- Policy & Practice Brief

Reflections on Success

By interweaving an analysis of the achievements with reflections from Women, Peace and Security (WPS) giants, this Policy and Practice Brief (PPB) seeks to flip the narrative around by focusing on the achievements in advancing and promoting women’s participation in peace processes, and highlighting all the reasons to celebrate the advances in the WPS agenda.

Executive Summary

This past year, the unprecedented novel coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic laid bare the shortcomings of our efforts to secure socioeconomic, gender and racial equality across the globe. As governments implemented measures to curb the spread of the virus, the most vulnerable of our communities were forced to carry a disproportionate burden of the pandemic. 2020 proved to be a year of difficult and frank conversations about the continued gaps and failings of our efforts to secure a more peaceful world. As we enter a new decade, still dealing with the COVID-19 pandemic and unsure of what the coming years will bring for gender equality generally and women’s participation in peace processes specifically, it is nonetheless important to take a moment to attest to what has been achieved. Indeed, a closer inspection of the last decade reveals that there is reason for celebration. In this regard, by interweaving an analysis of the achievements with reflections from Women, Peace and Security (WPS) giants, this Policy and Practice Brief (PPB) seeks to flip the narrative around by focusing on the achievements in advancing and promoting women’s participation in peace processes, and highlighting all the reasons to celebrate the advances in the WPS agenda.

Introduction

2020 was going to be a monumental year for the WPS Agenda and its adherents, as it marked the 20thanniversary of the adoption of United Nations Security Council Resolution 1325 (UNSCR 1325) and the 25thanniversary of the Beijing Declaration and Platform for Action. Commemorated at a time when the global community was faced with an unprecedented health pandemic which not only took the lives of three million[1]people but had also laid bare the extreme inequities that persist across the world, it was hard not to focus on the failures, gaps, challenges and continued barriers. In the middle of the celebrations, it was difficult not to be fearful for what the future holds, as we saw a global setback on the gender equality gains made.

Soon after governments implemented measures to curb the spread of COVID-19, we saw the most vulnerable of our communities disproportionally affected, of which the majority were women and girls. Consequently, 2020 became a year of frank and difficult conversations about the failings of efforts to achieve gender, racial and economic equality and human rights. The differentiated impact of the pandemic on women and girls is not a new phenomenon as they are often confronted with difficult and life-threatening situations arising from conflict, political instability, and challenges around access to basic rights. In 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic and especially the measures implemented to curb the spread presented rapidly changing situations with different pressures that disproportionately affected women’s social lives, daily routines, and means of generating income.

In spite of the challenges highlighted above, as we enter a new decade, it is crucial to take a moment to celebrate and speak to what has been achieved because there is, indeed, reason for celebration. Without this celebration, hope[2] is difficult to have because all we see is darkness. In this regard, this PPB seeks to flip the narrative around, focus on the achievements, and highlight all the reasons to celebrate the advances in the WPS agenda. In writing this, the hope is that all peacebuilders, practitioners, government allies, and policymakers can take a moment to applaud themselves and one another. The next decade will no doubt be a challenging one, and it will most likely require renewed commitment and energy to achieve the results we want to see.

The inspiration for this piece comes from 12 interviews the African Centre for the Constructive Resolution of Disputes (ACCORD), in partnership with the International Development Research Centre (IDRC), conducted with notable African women mediators. For the past two years, ACCORD has sat down with Mme Graça Machel, Marie Louise Baricako, Thelma Awori, Yasmin Jusu Sheriff, H.E. Netumbo Nandi-Ndaitwah, Helen Kezie-Nwoha, Ambassador Liberata Mulamula, Dr Brigalia Bam, Alice Nderitu, Leymah Gbowee, Betty Bigombe, and Aya Chebbi. We listened to their stories and insights and heard their thoughts on what the future holds for peace and security on the African continent, as well as the future of the WPS Agenda, more specifically.

Although there are many reasons to be critical of the slow progress made on the WPS agenda, as we have struggled with its meaningful implementation and achieving gender representation, it is also equally important to highlight what actually has been achieved because, as activist Rebecca Solnit said, ‘when you don’t know how much things have changed, you don’t see that they are changing or that they can change.’[3]Interweaving the achievements and the women’s reflections on these achievements, this PPB will highlight the successes over the past two decades.

Reasons to be hopeful: charting the success

I don’t think it’s been so dismal. I think we brought awareness to the problem, to the need for women to be at the table. And this has been with a lot of training of women as mediators. I think that we have mobilised a lot at the grassroots. There are lots of women grassroots peace groups. In Liberia, for instance, there are the peace huts. In Uganda, there are lots of women’s peace groups.[4]

Thelma Awori

It cannot be denied that over the last two decades and more, civil society organisations (CSOs), practitioners, policymakers, national governments, the African Union (AU), and several United Nations (UN) agencies have worked tirelessly to see the goals of the WPS agenda achieved. Looking at the numbers, however, it is clear that we have not gotten to where we want to be. To illustrate, according to statistics from the Council on Foreign Relations, ‘between 1992 and 2019, women constituted, on average, 13 per cent of negotiators, 6 per cent of mediators, and 6 per cent of signatories in major peace processes around the world.’[5] Moreover, the numbers show that women and girls continue to live in a state of insecurity. In 2018, for example, it was documented that ‘women and girls accounted for about 65 per cent of more than 45 000 detected trafficking victims globally.’[6]

The achievements, however, that can be celebrated include the mainstreaming of the agenda; the huge number of policy commitments; and the emergence of concrete actions to build the leadership capacities of women, including the emergence of women mediation networks.

Mainstreaming the agenda

Of course, there has been progress. That cannot be denied in terms of popularising the women, peace and security agenda.[7]

Ambassador Mulamula

One of the most significant accomplishments of the WPS agenda over the past two decades has been the ability to mainstream the agenda effectively at almost all levels, from the international to the local. Arguably, if the COVID-19 pandemic were to happen ten years ago, gender and the gendered implications of the pandemic would not have garnered the same attention as they did in 2020. As these gendered effects quickly revealed themselves, the UN, the AU, and CSOs around the world responded to the impact COVID-19 has had and will continue to have on women and girls. Responses have included important analyses to understand the gendered dimension of the pandemic fully, advocating for women’s representation in decision-making bodies related to the pandemic, and mobilising to support women at the grassroots level who have taken it upon themselves to help their communities during this time. There have also been efforts to provide space for dialogue on and sharing experiences of the COVID-19 pandemic and to ensure that women’s peacebuilding activities that continued during the pandemic are recognised and supported.

Leading the global responses to COVID-19, UN Secretary-General António Guterres made an appeal for a global ceasefire and an end to violence against women and girls (VAWG).[8] UN Women responded swiftly to the gendered impact of the pandemic. Examples of activities implemented by UN Women include the continued monitoring and rapid assessment of VAWG and COVID-19 in many countries, including Libya, Malawi, Morocco, South Africa and Egypt (see Infographic 1), and the UN Women’s #HeForSheAtHome campaign,[9] geared towards inspiring men and boys to help balance the burden of care in their households. UN Women South Africa, in partnership with Google and MTN, supported 4 500 women-owned businesses to access government stimulus funding by offering them virtual learning courses. UN Women Malawi supported awareness-raising and sensitisation of influencers, youth networks, and faith-based and traditional leaders on COVID-19, while addressing cultural practices that might impact the spread of the disease.[10]

The AU has shown strong leadership in being actively seized with the gendered impact of COVID-19. On 12 May 2020, in partnership with UN Women, the AU hosted the inaugural meeting of African Ministers for Gender and Women’s Affairs, under the theme ‘COVID-19 Response and Recovery – a Gendered Framework’.[11] In addition, on 28 May 2020, with the support of the AU, the African Women’s Leaders Network (AWLN) convened a virtual consultation on COVID-19 responses to provide a better understanding of the pandemic’s effect on women in Africa.[12] At the CSO level, in particular, organisations have been active in producing knowledge and useful analysis of the gendered impacts of the pandemic.[13]

Infographic 1: African Countries COVID-19 Response Measures and Gender Sensitivity[14]

Emergence of policies at the UN, AU, RECs, and National Governments

First, we have made progress. That the issue of women and peace has really become entrenched in the international agenda but also at the local and national level. That is why today, there are many countries that have set up national action plans on women and peace. The UN Women office is now fully engaged in advancing the implementation of Security Council Resolution 1325. Besides that, other related resolutions have been adopted almost every year by the Security Council.[15]

H.E. Netumbo Nandi-Ndaitwah

One of the significant reasons for the successful mainstreaming of the WPS agenda at the international, regional and national level, has been the wide array of policy commitments enacted. Although we are struggling to implement these commitments meaningfully and successfully, it is of significance that they, in fact, exist. For one, it demonstrates that these institutions remain committed to the agenda and its goals, but it also provides CSOs with tools to hold these institutions accountable to their commitments.

At the UN, since 2000, there have been nine additional resolutions on WPS, including 1820 (2009), 1888 (2009), 1889 (2010), 1960 (2011), 2106 (2013), 2122 (2013), 2242 (2015), 2467 (2019), and 2493 (2019), for a total of 10 resolutions speaking to the importance of the inclusion of women in peace processes.[16] Moreover, in 2013, the Convention for the Elimination of all Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW) Conference adopted Recommendation No. 30, which ensures that states now also have to report annually on WPS issues within this framework. It further ‘enlarges the applicability of the WPS Agenda to broader contexts (beyond conflict) and broadens the issues to include trafficking, refugees, HIV/AIDS, the arms trade and forced marriages.’[17] Lastly, in 2015, the UN adopted the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, which outlines 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) Member States have committed to addressing. Of particular importance to the WPS agenda are Goals 5 and 16, which address gender equality and call for more just, peaceful and inclusive societies.[18]

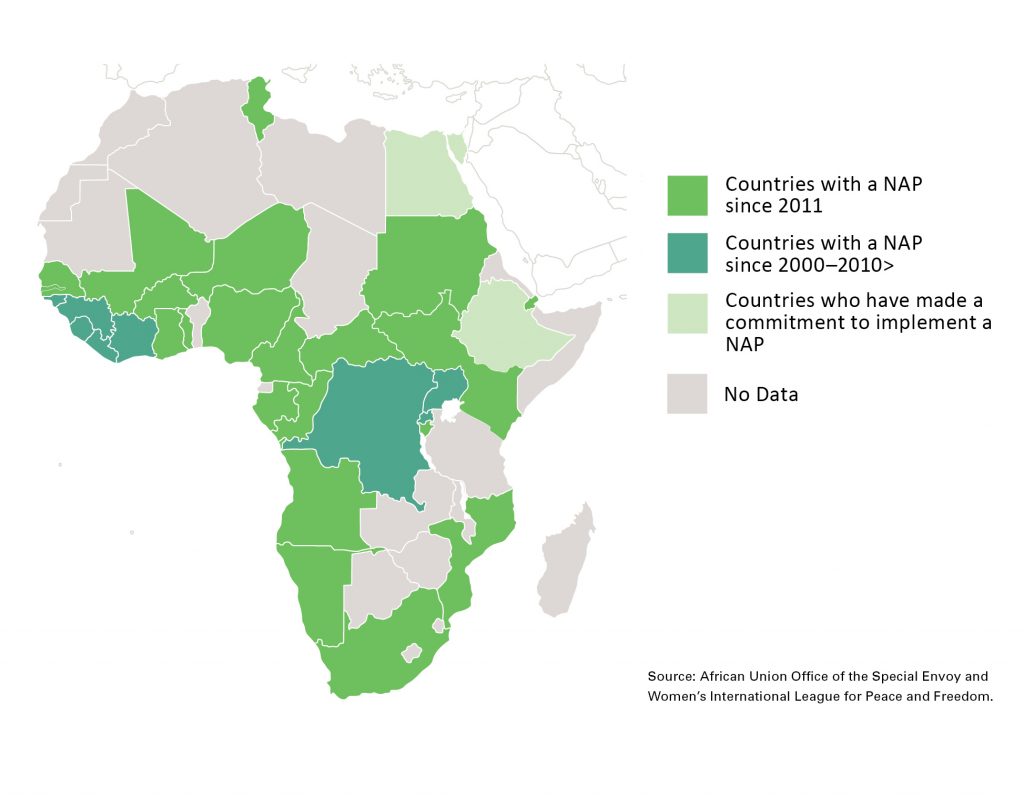

In Africa specifically, there is enormous activity and progress in relation to the WPS agenda. At the continental level, there is the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights on the Rights of Women, which is also known as the Maputo Protocol (2003), the Solemn Declaration on Gender Equality in Africa (2004), and Agenda 2063. We now have the AU Gender Policy (2009), the AU Strategy for Gender Equality and Women’s Empowerment (2018), the African Women’s Decade under the theme of Grassroots Approach to Gender Equality and Women’s Empowerment (GEWE) (2010-2020), and the AU Standard Operating Procedures for Mediation Support (2012). Moreover, the Office of the Special Envoy on Women Peace and Security at the AU, led by Mme Bineta Diop, developed the Continental Results Framework, which requires that Member States report on their implementation of the WPS Agenda.[19]

At the regional level, many of the Regional Economic Communities/Mechanisms (RECs/M) have shown dedicated efforts to the WPS agenda. For example, the Intergovernmental Authority on Development (IGAD) developed a Regional Action Plan (RAP) between 2011 and 2015 to act as a benchmark for Member States when creating their own national action plans (NAPs). The RAP supported the aims of tackling violence against women and girls, increasing the number of women at the negotiating table, and supporting gender-inclusive peace processes. Following IGAD’s lead, other RECs/M have also devised RAPs – including the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS), the East African Community (EAC), and most recently in 2018, the Southern African Development Community (SADC), making Africa the leader in regional approaches to WPS worldwide.[20] In addition, there is Article 28 of the SADC Protocol on Gender and Development, which calls for women’s ‘equal representation and participation in key decision-making positions in conflict resolution and peace building processes by 2015 in accordance with United Nations Security Council Resolution 1325 on Women, Peace and Security.’[21]

At the national level, 30 African countries have adopted NAPs, making Africa the continent with the highest per centage of NAPs.[22] Slovakia, Cyprus, Latvia, South Africa, Djibouti, Republic of Congo, Gabon, and Sudan are the latest countries to adopt NAPs in 2020 (see Infographic 2).

Infographic 2: African Countries with National Action Plans (2000-2020)[23]

Concrete actions to strengthen capacities of women mediators

I think we have gone a good way. It’s not that nothing has happened. Things have happened. For me, I think it’s already something very positive that we have that women’s mediators’ networks. It’s a very positive thing.[24]

Marie Louise Baricako

Lastly, there has been a dedicated effort across the continent to provide capacity building and training opportunities so women can gain and enhance the necessary skills to participate in peace processes, including mediation. Many of these efforts have been undertaken by civil society and, in some cases, national governments, and this has led to the creation of many international regional and national women mediator networks (WMNs) (see Table 1).

An example of a national government dedicated to the training of women mediators is South Africa through its Department of International Relations and Cooperation (DIRCO), which has been hosting the Gertrude Shope Annual Dialogue Forum (GSADF) since August 2015. Over the years, the GASDF has provided a platform for sharing experiences and best practices in peace and security initiatives by bringing together women from different countries. In 2019, it was announced that the Forum will also be creating the Gertrude Shope Peace and Mediation Network to provide a platform for South African and African women mediators to engage and advance the WPS Agenda, locally and internationally.[25]

Table 1: Examples of Women Mediator Networks (WMNs)

| Type | Name | About |

| International | The Network of African Women in Conflict Prevention and Mediation (FemWise-Africa) | Officially created in 2017, FemWise-Africa is the largest continental WMN to date, with a membership of over 400 women. The overall objective of the network is to strengthen the role of women in conflict prevention and mediation efforts in the context of the African Peace and Security Architecture (APSA).[26] |

| Regional | Mano River Women’s Peace Network (MARWOPNET) | MARWOPNET was established in 2000 in the West African region. It is known as one of the earliest WMNs established in Africa. Created in response to the violence in the Mano River Union, it brought together women from Guinea, Liberia and Sierra Leone to provide the women with a platform and avenue for participating in the peace processes in the region.[27] |

| National | INAMAHORO Movement, Women and Girls for Peace and Security | INAMAHORO Movement, Women and Girls for Peace and Security was established in 2015, after the political crisis in Burundi. Burundian women organised to address the root causes of the crisis and facilitate their peace advocacy in the country. The network continues to work to ensure Burundian women and girls are actively involved in the peace processes in the country.[28] |

Similarly, at the CSO level, there have been several initiatives to train women mediators across the continent. The Women’s International Peace Centre (Uganda) and ACCORD (South Africa) are two examples of African organisations leading the charge in training women.

From October to November 2020, for example, ACCORD, in collaboration with the AU’s Peace and Security Department (PSD) and Sida, hosted the 2020 FemWise-Africa Capacity Building Initiative. The blended virtual training programme focused on building the capacities of women at the Track III level, and provided introductory peacebuilding training and skills assessments, while also offering an opportunity to bring together various personalities from the Track I level during the Knowledge Sharing sessions. Over the course of eight weeks, the FemWise-Africa Capacity Building Initiative reached a total of 320 people from all across the world, including 184 FemWise-Africa members and 136 non-FemWise-Africa members (see Infographic 3).

Infographic 3: FemWise-Africa Capacity Building Initiative Participation

CONCLUSION AND RECOMMENDATIONS

I think that we should really take this Generation Equality message very, very seriously. We need the solidarity in order to push. I’m somebody who’s had twins, and other children, so I know what it means to deliver something. There’s that last push when the midwives are saying, “Push, push!” This is the time to push. We have to get this equality out and the relief that we have afterwards. We have to join ranks. We have to get every possible partner who can be with us. The men are very important in this. They have to open doors for us. We have to push.[29]

Thelma Awori

One resounding call from the women ACCORD interviewed that we must heed as we head into the next two decades is to implement all the policy commitments through meaningful action, if we want to see real change. As Dr Brigalia Bam puts it:

I think as we celebrate all these years of wonderful things within United Nations, within the African Union, we should also bear in mind that the time has come; that as women, we’re not going to fight for forever to prove that we are also capable human beings.[30]

In order to do so, Ms Helen Kezie-Nwoha suggests the following:

I think women of Africa, we need to put our hearts together. We can’t sit on resolutions. We can’t sit advocating forever. We now need to take action. My personal vision is that we create a movement of women who can go and stand between two warring parties in the field and say, “Stop now! We’re here physically. Here physically. Stop right now!” Look at Libya. Look at the women. Look at what is happening. Look at Sudan. Even South Sudan. We need to step out of our comfort zones. We need to stop the papers and become more realistic in terms of what we want to see change. We need to acknowledge that we need to change, but change needs to happen when we go out there now. So, for me moving forward, all these conversations is enough. Let’s just go and do it.[31]

Along similar lines, Mme Graça Machel suggests that we look at reviewing and rewriting UNSCR 1325. She shares:

Women have to begin a process of reviewing 1325. I am as bold as this. We need to review it so that we demand that any mediation, which is mandated by the UN or the African Union, it is mandatory that they have women as part of the mediation team. And also, that it is mandatory that those who are sitting at the table to negotiate peace, include women and young people. Otherwise, you refuse to participate. Because at the end of the day, as the situation is now, we give those who are non-state actors, who are now sitting at the table, much more legitimacy than women and young people and others who never went to war. Those who went to war, they have much more rights to write the terms in which peace is to take place than the victims, the millions of people in the country who have been victimised. If you want to put it in other words, give victims the voice and the space to shape the future.[32]

We may not be where we would have hoped to be 20 years on since the adoption of UNSCR 1325. Yet, we cannot deny that we have indeed come a long way. As we look to the future, it will be important to assess what is not working and what barriers remain in order to address them so that 20 years from now, we will have more reasons to celebrate.

The Author

Molly Hamilton is the Women, Peace and Security Programme Officer at ACCORD. Prior to joining ACCORD in 2019, she obtained her Bachelor of Arts Degree cum laude with a major in Political Science and minor in Women and Gender Studies from Mount Allison University, New Brunswick, Canada. Her areas of interests include women, peace and security and more specifically, countering sexual violence and gender-based violence.

Endnotes

[1] Number as of April 29, 2021. World Health Organization. 2021. WHO Coronavirus (COVID-19) Dashboard. Available from: <https://covid19.who.int/> [Accessed 30 April 2021].

[2] Author and activist Rebecca Solnit defines hope as the following, ‘It’s important to say what hope is not: it is not the belief that everything was, is, or will be fine. The evidence is all around us of tremendous suffering and tremendous destruction. The hope I’m interested in is about broad perspectives with specific possibilities, ones that invite or demand that we act. It’s also not a sunny everything-is-getting-better narrative, though it may be a counter to the everything-is-getting-worse narrative.’

[3] Solnit, R. 2016. Hope in the Dark: Untold Histories, Wild Possibilities. Chicago, USA, Haymarket Books. pp. xix.

[4] Interview with Thelma Awori. February 2020. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia.

[5] Council on Foreign Relations. 2020. ‘Women’s participation in peace processes.’ Available from: <https://www.cfr.org/womens-participation-in-peace-processes/> [Accessed 30 April 2021].

[6] UN Women. 2019. Facts and figures: Women, Peace, and Security. Available from: <https://www.unwomen.org/en/what-we-do/peace-and-security/facts-and-figures#_Peace> [Accessed 30 April 2021].

[7] Interview with Liberata Mulamula. August 2020. Durban, South Africa.

[8] Antonio Guterres. 2020. ‘Make the prevention and redress of violence against women a key part of national response plans for COVID-19.’ Available from: <https://www.un.org/en/un-coronavirus-communications-team/make-prevention-and-redress-violence-against-women-key-part> [Accessed 30 April 2021].

[9] HeForShe. 2020. ‘HeForShe launches global #HeForSheAtHome campaign.’ Available from: <https://www.heforshe.org/en/heforshe-launches-global-heforsheathome-campaign> [Accessed 30 April 2021].

[10] UN Women. 2020. UN Women Response to COVID-19 Crisis. Available from: <https://www.unwomen.org/en/news/in-focus/in-focus-gender-equality-in-covid-19-response/un-women-response-to-covid-19-crisis> [Accessed 30 April 2021].

[11] UN Women. 2020. ‘Meeting of African ministers in charge of Gender and Women’s Affairs on “COVID-19 response and recovery” – A gendered framework.’ Available from: <https://www.unwomen.org/en/news/stories/2020/5/announcer-african-ministers-in-charge-of-gender-and-women-on-covid-19-response-and-recovery> [Accessed 30 April 2021].

[12] Iknowpolitics. 2020. ‘African Women Leaders Network (AWLN) virtual consultation on COVID-19 responses.’ Available from: <https://www.iknowpolitics.org/en/news/events/african-women-leaders-network-awln-virtual-consultation-covid-19-responseses> [Accessed 30 April 2021].

[13] For example, ACCORD has producing its weekly COVID-19 Conflict and Resilience Monitor since March 2020. During the global crisis, ACCORD’s analysis has focused on the impact of the pandemic on conflict in Africa. Visit the Monitor here: https://accord.org.za/conflict-resilience-monitor/

[14] United Nations Development Programme. 2020. COVID-19 Global Gender Response Tracker. Available from: <https://data.undp.org/gendertracker/> [Accessed 30 April 2021].

[15] Interview with Netumbo Nandi-Ndaitwah. August 2020. Durban, South Africa.

[16] Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom. 2019. The Resolutions. Available from: <https://www.peacewomen.org/why-WPS/solutions/resolutions> [Accessed 28 October 2020].

[17] Republic of South Africa. 2020. National Action Plan on Women, Peace and Security – 2020 to 2025. Available from: <https://www.gov.za/sites/default/files/gcis_document/202103/south-african-national-action-plan-women-peace-and-security.pdf> [Accessed 30 April 2021].

[18] United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs. 2020. The 17 Goals. Available from: <https://sdgs.un.org/goals> [Accessed 30 April 2021].

[19] Republic of South Africa. 2020. National Action Plan on Women, Peace and Security – 2020 to 2025. Available from: <https://www.gov.za/sites/default/files/gcis_document/202103/south-african-national-action-plan-women-peace-and-security.pdf> [Accessed 30 April 2021].

[20] Poulsen, K. 2019. Implementation of the Women, Peace and Security Agenda in Africa. (Report no. 2018-6232). Available from: <https://um.dk/~/media/um/english-site/documents/danida/about-danida/danida%20transparency/documents/u%2037/2019/women%20peace%20and%20security%20agenda%20in%20africa.pdf?la=en> [Accessed 5 October 2020].

[21] South Africa Development Community. 2008. SADC Protocol on Gender and Development. Available from: <https://extranet.sadc.int/files/2112/9794/9109/SADC_PROTOCOL_ON_GENDER_AND_DEVELOPMENT.pdf> [Accessed 30 April 2021].

[22] According to data provided by the African Union’s Office of the Special Envoy on Women, Peace and Security.

[23] Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom. 2020. National-level implementation. <http://www.peacewomen.org/why-WPS/solutions/implementation> [Accessed 28 October 2020].

[24] Interview with Marie Louise Baricako. February 2020. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia.

[25] Republic of South Africa. 2020. National Action Plan on Women, Peace and Security – 2020 to 2025. Available from: <https://www.gov.za/sites/default/files/gcis_document/202103/south-african-national-action-plan-women-peace-and-security.pdf> [Accessed 30 April 2021].

[26] African Union. 2018. Strengthening African Women’s Participation in Conflict Prevention, Mediation Processes and Peace Stabilisation Efforts: Operationalisation of ‘FemWise-Africa.’” Available from: <https://www.peaceau.org/uploads/final-concept-note-femwise-sept-15-short-version-clean-4-flyer.pdf> [Accessed 30 April 2021].

[27] Makan-Lakha, P. and Yvette-Ngandu. 2017. The Power of the Collectives: FemWise-Africa. Durban, ACCORD. Available from: <https://accord.org.za/publication/the-power-of-collectives/> [Accessed 16 March 2021].

[28] INAMAHORO Movement, Women and Girls for Peace and Security. 2020. History. Available from: <https://en.barundikazi.org/a-propos> [Accessed 30 April 2021].

[29] Interview with Thelma Awori. February 2020. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia.

[30] Interview with Brigalia Bam. August 2019. Durban, South Africa.

[31] Interview with Helen Kezie-Nwoha. February 2020. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia.

[32] Interview with Graça Machel. March 2021. Durban, South Africa.