In the past two decades, national dialogues have become a recurring feature in post-conflict transitions and governance reform across Africa. These processes are often convened to respond to crises of legitimacy, protracted violence, or political fragmentation. While national dialogues are widely acknowledged as participatory mechanisms intended to rebuild social contracts and create pathways for peaceful political transitions, their outcomes have often been mixed. Some have helped usher in new constitutional orders or restore relative stability, while others have collapsed due to elite manipulation, the exclusion of key stakeholders, or a lack of follow-through on agreed-upon resolutions. Despite growing attention from international organisations and regional bodies, such as the African Union (AU) and the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS), many national dialogues remain vulnerable to a key limitation: a failure to ground the process in locally legitimate and culturally resonant frameworks of dialogue and consensus-building.[1]

One of the critical yet overlooked dimensions in the design of national dialogues in Africa is the limited incorporation of anthropologically grounded approaches to conflict resolution. Indeed, in many instances, these dialogues replicate procedural blueprints modelled on Western liberal notions of deliberation, often emphasising electoral legitimacy, adversarial bargaining, or constitutional legality. However, these externally driven frameworks usually ignore the rich and deeply rooted traditions of communal dialogue, reconciliation, and restorative justice in African societies. As scholars and peace practitioners have increasingly observed, successful peace processes in Africa require not only institutional inclusiveness but also cultural intelligibility.[2] A national dialogue that resonates with local modes of reasoning and social organisation is more likely to secure legitimacy, mobilise trust, and foster sustainable reconciliation.

This article, therefore, draws from indigenous African worldviews to reimagine national dialogues as more than elite negotiation forums or procedural frameworks. It situates the palaver tree, a central symbol and practice of African communal deliberation, as a foundational technology of conflict resolution. The palaver tree, present in diverse cultures from the Igbo and Yoruba in Nigeria to the BaKongo and Fang in Central Africa, and among the Shonas in Zimbabwe, functions as both a physical space and an epistemic practice for resolving disputes, sharing grievances, and restoring broken relationships.[3] At its core, the palaver system emphasises oral negotiation, consensus-building, participation of elders and women, and truth-telling for social restoration. It is not merely a tool of informal governance, but a deeply rooted moral and social institution that reflects African ontologies of personhood, community, and justice.[4]

In this vein, the article introduces and develops two conceptual innovations grounded in the palaver tradition: the national tribunal and the republican confessional. The national tribunal refers to an inclusive, non-adversarial forum where competing political actors, civil society groups, and communities engage in a frank, structured, ritualised dialogue to address national grievances. Unlike conventional judicial tribunals, it prioritises consensus over litigation and restoration over punishment.[5] The republican confessional, in turn, is a dialogic mechanism modelled on the confessional logic of truth-telling and moral responsibility found in African rites of reconciliation. It allows individuals or groups to acknowledge publicly the harms they have committed, express remorse, and seek social reintegration through communal forgiveness. This mechanism, unlike the truth commissions of liberal democracies, embeds moral accountability within the civic space rather than outsourcing it to professionalised bureaucracies or external observers.

Together, these concepts build on the ancestral logic of the palaver tree to offer a re-Africanised grammar for national dialogue — one that restores the epistemological sovereignty of African societies in designing their own peace infrastructures. Rather than romanticising tradition, the article engages with the palaver tree and its institutional derivatives as evolving and adaptable technologies capable of informing hybrid governance arrangements that bridge indigenous and modern systems. Ultimately, the introduction of the national tribunal and republican confessional reaffirms the proposition that peace in Africa cannot be sustained through procedural imports alone; it must be cultivated through culturally embedded,[6] dialogic ecosystems of trust.

The palaver tree: An African conflict resolution technology

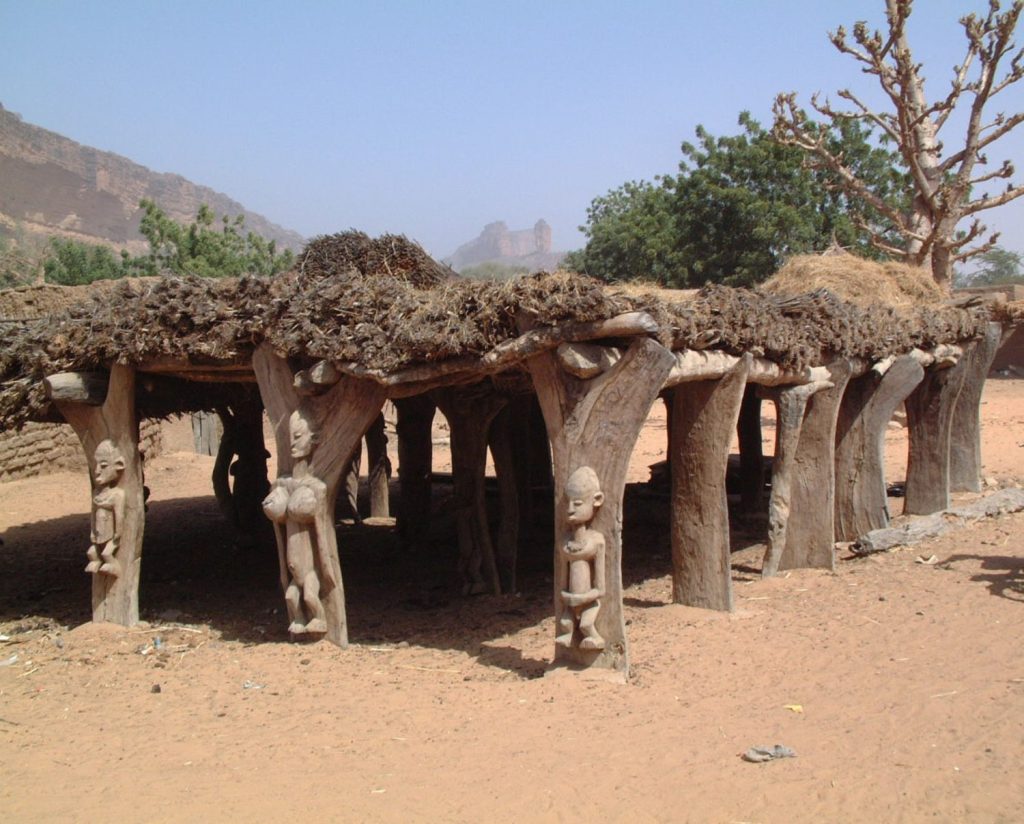

The palaver tree represents a living institution rooted in communal epistemologies, customary practices, and oral political traditions across the continent. From the Akan of Ghana and the Fang-Beti and Bantu communities of Central Africa to Sahelian societies, such as the Dogon and Fulani, the palaver tree serves as both a physical gathering site and a moral universe in which disputes are managed, truth is told, and relationships are mended. Often located under a large baobab or iroko tree in village centres, it offers a culturally sanctioned space where elders, chiefs, lineage heads, women, and youth engage in participatory deliberations on matters ranging from land disputes and succession conflicts to marital grievances and communal offences.[7]

More specifically, ethnographic research demonstrates, for instance, that the Akan model is a practical manifestation of the African palaver approach, both in its structure and philosophy;[8] indeed, it operates, with firm reference to Ancestors and the Gods, under the authority of elders in a format that mirrors traditional palaver sessions. Disputes are not resolved through binary win-lose verdicts, but through extended deliberations aimed at preserving social cohesion. Similarly, among Fang communities in Cameroon and Gabon, the Tso’o or Tsogo ritual gatherings facilitate both spiritual reconciliation and legal pronouncements through physical and spiritual purification rooted in ancestral legitimacy.[9] In the Sahelian zone, conflict resolution often occurs through seasonal assemblies where orators and griots guide the collective memory and moral reasoning of communities, emphasising reconciliation over retribution. Ultimately, following the Ubuntu principle, the paramount goal is not to let the offence sever the sacred bond between an individual and the community.[10]

What binds these practices is a set of normative principles that distinguish the palaver tree from adversarial models of justice. The first is consensus (palabre en consensus), which implies that decisions are only binding when all parties, even the marginal ones, express agreement, either actively or through silence understood as consent.[11] This consensus-seeking process can be lengthy, as it involves listening, repetition, storytelling, and the invocation of ancestral wisdom, but it ensures that solutions are socially sustainable. The second core principle is communal truth; unlike in Western legal traditions, where objective, factual truth is established through evidence and cross-examination, the African palaver seeks a truth that resonates with the collective understanding of the community, shaped by memory, morality, and relational context.[12] The third is restoration, wherein the goal is not to punish the offender, but to reintegrate them into the moral fabric of society through reparations, symbolic gestures, and communal forgiveness.[13]

These principles sharply contrast with the liberal-democratic negotiation models prevalent in international peacebuilding and national dialogue frameworks. Liberal models often centre around formal institutions, legal codification, time-bound agendas, and the prioritisation of individual rights. Dialogue in this tradition is frequently procedural and elite-driven, privileging stakeholders who possess formal political legitimacy or electoral capital. In contrast, the palaver model is non-hierarchical, inclusive of authorities outside formal state structures, and sensitive to local cosmologies and oral knowledge systems.[14] While liberal frameworks pursue justice through law and rights adjudication, the palaver system emphasises relational justice, meaning that it stresses the healing of social bonds over the protection of legal entitlements.[15]

In contemporary applications, this contrast is not merely theoretical. Studies show that many post-conflict societies that rely solely on formal negotiations without embedding indigenous dialogue methods often suffer from relapse into conflict or superficial reconciliation. In Liberia and Sierra Leone, for instance, the marginalisation of traditional elders and community forums in favour of externally designed truth commissions led to public perceptions of alienation and procedural injustice.[16] Conversely, where traditional mechanisms were integrated, such as the Gacaca courts in Rwanda or the Bashingantahe councils in Burundi, the results showed higher levels of community engagement and moral satisfaction, despite some procedural limitations.[17]

Thus, the palaver tree, while ancient, is neither obsolete nor symbolic. It offers an alternative technology of governance, one that centres voice, belonging, and social repair in ways that formal systems often overlook. Reclaiming this tradition in national dialogues does not mean rejecting liberal institutions but rather hybridising them with culturally embedded mechanisms that resonate with African ontologies of peace and justice. By doing so, the palaver tree can be transformed into an institutional backbone of future national tribunals and republican confessionals that reflect both the lived realities and moral aspirations of African societies.

The palaver tree and the notions of national tribunal and republican confessional

As Africa continues to grapple with post-conflict transitions, contested state-building processes, and fragile national identities, there is growing urgency to rethink peace infrastructures through endogenous lenses. Within this intellectual and policy imperative, the palaver tree not only serves as a symbolic anchor of African deliberative traditions but also inspires new institutional imaginaries that can be mobilised and conceptualised in formal governance systems. Two such institutional innovations — the national tribunal and the republican confessional — emerge as dialectical components of the palaver tree, embodying its epistemological and dialogical foundations.

The national tribunal: A deliberative space of civic re-legitimation

The national tribunal is conceptualised as a hybrid and participatory institution rooted in the palaver logic but scaled to the national level. The system builds upon the traditional village council or assembly of notables (as seen in Bantu, Akan, and Sahelian societies), where collective deliberation is employed to resolve disputes, restore order, and establish communal values. Additionally, the tribunal is designed to be an inclusive and participatory platform, bringing together all ethnic, linguistic, religious and regional communities as equal stakeholders in the nation. Its objective would be to reveal and unfold historical grievances, from colonial injustices to inter-communal conflicts and state repression. Unlike formal judicial or parliamentary structures, the national tribunal does not function primarily through codified law or partisan contestation. Instead, it operates as a non-adversarial civic space, where diverse societal actors, including state representatives, traditional authorities, civil society, youth, religious leaders, and marginalised communities, are invited to engage in open-ended, structured dialogues that aim for consensus rather than majority imposition.[18]

Moreover, the tribunal’s authority is not derived from formal legal mandates, but rather from symbolic legitimacy and moral credibility, much like the elder-based systems of the palaver tree.[19] In practice, it could be institutionalised through constitutional or legislative instruments, but its essence would lie in the ritualisation of civic listening, collective memory, and inclusive reasoning, all of which are intrinsic to the palaver tree.[20] The tribunal is thus not a substitute for legal or parliamentary bodies but a complementary democratic organ oriented toward repairing broken social contracts in contexts of trauma, exclusion, or national fracture. One can observe embryonic forms of the national tribunal in some past African experiences, such as the 2015 Bangui National Forum in the Central African Republic (CAR).[21] In fact, this forum temporarily convened warlords, civil society representatives, and community leaders to articulate shared national values and chart a common path to peace. However, such forums often lack institutional continuity or cultural legitimacy because they are embedded in Western procedural logic or paradigms. Hence, a truly African national tribunal, inspired by the palaver tradition, would ritualise dialogue as an act of civic regeneration, not merely crisis management. Complementary to the national tribunal is the republican confessional.

The republican confessional: A space for moral accountability and social reintegration

Parallel to the national tribunal, the republican confessional is conceived as a civic-ritual mechanism through which individuals or groups involved in wrongdoing, whether political, moral, or criminal, can voluntarily enter a process of truth-telling, remorse, and symbolic reparations before the nation. While inspired in part by traditional confessional rites found in African customary justice systems (e.g., Tshiota rituals among the Luba people in the Kasai Central in DRC, the Tso’o ritual ceremonies among the Fang-Beti in Central Africa),[22] this innovation situates the confessional act within the republican space, thereby fusing moral accountability with civic responsibility. Unlike liberal truth commissions that often outsource the process of justice to expert panels or international observers, the republican confessional is radically performative and dialogic, allowing wrongdoers, such as politicians, military actors, or civilians, to publicly acknowledge their actions in a setting where the community can hear, respond, and offer moral judgment. This confession is not merely a testimonial, but also therapeutic, as it reconstitutes the offender’s link to the political community through humility, accountability, and symbolic atonement.[23]

Ultimately, the goal here is not punitive justice but reintegrative justice, as the offender is not banished from the public sphere but reinvited through a process of communal forgiveness, provided the offence is not appalling, the confession is sincere and accompanied by reparative actions. This mirrors the ethos of many palaver tree ceremonies, where healing is achieved not by silencing the past but by narrating it within a shared ethical framework.[24] It also challenges the amnesia often promoted by political elites, replacing it with deliberate remembrance grounded in moral reconciliation. The republican confessional, therefore, enacts a politics of dignity where victims and perpetrators, elites and citizens, are summoned to co-construct the nation’s ethical future. Moreover, its civic power lies in converting individual guilt into collective healing, while reinforcing the principle that public office, whether traditional or republican, must be morally accountable to the community it serves.

Conclusion: Toward a dialectic structure rooted in sub-Saharan African civilisational epistemologies

Both the national tribunal and the republican confessional are more than institutions; they are dialectical mechanisms that mirror the complementary logics of the palaver tree. The national tribunal ensures the collective mediation of structural grievances, while the republican confessional addresses the personal and interpersonal dimensions of moral rupture. Together, they constitute a dual-track model of national dialogue, capable of addressing both the macro-political and micro-ethical sources of conflict. They draw from African epistemologies that privilege relational harmony over institutional finality, voice over verdict, and truth with healing over truth with punishment.[25] Finally, in a context where postcolonial African states are still grappling with the legacy of externally imposed governance models, these innovations offer an authentic re-Africanisation of political dialogue, grounded in ancestral wisdom yet responsive to contemporary challenges. Thereof, by formalising the philosophy of the palaver tree in modern national institutions, Africa can cultivate a democratic future that is not only procedurally valid but culturally legitimate and morally restorative.

Dr Jean Yves Ndzana Ndzana holds a PhD in Governance and Global Affairs from Leiden University, Netherlands. He also has a Master’s and Bachelor’s in Peace and Development Studies from the Protestant University of Central Africa, Cameroon.

References

[1] De Coning, C. (2006) The future of peacekeeping in Africa. Conflict Trends, (3), 3–7.

[2] Murithi, T. (2006) Practical peacemaking wisdom from Africa: Reflections on Ubuntu. Journal of Pan African Studies, 1(4), 25–34.

[3] Zartman, I. W. (ed.) (2008) Traditional Cures for Modern Conflicts: African Conflict “Medicine”, London: Lynne Rienner Publishers.

[4] Mbiti, J. S. (1990) African Religions and Philosophy, 2nd edition, Oxford: Heinemann.

[5] Paul, T. S., Noye, K. P., and Jah, E. A. (2023) Comparative analysis of traditional African and Western peacebuilding. Wukari International Studies Journal, 7(4), p.12.

[6] Moseley, W. G., and Otiso, K. M. (Eds.) (2023) Debating African issues: conversations under the palaver tree (p. 26). New York: Routledge.

[7] Bohannan, P. (1957) Justice and Judgment among the Tiv, London: Routledge.

[8] Zartman, I. W. (ed.) (2008) Traditional cures for modern conflicts: African conflict “medicine”, op. cit.

[9] Laburthe-Tolra, P. (1975) Un tsógó chez les Eton. Cahiers d’études africaines, 15(59), 525–540.

[10] Scheid, A. F. (2011) Under the palaver tree: community ethics for truth-telling and reconciliation. Journal of the Society of Christian Ethics, 31(1), 17–36.

[11] Murithi, T. (2006) Practical peacemaking wisdom from Africa, op. cit.

[12] Zartman, I. W. (ed) (2008) Traditional Cures for Modern Conflict, op. cit.

[13] De Coning (2006) ‘The future of Peacekeeping in Africa’, op. cit.

[14] De Coning (2006) Ibid.

[15] Tuso, H. (2011) ‘Indigenous process of conflict resolution: neglected methods of peacemaking by the new field of conflict resolution’, In: T. E. Matyok (Ed.), Critical issues of peace and conflict: theory, practice and Paedagogy, Lanham, MD: Lexington Books, pp. 245–271.

[16] Huyse, L. and Salter, M. (2008) Traditional Justice and Reconciliation after Violent Conflict: Learning from African Experiences, Stockholm: International IDEA.

[17] Ingelaere, B. (2009) ‘Does the truth pass across the fire without burning? Transitional justice and its discontents in Rwanda’s Gacaca courts’, Discussion paper 2007.07, Institute of Development Policy and Management.

[18] Zartman I. W. (ed) (2008) Traditional Cures for Modern Conflict, op. cit.

[19] Faure, G-O (2011) ‘Le traitement négocié du conflit dans les sociétés traditionnelles’ [‘The negotiated settlement of conflict in traditional societies’], Négociations, 15(1), 71–87.

[20] Murithi (2006) ‘Practical peacemaking wisdom from Africa’, op. cit.

[21] Copley, A., & Sy, A. (2015, May 15). Five takeaways from the Bangui Forum for National Reconciliation in the Central African Republic. Brookings. Accessed from https://www.brookings.edu/articles/five-takeaways-from-the-bangui-forum-for-national-reconciliation-in-the-central-african-republic/ [Accessed: May 23, 2025].

[22] Laburthe-Tolra, P. (1975). Un tsógó chez les Eton, op. cit.

[23] Huyse and Salter (2008) Traditional Justice and Reconciliation, op. cit.

[24] Mbiti (1990) African Religions and Philosophy, op. cit.

[25] Tuso (2011) ‘Indigenous process of conflict resolution’, op. cit.