- Policy & Practice Brief

The institutionalisation of mediation support within the ECOWAS Commission

Executive Summary

The Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) Commission established the Mediation Facilitation Division (MFD) in June 2015 to backstop mediation efforts undertaken by its mediation organs, member states, non-state actors and joint initiatives with other international organisations, such as the African Union Commission (AUC) and the United Nations (UN). In January 2016, the structure was further upgraded to a directorate within the Department of Political Affairs, Peace and Security (PAPS). This Policy & Practice Brief (PPB) examines the rationale for taking the bold step to institutionalise a mediation support structure within the ECOWAS Commission; the legal and normative instruments that underpin its mediation interventions; the mandate, vision and scope of operation of the mediation support structure; and the key activities undertaken by the structure within one year of its existence. The PPB identifies the uniqueness of ECOWAS’s experiences in interventions in the 1990s, and the subsequent importance accorded to preventive diplomacy and mediation as a key factor that informed the decision to establish a mediation support structure – in contrast to using an ad hoc arrangement to backstop its mediation efforts in the past. This new arrangement, the PPB argues, will ensure that mistakes such as the marginalisation of ECOWAS in mediation processes in the region, the disconnect between the ECOWAS Commission and its appointed mediators, facilitators and special envoys, are remedied. It will also ensure a coordinated approach to capacity building and mediation knowledge management within the ECOWAS Commission and its institutions, as well as with its partners, including mainstreaming Tracks II and III mediation into official Track I mediation.

Introduction

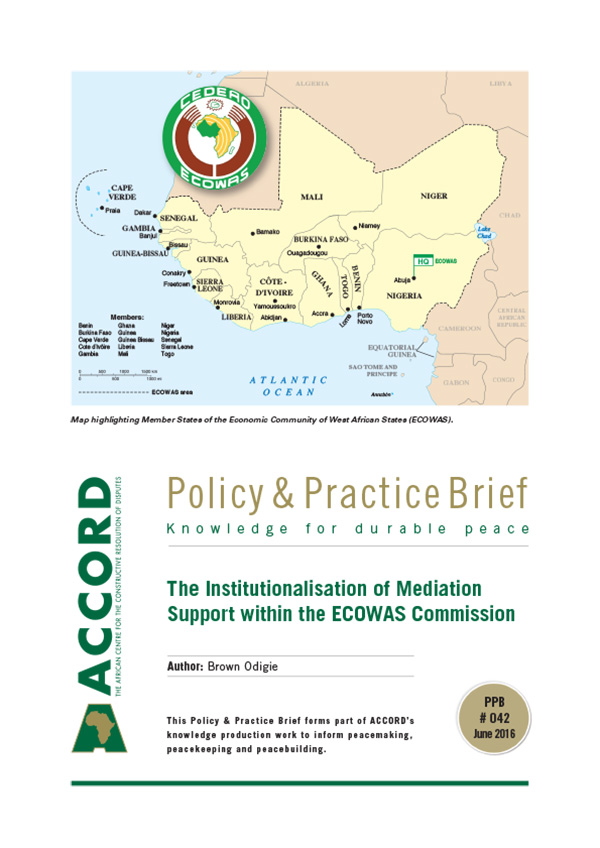

ECOWAS was established on 28 May 1975 through the Treaty of Lagos, as a regional economic group with the mandate of promoting economic integration among its member states. In 1993, the treaty that established ECOWAS was revised to accelerate the process of regional integration, as well as to address the debilitating effects on the integration agenda caused by civil conflicts in some member states at the time. Among others, the main objective of ECOWAS is to promote cooperation and integration. In its 2010 strategic document, ECOWAS established what it calls Vision 2020,1 in which it endeavours to move from an ECOWAS of states to an ECOWAS of people. is strategy entails the creation of a borderless region, leading to a single economic space in which its people transact business and live in dignity and peace under the rule of law and good governance.

Whilst regional integration was the driving force for the establishment of ECOWAS, political conflicts and instability in the 1990s became the wake-up call to focus its attention on developing a regional architecture for peace and security. This led to the development of the 1999 Protocol Relating to the Mechanism for Conflict Prevention, Management, Resolution, Peacekeeping and Security, the supplementary 2001 Protocol on Democracy and Good Governance and the 2008 ECOWAS Conflict Prevention Framework (ECPF). Component two of the ECPF focused the attention of ECOWAS on institutionalising and strengthening preventive diplomacy to “diffuse tensions and ensure the peaceful resolution of disputes within and between Member States by means of good offices, mediation, conciliation and facilitation based on dialogue, negotiation and arbitration”.2 How has ECOWAS fared in operationalising and institutionalising preventive diplomacy and mediation as a component of its peace and security architecture? What have been the existing gaps in its preventive diplomacy and mediation interventions, and what efforts have been initiated to bridge these gaps? What is the rationale for establishing a mediation support structure within the ECOWAS Commission? These are the questions this PPB addresses.

ECOWAS Mediation Organs and their Legal and Normative Basis

Though established in 1975, the first legal and normative instruments in which the concept of mediation as a tool for con ict prevention, resolution and management was first encapsulated was the Revised ECOWAS Treaty, signed in Cotonou, Benin, on 24 July 1993. Under the provisions of Article 58 of the said Treaty, member states of ECOWAS are urged to “undertake to work to safeguard and consolidate relations conducive to the maintenance of peace, stability and security within the region”.3

To this end, member states shall “co-operate with the community in establishing and strengthening appropriate mechanisms for the timely prevention and resolution of intra-state and inter-state conflicts”, paying particular attention to the need to “employ where appropriate, good offices, conciliation, mediation and other methods of peaceful settlement of disputes”. From these initial provisions on the need for member states to cooperate with the community in resolving intra-state and inter-state conflicts through the use of mediation and other preventive diplomacy tools, ECOWAS proceeded to develop a more comprehensive normative instrument for conflict prevention, management, resolution, peacekeeping and security, commonly referred to as the “1999 Mechanism”.

Among other objectives, this mechanism aims to “implement the relevant provisions of Article 58 of the Revised Treaty” and “promote close cooperation between ECOWAS Member States in the areas of preventive diplomacy and peace-keeping”.4

The institutions established by the mechanism for the purpose of preventive diplomacy and mediation include the Authority of Heads of State and Government, the Mediation and Security Council (MSC) and the Executive Secretariat – which has now been transformed to the ECOWAS Commission – headed by the president of the Commission. The mechanism equally established the Council of Elders – now the Council of the Wise (CoW) – as a supporting organ of the institutions of the mechanism for the purpose of preventive diplomacy and mediation. By its design, the CoW is a council of eminent personalities, assembled by the president of the ECOWAS Commission and who, on behalf of ECOWAS, are to use their good offices and experience to play the role of mediators, conciliators and facilitators.5 Another structure for mediation, by virtue of the functions and responsibilities assigned to it by the mechanism, is that of the special representatives of the president of the ECOWAS Commission in member states.6 In addition to these are special envoys and facilitators who are most often, former heads of state and government or sitting presidents and prime ministers. All these institutions and organs are expected to be backstopped by a support team from the ECOWAS Commission in carrying out their mandate.

ECOWAS has a rich history of preventive diplomacy and mediation in the region, especially with the coordinated efforts in responding to the civil war that broke out in Liberia, Sierra Leone, Guinea, Guinea Bissau and CoÌ‚te d’Ivoire in the 1990s. Some of these preventive diplomacy and mediation efforts were singularly undertaken by ECOWAS, whilst others were through joint initiatives with other international entities such as the AUC and UN, backstopped by ECOWAS staff on an ad-hoc basis.7 The formal establishment of a mediation support structure–the MFD, with the aim to backstop the mediation efforts of ECOWAS and other joint mediation initiatives only came to fruition in June 2015.

The Rationale and Roadmap for the Establishment of the ECOWAS MFD

The idea of a mediation facilitation structure within ECOWAS can be said to have taken root in the uniqueness of ECOWAS’s experiences in interventions in the 1990s, and the subsequent importance accorded to preventive diplomacy and mediation as an effective response to the numerous intra-state conflicts that had engulfed many member states since the early 2000s. This was leveraged by the lessons learnt and After Action Review (AAR) exercise undertaken by the Directorate of Political Affairs (DPA) of the ECOWAS Commission, which started in the late 2000s with the holding of the International Conference on Two Decades of Peace Processes in West Africa: Achievements, Failures and Lessons, in Monrovia, Liberia, in 2010.

The main objective of the Liberia Conference was to review ECOWAS’s peacemaking efforts by evaluating the interventions carried out from 1990 to 2010, with a view to learning lessons and building on its achievements. Whilst conference participants acknowledged the peacemaking efforts of ECOWAS, they identified a weak preventive diplomacy structure as a major challenge and subsequently called on ECOWAS “to strengthen its mediation efforts by setting up the Mediation Facilitation Division in the Political Affairs Directorate… to facilitate preventive diplomacy activities by the Commission”.8

The Malian crisis of 2012 – partly triggered by the fall of the Muammar Gaddafi regime in Libya and the subsequent chain reaction, which almost led to the total collapse of the political, military and security institutions of the State of Mali – further brought to the fore the weak preventive diplomacy structure of ECOWAS. These two experiences inspired the urgent need for ECOWAS to establish a mediation support structure within the ECOWAS Commission. The 43rd Ordinary Session of the Authority of ECOWAS Heads of State and Government, which took place in Abuja on 16–17 July 2013, “instructed the Commission to expedite a review of the ECOWAS Peace and Security Architecture with regard to preventive diplomacy and rapid military response capability, against the background of the lessons learned in Mali.”9 Pursuant to this directive, the ECOWAS Commission initiated the Mali AAR from November 2013 to February 2014. The report of the AAR indicated that “aspects of extant ECOWAS Community Instruments were compromised by some processes and agreements entered into in Mali due to the absence of resourced mediation support facility at the ECOWAS Commission, as well as the weak link between the ECOWAS Mediators and the Commission”.10 The report noted “the marginalisation of the ECOWAS Commission in the mediation process, leading to inconsistencies with ECOWAS normative frameworks and hitches in the implementation of the 6 April 2012 Framework Agreement between the ECOWAS Mediator and the CNRDRE”.11 To bridge this gap, it was recommended that “all ECOWAS-mandated Mediation or Facilitation teams should work closely with the ECOWAS Commission, the latter being responsible for facilitating and backstopping the work of Mediators and Facilitators. To this end, the Commission was requested to expedite the establishment of the MFD without further delay.”12

These important recommendations were immediately acted upon by the ECOWAS DPA, which had commenced the conception of a mediation support structure for ECOWAS as early as 2007/2008. In the aftermath of the Liberian Conference and well before the Malian crisis of 2012, Dr Abdel-Fatau Musah, former director of the ECOWAS DPA, and his staff had developed the concept note. They also held both formal and informal consultations within ECOWAS and with experts, with a view to establishing a mediation support structure within ECOWAS. These efforts eventually culminated in the holding of a Needs Assessment Workshop from 30 October to 1 November 2012 in Lagos, Nigeria, for the establishment of the MFD. This was done with the support and participation of the UN, the Centre for Humanitarian Dialogue (HD Centre) and the Danish International Development Agency (DANIDA).

In giving insight into the rationale for the establishment of the MFD, Musah noted that “despite the positive results achieved through the peacemaking interventions of ECOWAS, a lot more could have been achieved and many mistakes avoided, if a mediation support structure had existed at the Commission to facilitate, back-stop and guide these efforts”.13 He further remarked that “coordination and synergy between the mediation efforts undertaken by national and local actors on the one hand, and regional mediation processes on the other, needed to be enhanced, if ECOWAS was to give real meaning to its vision of transforming the region “from an ECOWAS of States into an ECOWAS of Peoples”.14 One can therefore conclude that the MFD was conceived as an institutional structure that “sought to address these identified challenges and gaps in ECOWAS preventive diplomacy and mediation interventions, drawing its legitimacy from the Preventive Diplomacy component of the ECPF, as well as the ‘2010 Monrovia Declaration’ adopted at the ECOWAS International Conference”15 and important lessons captured from the 2014 Mali AAR.

From these experiences and processes, the ECOWAS Commission consequently established the mediation facilitation structure as a division within the DPA, with the recruitment in 2015 of four staff, namely, head of the division, programme officers; for capacity building, operations and the mediation resource centre. In January 2016, the division was upgraded to a directorate.

The Mandate, Vision and Scope of Operation of the MFD

The Needs Assessment report for the establishing of the MFD identified the mandate of the directorate as “support, coordination, and monitoring of mediation efforts by ECOWAS Institutions and Organs, by Member States and non-State actors, and by joint initiatives”.16 Drawing from Article 49(h) of the ECPF, the report stated the vision of the MFD as “a mediation facilitation capacity within the ECOWAS Commission to promote preventive diplomacy in the region through competence and skills enhancement of mediators, information sharing and logistical support”.17

Furthermore, the report specified the broad scope of operation of the MFD to include, first, operational support, which entails the backstopping of mediation and shuttle diplomacy activities, the provision of guidance, background information, and analysis, monitoring and evaluation, as well as the facilitation of the mainstreaming of Track III mediation efforts into the ECOWAS mediation architecture. The second is the establishing of a mediation resource centre, which entails the creation and management of a library of mediation resources as well as the creation and management of a database of resource persons and issues in mediation. The third is capacity building in mediation, which entails facilitating the development of modules for mediation training; the organising of workshops, seminars and conferences for mediation resources; and facilitating exchange programmes for mediation resources.18

A close examination of the mandate, vision and scope of operation of the MFD as enumerated above reveals the intention and “willpower” of ECOWAS to transit from an ad hoc mediation support “regime” to building an institutional mediation support structure. This is a bold step, considering that ECOWAS is one of the few regional economic commissions (RECs) of the AUC that has established a mediation support structure.

The ECOWAS MFD in One Year: an Overview

One year might be too short a period to examine how the MFD has fared in pursuing its mandate, vision and objectives. True as this is for any newly established structure, there are some positive interventions to account for its establishment. Within the scope of its operation, the first being the backstopping of mediation efforts in the region, the MFD has been active in bridging the gaps between the ECOWAS Commission and its appointed mediators, facilitators and special envoys. It has backstopped the deployment of high-level consultative missions undertaken by the ECOWAS Commission to some member states in preparation for elections. This was the case for Guinea in 2015, and Niger between November 2015 and February 2016. Such efforts facilitated the creation of an enabling environment for the resolution of pre-electoral/political disputes prior to holding elections. It has also been providing technical support to ECOWAS’s special envoy to Guinea Bissau, H.E. Olusegun Obasanjo, towards the resolution of the political and institutional crises that the country has been experiencing since August 2015.

With respect to the second scope of operation – that is, mediation resource development – in August 2015 the MFD held a workshop to brainstorm and chart a roadmap for the development of an ECOWAS mediation roster, mediation guidelines and standard operating procedures (SOPs). In the framework of partnership and collaboration, and as part of the efforts to develop a mediation knowledge management (MKM) system for ECOWAS, in March 2016 it held a joint MKM seminar in Abuja, Nigeria, with the UN Office in West Africa and the Sahel (UNOWAS) and staff members from the UN Department of Political Affairs (UNDPA) Mediation Support Unit and the Guidance and Learning Unit of the Policy Mediation Division (PMD).

Within the third scope – capacity building, the MFD has so far held two training courses on negotiation and mediation as an instrument for conflict resolution for senior staff of the ECOWAS Commission, special and permanent representatives of the president of the ECOWAS Commission, members of the CoW, staff from some member states’ ministries of foreign affairs, and a representative of the West African Network for Peacebuilding (WANEP). These courses, facilitated by the Netherlands Institute of International Relations, Clingendael, and held in November 2015 and April 2016, focused on strengthening the negotiation and mediation skills of the participants, as well as the institutional capacity of the MFD. In December 2015 the MFD also partnered with the Legon Centre for International Affairs and Diplomacy (LECIAD) in Ghana, in holding a training course on mediation support processes for operational and mid-career staff from the ECOWAS Commission’s DPA, offices of the special and permanent representatives of the ECOWAS president in member states and staff from member states’ ministries of foreign affairs. This mediation training, undertaken by the MFD within one year of its establishment, might not be appreciated until what had been done in the past is looked at retrospectively. Whilst ECOWAS was very active in mediation prior to the establishing of the MFD, it never really had the strategic objective of mediation training. Nathan, in his article titled Mediation in African Conflicts: The Gap between Mandate and Capacity,19 notes that “whereas substantial time, effort and money are devoted to military trainings in order to ensure success, manage risk and prevent failure, little if any attention is paid to training African mediators” – and one would add mediation support staff. Nathan’s observation is quite true with respect to ECOWAS. For example, from 2006 up until the establishing of the MFD in 2015, the only training on mediation for ECOWAS actors involved in mediation and the support of mediation processes was the training organised by LECIAD in 2008. Only a few staff from PAPS had the opportunity of attending training on mediation, most often, self-sponsored.

Furthermore, in the same space of one year, personnel of the MFD between 31 May and 2 June 2016 undertook a working exchange visit to the AUC’s Preventive Diplomacy and Mediation structures to share experiences on mediation and deepen collaboration in joint mediation initiatives between the ECOWAS Commission and the AUC. This was important in order to avoid the tendencies of duplicating mediation efforts and/or avoiding incidences of multiplicity of mediation interventions and actors in a given ECOWAS member state where mediation is required, a common practice among international organizations, which is often uncoordinated and characterized by competitiveness.

The above is only a summary account of key activities undertaken thus far by the MFD, with much more in its priority workplan for 2016–2017. However, it must be noted that the MFD was able to embark on these activities largely because of the financial support and enormous goodwill from development partners – notably DANIDA and the Dutch Ministry of Foreign Affairs through its training facility on negotiation and mediation, and with technical support from UNOWAS and United Nations Mediation Support Unit (UNMSU).

Conclusion

The institutionalisation of a mediation support structure within the ECOWAS Commission did not simply emerge from the blue. It results from a well thought-out, rigorous and consultative process, with tremendous goodwill and support from numerous partners and stakeholders. In executing its mandate, the MFD should therefore leverage on such goodwill and, in particular, establish linkages and collaboration with similar structures within the AUC and the UN and other mediation resource centres, including deepening its collaboration with civil society organisations to mainstream Track III mediation into official Track I mediation. The ECOWAS management must ensure to prioritise the MFD in its budgetary appropriation. The MFD must also ensure it mobilises financial and technical resources from outside the ECOWAS to support its critical interventions.

With the coming on board of a mediation support structure – in contrast to the ad hoc arrangement of past mediation support – it could be expected that the mistakes of the past will not recur. This is not to say that there will not be new challenges in the mediation processes that will be undertaken by ECOWAS, but the fact that there is a dedicated structure to follow up on such challenges is a positive development which must be commended.

Endnotes

- ECOWAS Commission. 2010. ECOWAS Vision 2020: Towards a Democratic and Prosperous Community. ECOWAS Commission, Abuja.

- ECOWAS Conflict Prevention Framework regulation MSC/REG.1/01/08,. P. 24.

- The Revised Treaty of ECOWAS. 1993. ECOWAS Commission, Abuja.

- 1999 Mechanism Article 3 (b and g.)

- Article 20 of the 1999 Protocol states that the Executive Secretary (now President of the ECOWAS Commission) shall compile annually, a list of eminent personalities to be comprised of persons from various segments of society, including women, political, traditional and religious leaders. The list shall be approved by the Mediation and Security Council at the level of the Heads of State and Government. From the list, the President of the Commission can assemble eminent personalities to constitute the Council of the Wise (CoW), who will normally be requested to deal with a given conflict situation and report back to the President of the Commission. From an active membership of 13 in 2007/2008 to only two active members in 2016, the CoW as a mediation organ of ECOWAS has almost become comatose. Following the establishment of the MFD in June 2015, there is a renewed impetus to reposition the CoW as an effective mediation organ of ECOWAS. Also see Afolabi, B.T. 2009. Peacemaking in the ECOWAS Region: Challenges and Prospects. Conflict Trends, Issue 2.

- Currently, there are five member states of ECOWAS where there are Special Representatives, namely, Liberia, Guinea Bissau, Guinea, CoÌ‚te d’Ivoire and Mali. It must also be stated here that in 2014, by Decision A/DEC.9/03/2014, the ECOWAS Heads of State and Government in its 44th Ordinary Session adopted a decision creating the Offices of Permanent Representatives in all Member States. Presently Burkina Faso and Togo have Permanent Representatives. The mandate of the Permanent Representatives is somewhat broader than that of the Special Representatives, in that, while the Special Representatives are appointed to oversee political and peacebuilding interventions in post-conflict countries, Permanent Representatives are to promote the visibility of ECOWAS in Member States and work with the various national stakeholders and ECOWAS institutions and agencies for the purposes of promoting national ownership and implementation of ECOWAS regional agendas. The Mediation Facilitation Directorate has viewed Permanent Representatives as having a preventive diplomacy and mediation role in the given member state of their assignment.

- ECOWAS has been involved in numerous preventive diplomacy and mediation interventions in the region, such as in the Liberian Peace Process, where former Nigerian Head of State, General (rtd.) Abdulsalami Abubakar, was appointed as ECOWAS Special Envoy/Mediator in 2002, resulting in the signing of the Accra Comprehensive Peace Agreement of 2003; again, in 2009, he was appointed as ECOWAS mediator in the Niger peace process, following an attempt by President Tandja to unconstitutionally extend his stay in power. Former president Olusegun Obasanjo of Nigeria was equally appointed as Special Envoy of ECOWAS to mediate in the post-election violence in CoÌ‚te d’Ivoire in 2010. Former president Blaise Compaore of Burkina Faso was ECOWAS Facilitator/Mediator in Togo (2005–2010), CoÌ‚te d’Ivoire (2007), Guinea (2008) and Mali (2012).

- Report of the ECOWAS International Conference in Two Decades of Peace Processes in West Africa: Achievements – Failures – Lessons, Monrovia, Liberia on 22–26 March. ECOWAS Commission, Abuja, May 2010.

- Report of the 43rd Ordinary Session of the Authority of ECOWAS Heads of State and Government. July 2013. ECOWAS Commission, Abuja.

- Ibid. p. 22.

- Ibid. p. 20.

- Ibid. p. 35.

- Report of the Needs Assessment Workshop for the Establishment of the ECOWAS Mediation Facilitation Division, Lagos, Federal Republic of Nigeria, 30 October – 1 November, 2012, p. 6.

- Ibid. p. 6.

- Ibid. p. 6.

- Ibid. p. 7.

- The Needs Assessment Report, p. 6 ad p. 25, the ECPF, Regulation MSC/REC.1/01/08.

- The Needs Assessment Report , p. 7.

- Laurie Nathan. 2007. Mediation in African Conflicts: The Gap between Mandate and Capacity. Africa Mediators’ Retreat.