National dialogues have emerged as crucial tools for conflict transformation, promoting inclusivity and consensus among various actors in internal conflicts. The recurrent escalation of socio-political and economic challenges – particularly in Africa – has advanced the use of national dialogues to calm tensions and foster the transition toward peace and reconciliation. Defined as formal and nationally owned processes that seek to solve problems of national relevance, national dialogues offer a forum for discussion among conflicting stakeholders and the state.1 In Africa, national dialogues have been organised in Kenya (2007), Côte d’Ivoire (2011), Tunisia (2013-2014), Sudan (2014), Burkina Faso (2024), Mali (2024), Chad (2024), Gabon (2024), and Niger (2025) to address post-electoral protests, intra-state conflicts, and coups, respectively. Scholars suggest that a successful national dialogue must have the following features: inclusivity, transparency and public participation, a credible and neutral convener, a clear agenda, and a feasible implementation timeline for its recommendations.2

Inclusivity guarantees that all key stakeholders, including marginalised groups, are represented in the dialogue process. By incorporating diverse perspectives, the dialogue gains legitimacy and addresses the main drivers of conflict. When participants perceive that their voices are heard, this enhances trust and commitment to the dialogue results. Dialogues that include women, youth, and other traditionally excluded groups are more likely to tackle key causes of conflict effectively.

Transparency entails open communication about the dialogue process, objectives, and results. This frankness aids in building public trust and facilitates broader societal participation. Public participation is crucial – when citizens are actively involved, they are more likely to support and commit to the dialogue’s recommendations, establishing a feeling of ownership over the process and its outcomes. Effective national dialogues often integrate mechanisms for keeping the public informed, even if they are not directly engaging in discussions.

A credible and impartial convener contributes significantly to facilitating dialogue. This entity should be trusted by all stakeholders and seen as neutral, thus safeguarding a fair process. A well-respected convener can mediate conflicts, balance power dynamics, and facilitate productive deliberations, improving the chances of attaining consensus. National dialogues’ effectiveness often relies on the credibility of their convener, as a perceived bias can compromise the entire process.

A clear programme summarises the themes to be discussed and the goals of the dialogue. It provides an organised basis that keeps discussions focused and fruitful. Well-defined goals help participants understand the purpose of the dialogue and the expected outcomes, which can inform their inputs effectively. Dialogues with a clear agenda are more likely to achieve meaningful results.

A feasible execution plan for recommendations is crucial for ensuring that the dialogue’s results are actionable. Without an accurate timeline, there may be interruptions or failures in implementing agreed-upon actions, resulting in disenchantment among stakeholders. A clear timeline establishes accountability and inspires continuous momentum toward achieving peace. Successful dialogues often include specific timelines for implementing recommendations, which helps maintain engagement and commitment from all parties involved.

Background to the Major National Dialogue

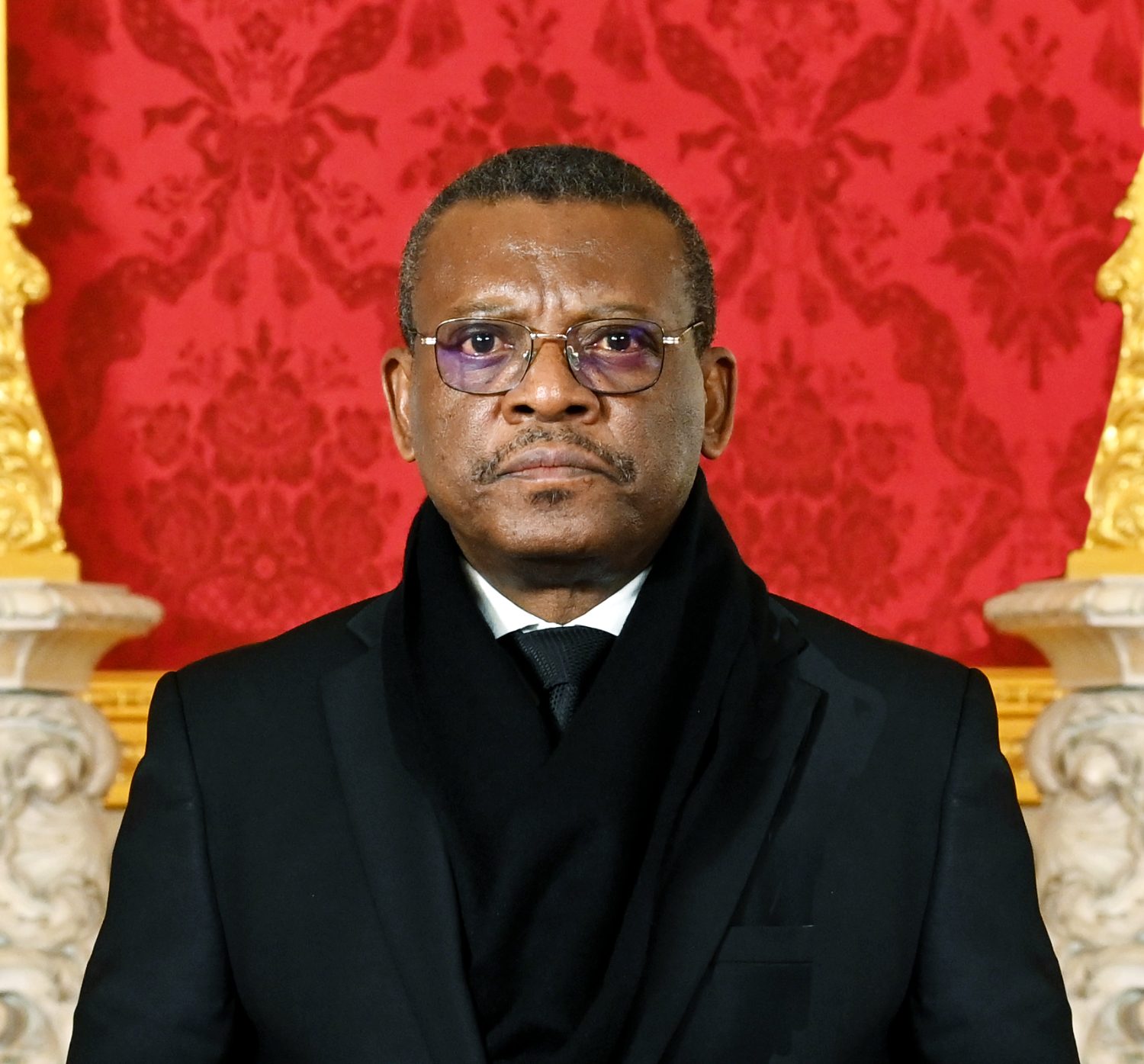

The Major National Dialogue (MND) was initiated in Cameroon in 2019 to address the armed conflict in the English-speaking regions, commonly known as the Anglophone crisis, as well as other socio-political challenges, including Boko Haram incursions in the Far North region. The ongoing Anglophone crisis, which escalated from a peaceful protest by teachers’ and lawyers’ trade unions in the Anglophone regions in 2016, has been marked by violence, human rights violations, humanitarian challenges, and entrenched grievances among the Anglophone population.3 The MND was convened by the head of state, Paul Biya, from 30 September to 4 October 2019, amidst a context of growing tensions stemming from feelings of linguistic marginalisation, demands for greater autonomy, and a perceived absence of representation in national governance by Anglophone Cameroonians. 4

The Cameroonian authorities designed the MND as a fundamental move towards national cohesion and stability, intending to involve a broad range of actors to address the key triggers of the Anglophone crisis and other socio-political issues plaguing the country. The MND was convened through a message to the nation on 10 September 2019, placed under the chair of the Prime Minister, to discuss eight main themes outlined by the convener, President Paul Biya. These themes included: bilingualism, cultural diversity and social cohesion; the education system; judicial system; return of refugees and internally displaced persons; reconstruction and development of conflict-affected areas; disarmament, demobilisation and reintegration of ex-combatants; the role of the diaspora in the crisis and in Cameroon’s development; and decentralisation and local development. The five-day event culminated in a series of recommendations, including those aimed at addressing the Anglophone crisis.

Despite the potential of national dialogues to promote peace and reconciliation, the effectiveness of the 2019 MND in Cameroon remains a factor of critical debate. While some stakeholders contend that it offered a framework for presenting grievances and recommending reforms, others suggest that it was devoid of fundamental elements of an effective national dialogue. This paper critically explores the strengths and challenges of the MND, examining its impact on the ongoing Anglophone crisis and assessing the broader implications for conflict transformation in Cameroon.

The strengths of the Major National Dialogue

One of the key strengths of the MND was its recognition of the grievances of the Anglophone population, i.e. the Anglophone problem. For decades, the Anglophone regions have expressed perceived marginalisation, including the dominance of the French language in official settings, and the abolition of the federal state in 1972, replacing it with a strong centralisation of power in the unitary state. Although the MND excluded discussions on the formation of the state, it did, however, acknowledge the Anglophone problem. This provided a forum for voicing grievances that had long been overlooked, which is essential for any genuine reconciliation process.

Furthermore, the MND ended with several proposals to provide greater autonomy to the Anglophone regions. Main results included proposals for political reforms, including a special status for the Anglophone regions, effective decentralisation, enhanced autonomy in all ten of the country’s regions, and a disarmament, demobilisation and reintegration (DDR) programme.5 These recommendations were applauded, with many Anglophones seeing them as a means of return to normalcy and improved participatory governance. The proposals were implemented through the adoption of a law in December 2019 on regional and local authorities. This law granted a special status to the Anglophone regions with the following features: a bicameral regional assembly composed of a divisional house of representatives and a house of chiefs for each of the regions, with members elected through indirect suffrage; and the institution of the Office of the Public Independent Conciliator for each of the regions to maintain cordial relations and address disputes between citizens and regional and local authorities.6 These institutional innovations were praised for their potential to bring decision-making closer to the constituents, enhancing responsiveness and accountability.

Moreover, the MND succeeded in giving more visibility to the Anglophone crisis at the international level. The Norwegian Refugee Council has described the conflict as one of the most neglected and underreported in the world.7 The engagement of civil society and some states brought the crisis global attention, increasing pressure on the Biya government to adopt actionable reforms and uphold human rights. This international exposure was critical in order to ensure that the MND’s recommendations were not just symbolic, but rather substantial reforms in governance and conflict resolution.

The momentum raised by the MND established a suitable platform for continued discussions among the various actors. Some loopholes recorded during the MND could be addressed by calling for further inclusive dialogue among the main stakeholders, including marginalised populations, to mitigate underlying tensions and promote a more inclusive context. This could leverage the commitment of the United Nations and other international institutions to support ongoing dialogue efforts and conflict transformation strides in Cameroon.

Challenges and weaknesses of the MND

The MND primarily aimed to address the Anglophone crisis and promote peace in Cameroon. However, several difficulties and weaknesses have emerged, undermining its effectiveness. These include a lack of genuine inclusivity, limited political will, implementation constraints, and poor public perception and trust.

Prominent stakeholders, including separatist leaders and pro-independence Anglophone activists, were visibly absent from the discussions due to their incarceration or exile.8 This was contrary to the government’s claim to have engaged various stakeholders in the process. This exclusion provoked interrogations about the dialogue’s legitimacy, resulting in extensive scepticism among stakeholders who considered their voices unrepresented. Consequently, the dialogue was perceived as more of a government-manipulated endeavour than a genuine participatory process. Some critics labelled the dialogue a government monologue in which the agenda and proceedings were largely imposed by the state, with minimal opportunity for meaningful input from participants.9 Some opposition leaders criticised the entire process, with the Cameroon Renaissance Movement boycotting it, while the Social Democratic Front conditioned its participation on a ceasefire and an amnesty for all detained due to the conflict, and that a neutral third party chair the MND.

The effectiveness of the MND has also been challenged by insufficient political will from the Cameroonian government to commit to a genuine and sustained peace process. The government’s inconsistency towards third-party mediation offered by Switzerland and Canada demonstrates an unwillingness to fully engage with inclusive dialogue that responds to the key sources of conflict. While the Cameroonian government at the outset declared the MND a success, the enduring violence and human rights violations in the Anglophone regions highlight a detachment between dialogue rhetoric and reality. The government’s intentions and the genuine nature of its resolve for peace have been questioned, with critics contending that government manoeuvres were inconsistent with its promises.10 This has created further disillusionment among Anglophone Cameroonians who had hoped for substantive reforms.

The MND adopted several recommendations to resolve the Anglophone crisis; however, the enforcement of these resolutions has encountered multiple constraints. The implementation of some recommended reforms on decentralisation, enhanced autonomy for the Anglophone regions, and improved bilingualism has not met citizens’ expectations. The special status institutions in the two regions constitute a façade of autonomy, as the Regional Assemblies cannot take decisions on key issues without the approval of the Regional Governor, appointed by the Head of State.11 Despite creating the National Commission on the Promotion of Bilingualism and Multiculturalism to address bilingualism challenges, the French language continues to dominate in certain public offices in the Anglophone regions. Moreover, the activities of the Public Independent Conciliators in the two regions have been restricted to fact-finding and publication of reports and recommendations, without compelling powers to ensure the implementation of their decisions. The lack of meaningful autonomy desired by many Anglophones has nurtured a feeling that the MND was more about addressing disagreements than promoting genuine reforms.

The perception of the MND among the Anglophone population has been mixed, with many viewing it as a superficial initiative rather than a sincere effort to resolve the conflict.12 The failure to achieve meaningful progress in addressing the concerns raised by Anglophone activists has undermined trust in the state and its institutions. Some stakeholders perceive the MND as being heavily manipulated by the government, which erodes the facilitators’ perceived neutrality and the overall credibility of the process. Excessive government control has restricted open dialogue and inclusive participation, further entrenching divisions rather than enhancing social harmony and sustainable peace. Civil society organisations and opposition leaders have expressed concerns that without a credible and inclusive dialogue process, violence, destruction, and atrocities in the Anglophone regions will continue.13

The implications of the Major National Dialogue

The MND, convened in 2019, aimed to address the protracted Anglophone crisis that has significantly impacted Cameroon’s socio-political scene. In the immediate aftermath, the MND promoted discussions among various stakeholders, including the government, opposition, civil society, clergy, and traditional authorities. Nevertheless, this inclusivity was undermined by the absence of the main separatist factions, who felt isolated from the process. Their absence triggered doubts about the dialogue’s legitimacy, with some citizens and stakeholders perceiving it as a superficial government-manipulated process framed to placate opposition rather than foster genuine reconciliation. This scepticism was further exacerbated by enduring violence in the Anglophone regions, six years after the MND, where confrontations between government forces and secessionists continue unabated, compromising trust in the government’s resolve for peace.

An analysis of the MND reveals that while resolutions were adopted from the discussions – such as enhanced regional autonomy, bilingualism, and effective decentralisation – enforcement has been slow and inconsistent. The government’s commitment to implementing the MND’s recommendations has been sluggish, reinforcing disillusionment among Anglophones.14 Most of these proposals and other measures to address the conflict have remained on paper, without a substantial impact on the population. For instance, most localities in the Anglophone regions continue to endure violence, kidnappings, extrajudicial killings, economic instability, school closures, and inadequate basic public service delivery. The persisting insecurity highlights the ineffectiveness of the MND in addressing the root causes of the Anglophone crisis, presenting the need for a more frank and inclusive dialogue. This situation reflects scenarios in other African contexts, such as South Sudan, where the 2016 dialogue has encountered challenges with inclusivity and implementation, further exacerbating conflict.

Moreover, the MND in Cameroon presents similar features to some unsuccessful dialogue initiatives in other African countries, as opposed to successful cases. For instance, the post-Arab Spring Tunisian national dialogue has been praised for its genuine inclusivity, resulting in a new constitution and the implementation of a more participative political framework. This mirrors South Africa’s political transition from apartheid through broad dialogue processes that engaged an extensive range of stakeholders, resulting in a peaceful transition.15 Conversely, the Cameroonian and South Sudanese dialogue processes struggle with elite-based approaches and restricted engagement of key stakeholders. The South African and Tunisian experiences inform Cameroon of the significance of integrating a broader spectrum of actors and the effective implementation of resolutions, to enhance legitimacy and ensure that peace endeavours are consistent with the population’s desires.

Conclusion

The MND in Cameroon is a critical example for understanding the intricacies of national dialogues in conflict transformation. Its analysis highlights that while it sought to address the Anglophone crisis, its success has been critically compromised by issues of inclusivity, implementation constraints, and poor popular perception. Main stakeholders in the conflict – separatist groups – were not part of the discussions, raising scepticism about the dialogue’s legitimacy and outcomes. This exclusion resonates with arguments that successful national dialogues require genuine engagement of all actors to enhance legitimacy and trust in the entire process and implementation of recommendations.16

Moreover, the MND’s slow and inconsistent enforcement of resolutions has perpetuated disenchantment among the Anglophone population, worsening tensions rather than mitigating them. The failure to transform the dialogue’s proposals into substantive reforms and transformative projects emphasises a significant gap in the process, aligning with other contexts such as South Sudan, where similar endeavours failed due to a lack of follow-up.

Looking forward, the prospects for subsequent dialogue efforts in Africa centre on the lessons learnt from the MND. As highlighted above, an exemplary national dialogue should prioritise inclusivity and sincere involvement of all stakeholders, including marginalised communities. Adopting robust and participative mechanisms for monitoring and implementing the resolutions is essential for building public trust and guaranteeing sustainable peace. Through these principles, national dialogues have the potential to transform conflicts and promote democratic governance.

Robert Kosho Ndiyun is a Post-Doctoral Research Fellow in the Department of Public Management at Tshwane University of Technology, South Africa, working on state capacity building in conflict and post-conflict states. His research interests include transitional justice, peace and conflict studies, human rights and gender in Africa.

Endnotes

1Mandikwaza, E. (2024) ‘A conceptual framework for national dialogues: Applied theories and concepts’, African Journal on Conflict Resolution, 24(2), 7–28.

2Ibid.

3Beseng, M.; Crawford, G.; and Annan, N. (2023) ‘From “Anglophone problem” to “Anglophone conflict” in Cameroon: Assessing prospects for peace’, Africa Spectrum, 58(1), 89–105.

4Fuh, N. V. (2024) ‘An appraisal of the Major National Dialogue as a panacea to the Anglophone crisis in Cameroon’, Journalism, 14(1), 31–51.

5Beseng, M. et al. (2023) ‘A conceptual framework for national dialogues’, op. cit.

6Ndiyun, R. K. and Mukonza, R. M. (2025) ‘Cameroon: Façade of autonomy? The special status as a solution to the Anglophone crisis’, Conflict Studies Quarterly, 50, 72–94.

7Mutah, J. (2022) ‘Global responses to Cameroon’s Anglophone crisis: The inadequate international efforts to end the world’s most neglected conflict’, The SAIS Review of International Affairs, Available at: https://saisreview.sais.jhu.edu/cameroon-anglophone-crisis-global-response (Date accessed: 12 April 2025).

8Beseng, M. et al. (2023) ‘A conceptual framework for national dialogues’, op. cit.

9Kinkoh, M. M. and Begealawuh, N. C. (2023) ‘Beyond power politics: Are there any prospects for a successful peace-building dialogue in Cameroon?’, Available at: https://onpolicy.org/beyond-power-politics-are-there-any-prospects-for-a-successful-peace-building-dialogue-in-cameroon (Date accessed: 12 April 2025).

10Fuh, N. V. (2024) ‘An appraisal of the Major National Dialogue’, op. cit.

11Ndiyun, R. K. and Mukonza, R. M. (2025) ‘Cameroon: Façade of autonomy?’ op. cit.

12Ibid.

13International Crisis Group (2023) ‘A second look at Cameroon’s Anglophone Special status’, Briefing No. 188, 31 March, Available at: https://www.crisisgroup.org/sites/default/files/2023-03/b188-cameroon-anglophone-special-status_1.pdf (Date accessed: 14 April 2025).

14Begealawuh, N. C. (2024) ‘Missed or misused opportunity? Social cohesion, national dialogue and peacebuilding in Cameroon’, African Security Review, 33(4), 497–513.

15Maharaj, M. and Jordan, Z. P. (2021) Breakthrough: The struggles and secret talks that brought apartheid South Africa to the negotiating table, Johannesburg: Penguin Random House.

16Inclusive Peace (n.d.) ‘National Dialogues and politicisation: Peers and practitioners experiences from across the globe’, Available at: https://www.inclusivepeace.org/national-dialogues-and-politicisation (Date accessed: 17 April 2025).