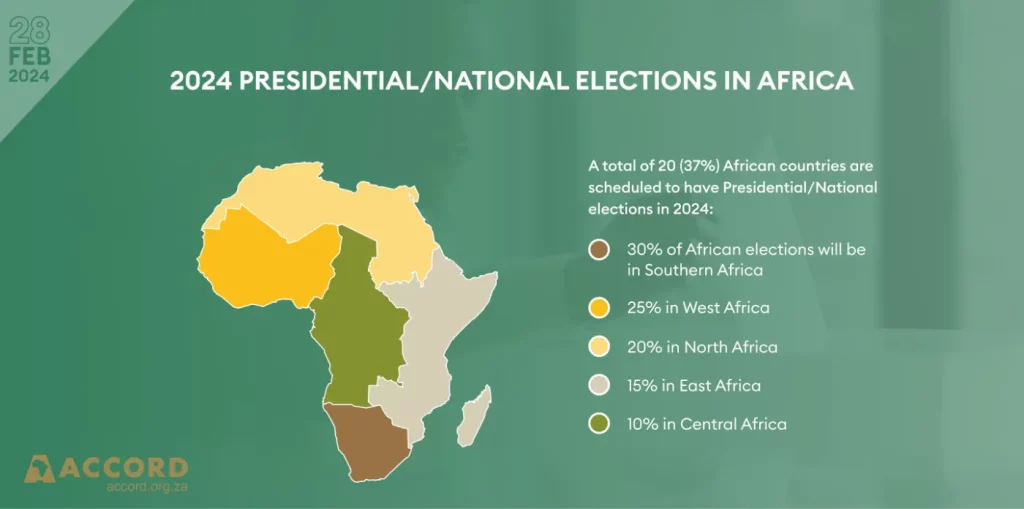

The year 2024 sees 20 African countries scheduled to have presidential/national elections. In other words, over 37% of African countries will be engaging in the democratic process of electing leaders to govern for the next electoral terms. The high number of elections makes it key to assess the Continent’s overall quality of governance and degree of democratic consolidation.

The large scale of elections poses both challenges and opportunities for the Continent’s political stability. Of the 20 elections, 30% will be in Southern Africa, 25% in West Africa, 20% in North Africa and 10% in Central Africa. The respective Regional Economic Communities (RECs) will be tasked with managing peace and security situations in the regions, and will also be involved in election observation missions to aid member states in conducting elections according to their Protocols and those of the African Union (AU).

The first, and only, election to be held thus far has been in Comoros on the 14th of January. The country’s electoral commission declared President Azali Assoumani the winner, with 62.97% of the vote. However, the Comoros Supreme Court validated that the President had actually won with 57.2% of the vote.

This fuelled perceptions from the opposition parties that the election may have been fraudulent. Subsequently, protesters took to the streets of Moroni (the capital city) on 17 and 18 January, with widespread destruction of property. The protestors were met by teargas and bullets from law enforcement authorities, with one person being killed, many sustaining gunshot wounds and others being arrested. A curfew was then announced on 18 January in attempt to quell the unrest.

The year 2024 sees 20 African countries scheduled to have presidential/national elections. In other words, over 37% of African countries will be engaging in the democratic process of electing leaders to govern for the next electoral terms.

Tweet

Another incident of election-related protests this year were in response to the postponement of the Senegalese presidential election. The election was scheduled for 25 February, but the President announced a postponement till December 2024 because of challenges with the selection of electoral candidates. Opposition parties expressed their disapproval of the postponement in parliament, alleging that the President was attempting to extend his term and delay the election. Subsequently, citizens staged protests in the capital city of Dakar to express their disgruntlement, which caused great political instability in the relatively stable West African country. The President has since changed his decision after a judicial intervention.

These two case studies depict the crucial importance of having elections being perceived as free and fair by both the winners and losers, and more especially, the citizens. The case studies also highlight the impact that elections can have on political (in)stability within the broader governance, peace and security nexus. While it would seem that the Continent is off to a rocky start to its election year campaign, these two cases must be viewed as serious early warnings for all stakeholders to contribute towards more peaceful and stable elections ahead.

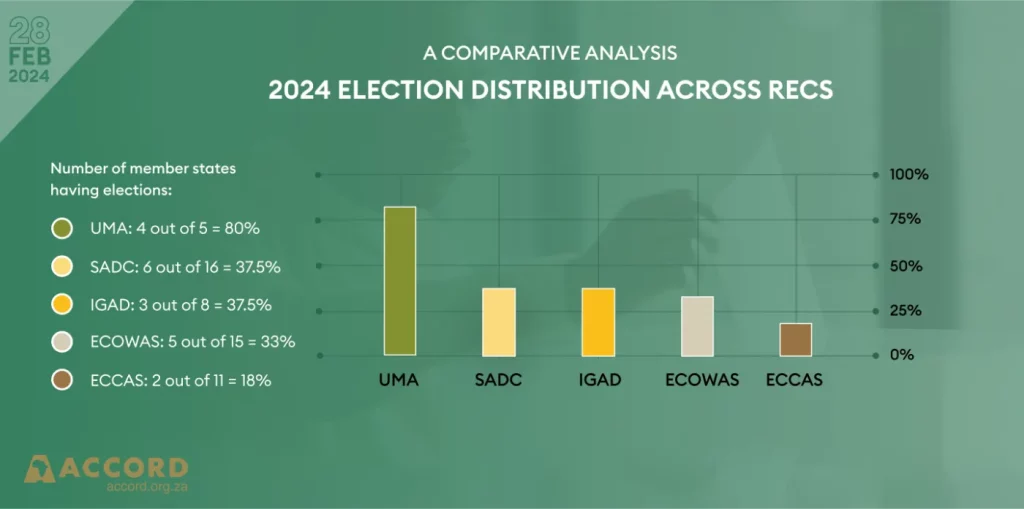

Looking at the regional distribution of Africa’s elections, the Arab Maghreb Union (UMA) has all but one of its member states heading to the polls this year, making it a ratio of 80% of its member states. Mauritania’s election will be conducted on 22 June; Algeria, Libya, and Tunisia are yet to finalise their respective election dates. The elections in Tunisia will be the first after President Kais Saied dissolved parliament in 2021 and reformed the Constitution. The Tunisian election will come against the backdrop of a shrinking civic space, and democratic decline, further accelerated by the President’s prohibition of international electoral observers. That being noted, Tunisia’s 2024 election provides an opportunity to restore democracy, not only in the country but across the UMA region, and muzzle rumours of a second Arab Spring.

The Southern African Development Community (SADC) will be hosting the largest number of elections, with six member states holding elections. With Comoros having completed their elections, Botswana, Mauritius, Mozambique, Namibia and South Africa await their turn. The SADC‘s Electoral Observer Mission (SEOM) and its Electoral Advisory Council (SEAC) will have to remain on high alert to monitor the upcoming elections in line with the SADC Principles and Guidelines on Elections, and reflect on possible conflict situations.

In the Intergovernmental Authority on Development (IGAD) region, Ethiopia, Somalia and South Sudan are aiming to host elections. Ethiopia will be hoping to make progress in consolidating political stability, after the November 2023 peace deal on the Tigray conflict, and at a time when a ‘state of emergency’ was extended earlier this month due to escalating violence in the Amhara region.

The Southern African Development Community (SADC) will be hosting the largest number of elections, with six member states holding elections.

Tweet

All eyes will be on the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS), with elections in Burkina Faso, Ghana, Guinea Bissau, Mali and Senegal. The ECOWAS is under immense pressure considering the resurgence of coups in West Africa. Added to that, the regional bloc is still dealing with the withdrawal of Burkina Faso, Mali and Niger and the implications thereof. While two of these nations are navigating a fresh post-coup political landscape, it remains to be seen whether Burkina Faso and Mali will complete their constitutional changes of government through democratic elections this year or whether there will be further postponements.

The Economic Community of Central African States (ECCAS) has only two elections out of the eleven member states. In both Chad and Rwanda, the sense is that little will change concerning the national leaders. Many are sceptical of the election in Chad, which has had elections promised and postponed since April 2021 when General Mahamat Deby took power. Similarly, the July election in Rwanda will most probably see Paul Kagame continue his Presidency.

As the Continent continues with its elections calendar, a few key things can make these ‘eventful’. Firstly, the increased electoral participation of Africa’s youthful population, and more young people being elected into positions of political power. Secondly, the enhanced role of election observer missions, whose activity will increase the checks and balances within domestic electoral processes. Thirdly, the AU and RECs must action rigorous preventative measures and decisive responses to undemocratic electoral practices that may cause civic unrest and political instability on the Continent in 2024.

Mr Nkanyiso Simelane is a Researcher within ACCORD’s Research Unit, focussing on the Governance, Peace and Security nexus.