National dialogues can provide continental and regional actors with entry points to manage political and electoral violence through multi-track diplomacy. Multi-track diplomacy refers to the expansion of international engagement to a multiplicity of levels outside of the traditional diplomatic high-level channels. Multi-track diplomacy is linked to the whole-of-society approach to conflict management. This approach promotes adopting inclusive strategies to transform complex and multi-dimensional conflicts.[1] This shifts the focus away from traditional, high-level engagement among heads of states, diplomats and high-ranking officials. Multi-track diplomacy instead engages multiple conflict stakeholders in coordinated multi-level dialogues. Multi-track diplomacy in Africa translates into regionalising national dialogues because mediators deployed by the African Union (AU) and regional economic communities (RECs) engage with conflict actors largely within state-organised or, at the least, state-sanctioned frameworks. The East African Community’s (EAC) intervention during the Burundi political crisis from 2015 to 2019 demonstrates the opportunities and challenges presented by regionalising national dialogues in peace processes.

Burundi’s political crisis was triggered by the presidential candidate nomination of Pierre Nkurunziza by the National Council for the Defence of Democracy – Forces for the Defence of Democracy (CNDD-FDD). The CNDD-FDD’s decision caused a political crisis leading to large-scale protests, government crackdowns, an attempted coup d’état, and militia attacks on military garrisons. By 2018, the United Nations High Commission for Refugees (UNHCR) reported that over 430 000 refugees had fled the country due to the crisis.[2]

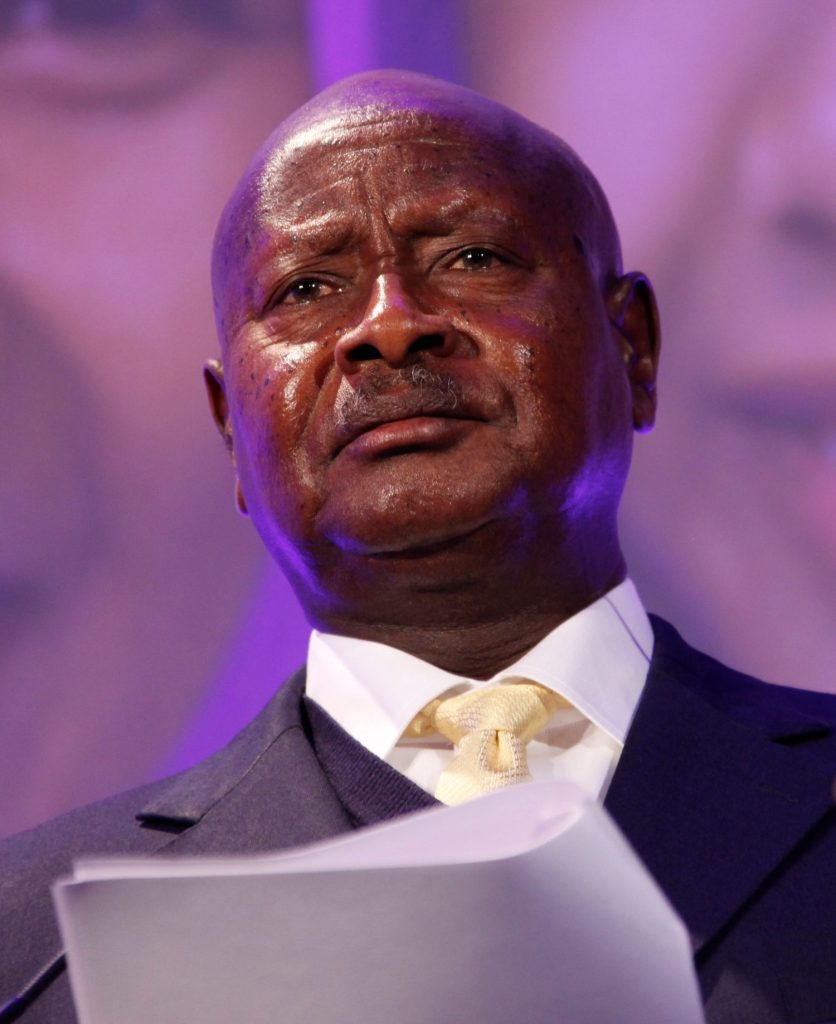

The EAC’s Inter-Burundi Dialogue eventually emerged as the main preventive diplomacy intervention with Tanzania’s late former president, Benjamin Mkapa, as the facilitator and Uganda’s president, Yoweri Museveni, as the chief mediator.[3] The Inter-Burundi Dialogue was conducted as a series of multi-track problem-solving workshops between December 2015 and October 2018. The problem-solving workshops were categorised into ecumenical, women, youth, political parties, and business leaders. The initiative ended with the attendees signing non-violence pacts. Additionally, Benjamin Mkapa held consultative meetings with a wide range of actors, from grassroots to high-level government officials and international actors, before each round of the main dialogue.

This article looks at how the Inter-Burundi Dialogue provides insights into how crackdowns on civic spaces, lack of formal regional citizen engagement channels, and government’s lack of cooperation complicate attempts to regionalise national dialogues. The article draws upon my PhD research,[4] which examined the role of regional organisations in promoting citizen participation in election violence prevention processes in Africa, and included 35 in-depth interviews with officials from intergovernmental organisations, civil society representatives in Burundi and expert sources.

Benjamin Mkapa, as the facilitator. Photo: Aly Ramji/Mediapix

and October 2018. Photo: UK Department for International Development.

Burundi’s shifting civic space

The EAC’s inability to influence the shifts in Burundi’s civic space during the course of the Inter-Burundi Dialogue showcases the challenges regional actors face in utilising national dialogues to resolve political crises. Prior to the 2015 elections and during the initial phases of the Inter-Burundi Dialogue, the country had well-developed civil society structures. Consequently, this provided adequate structures for multi-track diplomacy engagement between regional and local non-state actors, especially before 2017. Burundi’s pre-crisis civic space was influenced by the civil society mobilisation during the Arusha Peace Process.[5] Initially, participation in the Arusha Peace Process was limited to the warring parties and political parties. Civil society, religious, women and youth groups’ participation was originally limited to sporadic consultations and informal channels. However, they leveraged collaborative action and protest to influence the process. For example, the outcomes from the All-Party Burundi Women’s Peace Conference, a parallel platform for women representatives of political parties and armed groups, were included in the Arusha Agreement.[6] Nilsson et al. argue that while the Arusha Peace Process has often been cited as a case study of inclusive mediation, civil society participation was largely confined to the elite level.[7]

Burundi’s civic space consolidated in the first decade after the Arusha Agreement, becoming more influential in the country’s political dynamics despite the government’s intimidation attempts.[8] By 2015, Burundi’s civic space was characterised by a variety of influential non-state groups, including civil society organisations, Imbonerakure militia, the influential Ubushingantahe (traditional community leaders), and a wide range of political parties. Burundi’s civil society landscape had been reinforced by establishing networks with local, regional and international actors. Civil society networks strengthened the citizen diplomacy track by enhancing the capacity and promoting the participation of women and youth in preventive diplomacy initiatives. For example, the coalition among the Pan-African Lawyers Union (PALU), East African Civil Society Organisations’ Forum and three other societies jointly petitioned the East African Legislative Assembly to intervene in Burundi. This reflects Popplewell’s argument that Burundi’s historical hybridity has internationalised civil society, which facilitated the development of links while credibly representing local non-state interests.[9]

However, Burundi’s government implemented a crackdown against civil society as the crisis escalated. The government’s crackdown included the inclusion of ethnic quotas, restrictions on international financial flows and the banning of organisations. As the situation deteriorated, international observers and civil society organisations implicated the country’s security in illegal detention, torture and extra-judicial killings of journalists, opposition supporters and civil society activists. Civil society members, including Jean Bigirimana, Charlotte Umugwaneza and Marie-Claudette Kwizera, were killed or remain missing.[10] Moreover, the CNDD-FDD facilitated youth militia, Imbonerakure, were implicated in the implementation of a systematic campaign of violence against opposition members.[11]

This created a hostile environment, which resulted in citizens being reluctant to engage with regional actors due to fear of reprisals. The government crackdown significantly affected the implementation of the Inter-Burundi Dialogue by shifting the composition of Burundi’s non-state actor landscape. Many prominent opposition leaders, civil society actors and journalists went into exile.[12] Benjamin Mkapa’s facilitation team attempted to address this by sending delegates to meet with civil society actors in exile. Moreover, the United Nations Secretary-General (UNSG) report indicates that the Catholic Church did not send representatives to attend the fourth round of the Inter-Burundi Dialogue.[13] Roman Catholics constitute over 62% of Burundi’s Christian population, making its absence in preventive diplomacy efforts significant.

The government’s crackdown also impeded the recruitment of local non-state actors across the country to participate in the Inter-Burundi Dialogue. The EAC’s recruitment challenges were reinforced by the absence of established regional frameworks for engagement with non-state actors. This resulted in ineffective recruitment processes that excluded several grassroots actors because the main EAC dialogues did not have an application process for interested parties to opt in. Moreover, Benjamin Mkapa acquiesced with the government’s request to exclude some opposition actors and civil society from the proceedings.[14] Consequently, the representativeness and credibility of each subsequent round of the Inter-Burundi Dialogue were negatively affected.

The Burundi government’s refusal to cooperate

The Burundian government’s ongoing refusal to cooperate with the EAC represents the second main pitfall of regionalising national dialogues. The government’s hostility towards regional interventions extended beyond the Inter-Burundi Dialogue. This intransigence ranged from refusing to adopt resolutions and not fully participating in the Inter-Burundi dialogues to withdrawing from the International Criminal Court (ICC),[15] launching parallel dialogue processes,[16] and refusing human rights investigators access to relevant sites.[17] This created significant challenges for the full implementation of measures such as the deployment of the African Prevention and Protection Mission in Burundi (MAPROBU) and the work of the AU and Human Rights Council’s fact-finding missions. The most notable impact of the government’s refusal to cooperate was the reversal of MAPROBU and the delay in deploying human rights observers.[18]

The government’s agreement to participate in the Inter-Burundi Dialogue while simultaneously undermining the dialogue further illustrates this point. The facilitator’s team faced serious resistance from the government, which included refusing to engage with opposition actors, attempting to merge regional and national dialogues, and boycotting the fourth and fifth rounds of the Inter-Burundi dialogue. Benjamin Mkapa eventually resorted to shuttle diplomacy during the Inter-Burundi Dialogue because the government refused to meet with the opposition directly.

The government also co-opted pro-regime civil society to legitimise its actions, which represents an extension of the government’s refusal to cooperate with the Inter-Burundi Dialogue meaningfully. The UNSG’s report noted one instance of this:

Civil society organisations allied to the Government boycotted the meeting, however, despite having received airplane tickets issued by the United Nations, noting that the facilitator had failed to respond positively to the Government’s preconditions.[19]

The government’s decision to launch a rival national dialogue platform through the National Commission for Inter-Burundian Dialogue (CNDI) to act as an alternative to the regional dialogue presented the EAC’s main obstacle.[20] The CNDI began conducting national dialogues and consultative sessions on the political crisis in 2016. Both Pierre Nkurunziza and the Minister of the Interior reinforced the centrality of the CNDI in finding political solutions for the crisis. Burundi’s government also attempted to force the EAC to shift the location of the Benjamin Mkapa-led facilitation to Burundi.[21]

In a further dent to the regional dialogues, in November 2017, the government adopted the CNDI’s recommendations on the proposed constitutional amendments.[22] Burundi’s government co-opted sympathetic civil society to give this process legitimacy. However, continental and regional actors refused to accept this claim, particularly due to concerns about inclusivity and credibility.[23] Additionally, the EAC resisted the government’s attempts to merge the national and regional dialogues. However, eventually, under international pressure, the government resumed participation in the EAC Facilitation after these legitimation efforts failed. The government’s cooperation proved ineffectual as it rejected Benjamin Mkapa’s final Facilitator’s Report and roadmap, which had been submitted to the EAC Summit in February 2019.[24] The rejection of Benjamin Mkapa’s report stalled the EAC’s efforts, reinforcing the idea of the ineffectiveness of regional-led national dialogues.

Lack of effective coercive diplomacy

The EAC’s Inter-Burundi Dialogue failure to navigate the Burundi government’s civil society crackdown and refusal to cooperate was largely due to the AU and EAC’s reluctance to deploy coercive diplomacy measures.[25] The Inter-Burundi Dialogue presented the EAC with a potentially ground-breaking opportunity to regionalise national dialogues to prevent the escalation of a political crisis. The EAC’s approach reflects how the continental normative framework hinders continental and regional actors from harnessing coercive diplomacy in favour of diplomatic measures. This preference is driven by the need to balance sovereignty, non-coercion and non-indifference.[26] According to Muggah and White, preventive diplomacy is conducted from the perspective of policy-makers and practitioners’ cultural and regional preferences.[27] The preferred preventive diplomacy approach of the AU, RECs and Regional Mechanisms (REC/RMs) relies on diplomacy and mediation.

The EAC hence dismissed the prospects of applying any economic sanctions despite lobbying by civil society organisations once preventive diplomacy was streamlined under the Inter-Burundi Dialogue.[28] Unfortunately, the EAC’s lack of coercive diplomacy measures weakened the Inter-Burundi Dialogue because Burundi’s government had no incentive to cooperate fully in these initiatives. This was because the lack of coercive measures means there are no consequences for authoritarian states restricting or co-opting civil society while regional interventions are underway.

The EAC’s refusal to use coercive measures could have been offset by strategic coordination with the AU, which could have allowed Benjamin Mkapa to leverage the continental body to extract conditionalities from the belligerents. However, two key issues prevented this strategy: firstly, the AU lacked the political will to effectively deploy coercive tools, such as deploying a regional force and withdrawing Burundian forces from participating in continental peace support operations. The AU Peace and Security Council (PSC) failed to address reports from the fact-finding missions on Burundi’s shift to clandestine tactics against non-state actors.[29] This reinforces Wasinski’s argument that multi-level governance mechanisms have an ambivalent impact on the rule of law in Africa.[30] According to Leclercq, this is because states like Burundi use mock compliance, such as allowing a fact-finding mission to be deployed while continuing the crackdown through clandestine means.[31] Moreover, the PSC’s failed attempts to deploy the MAPROBU effectively weakened its leverage on Burundi.[32]

Secondly, the Inter-Burundi Dialogue was not linked to the AU’s other conflict prevention efforts. Failing to link the Inter-Burundi Dialogue to the AU’s human rights observer missions was a notable disconnect between multi-track and preventive diplomacy initiatives in Burundi. The AU’s threat of sanctions issued at the 551st meeting in October 2015 was not contingent on the Burundi government’s cooperation with the Inter-Burundi Dialogue.[33] The International Crisis Group notes that institutional rivalry played a role in the EAC’s refusal to align the Inter-Burundi Dialogue with the AU.[34] This indicates the weaknesses in how the implementation of the principle of subsidiarity and, subsequently, the ineffective division of labour between the AU and the RECs impedes the ability of regional actors to conduct national dialogues successfully.

Conclusion

The Inter-Burundi Dialogue had the potential to set a precedent for regionalising national dialogues to navigate political and constitutional crises in member states. While the Inter-Burundi Dialogue had limited impact, it created dialogue platforms for civil society actors and other non-state actors. These efforts helped build consensus and provide information to participants in the citizen diplomacy tracks. Regional officials noted that they prioritised the youth and women representatives. Moreover, the EAC officials attempted to circumvent the government’s crackdown on the opposition and civil society by using shuttle diplomacy to interact with exiled actors. Rupesinghe, as well as Göldner-Ebenthal and Dudou, point to this as a critical objective of this approach because it promotes inclusivity in peace processes.[35] The impact of these dialogue processes was reinforced by international civil society organisations that facilitated engagement between the regional structures and grassroots levels.

Despite the Inter-Burundi Dialogue’s modest achievement, this article concludes that regional actors cannot effectively conduct national dialogues because, firstly, the restrictions on non-state actors by governments have a significant impact on the outcomes of the processes. These restrictions are motivated by the blurred boundaries between civil society and opposition political parties. Such crackdowns on civil society impede the recruitment processes of local non-state actors to participate in multi-track diplomacy. This is more so in the absence of established regional frameworks for engagement with non-state actors. Secondly, regional actors are largely unable to extract cooperation from intransigent governments without coercive instruments. This challenge is compounded by the tendency of authoritarian governments to co-opt pro-government civil society and launch rival national dialogue platforms to legitimise internal processes such as constitutional amendments. This article concludes that the effectiveness of regional-led national dialogues to prevent impending political and electoral violence in authoritarian contexts is limited. Additionally, the coordination challenges at the strategic level between the AU and RECs in implementing the principle of subsidiarity to allow regional actors to leverage the AU’s political authority contribute to these limitations.

The article, therefore, recommends that RECs create formal channels to engage with civil society actors. This would allow RECs to maintain a register of civil society actors independent from governments. Additionally, this would increase REC’s access to local infrastructures for peace and ensure inclusivity of multi-track diplomacy initiatives.

References

[1] Göldner-Ebenthal, Karin and Dudoue, Veronique (2017) From Power Mediation to Dialogue Support? Assessing the European Union’s Capabilities for Multi-Track Diplomacy, Berlin: Berghof Foundation.

[2] UNHCR (2018) ‘Burundi risks becoming a forgotten refugee crisis without support’, Available at: https://www.unhcr.org/news/briefing/2018/2/5a79676a4/burundi-risks-becoming-forgotten-refugee-crisis-support.html [Date accessed: 10 April 2025].

[3] EAC (2015) ‘Communiqué: 3rd Emergency Summit of Heads of State of the East African Community on the situation in Burundi’, Available at: https://reliefweb.int/report/burundi/communiqu-3rd-emergency-summit-heads-state-east-african-community-situation-burundi [Date accessed: 10 April 2025]

[4] Mutangadura, Chido (2022) ‘The Management of Electoral Violence Through Preventive Diplomacy: Lessons Learned from Burundi’, Nelson Mandela University, Awarded 25 April 2025, [unpublished]

[5] Muyango, Astère (2011) ‘Opportunities for setting up a TRC in Burundi’, IJR Policy Brief Number 3, Available at: https://africaportal.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/IJR_Policy_Brief_No_3_December_2011_Astere_Muyango_English_summary_txt.pdf [Date accessed: 24 June 2025].

[6] Linekar, Jane (2018) ‘Women in Peace and Transition Processes’, Inclusive Peace & Transition Initiative. Available at: https://www.inclusivepeace.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/case-study-women-burundi-1996-2014-en.pdf [Date accessed: 24 June 2025].

[7] Nilsson, Desirre; Svensson, Issak; Teixeira, Barbara; Lorenzo, Luis-Martinez; and Ruus, Anton (2020) ‘In the streets and at the table: Civil society coordination during peace negotiations’, International Negotiation, 25(2), 225–251.

[8] International Crisis Group (2011) ‘Burundi: From Electoral Boycott to Political Impasse’, Africa Report No. 169, Available at: https://www.crisisgroup.org/africa/central-africa/burundi/burundi-electoral-boycott-political-impasse [Date accessed: 14 April 2025].

[9] Popplewell, Rowan (2019) ‘Civil Society, Hybridity and Peacebuilding in Burundi: Questioning Authenticity’, Third World Quarterly, 40(1), 129–146.

[10] International Federation of Action by Christians for the Abolition of Torture (2016) ‘Civil society alternative report to the Committee Against Torture on Burundi’, Available at: https://www.fiacat.org/images/pdf/Alternative_report_from_civil_society_CAT_58_Burundi.pdf [Date accessed: 24 June 2025].

[11] Matfess, Hilary (2018) ‘Impunity, the Imbonerakure, and Instability in Burundi’, Armed Conflict Location & Event Data (ACLED) Available at: https://acleddata.com/2018/10/25/impunity-the-imbonerakure-and-instability-in-burundi/ [Date accessed: 24 June 2025].

[12] Human Rights Watch (2021) ‘April 2015 – June 2020: A Chronology of Repression of Media and Civil Society in Burundi’, Available at: https://www.hrw.org/news/2021/05/26/april-2015-june-2020-chronology-repression-media-and-civil-society-burundi [Date accessed: 24 June 2025].

[13] UNSG (2018) ‘Report of the Secretary-General on the Situation in Burundi’, S/2018/89, Available at: https://undocs.org/S/2018/89 [Date accessed: 6 April 2025].

[14] Butty, James (2016) ‘Civil Groups Angered by Exclusion from Burundi Peace Talks’, Voice of Africa, Available at: https://www.voanews.com/a/civil-groups-demand-explanation-for-exclusion-from-burundi-talks/3341786.html [Date accessed: 24 June 2025].

[15] Coalition for the International Criminal Court (2017) ‘Victims lose out as Burundi leaves ICC’, Available at: https://www.coalitionfortheicc.org/latest/resources/burundi-and-icc [Date accessed: 24 June 2025].

[16] International Refugee Rights Initiative (2018) “We Need to Talk” Dialogue and Peace Agreements in Burundi’, Available at: http://refugee-rights.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/IRRI-Burundi-report-final-ENG-July-2018.pdf [Date accessed: 24 June 2025].

[17] Amani Africa, (2021) ‘Discussion on the AU Human Rights Observers and Military Experts to the Republic of Burundi’, Available at: https://amaniafrica-et.org/discussion-on-the-au-human-rights-observers-and-military-experts-to-the-republic-of-burundi/ [Date accessed: 24 June 2025].

[18] Dersso, Solomon (2016) ‘To Intervene or Not to Intervene? An inside view of the AU’s decision-making on Article 4(h) and Burundi’, The World Peace Foundation, Available at: https://worldpeacefoundation.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/AU-Decision-Making-on-Burundi_Dersso.pdf [Date accessed: 24 June 2025].

[19] UNSG (2018) ‘Report of the Secretary-General on the situation in Burundi’, S/2018/1028, Available at: https://undocs.org/en/S/2018/1028 [Date accessed: 7 April 2025], p. 4.

[20] Ibid, International Refugee Rights Initiative (2018)

[21] Manishatse, Lorraine (2017) ‘Burundi 2020: Is President Nkurunziza already at it again?’ African Arguments, Available at:

https://africanarguments.org/2017/08/burundi-2020-is-president-nkurunziza-already-at-it-again/ [Date accessed: 24 June 2025].

[22] Africa Center for Strategic Studies (2017) ‘Dismantling the Arusha Accords as the Burundi Crisis Rages On’, Available at: https://africacenter.org/spotlight/dismantling-the-arusha-accords-as-the-burundi-crisis-rages-on [Date accessed: 15 April 2025].

[23] UNSG (2017) ‘Report of the Secretary-General on Burundi’, S/2017/165, Available at: https://undocs.org/S/2017/165 [Date accessed: 5 April 2025].

[24] The Citizen (2016) Mkapa rejected in Burundi, Saturday, December 10, 2016 — updated on April 20, 2021, Available at: https://www.thecitizen.co.tz/tanzania/news/national/mkapa-rejected-in-burundi-2575366 [Date accessed: 24 June 2025].

[25] Wilén, Nina and Williams, Paul (2018) The African Union and coercive diplomacy: The case of Burundi, Egmont Institute, Available at: https://www.egmontinstitute.be/app/uploads/2018/12/Accepted-Manuscript-AU-and-Coercive-Diplomacy-the-Case-of-Burundi.pdf [Date accessed: 24 June 2025].

[26] Desmidt, Sophie and Hauck, Volker (2017) ‘Conflict management under the African Peace and security architecture (APSA)’, European Centre for Development Policy Management, Available at: https://ecdpm.org/work/conflict-management-under-the-african-peace-and-security-architecture-apsa [Date accessed: 15 April 2025].

[27] Muggah, Robert and White, Natasha (2013) ‘Is there a Preventive Action Renaissance? The Policy and Practice of Preventive Diplomacy and Conflict Prevention’, Norwegian Peacebuilding Resource Centre (NOREF) Report no. 28.

[28] Sabala, Kizito (2023) Challenges and Prospects for The East African Community in Mediation: The Case Of The Burundi Mediation, ACCORD, Available at: https://www.accord.org.za/wp-content/uploads/2024/06/Monograph-2023-Challenges-and-prospects.pdf [Date accessed: 24 June 2025].

[29] Ibid. Wilén, Nina and Williams, Paul (2018)

[30] Wasinski, Marek (2014) ‘Endemic Disregard for the International Rule of Law in Africa’, Polish Review of International and European Law, 3 (3–4), 7–34.

[31] Leclercq, Sidney (2018) ‘Between the Letter and the Spirit: International Statebuilding Subversion Tactics in Burundi, Journal of Intervention and Statebuilding, 12(2), 159–184.

[32] Bedzigui, Yann and Alusala, Nelson (2016) ‘The AU and the ICGLR in Burundi’, Central Africa Report, Available at: https://issafrica.s3.amazonaws.com/site/uploads/car9-1.pdf [Date accessed: 7 April 2025].

[33] African Union (2015) Communiqué of the 551st Meeting of the Peace and Security Council. Available at: https://www.peaceau.org/en/article/communique-of-the-551st-meeting-of-the-peace-and-security-council [Date accessed: 25 June 2025].

[34] International Crisis Group (2016) ‘The African Union and the Burundi Crisis: Ambition versus Reality’, Crisis Group Africa Briefing No. 122, Available at: https://www.crisisgroup.org/africa/central-africa/burundi/african-union-and-burundi-crisis-ambition-versus-reality [Date accessed: 14 April 2025].

[35] Rupesinghe, Kumar (1997) The General Principles of Multi-Track Diplomacy, Durban: ACCORD; Göldner-Ebenthal and Dudoue (2017) From Power Mediation to Dialogue Support? op. cit.