The United Nations Security Council (UNSC) remains one of the most powerful organs of global governance, tasked with maintaining international peace and security. However, its structure and decision-making processes have long been criticised for being outdated and unrepresentative, particularly in their exclusion of African countries from permanent membership. Despite Africa comprising 54 states – the largest regional bloc in the UN – and contributing significantly to UN peacekeeping operations, it remains without a permanent seat on the Council. This discrepancy raises fundamental questions about equity, legitimacy, and the effectiveness of the multilateral system in addressing the security concerns of an increasingly multipolar world. Calls for reform have grown stronger in recent years, driven by Africa’s rising political and economic influence and the continent’s persistent demand for a more inclusive global order.

The push for Security Council reform is not a new phenomenon. The debate has been ongoing for years, with various proposals put forward to expand the Council’s composition and distribute power more equitably. African states, through the African Union (AU), have articulated their collective position in the Ezulwini Consensus, which calls for two permanent seats with veto power and additional non-permanent seats for Africa. This demand is rooted in the historical marginalisation of African voices in global decision-making and the disproportionate impact of UNSC resolutions on the continent1. However, the path to reform remains fraught with challenges, as permanent members with veto power continue to resist structural changes that could dilute their influence.

At the heart of this issue lies the broader struggle for a more representative and effective multilateral system. While the continent has demonstrated its capacity to contribute meaningfully to international security, the absence of permanent African representation in the Security Council limits its ability to shape key decisions. The lack of African voices in high-level deliberations perpetuates a system where policies and interventions are often designed without sufficient input from those most affected by them.

This article examines the structural imbalance of the UNSC, the diplomatic strategies pursued by African states and the AU to push for reforms, and the geopolitical and institutional obstacles that hinder progress. By assessing Africa’s quest for permanent representation and veto power, the study seeks to shed light on the implications of these reforms for global governance, multilateral diplomacy, and the future of Africa’s engagement with the international system. Ultimately, understanding the dynamics of Security Council reform is essential for evaluating the prospects of a more equitable and responsive global security architecture.

The UNSC, through Resolution 1973, authorised military intervention under the principle of the Responsibility

to Protect, which led to the NATO – led airstrikes and the eventual overthrow of Muammar Gaddafi. Photo: United

States government work.

Structural imbalance and representation deficit

The structural imbalance and representation deficit in the UNSC is one of the most glaring examples of Africa’s marginalisation in global governance. Established in 1945, the UNSC has remained largely unchanged despite the vast shifts in international relations, including the decolonisation of Africa, the emergence of new global powers, and the increasing relevance of regional organisations. Africa, which consists of 54 member states and accounts for a significant portion of the UN’s agenda – particularly in peacekeeping and conflict resolution – remains excluded from permanent representation, creating a governance system that does not adequately reflect contemporary global power dynamics.

The exclusion of Africa from permanent membership in the UNSC has serious implications for the legitimacy and effectiveness of the Council’s decisions, particularly those directly impacting African states. A striking example is the Council’s role in authorising interventions and sanctions in Libya, despite the A3 (the three non-permanent African members of the UNSC) abstaining from the vote. The case of Libya in 2011 illustrates this imbalance. The UNSC, through Resolution 1973, authorised military intervention under the principle of the Responsibility to Protect (R2P), which led to the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation (NATO)-led airstrikes and the eventual overthrow of Muammar Gaddafi. While the intervention was framed as a humanitarian measure, it resulted in state collapse, prolonged instability, and the proliferation of armed groups across the Sahel region. The AU had proposed a diplomatic resolution to the crisis, advocating for a ceasefire and negotiations, but its recommendations were largely ignored by the UNSC’s permanent members. The sidelining of Africa’s regional perspective in such high-stakes decisions underscores the problematic nature of a Security Council that enforces policies without direct African input.

Africa is the largest contributor of troops to UN peacekeeping missions, with countries such as Ethiopia, Rwanda, and Ghana consistently providing significant personnel to operations in conflict zones. Photo: UN/Eskinder Debebe.

Another example of the consequences of Africa’s lack of permanent representation can be seen in the handling of peacekeeping operations. Africa is the largest contributor of troops to UN peacekeeping missions, with countries such as Ethiopia, Rwanda, and Ghana consistently providing significant personnel to operations in conflict zones. Yet, these nations have no substantive say in the strategic decisions governing these missions. The deployment of peacekeeping missions in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (MONUSCO) and South Sudan (UNMISS) has frequently been criticised for lacking a clear, locally informed mandate that aligns with the needs of affected communities. The structural imbalance means that decisions about funding, rules of engagement, and withdrawal timelines are dictated by non-African powers that may not fully grasp the complexities on the ground. The resulting inefficiencies and discontent among host nations further highlight why Africa’s exclusion from permanent membership is not just a symbolic issue but one that has tangible consequences for security and governance on the continent.

Additionally, the representation deficit extends to the power of the veto, a privilege exclusively held by the five permanent members, namely, China, France, Russia, the United Kingdom (UK), and the United States of America (USA). The veto has historically been used to advance the strategic interests of these powers, often at the expense of crisis resolution in Africa. For instance, Russia and China have repeatedly vetoed resolutions aimed at addressing human rights abuses and conflict in Sudan and Syria, primarily due to their political and economic interests in these countries2. At the same time, Western powers such as the USA, the UK, and France have been selective in their interventions, sometimes prioritising economic and geopolitical gains over genuine peace efforts3. Without a permanent African presence in the Council, the continent is left vulnerable to decisions shaped by external interests rather than regional priorities and perspectives4.

The demand for structural reforms, particularly under the framework of the Ezulwini Consensus, reflects Africa’s longstanding call for a more equitable distribution of power within the UNSC. The consensus, adopted by the AU in 2005, advocates for two permanent African seats with veto power, arguing that reforms must not only expand membership but also address the entrenched power dynamics that continue to sideline African voices. However, resistance from the existing permanent members has stalled progress, as each veto-wielding power fears that reform could dilute their own influence5. The failure to implement meaningful reforms despite widespread acknowledgement of the Council’s outdated structure underscores the deep-seated challenges of global power politics and the persistence of post-colonial hierarchies in international institutions.

The structural imbalance and representation deficit within the UNSC perpetuates a system in which Africa remains a subject rather than an active decision-maker in matters that affect its security and political future. This exclusion not only weakens the legitimacy of the Council’s decisions but also undermines the principles of democracy and fairness in global governance. Without meaningful reform, the UNSC risks becoming increasingly disconnected from contemporary geopolitical realities, reinforcing perceptions that it serves the interests of a few powerful states rather than the broader international community.

The AU’s reform proposals and diplomatic strategies

The AU has consistently advocated for a reformed and more equitable UNSC that reflects the realities of the 21st century. At the heart of Africa’s demands is the Ezulwini Consensus, which calls for two permanent seats with veto power and additional non-permanent seats for Africa. This proposal is rooted in the principle of equitable geographic representation and the recognition that Africa, as a major player in global peace and security affairs, deserves a meaningful voice in the Council’s decision-making processes. The AU argues that the current structure of the UNSC is an extension of a post-World War II order that no longer aligns with contemporary global power dynamics6. Despite widespread international support for reforms, Africa’s proposals have faced persistent obstacles, largely due to resistance from the existing permanent members and the complexity of global diplomatic negotiations.

The Ezulwini Consensus has been a cornerstone of Africa’s diplomatic strategy, yet its effectiveness has been limited by the lack of a unified African front and the realities of power politics at the UN. While the consensus reflects a collective African demand, individual African states have sometimes pursued separate diplomatic engagements that undermine a cohesive strategy. For instance, countries such as Nigeria, South Africa, and Egypt – often seen as contenders for potential permanent seats – have at times engaged in bilateral negotiations with external powers, raising concerns about whether Africa can present a truly unified front in the reform debate. This internal fragmentation has weakened the AU’s negotiating power, as permanent members of the UNSC have exploited divisions among African states to delay or dilute reform proposals7.

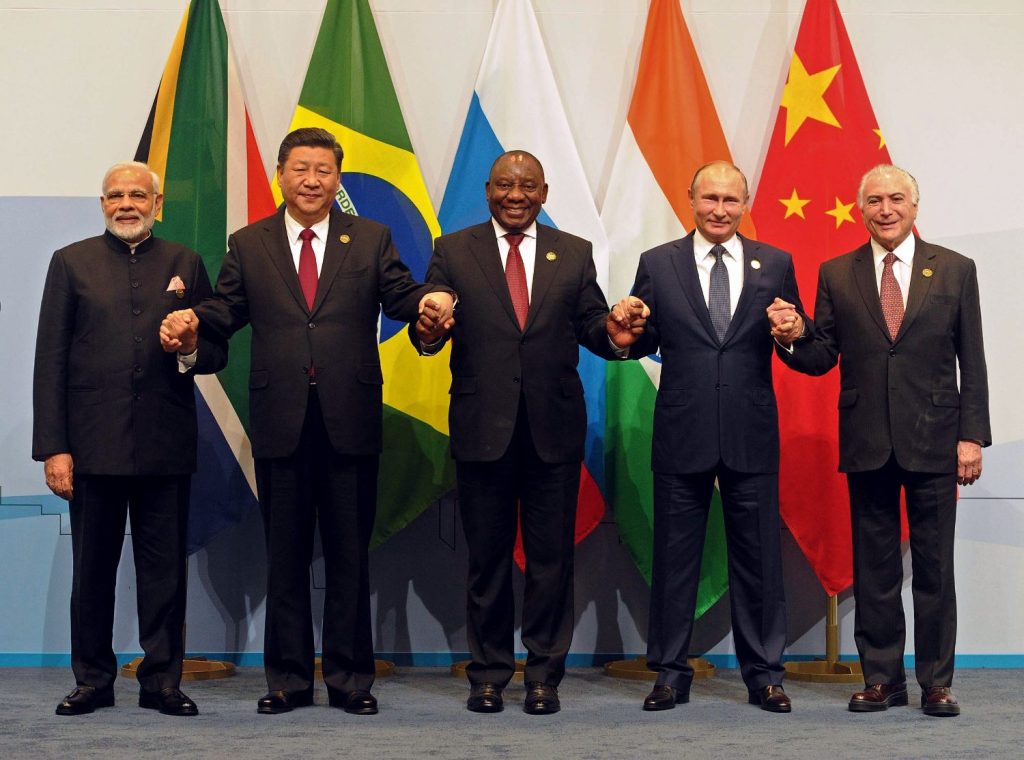

The AU has sought the support of other regional blocs, such as the G77 and BRICS, to amplify its demands. Photo: GCIS.

Diplomatically, the AU has engaged in various high-level negotiations and alliances to push for its reform agenda8. African leaders have consistently raised the issue at the UN General Assembly, and the AU has sought the support of other regional blocs, such as the G77 and BRICS (Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa), to amplify its demands. In recent years, Africa has received backing from influential voices, including France, which has expressed support for an African permanent seat, though without specifying whether it should include veto power. However, such endorsements have often been symbolic, and have not translated into concrete commitments at the Security Council level. The USA, China, and Russia have remained ambivalent or outright resistant to any reforms that would alter the balance of power within the Council, particularly concerning the veto system. This diplomatic deadlock illustrates the challenge of achieving meaningful change within an institution that is inherently structured to protect the interests of its most powerful members.

An example of the AU’s reform advocacy can be seen in the UN’s 75th-anniversary discussions in 2020, where African leaders reiterated their demands for a more inclusive Security Council. South Africa, during its tenure as a non-permanent member of the UNSC (2019–2020), used its position to highlight Africa’s marginalisation and push for structural changes. However, its efforts largely remained within the realm of diplomatic rhetoric rather than leading to substantive policy shifts. Similarly, Kenya, which held a non-permanent seat from 2021 to 2022, sought to emphasise African security concerns, but its influence remained limited by the overarching dominance of the permanent members. These cases highlight the paradox that while African states participate in the Council’s deliberations, they lack the institutional power to shape long-term policies in ways that serve African interests.

The AU has also explored alternative diplomatic strategies, including leveraging Africa’s economic partnerships and regional security contributions as bargaining tools in reform discussions9. The increasing role of African-led peacekeeping operations, such as the AU Transition Mission in Somalia (ATMIS) and the G5 Sahel Joint Force, underscores Africa’s growing responsibility in maintaining global security. African nations have argued that if they are expected to bear the burden of conflict resolution on the continent, they should also have a permanent say in the Council’s decisions regarding those conflicts. However, despite Africa’s strategic importance in global security, the existing power structure within the UN has largely kept the continent in a subordinate position, limiting the effectiveness of these diplomatic approaches.

The failure of African reform proposals to gain traction reflects a broader challenge within the multilateral system: the difficulty of achieving institutional change in the absence of strong political will from dominant global powers10. The UNSC, as currently structured, operates on a model that prioritises the interests of a few over the collective needs of the international community. While the AU’s diplomatic efforts have kept the reform agenda alive, they have yet to produce tangible changes in the Council’s composition. Without stronger coordination among African states, strategic alliances with reform-minded nations, and sustained diplomatic pressure, Africa’s aspirations for permanent representation and veto power risk remaining an unfulfilled ambition rather than a concrete reality.

The AU’s reform proposals and diplomatic strategies reflect both the urgency and the difficulty of restructuring a global governance system deeply rooted in historical power imbalances11. While Africa’s case for reform is compelling, the political realities of the UN system mean that meaningful change will require not only diplomatic persistence but also a fundamental shift in the way global powers perceive Africa’s role in international decision-making. Until then, Africa remains a crucial, yet underrepresented actor in the world’s most powerful security institution.

Geopolitical and institutional barriers to reform

The reform of the UNSC has been a longstanding issue in global governance, yet it remains one of the most politically complex and institutionally rigid processes due to entrenched geopolitical interests and systemic barriers12. The existing permanent members hold a disproportionate amount of power, particularly through their veto, which allows them to unilaterally block any substantive changes to the Council’s structure. This institutional design, established in the immediate aftermath of World War II, was meant to ensure stability by concentrating decision-making in the hands of the major powers at the time. However, as global power dynamics have evolved, the resistance of these states to any meaningful reform has become a significant obstacle to Africa’s pursuit of permanent representation. The geopolitical calculations of these states, shaped by their national security, economic, and strategic interests, have led to a pattern of selective support or outright obstruction, making the prospect of reform exceedingly difficult.

One of the primary geopolitical barriers to reform lies in the differing positions of the P5 members regarding Council expansion. While France and the United Kingdom have expressed conditional support for Africa’s inclusion in a reformed UNSC, their backing has often stopped short of advocating for veto power, which is a key component of the Ezulwini Consensus. The USA, while periodically engaging in discussions about reform, has been reluctant to push for changes that could diminish its own influence. China and Russia, for their part, have strategically used their positions to maintain the status quo, as any dilution of the existing power structure could challenge their ability to assert influence. This division among the permanent members has resulted in a deadlock that prevents any meaningful restructuring of the Council.

The case of India’s bid for permanent membership highlights the broader resistance to reform and its implications for Africa. India, like Africa, has consistently pushed for greater representation in the UNSC, particularly through its involvement in the G4 alliance alongside Brazil, Germany, and Japan. However, despite its growing economic and geopolitical influence, India has faced opposition from China, which sees a more powerful India as a threat to its regional dominance. This pattern of geopolitical rivalry is similarly reflected in Africa’s case, where some P5 members fear that a stronger African presence could shift the balance of power within the UN in ways that are not necessarily aligned with their strategic interests. As a result, Africa’s demands for permanent representation have been met with diplomatic manoeuvring rather than concrete commitments, with P5 members often using procedural tactics to delay or deflect discussions on meaningful reform.

Beyond the resistance of the permanent members, institutional barriers within the UN system itself further complicate the reform process13. The amendment of the UN Charter, which governs the composition and functioning of the UNSC, requires not only a two-thirds majority in the General Assembly but also ratification by all five permanent members. This means that even if an overwhelming majority of UN member states support reform – a scenario that has been demonstrated in multiple General Assembly resolutions – the process can still be effectively blocked by a single permanent member. This institutional safeguard was designed to prevent unilateral changes to the post-war security architecture but has instead entrenched a system where power remains concentrated among a small group of states, making the reform process more symbolic than actionable.

The AU’s push for reform through the Ezulwini Consensus and the Sirte Declaration has also been hindered by intra-African divisions, which the existing power structures have often exploited. While the AU has maintained a broad consensus on the need for two permanent seats with veto power, there has been a lack of agreement on which African states should fill these positions. Countries such as Nigeria, South Africa, and Egypt have been seen as leading contenders, but regional rivalries and competing national interests have prevented Africa from presenting a unified, unequivocal demand14. This internal discord has given P5 members the ability to justify inaction by pointing to Africa’s lack of consensus, effectively weakening the continent’s negotiating position.

The institutional rigidity of the UNSC is further evident in its decision-making processes, where informal practices and diplomatic alignments play a critical role in shaping outcomes. The influence of major Western powers in African affairs, often exercised through strategic alliances, economic dependencies, and security partnerships, means that Africa’s diplomatic leverage within the UN is frequently constrained. The use of UNSC resolutions to authorise military interventions, impose sanctions, or establish peacekeeping mandates in Africa without permanent African representation illustrates the imbalance of power. The 2011 intervention in Libya is a key example, where the Security Council’s decision, heavily influenced by France, the UK, and the US, led to the destabilisation of Libya and broader insecurity in the Sahel region. African voices, including the AU’s proposed alternative peace plan, were largely ignored, demonstrating the consequences of Africa’s exclusion from the decision-making process.

The economic and strategic interests of powerful states also shape their reluctance to support reform. China, for instance, has expanded its economic footprint across Africa through large-scale infrastructure investments, debt diplomacy, and resource extraction. Maintaining the current UNSC structure allows China to exert influence over African states without having to contend with an empowered African bloc within the Council. Similarly, Western powers such as the USA and France have military bases and strategic partnerships across Africa, making them wary of any structural changes that could limit their ability to shape security policies in the region. These geopolitical calculations mean that while African states may receive rhetorical support for reform, the actual political commitment to changing the status quo remains weak.

The persistent geopolitical and institutional barriers to reform illustrate the fundamental challenge of transforming a system that was designed to be resistant to change. While Africa’s demand for permanent representation in the UNSC is based on legitimate claims of fairness, historical redress, and global equity, the entrenched interests of the existing powers make meaningful reform an uphill battle. Without a major shift in the balance of power or a concerted effort by a broad coalition of states to challenge the current structure, Africa’s aspirations for greater representation risk remaining unfulfilled, reinforcing the systemic inequalities that characterise global governance today.

Abraham Ename Minko is a Senior Researcher and Policy Analyst in peace, security, and conflict resolution. He holds a PhD in Political Science and International Relations. His research interests are UN Peace Operations, Terrorism and Counter Violent Extremism, Peace and Conflict Resolution, Mediation and Negotiation, International Humanitarian Law and Armed Conflicts, Peacekeeping, and Peacebuilding.

Endnotes

1 Aleksovski, S.; Bakreski, O.; and Avramovska, B. (2014) ‘Collective Security – The Role of International Organisations – Implications in International Security Order’, Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences, 5(27), 274–282.

2 Nádasi, T. (2021) The Possible Prospects of the Weak Veto reform proposal for the United Nations Security Council: A discourse analysis of United Nations Security Council meeting documents, Bachelor’s thesis, Malmö University, Available at: http://urn.kb.se/resolve?urn=urn:nbn:se:mau:diva-43220

3 Yilmaz, F. (2007) The United Nations Security Council Reform: A Critical Approach, Master’s thesis, Linköping University, Available at: http://urn.kb.se/resolve?urn=urn:nbn:se:liu:diva-9330

4 Rukambe, K. (2017) United Nations Security Council and the veto power of the permanent members, Master’s dissertation, University of Pretoria, Available at: http://hdl.handle.net/2263/65718

5 Chatterjee, D. K. (2011) ‘United Nations Security Council’, In: Encyclopedia of Global Justice, Available at: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4020-9160-5_1119.

6 De Volder, E. (2010) Regionalism under the United Nations Framework: Exploring the limits and possibilities for regional enforcement action under the UN Charter with a special focus on Chapter VIII UN Charter, Master’s dissertation, Tilburg University.

7 Mohammad, R. W. (2023) ‘United Nations Security Council Powers, Practice, and Effectiveness Of Security Council’, Indian Journal of Law and Legal Research, 5(1), 1–48, Available at: https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7606283

8 Brown, W. and Harman, S. (2013) ‘African Agency in International Politics: An Introduction’, In: Brown, W. and Harman, S. (Eds), African Agency in International Politics, London: Routledge (pp. 1–15).

9 Fafore, O. A. (2020) ‘The African Union’s Collective Security Mechanism and the Challenges of Armed Non-State Actors’, Journal of African Union Studies, 9(3), 87–105.

10 Oloruntoba, S. O.; and Falola, T. (2022) ‘Africa in the Changing Global Order: The Past, the Present, and the Future’, In: Oloruntoba, S. O.; and Falola, T. (Eds), The Palgrave Handbook of Africa and the Changing Global Order, Cham: Palgrave Macmillan (pp. 1–22), Available at: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-77481-3_1

11 Mlambo, V. H.; Enaifoghe, A. O.; Zubane, S.; and Mlambo, D. N. (2021) ‘Examining the Role of Africa in a Changing Global Order: Challenges and Opportunities’, African Journal of Public Affairs, 12(2), 27–42.

12 Maluwa, T. (2023) ‘Stalling a Norm’s Trajectory?: Revisiting U.N. Security Council visiting U.N. Security Council Resolution 1973 on Libya and its Ramifications for the Principle of the Responsibility to Protect’, California Western International Law Journal, 53(1), 69–46.

13 Weiss, T. G.; Forsythe, D. P.; Coate, R. A.; and Pease, K. K. (2014) The United Nations and the Changing World Politics, Boulder, CO: Westview Press.

14 Tieku, T. K. (2019) ‘The African Union: Successes and Failures’, Oxford Research Encyclopaedia of Politics, 1–25.