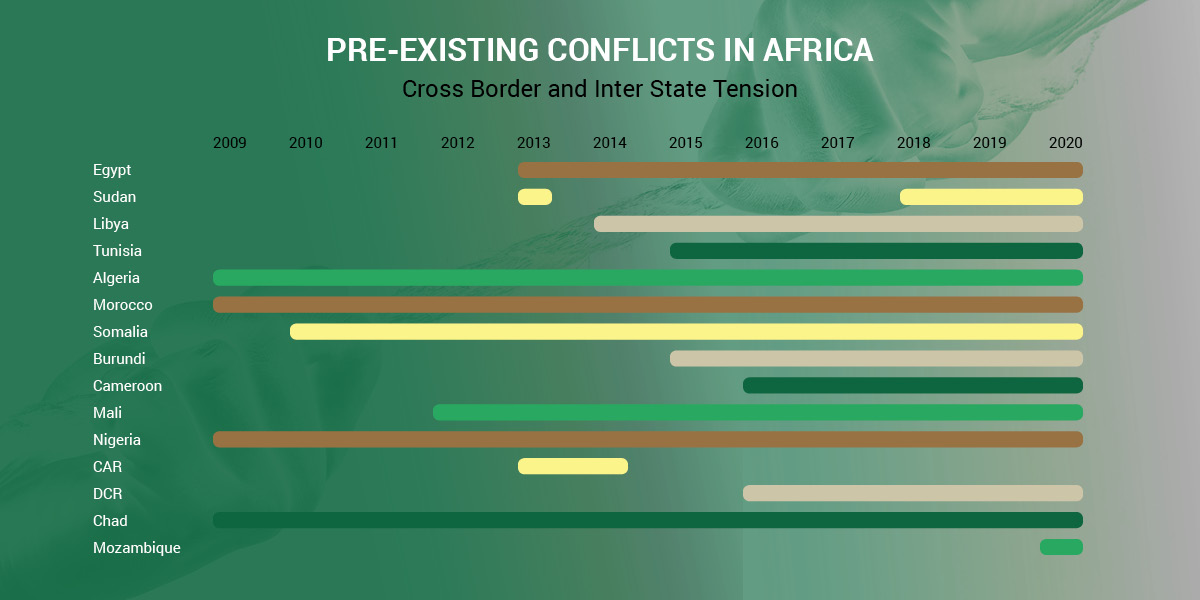

Border closures are not new in Africa. In 2019 countries such as Nigeria, Kenya, Rwanda, and Sudan closed their borders. Some cited security concerns related to terrorism and trafficking and the movement of rebel and insurgent groups as reasons for the closures. Rwanda closed its border with the DRC because of health concerns related to the spread of Ebola in Eastern DRC. Some borders were closed as a result of diplomatic and economic disputes. All the closures led to some level of inter-state tension.

What is different this time around with the COVID-19 pandemic, is the sheer scale of the closures, once it became known that COVID-19 was not restricted to China, where it originated, but that it could spread very rapidly by returning citizens, visiting tourists, or through cross-border trade. In an unprecedented move, along with most countries in the world, the majority of African countries almost simultaneously closed their land, sea, and air borders to contain the spread of the virus, by the middle of March 2020. The World Health Organisation (WHO) cautioned that the earliest a vaccine may be available will be between twelve to eighteen months, and that containment is currently the most viable strategy to mitigate the spread of the virus. Governments have heeded this caution, implementing national lockdowns and states of emergency as part of stricter mitigation and containment measures.

#C19ConflictMonitor: #COVID19 related cross-border incidents can result in a deterioration of relationships between states and in extreme cases in outbreaks of violence between states

Tweet

In China, a prolonged lockdown was immediately imposed in Wuhan, the original epicenter of the virus. The lockdown was lifted after 76 days when China was convinced that it had contained the spread of the virus. China later reported new infections which it claimed came from external and not local transmissions. Therefore, for African countries that may need to ease their restrictions on lockdowns and states of emergency, it may be more difficult to lift land, sea, and air border closures as the risks of getting external transmissions will be significantly higher.

Prolonged border closures, even possibly for intermittent periods, will probably become the norm for the foreseeable future while Governments continue to flatten the curve and manage the health and medical challenges posed by the lack of hospitals, medical personnel, medicines and other vital equipment such as respirators and ICU beds.

Weak health systems in many countries, and the shortage of medical supplies and personnel could have the impact of generating thousands of “health refugees” who could flee countries that are heavily impacted by the spread of the virus to get to countries that are not heavily impacted, or which have better medical facilities. Last year, as mentioned above, during the continuing Ebola crisis in the Eastern DRC, Rwanda closed its borders citing security concerns and an appeal was made by the World Health Organisation, on humanitarian grounds, for Rwanda to re-open its border, which it did. Countries will also have to consider the opening of borders to create humanitarian corridors and provide much needed disaster relief, should it become necessary. If countries resist, because of national security or health concerns, tensions will escalate at the inter-State and inter-communal levels.

While containment has become a universally adopted strategy and much is known about it, what is unknown is the unintended consequences of a prolonged closure.

In practice, border closures will generally mean the closure of formal border posts or immigration entry points. Outside of the formal border posts, most of Africa’s land borders are porous and the majority of Governments, including relatively stable nations, with a larger resource base, like South Africa, Nigeria, Egypt, and Morocco, find it difficult to effectively police their borders under ‘regular’ conditions. South Africa’s recent construction of a US$ 2 million fence, spanning forty kilometers, to prevent undocumented Zimbabwean nationals from crossing the border and to contain the spread of COVID-19, not only drew a sharp negative reaction from Zimbabwean authorities, but was damaged by criminal elements within days of being constructed. However, border closures are not an absolute deterrent for those who want to cross them and if they enter a country undetected and undocumented and if they are carriers of the virus their presence in a country can exacerbate the crisis.

In the fight against COVID-19 most countries are also deploying their military inside the country and especially in crowded urban areas, leaving their borders susceptible to the free movement of extremist and rebel groups, traffickers, and other negative forces. The strategic port of town of Mocimboa de Praia in Mozambique was taken by suspected Islamic State (IS) insurgents on 30 March 2020 where they symbolically hoisted their flag. Boko Haram launched a similar offensive in Chad on 30 March 2020, killing ninety-two Chadian soldiers, one of the worst attacks Chad has witnessed, and forty-seven Nigerian soldiers were ambushed and killed in north-eastern Nigeria by IS insurgents around the same time.

While it is not clear whether these incidents are directly related to the pre-occupation of security forces in the battle against the virus, IS has recently issued a statement calling on its followers to use the spread of the virus, and the space that it creates, to intensify its offensive.

The closure of the formal borders for an undetermined period will have a devastating impact on the millions of Africans who depend on cross-border trade for their livelihood and incomes, and will impact heavily on Informal Cross Border Trade (ICBT). According to John Stuart of the Trade Law Center (TRALAC), ICBT accounts for, “30-40% of total intra-regional trade in the SADC region and 40% in the COMESA region…individuals and firms that make up the market for ICBT are divided into individuals, informal businesses and formal businesses. The most vulnerable are the individuals and informal businesses. Of these, the majority of traders are women (60-70% as estimated by the African Development Bank)”.

In addition, the closure of borders that have a negative economic impact on one of the countries concerned has the potential to generate inter-State tensions which was the case, as stated above, with the closure of borders by several countries in 2019. Diplomatic tensions also arose between Morocco and the two Spanish enclaves of Ceuta and Melilla, whose economies depend largely on ICBT, when Morocco closed its border with the two enclaves in 2019, and which remains closed now to contain the spread of the virus, given the extremely high infection and fatality rates in Spain.

Nomadic pastoralism is another form of economic activity that will be seriously affected by border controls. It is practiced in different climates and environments with daily movement and seasonal migration. As we enter a seasonal change, and as the virus enters the phase of community infections, transhumance will become a major challenge in countries like the Central African Republic, Chad and the DRC where transhumance is not regulated. Should the virus spread rapidly within communities and it becomes necessary to curb the movement of transhumance, this may generate violent conflict.

Borders in Africa and their management are a factor of the complex socio-economic, political, environmental, and demographic challenges that Africa faces. The arrival of the Covid-19 pandemic has created a new and unprecedented challenge that can exacerbate existing vulnerabilities in Africa. Under ‘normal’ circumstances, terrorism, secessionism, trafficking, communal violence, land conflicts, smuggling, and cattle rustling are just some of the many challenges that confront African countries in managing their borders. A careful monitoring of existing vulnerabilities and the new challenges and stresses that COVID-19 will generate, and an analysis of how they manifest themselves and what the consequences will be, will allow the African Union, Regional Economic Communities and Regional Mechanisms, individual Governments, businesses and community-based organisations to prepare better to respond effectively to prevent and mitigate these potential conflicts.