Abstract

Farmer-herder conflict is an age-old phenomenon, which is widely spread in the West African sub-region. Current studies on the Ghanaian farmer-herder conflict have emphasised the land-related conflicts between indigenous farmers and nomadic herders. It has focused especially on environmental scarcity and climate change approaches. However, this study adopts the political ecology framework to highlight land conflicts between migrant farmers and nomadic herders, two migrant groups that are considered “strangers” to the Kwahu Afram Plains District. The study contributes to the broader debates on farmer-herder conflict. It provides contrary evidence with regard to the popular notion in literature and theory about the prevalence of land insecurity among nomadic herders. The study argues that migrant farmers in the study area experience more land insecurity compared to the nomadic herders. This is because of their history of immigration, their relationship with the Kwahu landowners, which is driving the escalating cost of accessing land, and disputes between landowning groups.

Introduction

Farmer-herder conflict is a long-standing phenomenon. From a Christian-centred analytical lens, the biblical story of Cain and Abel’s conflict, which resulted in the former killing the latter, is a prototypical example of farmer-herder conflict (Benjaminsen et al., 2009). The biblical illustration depicts the past co-existence of farmers and herders, despite some level of animosity between them. According to Seddon and Sumberg (1997), past relationships between farmers and herders were mutually beneficial and complementary. Such interactions were crucial in preventing and resolving conflicts between farmers and herders. The current widespread and intense conflicts in Africa between farmers and herders suggest that the symbiotic relationships between the two groups are becoming less important. As a consequence, it has become more difficult to regulate conflict between the two feuding parties.

These conflicts in Ghana are characterised by retaliatory attacks. According to Otu and Impraim (2021) citing the 2018 report of the West African Network for Peacebuilding (WANEP), there are widespread incidents of armed attacks. These attacks are launched by herders at Zabzugu, Boliga Nkwanta, Agogo, Drobonso, Geduako, Nsuta, Abokpa, Afram Plains, and Ntrongnan. Similar violent farmer-herder conflicts have been documented in Dumso, Nangodi, Gushegu, Atebubu/ Amanten, and Pru (Olaniyan et al., 2015). The outcomes of these conflicts have resulted in the loss of lives, injuries, and property.

The reason for these conflicts on the African continent is a subject of extensive academic debate. These debates are highly contested, with perspectives and arguments on the phenomenon differing in their intricacies (Otu, 2022). Cultural diversity, power dynamics, and changes in livelihood have all contributed to conflict between farmers and herders. However, the present study focuses on conflict arising between the two groups over land access challenges. Past studies on farmer-herder conflicts have typically concentrated on conflicts between indigenous farmers and migrant herders (see Tonah, 2005; Moritz, 2006; Mbih, 2020; Paalo, 2021; Issifu et al., 2022). Such studies have focused on the stronger claims of indigeneity by indigenous farmers.

This is opposed to the weaker claims of migrants to land and the spatiotemporal nature of the land rights of the herders (Kugbega and Aboagye, 2021).

These studies also draw on the modernisation discourse of the environment and the perception that the activities of the nomadic herders are destructive to the environment. Therefore, they do not enjoy the support of policymakers and policy processes leading to their marginalisation and limited access to land (Benjaminsen et al., 2009). Moreover, the assumption was that land insecurity was more common among nomadic herders. However, this case study shows that land insecurity is more prevalent among settler farmers. Also, in the struggle for access to land between settler farmers and the nomadic herders in the Kwahu Afram Plains South District, the situation of the settler farmers is more precarious and dire. Acquiring the often-overlooked perspective of migrant groups has changed the lens. It draws attention to migrant groups as victims of the financial calculations of landowning groups, fundamentally changing both popular and academic narratives of the so-called Fulani menace (Kuusaana and Bukari, 2015; Tonah, 2005).

The rest of the article is organised as follows. Section 2 discusses the usefulness of the political ecology approach in interrogating farmer-herder conflicts. This is followed by an overview of farmer-herder conflicts in the Kwahu Afram Plains South District. Section 3 introduces the study area and the methodology used to conduct the study, while Sections 4 and 5 present the results and discussion. The conclusion in Section 6 reinforces the relevance of the political ecology theory. It highlights the plight of settler farmers who are victims of the financial calculations of landowning groups due to their weaker claim to customary land. As a result, some recommendations are made with regard to peacebuilding in the West African sub-region. These recommendations focus more specifically on a peaceful coexistence between farmers and nomadic herders in Ghana.

Understanding farmer-herder conflict through the political ecology lens

The study of the farmer-herder conflict across Africa has taken a variety of approaches, ranging from the impact of environmental scarcity (Homer-Dixon, 1999; Homer-Dixon and Percival, 1995) to climate change (Froese and Schilling, 2019; Dosu, 2011; Reuveny, 2007). Environmental scarcity and climate change are useful in explicating how increasing numbers in population, large-scale land acquisition, and climate variability are affecting the availability of land. This leads to increased contestation and competition for land that engenders conflicts. However, these approaches ignore the power dynamics among the actors involved. This is where political ecology is needed (Robbins, 2012; Benjaminsen et al., 2009; Watts, 2000).

Political ecology which emanated from the field of geography has become a principal approach in many fields of study in recent years. There are five overriding narratives or foci of political ecology which include, degradation and marginalisation; conservation and control; environmental conflict and exclusion; the environmental subjects and identity; and political objects and actor thesis (Robbins, 2019). However, the fundamental element that unites all these narratives is the interplay of power. As espoused by Robbins (2004:12), in his definition, cited by Benjaminsen & Svarstad (2021), political ecology is “empirical, research-based explorations to explain linkages in the condition and change of social/environmental systems, with explicit consideration of relations of power” (Benjaminsen & Svarstad, 2021:15). Watts (2000) also argues that political ecology necessitates a careful examination of the different ways that resources are accessed and controlled, as well as what their effects are on sustainable livelihood. The centrality of powers in political ecology is not limited to only one level of analysis. Instead, the power relations among different actors within the local setting are linked to political and economic influences emanating from national and international levels (Benjaminsen & Svarstad, 2021; Robbins, 2019). This idea is succinctly articulated in a comment that “any tug on the strands of the global web of humans-environment linkages reverberates throughout the system as a whole” (Robbins, 2019:10). The power dynamics are critical to this study. It provides useful information about the composition of the case study communities and how not to perceive the actors within such communities as a homogeneous group. Rather they should be viewed as heterogeneous power-wielding groups with different levels of bargaining power and different ways of interacting with the landowners. This generates different reactions that sometimes leads

to conflict.

Three different processes are often pursued in political ecology. First is the process that involves how international capital investment affects livelihood through its impact on the environment and access to land as seen in mining, agricultural production and manufacturing ventures (Benjaminsen & Svarstad, 2021). Second, it also studies how international conservationist institutions rely on national governments to alter the local use of land and natural resources in an attempt to solve global environmental and climate problems. This takes place through the establishment of “new national parks, or climate mitigation projects such as the production of biofuel or to sequester carbon to conserve forests or establish new forest plantations” (Benjaminsen & Svarstad, 2021:5). Finally, political ecology also focuses on environmental change by addressing the processes of change, its causes, and impacts (Benjaminsen & Svarstad, 2021). Even though all three issues raised are useful analytical frameworks, for this study our focus is on the power dynamics with regard to access to land and natural resources. This study draws on political ecology in the discussion of the conflict between settler farmers and nomadic herders. It argues that to improve the appreciation of farmer-herder conflicts in the Kwahu Afram Plains South District, a thorough understanding is needed of: (1) the historical context; (2) the role of political elites; and (3) the politics of land ownership between traditional authorities that empower one group over and above the other.

Drawing on the foregoing, the use of political ecology theory to assess farmer-herder conflict is based on an important premise. The premise suggests that the reciprocal and monetary gains between societal “big men” (traditional authorities and landowners) grant nomadic herders land access, harming settler farmers. It is a situation which is contrary to several studies that always found the herders to be in a disadvantaged position (Benjaminsen and Ba, 2019; Kuusaana and Bukari, 2015). The herders are granted land at the expense of the settler farming communities. This results in competition for land between the two migrant groups, which inevitably leads to violent conflict in the research study area.

Farmer-herder conflict in the Kwahu Afram Plains South District: An overview

Conflicts between farmers and herders have been recorded in many areas in Ghana. In 1988/89 and 1999/2000, the repeated clashes between the Fulani pastoralists and farmers resulted in the expulsion of the former (Olaniyan et al., 2015; Tonah, 2002). More recently, the farmer-herder conflicts in the Agogo area which is conterminous to the Kwahu Afram Plains have not escaped scrutiny from academics (Setrana, 2021). In the Afram Plains, the conflict between farmers and herders has been very rife. Both local and national media published articles reporting clashes between the two migrant groups, portraying it as gruesome, violent, and on the rise (Otu and Impraim, 2021). These media reportages further enhance the narratives about the effects of the conflict on the people’s livelihood in the area. Otu and Impraim (2021) documented cases of farm destruction by the cattle of nomadic herders and farmers retaliating in the Kwahu Afram Plains South District. In one instance, in October 2020, crop farmers mobilised and attacked nomadic herders in the Aframso community, essentially to evict the herders from the land. The resultant outcome of the deadly clash led to the death of nine nomadic Fulani herders and two Konkomba settler farmers, including two brothers. Another development portrayed how in a farming village in Gyeneboafo in the case study area, a Fulani herder shot a settler farmer in the abdomen. This occurred when the farmer questioned the Fulani herder on why his cattle were eating crops that the farmer is yet to harvest on his farm. Both actions by the two parties directly impacted the livelihood of the people and exacerbated the level of insecurity.

The Kwahu Afram Plain has been in the hands of the Kwahu people since the Gold Coast border demarcation in 1902 (Wallis, 1953). Historically, the Kwahu Afram Plains South District (KAPSD) was sparsely populated with a few settlements and was used as a hunting ground by the Kwahu landowners (Tonah, 2005). The Kwahu landowners lived in the major towns in the plains and only a few of them resided in the villages as the representatives of the landowning group. They mainly engage in trading and formal work in the communities and only a minority engage in farming activities around the main settlements. The area has witnessed an influx of migrants from all parts of Ghana and the neighbouring West African countries since the 1960s (Tonah, 2005). Apart from the favourable ecological environment, the presence of these two migrant groups in the area can be attributed to three things. These three things are construction of the Akosombo dam, the decentralisation of Ghana’s political space, and the introduction of cocoa cultivation (Tonah, 2005). These migrants engaged in different activities including commercial and subsistence farming, hunting, fishing, herding, trading, and other related activities. Of all the livelihood activities, farming and herding have generated intense competition for land, leading to inevitable resource conflicts.

The farmers and the fishermen were the first of the migrant groups to have arrived in the area. They requested land from the traditional Kwahu landowners to engage in subsistence agricultural activities. These migrants were predominantly the Ewe and Dangme from Volta and the Greater Accra Regions respectively and the Konkomba, Gonja and Dagaaba from the northern part of the country. The Ewe and Dangme groups settled along the banks of the Afram and Volta rivers to ply their trade of fishing. This is why the Konkombas and the others from the northern sector preferred the hinterland. Here they could access enough land to engage in food crop cultivation under the system of shifting cultivation and bush fallowing (Sarfo, 2011). In recent times, there has been increased interest from multinational corporations engaging in large-scale land acquisition and commercial farmers from the major cities in Ghana for various forms of investment. Parallel to the migration of the above groups is the influx of nomadic Fulani herders looking for the same land in order to graze their cattle. Interestingly, these nomads previously avoided the area due to its dense nature and the presence of tsetse flies. The nomads have moved into the area because of the dwindling ecological resources in the Sahel and its extension to the northern regions of Ghana (Tonah, 2002).

The interactions of these two migrant groups within the same ecological space have resulted in a struggle for land and natural resources in pursuit of their respective livelihood activities. While the settler farmers need more land to expand their crop farms, nomadic herders require the same amount of land to graze their cattle. The settler farmers believe that because they have cultivated the land for a longer period, their use rights to the land must be respected. The nomads, on the other hand, argued for having a legitimate agreement to use the land with the traditional authorities, which must be respected by the farmers. Both migrant groups claim legitimate use rights of land in the research study area.

The jostling for land between the two migrant groups has opened up an opportunity for some traditional leaders to exploit the situation. The actions taken by the landowners have resulted in the majority of settler farmers becoming landless and, in some cases, losing their crops to the herders. This situation has arisen because most of the lands that the farmers once cultivated have now been allocated to the nomadic herders, without their knowledge or consent. This brings the herds closer to the crop fields of farmers, leading to the destruction of farms and other retaliatory consequences (Yambilah and Grant, 2014; Tonah, 2006). As a result, both migrant groups are now at odds with one another because they perceive each other as an obstacle to obtaining their means of sustenance. Since then, farmer-herder conflicts have been a recurring problem in the case study area.

Materials and Methods

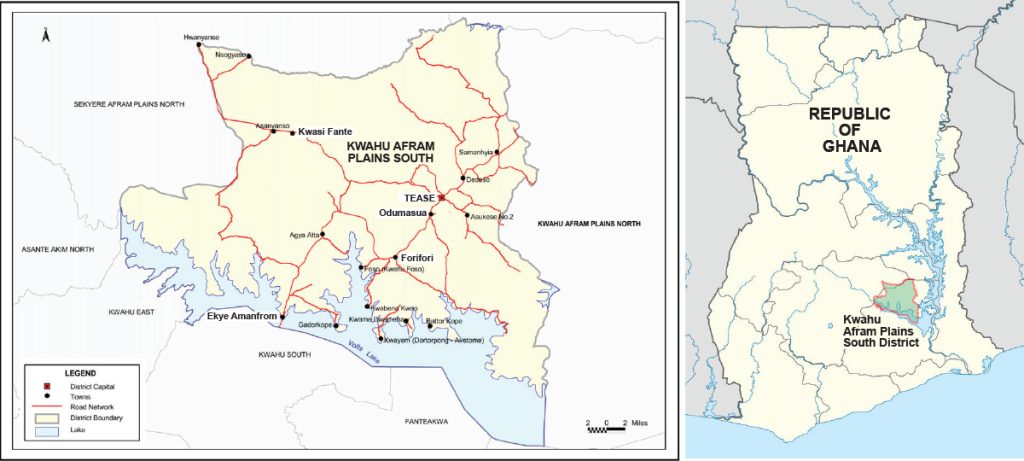

The study was done in the Kwahu Afram Plains South District. The district was created in 2012 by Legislative Instrument (LI) 2045 (GSS, 2014). Even though farmer-herder conflict occurs in many parts of the country, the Kwahu Afram Plains South District presents an unusual situation. This is because the majority of the residents are primarily non-indigenous people with weaker claims to customary lands in the area. This is contrary to farmer-herder conflicts between indigenes and migrant herders in other parts of the country with the former asserting their claim to land. Additionally, as part of the cattle migratory corridor of Ghana (Tonah, 2005), the Afram Plains area serves an important purpose. It is the final destination of the nomadic herders from the Sahelian region of West Africa during the seasonal migration. This has caused the area to experience a heavy presence of cattle from both the Fulani nomadic herders and locally based herders, particularly during the dry season. The expansion of farm sizes and the heavy presence of cattle brought by the nomadic herders amidst insecure land tenure have created tensions. These tensions usually escalate into conflicts between farmers and herders in the Afram Plains. Farmer-herder conflict in the area has gained notorious status to the extent that the farmer-herder conflict in Ghana has become synonymous with Afram Plains. The area has also been identified as part of the bread basket of Ghana (Yeboah, Codjoe and Maingi, 2013). Therefore, the Kwahu Afram Plains South District serves as an ideal place to interrogate the political ecology of farmer-herder conflicts in Ghana. Data for the study had been collected in 2019. However, further field visits were made in 2021 to validate and confirm the findings. In the case study district, fieldwork was conducted in the communities of Kwasi Fante, Ekye Amanfrom, Odumasua, Tease and Forifori. These are well-known areas in the study district where residents resist the presence of nomadic herders and their cattle.

Figure 1: Research study areas in the Kwahu Afram Plains South District (KAPSD).

To obtain qualitative data for the study, semi-structured interviews and focus group discussions (FGDs) were used. Focus group discussions and interviews were conducted primarily with settler farmers who live in nucleated settlements and are easier to mobilise. For nomadic herders who were dispersed in their camps, semi-structured interviews were used. Additional information was obtained through interviews with stakeholders in the area, including traditional/opinion leaders and local government officials. A total of 29 participants participated in the study: fourteen settler farmers, seven nomadic herders, four traditional/opinion leaders, and four government officials. The information gathered, primarily in the Ghanaian language (Twi) and Hausa, was transcribed into English. This was made possible through the use of NVivo, a qualitative software that helped to generate the dominant themes and patterns in the research. The descriptive information and the direct quotes used in the research were derived from the transcript analysis.

Results

Land Relations in the Kwahu Afram Plains South District

In Ghana, there is a plurality of land tenure and land administration. Land has been classified into three categories, state lands, vested land and customary land (Amanor, 2009; Kasanga and Kotei, 2001). Land in the study area belongs to the customary sector where the customary norms of the particular community mediate land tenure relations. The customary tenure recognises several rights over land including the allodial or ultimate title vested in the traditional leaders and family heads to manage land on behalf of their subjects. There is also the usufructuary right that enjoins the indigenes of the area unhindered access to land once such land is not in use or claimed by another. Tenancy grants individuals access rights to use the land in exchange for payment through tributes or royalties in cash or in kind. Access rights could also be obtained through leases and licences. In the Kwahu Afram Plains South District, the allodial title is vested in the Kwahu landowners.

This is where the two migrant groups have for several years been obtaining access to land through tenancies when tributes or royalties have been marginal.

The population explosion and increasing infiltration of nomadic herders in the area have contributed to complex consequences. As a result, in the research study area, the relations over the land between traditional landowners and migrants have evolved over the years. Interviews revealed that land access has changed from the traditional egalitarian mode to more market-determined pathways. This has led to strained relations between the Kwahu landowners and the settler farmers. An opinion leader explained that:

It is necessary to understand that there was already an uneasy calm between traditional authorities who are custodians of the customary lands in the area and the settler farmers, particularly the Ewe settler farmers, before the arrival of nomadic herders in the area (Interview, opinion leader, November 2019).

Further interviews with key stakeholders revealed that the long-standing conflict between landowners and migrant settlers stems from who controls the resettlement lands in the area. The Kwahu landowners claim ownership of the resettlement lands. By contrast, Ewe migrants also have a claim. They were displaced because of the construction of the Akosombo dam and resettled in the area. Therefore, they claim that they or the government have control over such resettlement areas. The age-old tension between the two parties explains why the Kwahu landowners prefer to give nomadic herders priority access to land in the area. More so, the money derived from giving land access rights to nomadic herders and commercial farmers far exceeds that of the settler peasant farmers.

A 56-year-old settler farmer in an interview lamented:

The landowners want to displace us from the land which is why they give the same piece of land we are cultivating to the herdsmen. They say the money we pay for accessing land is too small but the Fulani people can give much money. Sometimes when we complain about the destruction of our crops, the landowners will tell us to leave the place if we are uncomfortable with the presence of the Fulani herders (Interview, settler farmer, November 2019).

This view was shared by several settler farmers and partly accounts for the escalating cost of accessing land by the settler farmers. A settler farmer expressed his opinion on the arbitrary nature of land rent as follows, “I rented an acre of land last year for 20 Ghana Cedis. This year, the landowner wants me to pay 250 Ghana Cedis (1$=12Ghana cedis) for the same piece of land. How can I afford this considering that I am a smallholder who grows food crops for the consumption of my family? There is a threat to our livelihood” (Interview, settler farmer, November 2019). This view is not different from the interviews and discussions with other settler farmers in the district.

Discussants during FGDs strongly expressed the following sentiments:

Some traditional authorities show favour in land allocation and access to nomadic herders because of money and, in some cases, cattle that have exchanged hands between them, as well as the landowners’ subtle attempt to evict us from the land. Some chiefs’ reluctance to rent farming land during a specific time of the year, particularly during the dry season, in anticipation of higher rent from nomadic herders, is one example of unfair land practices in the area. Furthermore, some chiefs purposefully assign grazing lands nearer to places where settler farmers cultivate, thereby, bringing cattle closer and creating the condition for conflict between farmers and herders (FGDs, settler farmers, December 2019).

A herder who was incensed commented as follows:

The farmers say we are herding close to their crop fields. Did we rent the land from them? If they have any concerns, they should direct them to the landowners and leave us alone. Our cattle will graze in the area that has been demarcated to us by the chiefs (Interview, nomadic herder, November 2019).

The tension relative to the conflict of allocating land to nomadic herders hinges on the fact that the two groups are competing for land in pursuit of their livelihood. The farmers have cultivated the land for many years. This is while the new arrivals, the nomadic herders, have courted the support of traditional landowners. They used the support of traditional landowners to allocate land to them that is already under cultivation by farmers or closer to crop fields. This has ultimately led to crop destruction by the herders’ cattle. These contested areas are fertile lands and mostly closer to the river banks. Therefore, the landowners, by the power vested in them to allocate land, expropriated the land to the highest bidder. This emboldened the nomadic herders in their confrontation with the migrant farmers. The aforementioned situation has strained relations between farmers and herders. The settler farmers’ inability to challenge landowners has led them to undermine nomadic herders’ land use rights. According to a nomadic herder, “Farmers see us as a soft target in their conflict with landowners, which is why they attack us at the slightest provocation” (Interview, nomadic herder, November 2019).

The traditional landowners in the area are therefore using their fiduciary position to drive the escalating cost of accessing land. Thereby placing the smallholder settler farmers in a disadvantageous position in terms of access to land. This leads to tenure insecurity among the farmers as opposed to the nomads with the financial power. The resultant effect of this occurrence is an imbalance in the power to access land and natural resources leading to conflict between the two migrant groups in the area.

Access to Political and Business Elites

The research found that nomadic herders have access to the political and business elites, putting them in a position to access resources, particularly land. The study revealed that most nomads, in addition to caring for their cattle, also care for the cattle of some influential members while in the country. These political and business elites have made investments that have allowed them to own sizable cattle herds in a short time, thereby, making money off the presence of the nomadic herders. As a result, the political and business elites play an important role in the escalating tensions between the two migrant groups in the research study area. A settler farmer summarised the support of the political and business elites as follows:

The presence of nomadic herders benefits the political elites enormously. The majority of the cattle in this area are for the big men who live in the city. You cannot tell the difference between a foreigner’s cattle and an indigenous person’s cattle. The nomads on the outskirts of these communities are tendering the cattle of these powerful members of society (Interview, settler farmers, November 2019).

A 68-year-old settler farmer avers that the association of the herders with the political and business elites has emboldened them to engage in activities that the law frowns upon. He argued strongly that:

The support of the political and business elites has impelled the nomadic herders to engage in activities that violate national laws and, more specifically the district by-laws on the movement of livestock. The marauding herds destroy crop fields and contaminate water bodies with no remorse because they know they have the support of the ‘big men’ (Interview, settler farmer, December 2019).

Further interviews with some key stakeholders illustrated the impunity with which the herders operate in the case study district. Some engage in vices such as rape and shooting of farmers who confront them on their farms. This is while others brandish guns openly while herding their cattle either on the highways or through the bushes. This is a blatant violation of national laws on the carrying of guns and specifically of the district by-laws on the movement of livestock. These by-laws require all cattle to be sent to the ranch in the district. The herders by virtue of their closeness with the political and business elites are often under the illusion that they possess power and hence commit such infractions with impunity. The herders are aware that their political and business associates will use their influence to sabotage state institutions involved in managing the conflict, protecting them when violations occur.

What is significant relative to the association of the nomads with the political elites is the easy access to land. One striking narrative was the fact that while the settler farmers struggle to gain access to land, the nomads easily gain access. To a larger extent, they can even access land that is still under cultivation by the settler farmers. The resultant effect of this situation has been the struggle between settler farmers and nomadic herders to access land, especially areas closer to water bodies. The role of the political elites is, therefore, integral to the conflict process. This is because their interest in the community is more paramount than the general welfare of the community members. With the support of the political elites, the nomads incur the anger of the settler farmers. This creates enmity and tensions that easily culminate into reprisal aggression between the feuding parties, leading to mutual hostility and reverse-violent attacks at the least provocation.

In furtherance of the above, because of the support that the nomadic herders receive from the political elite and law enforcement agencies, there are complaints from the farmers. The complaints from the settler farmers about the destruction of their crops are not dealt with promptly. A settler farmer, in an interview, noted that the “go and come” attitude of the law enforcement agencies makes it unattractive to send their complaints about crop destruction to the police. Again, the burden of proof related to crop destruction lies with the farmer. The farmers not only have to prove that the crops have been destroyed but they also have to identify the herd that did the destruction. The task of identifying the herd is enormous as the destruction is done at night when the farmer might be asleep (Sarfo, 2011; Tonah, 2002). An opinion leader avers that wherever they go, the herdsmen have agents who are well-connected to the state institutions and political parties. Anytime that there is a dispute between the settler farmers and the nomadic herders, these agents, through their influence, would help the Fulani herders to circumvent the due process (Interview, opinion leader, December 2019). A farmer retorted angrily about the agents of the herders as follows, “The Fulani herders do not annoy me as their agents.” The common opinion about the agents was that they deprive farmers of their due compensation in the case of crop destruction, even when the nomadic herders have agreed to pay. In situations where the settler farmers feel that they are treated unfairly by law enforcement agencies during confrontations with the herders, they resort to violence. The Fulani herders retaliate in most instances.

Conflict over Rights to Landownership

Landownership rights are essential for gaining access to land. Indigenes, unlike migrant farmers, can assert their claim to the land in order to improve their livelihood. However, where migrants’ access to land is based on the discretion of the traditional landowners, a problem arises. In these cases, smallholders, especially migrant farmers with weaker land claims, are deprived of their already cultivated land and left landless. The study found that migrants gain access to land in the area through the traditional authorities, who control approximately 70% of the land in the area. Due to the migrants’ reliance on chiefs for land, any dispute between chiefs over claims to the same piece of land engenders tension. It negatively impacts the livelihood of the migrants, especially the settler farmers. The presence of several chiefs laying claim to, for example, Forifori, a resettlement community, poses a serious challenge. All the traditional leaders who have staked claims in the area have explicitly instructed migrants to seek their permission before cultivating the land. As a result, different chiefs have given the same plot of land to multiple users who are settler farmers and nomadic cattle herders. An opinion leader vividly described a violent incident that occurred when two different chiefs, disputing a piece of land, allocated it to different users as follows:

Not long ago our village was plunged into a state of mourning when two young newly married couples were shot at and killed instantly when some herders confronted them on why they were spraying weedicide on land they claimed had been rented to them. The said piece of land has been cultivated by the couples for about two years when they rented it from a chief in the next village. The same piece of land has also been allocated to the herders by a different chief in the area. The confrontation between the farmers and the herders led to an altercation which resulted in one of the herders shooting and killing the two farmers. The unfortunate incident occurred because the same piece of land was allocated to different users by two disputing chiefs laying claim to that piece of land (Interview, opinion leader, December 2019).

In a related development, a settler farmer described his experience of how the claims by different chiefs to the same piece of land affected him as follows:

I can’t understand why some of the landowners are inconsiderate. Last year, I was on the verge of losing my two-acre yam farm. Without a friend’s advice to pay rent to both chiefs laying claim to the land, the unthinkable could have occurred, and my family could have struggled to survive during the lean season. How long can I continue to pay rent to these disputing chiefs on the same piece of land as a smallholder farmer who cultivates mainly for home consumption (Interview, settler farmer, November 2019).

Observations and discussions reveal strikingly similar experiences in which farmers were required to pay land rent to different chiefs for a piece of land in the area. The settler farmers argue that refusing to pay to all the chiefs laying claim to the land means losing the land, thereby, adversely affecting their livelihoods. Again, landowners in the study area are noted for allocating land in the hinterlands occupied by migrant farmers to herders. This is especially the case when these lands are subject to contestation from other chiefs which exacerbates the already volatile relations between the farmers and nomadic herders.

The nomadic herders on their part confirmed the occurrence of different chiefs renting the same piece of land to different users. The herders, however, allege that the farmers are envious of them and always stake claim to the land where their cattle graze. A herder intimated that:

When we first rented and moved to graze our cattle here, there were no farms on the land. We have been grazing our cattle in peace until three months ago when a middle aged man came to inform us that the area has been rented to him and so we should move our cattle. Upon inquiring about the chief, he rented the land from and when the land was rented, we realised that it was not the same chief who rented out the land to us. We, however, insisted that we will not move anywhere and that the farmer should go and collect his money from the said chief. Although the farmer was not happy to hear that from us, he promised to come back with some community members to evict us from the land. We are fully prepared and ready for them. They should come and evict us from the land if they are men (Interview, nomadic herders, December 2019).

When multiple users are granted the same piece of land by different chiefs, the stage is set for conflict to erupt. Therefore, the conflict between settler farmers and nomadic herders is exacerbated by the dispute over which chief owns what land in the area.

Discussion

As observed earlier, political ecology deals with human-nature interaction and how these interactions are mediated through power dynamics. Access to natural resources including land is influenced by the individual’s position vis-a-vis others in his or her claim over such resources. Several studies have applied political ecology to analyse the farmer-herder conflicts between the indigenous farmers and the nomadic herders. It causes these conflicts to become a conflict between the autochthonous and immigrants who are often described as foreigners, leading to the conclusion that the pastoralists are often marginalised (Benjaminsen et al., 2009; Mbih, 2020). In this study, the theory has been applied to farmer-herder conflicts, particularly when both disputants are migrants with no land ownership rights in the area. Analysis of the findings suggests that the nature of landownership in the area causes a great deal of conflict. Because the traditional authorities control the majority of land in the area, migrants’ access to land is at the behest of the chiefs.

It is no secret that the chiefs prefer allocating land to nomadic herders instead of to settler farmers in the area. This study also revealed that comparatively, the nomadic herders are more financially endowed and politically connected than the migrant farmers and can access favour far and above the migrant farmers. However, these two groups are in constant competition because of the nature of their activities. Whereas the farmers are interested in the land in the hinterland for their activities, the nomadic herders are also looking for a vast territory to graze their cattle. This results in confrontation. The situation engenders animosity between migrant farmers and nomadic herders, resulting in tensions and, the eventual outbreak of conflict.

The findings are consistent with previous research, in which Tonah (2002) stated unequivocally that the chiefs prefer nomadic herders. Tonah claims that their presence has provided the traditional authorities, who control customary lands, with opportunities for prosperity. The largely customary land controlled by traditional authorities across Africa has made migrants vulnerable, as they are exploited through labour and cash prestation. This lends credence to the assertion that migrant farmers cultivating customary land are the most vulnerable to exploitation and eviction (Kuusaana, 2016). The literature demonstrates the vulnerability of migrants who lack land ownership rights. The stringent requirement for access to land, shorter lease terms, and arbitrary land rental fees all point to this vulnerability (Alhassan and Manuh, 2005). In some areas, attempts by traditional authorities to renegotiate terms on land access have occurred, leaving migrant farmers exploited in terms of the land they have farmed for many years (Chauveau and Colin, 2010; Ubink and Quan, 2008). This study has argued that the migrants, in general, are marginalised and exploited with regard to access to land and natural resources. However, the nomadic herders have an advantageous position over settler farmers in the study area. In the case study area, the nature of landownership has led to some traditional authorities taking the land from smallholder settler farmers. They then transferred the right to land to the “highest bidder” who are primarily nomadic cattle herders and large-scale agricultural investors. These opportunistic tendencies of some traditional leaders who control customary land create a perilous situation.

It causes smallholder settler farmers to lose access to farmland, resulting in

land-use conflict.

Conclusion and the way forward

For a large portion of the African population, access to land is essential for survival. This is because many people rely on it for a living. Therefore, any obstacle that prevents access to land threatens and deprives them of their livelihood. The struggle for access to land increases the value of land and opens a door for opportunistic actors to profit from. Because of this situation, the majority of migrant settlers are deprived of their farmlands. They find it even harder to gain access to new land for cultivation, which leads to conflict between settler farmers and nomadic herders. The occurrence of this particular type of land conflict has provided valuable insight. It shed light on the fact that land conflict can occur not only between indigenous and migrant groups but also between migrant groups. They both lack indigenous land rights and have weaker land claims as migrants, making them vulnerable and more prone to conflict. Farmer-herder conflict should not always be perceived from the indigenous-migrants standpoint. This is because there are different permutations involved and each situation should be analysed based on the prevailing power dynamics.

The study recommends the establishment of the Customary Land Secretariat (CLS) to streamline land management practices. The purpose is to improve proper records keeping, accurate and transparent management structures, and effective conflict resolution procedures such as Alternative Dispute Resolution (ADR). In line with the new Land Act (Act 1036 of 2020), the CLS will give meaning to the establishment of grants based on oral agreements. It will safeguard the tenure security of smallholders whose land access is predominately based on oral agreements. It will also minimise multiple allocations of land to competing groups. The establishment of this specialised agency should be done with the technical assistance of: (1) the Lands Commission; (2) the Office of the Administrator of Stool Lands and; (3) the Land Use and Spatial Authority. These measures, among others, will ensure the complete zoning for exclusive herding and farming activities leading to coexistence and relative peace between settler farmers and nomadic cattle herders.

There is also the need to facilitate communicative engagement with the feuding parties. In order to end the mistrust between farmers and herders, a favourable safe space for communication must be created. In such a space, the feuding parties will be able to talk openly and freely about the many bases of their claims in the conflict. This approach will further allow each party to see and think about the situation from the other party’s viewpoint. It will thereby establish a readiness to seek common ground collectively to enhance social cohesion. Open and honest communication can produce desirable peace outcomes for co-existence rather than the use of force by security agencies to curtail the conflict.

References

Alhassan, O and Manuh, T. (2005) Land registration in Eastern and Western Regions, Ghana. Securing land rights in Africa, Research Report No.5, International Institute for Environment and Development (IIED): London.

Amanor, K. (2009) Securing Land Rights in Ghana. In: Ubink, J. M. eds. Legalising land Rights- Local Practices, State Responses and Tenure Security in Africa, Asia and Latin America. Leiden, Leiden University Press.

Benjaminsen, T, Maganga, F and Abdallah, J.M. (2009) The Kilosa killings: political ecology of a farmer-herder conflict in Tanzania. Development and Change, 40 (3), pp. 423–445.

Benjaminsen, T and Boubacar, B. (2019) Why do pastoralists in Mali join jihadist groups? A political explanation. The Journal of Peasant Studies, 46(1), pp.1–20.

Benjaminsen, T and Svarstad, H. (2021) Political Ecology: A Critical Engagement with Global Environmental Issues. Cham: Palgrave MacMillan.

Chauveau, JP and Colin, JP. (2010). Customary transfers and land sales in Côte d’Ivoire: revisiting the embedded issues. Africa. 80 (1), pp. 81–103.

Dosu, A. (2011) Fulani-farmer conflict and climate change in Ghana: migrant Fulani herdsmen clashing with Ghanaian farmers in struggle for diminishing land and water resources. (ICE Case Studies No. 258). Washington DC: Inventory of Environmental Conflict (ICE).

Froese, R and Schilling, J. (2019) The nexus of climate change, land use and conflict. Current Climate Change Reports. 5, pp. 24–35.

Ghana Statistical Service. (2014) 2010 population and housing census. District Analytical Report: Kwahu Afram Plains South. GSS: Accra.

Homer-Dixon, T. (1999) Environment, scarcity, and violence. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press.

Homer-Dixon, T and Val, P. (1995) Environmental scarcity and violent conflict: the case of South Africa. In Project on environment, population, and security (EPS). Toronto: University of Toronto; Washington: American Association for the Advancement of Science.

Issifu, A.K, Darko, F.D and Paalo, S.A. (2022) Climate change, migration and farmer-herder conflict in Ghana. Conflict Resolution Quarterly, 39, pp. 421–439.

Kasanga, K and Kotey N.A. (2001) Land Management in Ghana: Building on Tradition and Modernity. London: International Institute for Environment and Development.

Kugbega, S.K and Aboagye, P.Y. (2002) Farmer-herder conflicts, tenure insecurity and farmer’s investment decisions in Agogo, Ghana. Agricultural and Food Economics, 9 (19), pp. 1–38.

Kuusaana E.D and Bukari, K.N. (2015) Land conflict between smallholders and Fulani herdsmen in Ghana: evidence from the Asante Akim North District. Journal of Rural Studies, 45, 52–62.

Kuusaana, E.D. (2016) Large-scale land acquisition for agricultural investments: implications for land markets and smallholder farmers. Doctoral dissertation. The University of Bonn.

Mbih, R. (2020) The politics of farmer–herder conflicts and alternative conflict management in Northwest Cameroon. African Geographical Review, 39 (4), pp. 324–344.

Moritz, M. (2006) The politics of permanent conflict: Farmer-herder conflicts in northern Cameroon. Canadian Journal of African Studies/Revue canadienne des études africaines, 40 (1), pp. 101–126.

Non-attributable comment, Opinion leader. November 2019. Ghana.

Non-attributable comment, settler farmer. November 2019. Ghana.

Non-attributable comment, settler farmer. November 2019. Ghana.

Non-attributable comment, nomadic herder. November 2019. Ghana.

Non-attributable comment, nomadic herder. November 2019. Ghana.

Non-attributable comments, settler famers. December 2019. Ghana.

Non-attributable comment, opinion leader. December 2019. Ghana.

Non-attributable comments, nomadic herders. December 2019. Ghana.

Olaniyan, A, Francis, M and Okeke-Uzodike, U. (2015) The Cattle are “Ghanaians” but the herders are strangers: farmer-herder conflicts, expulsion policy, and pastoralist question in Agogo, Ghana. African Studies Quarterly 15 (2), pp. 53–67.

Otu, B and Impraim, K. (2021) Aberration of farmer-pastoralist conflicts in Ghana. Peace Review. 33 (3), pp. 412-419.

Otu, B.O. (2022) Contestations and conflict over land access between smallholder settler farmers and nomadic Fulani cattle herdsmen in the Kwahu Afram Plains South District, Ghana. PhD thesis, Centre for African Studies, Cape Town, University of Cape Town.

Paalo, S.A. (2021) The politics of addressing farmer-herder conflicts in Ghana. Peacebuilding, 9

(1), pp. 79–99.

Reuveny, R. (2007) Climate change-induced migration and violent conflict. Political Geography. 26 (6), pp. 656–673.

Robbins, P. (2012) Political ecology: A critical introduction, (2nd ed.), Chichester, ENG: John Wiley and Sons Publishing.

Robbins, P. (2019) Political ecology: A critical introduction. (3rd ed.). New York: John Wiley & Sons.

Sarfo, K. (2011) The effect of land tenure on yam farming in the Atebubu traditional area. MPhil Thesis. Legon, University of Ghana.

Seddon, D and Sumberg, J. (1997) The conflict between farmers and herders in Africa: an analysis. Overseas Development Group, School of Development Studies, University of East Anglia, Project Summary, Norwich, UK.

Setrana, M. (2021) Citizenship, indigeneity, and the experiences of 1.5-and second-generation Fulani herders in Ghana. Africa Spectrum, 56 (1), pp. 81–99.

Tonah, S. (2002) The politics of exclusion: the expulsion of Fulbe pastoralists from Ghana in 1999/2000. Max Planck Institute for Social Anthropology Working Paper No. 44.

Tonah, S. (2005) Fulani in Ghana: migration history, integration, and resistance. Accra: Yamens Press.

Tonah, S. (2006) Migration and farmer-herder conflicts in Ghana’s Volta Basin. Canadian Journal of African Studies, 40 (1), 152–178.

Ubink, J and Quan, J. (2008) How to combine tradition and modernity? Regulating customary land management in Ghana. Land Use Policy. 25, pp. 198–313.

Wallis, J. R. (1953) The Kwahus—their connection with the Afram Plain. Transactions of the Gold Coast & Togoland Historical Society, 1 (3),

pp. 10–26.

Watts, M. (2000) Political ecology. In Sheppard E.S and Barnes, J.J. eds. A companion to economic geography. Malden, Mass: Blackwell.

Yeboah, I, Codjoe, S.I.A, and Maingi, J. (2013) Emerging urban system demographic trends: informing Ghana’s national urban policy and lessons for Sub-Saharan Africa.

Africa Today, 60 (1), 99–124. Yembilah, R and Grant, M. (2014) The political ecology of territoriality: territories in farmer-herder relationships in northern Ghana. GeoJournal, 79 (3), 385–400.