review of the mission documents (SADC, 2021) further indicated that SAMIM transitioned from Scenario six2Scenario six emphasises operations through rapid deployment of military approaches, Scenario five focuses on a multidimensional approach, combining operations of military, civilian, police and correctional services components. The scenarios are drawn from African Union Peace Support Operations (AU PSO) frameworks. (rapid deployment of the military forces) to Scenario five (multidimensional mission) in 2021. Practically, this meant a shift in scope from being a pure military operation to a multidimensional mission that incorporated integrated efforts to respond to a wide spectrum of issues such as security, human rights, gender, humanitarian stabilisation and other non-military threats in Cabo Delgado province (Mandigo et al., 2023). The inclusion of the corrections services in a multidimensional context was a new approach and entailed the clear ambitions of SADC to contribute to peace and security in Cabo Delgado in the long term by addressing the structural factors. Despite this move, there was no increase in the number of civilians, police and correctional services to accompany the transition.

While SADC prides itself as having regional capabilities to respond to insurgency or terrorism as espoused in its counter-terrorism strategy developed in 2015 (Chingotuane et al., 2021), it can be argued that there were serious inadequacies on many fronts. First, the mission’s civilian component was small in number and scope to respond to complex issues of a political, social, legal or humanitarian nature. Second, history has demonstrated that military approaches to insurgency/counter-terrorism are weak and not likely to produce sustainable solutions to the crisis (Ugwueze and Onuoha, 2020). Figure 1 shows the mandate, mission components and wide range of issues which the mission intended to address operating under Scenario five.

A cursory review of the SAMIM military component (size, logistics, mobility issues and preparedness) indicated that it was ill-prepared to adequately respond to threats of terror and violent extremism confronting Cabo Delgado (Domson-Lindsay, 2022). In other words, the military was unable to handle the existing defence and security issues in Cabo Delgado province. Without a secure environment, it was difficult to address numerous vulnerabilities in Cabo Delgado, including food security, distribution, access to social and other human security needs. In addition, with lower budgets to cater for the military needs, the military struggled to restore or maintain domestic law and order by itself. These factors point to the fact that the mission was structurally handicapped and could not effectively fulfil its mandate.

3.2 Legal frameworks underpinning SADC intervention in Mozambique

A critical analysis of the SADC position on maintaining peace and security shows that the regional body has at its disposal several legal frameworks, in addition to a number of institutions and structures to facilitate its intervention in any of its member states (Vhumbunu, 2021). As alluded to above, SADC’s security intervention was mainly informed by the SADC Treaty (1992), the SADC Protocol on Politics, Defence and Security cooperation (2001), the SADC Common Agenda (as amended in 2009) and the SADC Mutual Defence Pact, 2003. In terms of policy frameworks, SADC has formulated the SADC Counter Terrorism Strategy of 2015 and the harmonised Strategic Indicative Plan for the Organ on Defence, Politics and Security (SIPO). According to Van Nieuwkerk (2013), the main objective of these policy frameworks is to create a peaceful, stable political and security atmosphere through which SADC would realise its socio-economic agenda. The SIPO is a key instrument for the operationalisation of the Protocol on Politics, Defence and Security Cooperation of 2001. This Protocol is anchored in the Common Agenda of SADC as reflected in Article 5 of the SADC Treaty. In terms of structures, SADC is supported by the Summit of Heads of States or Government; Organ on Politics, Defence and Security Cooperation (OPDSC); the Troika3SADC Troika is a decision-making governance structure that focuses on political, defence and security matters within SADC. and the Council of Ministers.

Vhumbunu (2021) notes that the SADC intervention in Mozambique was informed by the above legal frameworks and supported by the institutional structures. Literature shows that the Mozambique government requested assistance and support from SADC member states to address the insurgency in Cabo Delgado province (Vhumbunu, 2021). This request was made in line with the procedures provided for under the SADC legal instruments, particularly Article 11(4) of the SADC Protocol on Politics, Defence and Security. According to Vhumbunu, (2021), Mozambique was requested by the SADC Summit to prepare and submit for consideration, by SADC Inter-State Defence and Security Committee, a roadmap for addressing instabilities caused by the insurgency in Cabo Delgado province.

SADC’s homegrown instruments are augmented by the African Union (AU) legal and normative instruments. As such, SADC intervention in Mozambique was anchored in the existing AU instruments that underpinned the peace and security agenda (Engel, 2023). Examples of these legal frameworks include the 1992 Organization of African Unity (OAU) Resolution on the Strengthening of Cooperation and Coordination among African States; the 1994 OAU Declaration on the Code of Conduct for Inter-African Relations; 2002 AU Plan of Action for the Prevention and Combating of Terrorism; the 1999 OAU Convention on the Prevention and Combating of Terrorism and the 2004 AU Protocol to the Convention on the Prevention and Combating of Terrorism. It is necessary to mention that the 1999 OAU Convention on the Prevention and Combating of Terrorism and the 2004 AU Protocol inform the interventions that specifically relate to countering violent extremism and terrorism at continental, regional and national levels. These frameworks notwithstanding, their domestication, ratification and operationalisation remain a challenge.

4. Achievements, challenges and lessons in SADC’s intervention in Mozambique

Anecdotal evidence from Mozambique indicates that some positives were registered by SAMIM. The mission had reclaimed and pacified villages and towns previously occupied by the insurgency group. These areas included Macomia, Mocímboa da Praia and Palma. SAMIM further dislodged the insurgency group from its bases and seized weapons and other warfare materials. This contributed to the creation of a relatively secure environment for safer passage of humanitarian support and it brought the situation to normalcy. The mission also facilitated the return of internally displaced persons (IDPs) to their homes. In tandem with its successes, SAMIM also encountered several challenges, including the following:

- Internal challenges relating to transitioning from Scenario six to Scenario five. The transition from Scenario six, the emphasis of which was on military operations to end the violence, to Scenario five, the focus of which was on a multidimensional context that complemented military operations, posed a challenge. Under scenario five, SAMIM proposed to increase the deployment of the civilian, police and correctional services components to respond to security, human rights, gender, humanitarian stabilisation and other non-military threats in Cabo Delgado province. The deployment of the personnel under Scenario five was not realised by the time the mission was withdrawn from Cabo Delgado.

- The mission also faced financial challenges that impacted on its operations. While the mission’s mandate was clear, the full realisation of this mandate was impeded by inadequate resources to adequately fund various mission functions. This resulted in the personnel contributing countries (PCCs) resorting to meeting their own expenses (Deleglise, 2021). Insufficient funding created numerous operational gaps and shortfalls.

- Non-cooperation between actors remained a notable challenge. Coordination among SADC member states and other regional actors also remained a challenge. According to Ballard (2022), different countries had varying levels of commitment and capacity to contribute to combating the insurgency, which led to a lack of synergy in their efforts. Also, the weak coordination among stakeholders created operational gaps that worked in favour of the insurgent group, ultimately undermining the protection of civilians, and increasing humanitarian risks. Further, Ballard (2022) argues that the operational coordination between counter-insurgent forces on the ground appeared to be inconsistent, which further weakened the operational capacity of the forces.

- The amorphous nature and the changing tactics of the insurgent group were another challenge that SAMIM faced. Following the deployment of a more robust counter-terrorism force that included SAMIM and Rwanda forces (Cascais, 2021), the group were compelled to employ clandestine strategies – splitting into smaller, more mobile units and shifting into areas that provided them with easy prey to further their objectives. The group continued to employ guerrilla warfare, concentrating on attacking easy targets such as civilian installations and villages, rather than attempting to hold territory as it had done previously. Their geographical area familiarity and their ability to exploit gaps among Rwandan, SAMIM and Mozambican forces helped the group to rebound and adapt (Columbo, 2023). In the same line, Yussuf (2023) observes that the group positioned themselves as a community group with objectives consistent with the community’s expectations and aspirations. This strengthened their efforts in building relations with the civilians, giving itself a messianic outlook and portraying itself as an ally to the general public rather than as an enemy.

- The exclusive military approach to combating terrorism remained a concern: there was more focus on military tactics to address the insurgency, particularly by the Mozambican army. While this approach is viewed as helpful, its sustainability is questionable, especially in the face of numerous non-military sources of conflict. We argue that military approaches should be preceded by more balanced counter-terrorism strategies that would address the underlying social, economic and political grievances that drive this conflict in Cabo Delgado (Columbo, 2023).

Several lessons can be deduced from SADC’s intervention in Mozambique. First, SADC should have explored additional avenues of resource mobilisation to support the intervention. SAMIM experienced logistic and financial challenges that hindered the mission from effectively discharging its mandate. The support also included building the operational capacity of the Mozambican defence and security forces in the fight against terrorism and violent extremism (DefenceWeb, 2022). The use of the AU Peace Fund could be experimented with in the Mozambican situation, thus contributing to the realisation of the notion of ‘African Solutions to African Problems, with African Resources’.

Second, there is need for the government of Mozambique and other actors in the theatre to address historical grievances. Observers to the conflict in Cabo Delgabo have highlighted the underlying structural factors that are driving the conflict and that continue to undermine the security situation in Cabo Delgabo. The failure of the government to deliver the ‘political kingdom’ has further exacerbated the situation. As alluded to, the declining humanitarian conditions and worsening economic conditions continue to feed into pre-existing grievances against the government. This increases the urgent need for a more balanced approach by the government and other actors that will also address the local drivers of the conflict (Sheehy, 2021). A 2023 United Nations Development Program (UNDP) study of jihadism in Africa identified the lack of employment and the need for income as the reasons why some youths joined a jihadi group. Furthermore, nearly half of those that took part in the study noted that they joined in reaction to a ‘trigger event’ that more often than not involved government abuse toward themselves or a loved one (UNDP, 2023). Therefore, the need to address the root causes (as discussed above) is imperative and timely.

Third, perceptions of biased security provision should be addressed. There is a growing perception from the local indigent population that the government is selective in its provision of security. In fact, the disconnect between official government statements about security in the province and the events unfolding on the ground have given impetus to these perceptions. The imbalance in the government’s approach to the conflict extends to its military strategy, which has focused on key economic areas at the expense of less strategically important parts of the Cabo Delgado province. Potentially, this reinforces the insurgents’ narrative that the FRELIMO government seeks to enrich itself at the expense of the poor.

Fourth, there is need for coordination among and between the actors. As noted above, there was need for strong regional and national coordination mechanisms, clear communication and a unified approach among SADC member states and other regional actors in dealing with the situation in Mozambique.

Fifth, a multidimensional approach is key. There seemed to be a lot of emphasis on hard power (military interventions at the expense of other softer approaches). Certainly, addressing the Mozambique crisis would require a multidimensional approach that encompasses military, humanitarian and development efforts. A focus solely on military operations was not sufficient to stabilise the region. Diplomacy and negotiation efforts should have complemented military operations, and SADC should continuously engage with various stakeholders, including the Mozambican government and relevant non-state actors, local leaders, local community, to seek peaceful solutions. Other approaches such as community mediation and dialogue should have been encouraged. Given the human security implication of the insurgency/terrorism, it would have been necessary to draw lessons using human security approaches to diffuse these insecurities. Cabo Delgado’s history and developmental profile, anchored on political, social, poverty and economic dynamics, calls for the consideration of human security perspectives, without which peace and security would be difficult to achieve (Kaldor, 2011). Poverty and underdevelopment are at the heart of the province’s human insecurity. In this regard, taking a human security approach is essential as human security tenets are anchored on prevention of insecurity, identifying root causes of insecurity and putting an individual at the centre of analysis (Zwitter, 2010).

Lastly, there is a need to build African capacity to respond to security challenges without overreliance on foreign partners. While foreign support/intervention has been critical in supporting various interventions and in helping to improve security in parts of the Cabo Delgado province, concerns over sustainability continue to linger. The intervention in Somalia that solely depended on foreign financing provides a good example that overreliance on donors, especially in dealing with the malady of terrorism, is not sustainable. There is need for Africa to develop and strengthen its self-financing model. The AU Peace Fund is an example that could be drawn upon to deal with its perennial peace and security challenges.

5. Conclusion

Terrorism in Mozambique had deep roots, owing to various conflict dynamics such as marginalisation and poor socio-economic conditions across Cabo Delgado. In addition, the historical inequalities in the province added a layer of problems that needed a coordinated and inclusive approach. The military intervention of Rwanda (Penney, 2023) and SAMIM attempted to suppress the insurgency; however, serious structural issues persisted. While SAMIM intentions were clear from the onset in terms of establishing regional solutions to this complex situation of terrorism and violent extremism, there were still considerable gaps in logistics, operational capacity and policies. Therefore, a holistic approach is needed, which would include a human security stance when responding to complex crises such as violence in Mozambique’s Cabo Delgado province.

Lastly, SADC as a regional body needs to be proactive. It needs to strengthen its regional counter-terrorism centre to monitor and address the terrorism menace in the region. It is clear from the discussions that there is a need to move away from hard power in terms of responding to insurgency/terrorism. This means that inculcation and infusion of soft power could have been prioritised – provision of social amenities and basic needs, community mediation and dialogue to address the challenges. Lessons can also be drawn from countries such as Nigeria, Egypt and Somalia that have been dealing with the problem of terrorism for quite some time. This is critical for cross learning and strengthening local interventions to the problem. Strong coordination among the various actors on the ground is also critical for intervention to have greater impact.

Reference List

ACAPS. (2020) Mozambique: Deteriorating humanitarian situation in Cabo Delgado province [Internet]. Available from: <https://www.acaps.org/sites/acaps/files/products/files/20200408_acaps_short_note_cabo_delgado_mozambique_0.pdf> [Accessed on 3 March 2023].

Adelaja, A. and George, J. (2020) Is youth unemployment related to domestic terrorism? Perspectives on Terrorism, 14 (5), pp. 41‒62.

Africa Centre for the Study and Research on Terrorism (ACSRT). (27–29 September 2023). African Union Legal Instruments on the Prevention and Countering of Violent Extremism and Cross-border Cooperation [Unpublished Conference presentation]. Mobilizing Collective Intelligence to Counter and Prevent Violent Extremism and Terrorism in Africa: Maputo.

Alden, C. and Chichava, S. (2021) Cabo Delgado: ‘Al Shabaab/ISIS’ and the Crisis in Southern Africa. Policy Centre for the New South. Rabat.

Amnesty International. (2021) Mozambique: “What I saw is death”: War crimes in Mozambique’s forgotten cape [Internet]. Available from: <https://www.amnesty.org/en/documents/afr41/3545/2021/en/> [Accessed on 14 September 2023].

Anum, S.A. (2017) The New Insurgencies and Mass Uprisings in Africa and International Involvement: Selected Case Studies. University of Pretoria, South Africa.

Ballard, S. (2022) Enhancing humanitarian aid and security in Northern Mozambique. Centre for Strategic and International Studies [Internet]. Available from: <https://www.csis.org/analysis/enhancing-humanitarian-aid-and-security-northern-mozambique> [Accessed on 15 September 2023].

Bissada, A.M. (2020) Mozambique: Can Cabo Delgado’s Islamist insurgency be Stopped? The Africa Report [Internet], 29 July. Available from: <https://www.theafricareport.com/35435/mozambique-can-cabo-delgados-islamist-insurgency-be-stopped/> [Accessed on 3 June 2024].

Bolani, N. (2021) SADC to deploy regional standby force to Mozambique. SABC News [Internet], 23 June. Available from: <https://www. sabcnews.com/> [Accessed on 15 September 2023].

Bussotti, L. and Coimbra, E. (2023) Struggling the Islamic State in Austral Africa: The SADC military intervention in Cabo Delgado (Mozambique) and its limits. Frontiers in Political Science [Internet], 5 (1). doi: https://doi.org/10.3389/fpos.2023.1122373

Campbell, J. (2020) How Jihadi groups in Africa will exploit COVID-19. Council on Foreign Relations [Internet]. Available from: <https://www.cfr.org/blog/how-jihadi-groups-africa-will-exploit-covid-19> [Accessed on 15 February 2024].

Cascais, A. (2021) Rwanda’s anti-terror mission in Mozambique. Deutsche Welle (DW) [Internet]. Available from: <https://www.dw.com/en/rwandas-military-intervention-in-mozambique-raises-eyebrows/a-58957275> [Accessed on 16 September 2023].

Chingotuane, É.V.F., Sidumo, E.R.I., Hendricks, C. and van Nieuwkerk, A. (2021) Strategic options for managing violent extremism in southern Africa: The case of Mozambique. Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung, Maputo Office.

Columbo, E. (2023) The enduring counterterrorism challenge in Mozambique. CTC Sentinel, 16 (3), pp. 1‒6.

De Silva, S. (2017) Role of education in the prevention of violent extremism. Washington, D.C., World Bank Group.

DefenceWeb. (2022) SAMIM finance and logistics a concern for AU Peace and Security Council. [Internet]. Available from: <https://www.defenceweb.co.za/featured/samim-finance-and-logistics-a-concern-for-au-peace-and-security-council>[Accessed on 20 September 2023].

Deleglise, D. (2021) Issues and options for the SADC Standby Force mission in Mozambique. ACCORD [Internet]. Available from: <https://www.accord.org.za/analysis/issues-and-options-for-the-sadc-standby-force-mission-in-mozambique/> [Accessed on 15 September 2023].

Domson-Lindsay, A.K. (2022) Mozambique’s security challenges: Routinised response or broader approach? African Security Review, 31 (1), pp. 3‒18.

Dzinesa, G.A. (2023) The Southern African Development Community’s Mission in Mozambique (SAMIM): Policymaking and Effectiveness. International Peacekeeping, 30 (2), pp. 198‒229.

Engel, U. (2023) African Union Non-Military Conflict Interventions. In: The Palgrave Handbook of Diplomatic Thought and Practice in the Digital Age. Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp. 313‒331.

Ewi, M. and Aning, K. (2006) Assessing the role of the African Union in preventing and combating terrorism in Africa. African Security Review, 15 (3), pp. 32‒46.

Faria, P.C.J. (2021) The rise and root causes of Islamic insurgency in Mozambique and its security implication to the region. IPSS Policy Brief, 5 (4).

Klobucista, C., Masters, J., & Sergie, M. A. (2021). Backgrounder: al-Shabaab. Council on Foreign Relations, [Internet]. Available from: https://www.cfr.org/backgrounder/al-shabaab [Accessed on 20 September 2023].

Galula, D. (1964) Counterinsurgency Warfare: Theory and Practice. New York, Praeger.

Gberie, L. (2016) Terrorism overshadows internal conflicts. Africa Renewal, 30 (1), pp. 32‒35.

Gunaratna, R. (2008) Understanding the challenge of ideological extremism. Revista UNISCI, 18, pp. 113‒126.

Ibrahim, I.Y. (2017) The wave of Jihadist insurgency in West Africa: Global ideology, local context, individual motivations. West African Papers, No. 07. Paris, OECD Publishing.

International Crisis Group. (2021) Stemming the Insurrection in Mozambique’s Cabo Delgado. International Crisis Group [Internet]. Available from: <https://www.crisisgroup.org/africa/southern-africa/mozambique/303-stemming-insurrection-mozambiques-cabo-delgado> [Accessed on 20 September 2023].

Jones, S. (2008) The rise of Afghanistan’s insurgency: State failure and Jihad. International Security 32, p. 4.

Jones, S. (2009) In the Graveyard of Empires. New York, W.W. Norton & Company, Inc.

Kaldor, M. (2011) Human security in complex operations. Prism, 2 (2), pp. 3‒14.

Khadiagala, G.M. (2015) Silencing the guns: Strengthening governance to prevent, manage, and resolve conflicts in Africa. New York, International Peace Institute, 1‒32.

Langa, M. F. (2021). Terrorism as a challenge for promotion of human security in Africa: A case study of Mozambique’s Cabo Delgado province. Journal of Central and Eastern European African Studies, 1(3), 53-67.

Louw-Vaudran, L. (2022) SADC and Rwanda shouldn’t go it alone in Mozambique. Institute for Security Studies (ISS) [Internet]. Available from: <https://issafrica.org/iss-today/sadc-and-rwanda-shouldnt-go-it-alone-in-mozambique> [Accessed on 7 April 2024].

Makonye, F. (2022) Dissecting the Franco-Rwandese Alliance in Southern Africa: Case of Cabo Delgado, Mozambique. Journal of African Foreign Affairs, 9 (3), pp. 161‒172.

Mandigo, W., Wibisono, M. and Pramono, B. (2023) Southern African Development Community application of Collective Security Against Al Sunnah Terrorists in Mozambique (2015‒2021). International Journal of Humanities Education and Social Sciences, 2 (6), pp 1790-1797.

Matsinhe, D.M. and Valoi, E. (2019) The genesis of insurgency in northern Mozambique. Institute of Security Studies (ISS) Southern Africa Report, 2019 (27), pp. 1‒24.

Morier-Genoud, E. (2020) The Jihadi insurgency in Mozambique: Origins, nature and beginning. Journal of Eastern African Studies, 14 (3), pp. 396‒412.

Neethling, T. (2021) Natural gas production in Mozambique and the political risk of Islamic militancy. The Thinker, 89 (4), pp. 85‒94.

Nhamire, B. (2021) Will foreign intervention end terrorism in Cabo Delgado? Institute for Security Studies Policy Brief [Internet]. Available from: <https://africaportal.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/policy-brief-165.pdf> [Accessed on 7 April 2024].

Nunez-Chaim G. and Pape, U.J. (2022) Poverty and violence: The immediate impact of terrorist attacks against civilians in Somalia. World Bank Group Policy Research Working Papers. Volume 10169 [Internet]. Available from: <https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/099415109082281442/pdf/IDU03861d1b0002f304b090b8c80ea73003b5ba6.pdf> [Accessed on 7 April 2024].

Obaji Jr, P. (2021) Growing insurgency in Mozambique poses danger to Southern Africa. IPI Global Observatory [Internet]. Available from: <https://theglobalobservatory.org/2021/03/growing-insurgency-mozambique-poses-danger-southern-africa/> [Accessed on 7 April 2024].

Otiso, K. (2009). Kenya in the crosshairs of global terrorism: fighting terrorism at the periphery, Kenya Studies Review, 1(1), pp. 107–132.

Penney, J. (2023) Rwanda helped oust Jihadists in Mozambique. Can this model work in West Africa. Pass Blue [Internet]. Available from: <https://www.passblue.com/2023/08/16/rwanda-helped-oust-jihadists-in-mozambique-can-it-work-as-a-counterinsurgency-model-in-west-africa/> [Accessed on 5 April 2024].

Piehl, A.M. (1998) Economic conditions, work, and crime, In: Michael Tonry, ed. Handbook on Crime and Punishment. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 302‒19.

Ruhm, C. (2000) Are recessions good for your health? Quarterly Journal of Economics, 115 (2), pp. 617.

Sheehy, T. (2021) Five keys to tackling the crisis in Mozambique’s Cabo Delgado. United States Institute of Peace, p. 28.

Sidumo, E., Svicevic, M., and Bradley, M. M. (2024) Introduction: The evolving conflict in northern Mozambique and the rise of Ansar al-Sunna. In Mozambique’s Cabo Delgado Conflict (pp. 1–16). Routledge.

Sithole, T. (2022) The political economy of Mozambique’s Cabo Delgado insurgency and its impact on Southern Africa’s regional security. Politikon: The IAPSS Journal of Political Science, 52, pp. 4‒29.

Southern African Development Community (SADC) (2021). SADC Mission in Mozambique (SAMIM) in Brief. Southern African Development Community (SADC) [Internet]. Available from: <https://www.sadc.int/latest-news/sadc-mission-mozambique-samim-brief> [Accessed on 7 April 2024].

Steinberg, G., and Weber, A. (2015) Jihadism in Africa: local causes, regional expansion, international alliances [Internet]. Available from: https://nbn-resolving.org/urn:nbn:de:0168-ssoar-435405 [Accessed on 7 April 2024].

Ugwueze, M.I. and Onuoha, F.C. (2020) Hard versus soft measures to security: Explaining the failure of counter-terrorism strategy in Nigeria. Journal of Applied Security Research, 15 (4), pp. 547‒567.

United Nations (UN). (2015) Plan of Action to Prevent Violent Extremism: Report of the Secretary-General. United Nations [Internet]. Available from: <https://issat.dcaf.ch/ara/download/100959/1785072/Plan%20of%20Action%20to%20prevent%20Violent%20Extremism.pdf> [Accessed on 23 September 2023].

United Nations Development Programme (UNDP). (2020) Preventing violent extremism. UNDP [Internet]. Available from: <https://www.undp.org/content/undp/en/home/2030-agenda-for-sustainable-development/peace/conflict-prevention/preventing-violent-extremism.html> [Accessed on 17 April 2020].

United Nations Development Programme (UNDP). (2023) Dynamics of violent extremism in Africa: Conflict ecosystems, political ecology and the spread of the proto-state. Research Paper. New York.

United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (UNOCHA) (2020) Flash appeal for COVID-19 Mozambique. United Nations [Internet]. Available from: https://mozambique.un.org/sites/default/files/2020-08/MOZ_20200604_COVID-19_Flash_Appeal_0.pdf [Accessed on 22 January 2024].

United States Army. (2007) Counterinsurgency Field Manual No. 3‒24. Chicago, University of Chicago Press.United States Institute of Peace. (2002) Islam and Democracy. United States Institute of Peace [Internet]. Available from: <https://www.usip.org/sites/default/files/resources/sr93.pdf> [Accessed on 22 September 2021].

Van Nieuwkerk, A. (2013) SIPO II: Too little, too late? The Strategic Review for Southern Africa, 35 (1), pp. 146 – 153.

Vhumbunu, C.H. (2021) Insurgency in Mozambique: The role of the Southern African Development Community. Conflict Trends, 2021 (1), pp. 3‒12.

Wilkinson, P. (2001) Terrorism Versus Democracy: The Liberal State Response. London, Frank Cass.

Yussuf, M. (2023) Terrorists “try to persuade” the population of Kalugo, in Mocímboa da Praia. Integrity Magazine [Internet]. Available from: <https://integritymagazine.co.mz/arquivos/8476> [Accessed on: 20 September 2023].

Zamfir, I. (2021) Security situation in Mozambique. European Parliament [Internet]. Available from: <https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/ATAG/2021/689376/EPRS_ATA(2021)689376_EN.pdf> [Accessed on 15 February 2024].

Zwitter, A. (2010) Human Security, Law and the Prevention of Terrorism. London. Routledge.