- Policy & Practice Brief

Women Mediation Networks

Twenty years since the adoption of the United Nations Security Council Resolution 1325 (UNSC 1325) on Women, Peace and Security (WPS), women remain underrepresented in peace processes. This underrepresentation has far-reaching consequences for the lives of many women and girls in post-conflict countries.

Executive Summary

Twenty years since the adoption of the United Nations Security Council Resolution 1325 (UNSC 1325) on Women, Peace and Security (WPS), women remain underrepresented in peace processes. This underrepresentation has far-reaching consequences for the lives of many women and girls in post-conflict countries. The low participation of women in peacemaking and formal peace negotiations calls into question the legitimacy of the process itself, and the evidence shows that the lack of women’s meaningful inclusion at the peace table leads to less representation during peacebuilding actions. To address this persistent exclusion and to ensure opportunities for societies to become more gender-equal are not lost, there has been a rapid emergence of regional and international Women Mediator Networks (WMNs). Comprised of a diverse group of women from various backgrounds and with different expertise and experience, these networks have the potential to be a transformative mechanism for achieving the goals outlined in the WPS Agenda. Analysing the emergence of WMNs and their potential to rejuvenate the implementation of the WPS project, this Policy and Practice Brief (PPB) seeks to answer the following questions: Why are more WMNs emerging? What impact will these networks have? Where do they fit into the existing global framework and how do they engage with this framework?

Introduction

Women’s critical roles in conflict resolution and peacebuilding are largely unrecognised and so too are the opportunities for cross-sharing and for understanding the root causes of conflict.

This informs the current paradigm driving the WPS Agenda and necessitates projects that gather and apply knowledge in creating solutions that ensure women count and move beyond merely counting women. From this perspective, WMNs are significant and provide institutionalised connections between the resources, knowledge and experience, and for sharing the best practices of its members who are working towards the objectives of the WPS Agenda.

This PPB reflects on the events of 2020 and what these mean for those working towards enhancing the WPS Agenda. The PPB has also incorporated research perspectives related to the following questions: Why are more WMNs emerging? What impact will these networks have? Where do they fit into the existing global framework, and how do they engage with this framework?

Why are more WMNs emerging?

The increase in WMNs is part of a response to the continued limitations on women’s participation in peace and security. This is largely linked to the disproportionate impact of the burdens associated with structural (relating to access) and material (relating to funding and capacity) barriers. Structural violence has been enforced at the nexus where traditional stereotypes of men and women in the home and society and institution building and law-making meet.[i] In conflict scenarios, this dynamic is exacerbated as women make up a small percentage of combatants, and they are often systematically targeted through acts of sexual and other forms of violence. Peace processes are also a symbolic and compelling representation of significant fundamental issues of (in)equality between men and women. Africa has come a long way in terms of gender equality and the protection of women’s rights at the policy level with the adoption of various legal instruments. Nevertheless, there are far fewer successes with regards to actioning these policies at all levels, especially during peace processes[ii] (see Table 1).

Historically, efforts to advance gender equality have been haphazard. These efforts target specific areas, or they are assigned to specific units intended to serve the entire system. So, these gender equalising efforts are not truly ‘mainstreamed’ in a meaningful, comprehensive, cross-sectoral, or coordinated way. Translating the WPS normative framework into valuable outputs requires access to more funding and greater influence and decision making power for girls and women during crisis and peacebuilding periods. To create this access, a ‘pipeline’ is required to build a reliable connection between international resources, regional and national institutions, and local women-focused civil society organisations (CSOs) at the forefront of building resilience against the outbreak and effects of conflicts and other emergencies.

Peace processes are also a symbolic and compelling representation of significant fundamental issues of (in)equality between men and women. Africa has come a long way in terms of gender equality and the protection of women’s rights at the policy level with the adoption of various legal instruments.

Due to the systematic and continual exclusion of women at the formal peace table, many women and girls have chosen the CSO route to have their voices heard and to participate before, during and after peace processes. These organisations range from informal groups or networks that mobilise around specific and emerging needs to formally established organisations with medium- or long-term goals and agendas. As a result, women-focused CSOs can play diverse roles spanning humanitarian resilience, preparedness, response, and recovery, and they can often adopt new responsibilities as needs change.

Table 1: Women’s participation in peace processes in Africa (1992–2011)[iii]

| WOMEN SIGNATORIES | WOMEN-LED MEDIATIONS | WOMEN WITNESSES | WOMEN IN THE NEGOTIATION TEAM | ||

| 1 | Sierra Leone (1999) | 0% | 0% | 20% | 0% |

| 2 | Burundi (2000) – Arusha | 0% | 0% | – | 2% |

| 3 | Somalia (2002) – Eldoret | 0% | 0% | – | 0% |

| 4 | Cote d’Ivoire (2003) | 0% | 0% | 0% | – |

| 5 | DRC (2003) | 5% | 0% | 0% | 12% |

| 6 | Liberia (2003) – Accra | 0% | 0% | 17% | – |

| 7 | Sudan (2005) – Naivasha | 0% | 0% | 9% | – |

| 8 | Darfur (2006) – Abuja | 0% | 0% | 7% | 8% |

| 9 | DRC (2008) – Goma –North Kivu | 5% | 20% | 0% | – |

| 10 | DRC (2008) – Goma –South Kivu | 0% | 20% | 0% | – |

| 11 | Uganda (2008) | 0% | 0% | 20% | 9% |

| 12 | Kenya (2008) – Nairobi | 0% | 33% | 0% | 25% |

| 13 | Central African Republic(2008) | 0% | 0% | 0% | – |

| 14 | Zimbabwe (2008) | 0% | 0% | 0% | – |

| 15 | Somalia (2008) | 0% | 0% | 0% | – |

| 16 | Central African Republic(2011) | 0% | 0% | 0% | – |

| Average | 0.6% | 4.6% | 4.6% | 3.5% |

Grassroots women-focused and women-led CSOs have been instrumental in the formation and subsequent proliferation of WMNs in Africa and around the world. In most cases, these networks have been formed out of a coalition of women-led CSOs. An early example is the Mano River Women’s Peace Network (MARWOPNET), created through Femmes Africa Solidarité’s[iv] (FAS) capacity-building and advocacy programming efforts in the West African region.[v] Established in 2000, MARWOPNET was one of the earliest WMNs established in Africa and created in response to the violence in the Mano River Union.[vi] It brought together women from Guinea, Liberia and Sierra Leone to provide them with a platform and avenue for participating in the peace processes in the region. Through the network, a delegation of Liberian women was present during the June 2003 Akosombo Talks,[vii] and in the words of President Ellen Johnson Sirleaf: “[o]nce unified, the women were instrumental in opening up dialogue among the leaders of their respective countries.”[viii]

Grassroots women-focused and women-led CSOs have been instrumental in the formation and subsequent proliferation of WMNs in Africa and around the world

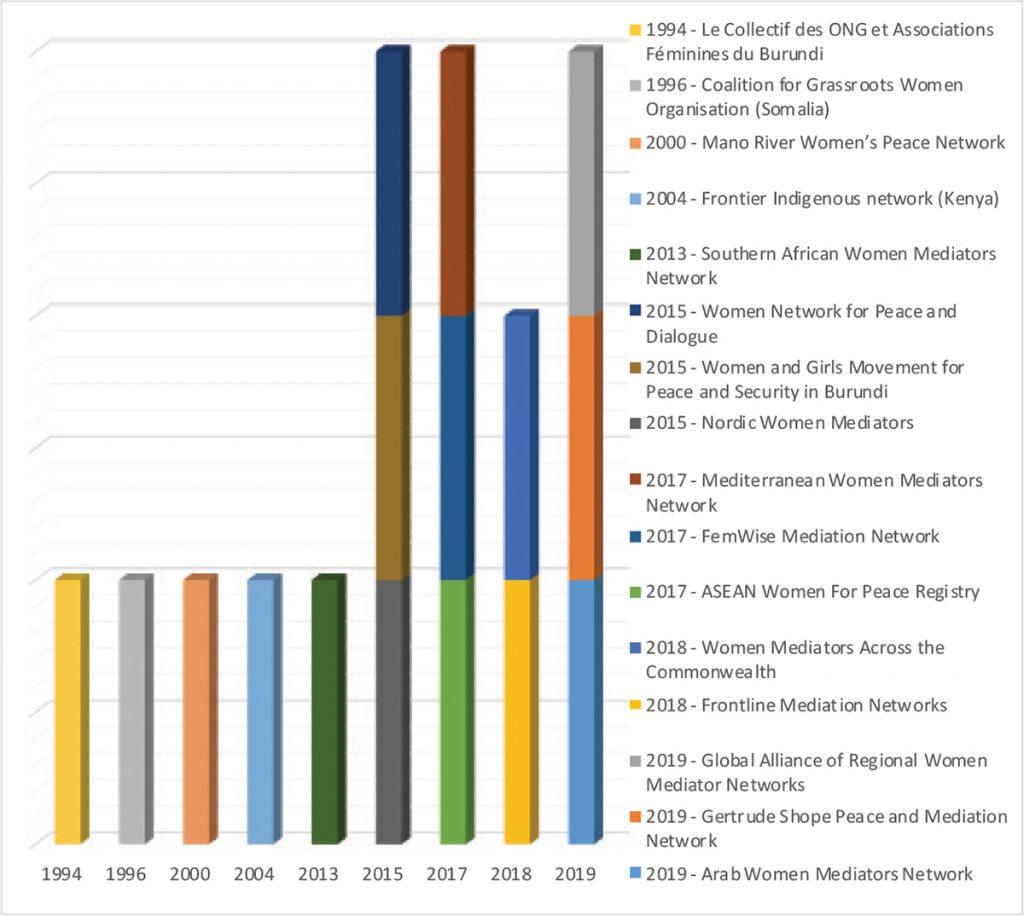

For the greater part of the last two decades, the formation of WMNs across the continent has been sporadic and often in response to crises at a local or regional level. However, a new generation of these WMNs has systematically emerged over the past five years. These WMNs build for peace among women, but at a regional and international level and with the overarching objective to implement the WPS Agenda (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: The emergence of WMNs over the past five years[ix]

How do these WMNs work towards the WPS Agenda?

WMNs bring together and link women with experience in all three tracks of diplomacy. The principal activity of WMNs is to connect mediation actors across geographical locations. WMNs are strengthened by the diversity of their members, and it is also these features that define the scope and focus of each network, as shown in Text Box 1.

Text Box 1: The new generation of WMNs

| Nordic Women Mediators (NWM)[x]

Country Representation: Finland, Norway, Sweden, Denmark, and Iceland. Membership: Nordic women with diverse professional experiences ranging from foreign affairs and international law to multilateral or regional organisations. Objective: The mission of the network is to connect and enable Nordic women mediation actors to collaborate in advancing the inclusion and meaningful participation of women in all phases of peace processes to contribute to achieving sustainable peace. |

| Mediterranean Women Mediators Network (MWMN)[xi]

Country Representation: Albania, Algeria, Andorra, Bosnia-Herzegovina, Cyprus, Croatia, Egypt, France, Jordan, Greece, Israel, Italy, Kosovo, Lebanon, Libya, Malta, Morocco, Monaco, Montenegro, Palestine, Portugal, San Marino, Slovenia, Spain, Tunisia, and Turkey. Membership: Women mediators and peacebuilders within the Mediterranean region. Objective: The MWMN has worked to expand access and space and enhance the deployment of women mediators on mediation platforms. As a response to the complex socio-economic landscape of the Mediterranean area, MWMN believes that these women mediators have a responsibility to offer strategic knowledge and expertise that contributes to conflict resolution and the overall sustainability of peace in the region. |

| Southeast Asian Network of Women Peace Negotiators and Mediators (SEANWPNM)[xii]

Country Representation: Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) Member States. Membership: Women mediators and peacebuilders from the ASEAN region. Objective: This platform connects Southeast Asian women with experience in mediating, negotiating, and facilitating peace processes to contribute to the maintenance of peace and stability positively. They operate within and beyond the ASEAN region. |

| Women Mediators Across the Commonwealth (WMC)[xiii]

Country Representation: Commonwealth nations. Membership: Women mediators from the Commonwealth Member States. Objective: The WMC is a network that prides itself in collecting mediation experiences from a variety of locations in a quest to learn from one another. By bringing together women from various backgrounds, the principal mandate of this network is to act as a platform for peer-to-peer exchange and knowledge sharing among members of the network. |

| Arab Women Mediators Network (AWMN)[xiv]

Country Representation: Arab Member States. Membership: Arab women from all Member States who have the expertise and leadership capacity to take part in mediation and peacebuilding efforts. Objective: The AWMN acts as a network that advocates for the meaningful inclusion of Arab women within peace processes. It allows Arab women to share their expertise in conflict prevention and peaceful settlement in the region, considering the lessons of women who have been involved in the establishment of peaceful solutions to conflict. |

| Global Alliance of Regional Women Mediators Network (Global Alliance)[xv]

Representation: Global. Membership: Regional networks of women mediators, including the NWM, MWMN, SEANWPNM, WMC, and FemWise-Africa (discussed in detail in Text Box 2). Objective: The Global Alliance aims to ensure strengthened complementarity, cooperation, and coordination among the networks. It aims to embody a collective voice to amplify the common goal of enhancing women’s meaningful participation and influence in peace processes at all levels. The Global Alliance also seeks to maintain each network’s independence and characteristics, especially as an increasing number of countries and multilateral organisations are expressing interest in setting up or supporting similar initiatives. |

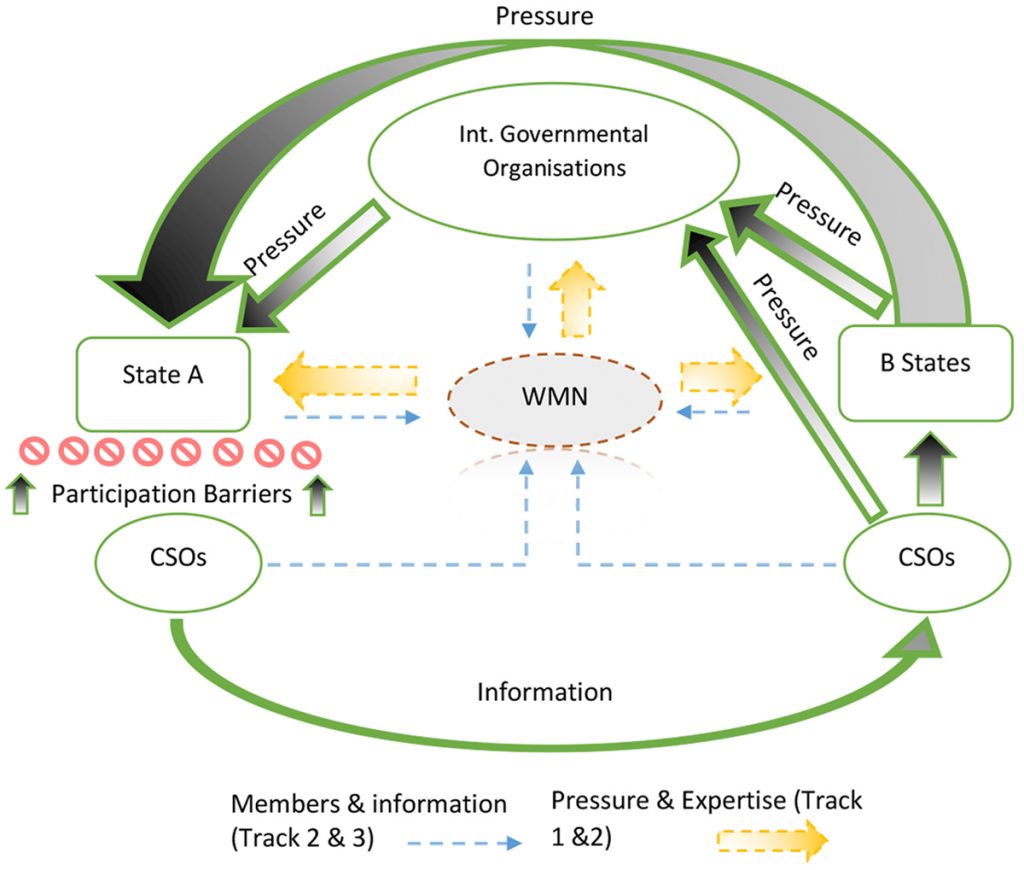

WMNs contribute similarly to the WPS Agenda by connecting high-level diplomacy to more local formal and informal discussions about human rights and cultural, social, and political arrangements. Figure 2 illustrates WMNs’ connections and interactions.

It is apparent that many WMNs already have significant legitimacy, and they have been formally recognised at the launch of the Global Alliance in September 2019. At the launch, the Office of the UN Secretary-General, UN Women, and numerous foreign ministers made their support for and commitment to the success of these networks clear.[xvi] As a result, the resources they have invested in collecting experiences from multiple locations have already begun generating meaning around their thematic focus.

Figure 2: Mapping where WMNs fit into the ‘Boomerang Pattern’ of influence[xvii]

Ultimately, the goal of WMNs is to build systems capable of reliably supplying gender-sensitive support and enhanced gender mainstreaming to facilitate the active inclusion of women mediators at all levels. To achieve this, WMNs work to expand access and space and to enhance an organisational platform on which women mediators can be deployed. They also serve simultaneously as a repository of women experts in peace and security and as champions dispelling the myth that there are no experienced women mediators.

A key indicator of how WMNs are closing the gaps in peace efforts is their success in ensuring women have the necessary skills and opportunities to participate. The FemWise case study below is an example of how this looks in practice.

Text Box 2: Case Study: FemWise-Africa in Action

The Network of African Women in Conflict Prevention and Mediation (FemWise-Africa) is the largest continental WMN to date. The network was established as an outcome of a 2010 long-term study and action plan to eradicate sexual violence against women and children in armed conflicts initiated by the AU Panel of the Wise. FemWise-Africa was officially endorsed by the AU during the 29th Assembly on 4 July 2017.[xviii] The network provides a platform for strategic advocacy, capacity building and networking aimed at enhancing the implementation of commitments to the inclusion of women in peacemaking in Africa. FemWise-Africa’s objective is to strengthen the role of women in conflict prevention and mediation efforts in the context of the African Peace and Security Architecture (APSA).[xix]

The network is chaired by Her Excellency Catherine Samba Panza, former President of the Central African Republic, and Her Excellency Dr Speciosa Wandira, the first African woman Vice-President (Uganda). FemWise-Africa has 462 African women members, and this number continues to grow. Members represent both current and past Heads of State, diplomats, academics, directors of CSOs, and local women peacebuilders.[xx]

In just three years, the network has been able to establish its organisational parameters, infrastructure, and operations for the capacity building, experience sharing, and deployment of women mediators. Examples of FemWise-Africa’s successes are discussed below.

- In the first half of 2020, FemWise-Africa deployed Ms Hope Kivengere and Ms Naima Korchi to Khartoum, Sudan. Ms Nothondo Maphalala was also deployed to Juba, South Sudan. All three women worked with the AU Liaison Offices to provide their expertise in the respective peace processes.[xxi]

- From October to December 2020, the AU and FemWise-Africa’s Secretariat, in partnership with the African Centre for the Constructive Resolution of Disputes (ACCORD) and Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency (Sida), hosted the FemWise-Africa Capacity Building Initiative. Focused on building the capacities of women at the Track III level, the training sessions provided introductory peacebuilding training and skills assessments, while also offering the opportunity to bring together various individuals from the Track I level during Knowledge Sharing sessions. By the end of the 11-week training period, the initiative had reached 180 FemWise-Africa members.

- In December 2019, the FemWise-Africa network decided to decentralise by establishing Regional and National Chapters across the continent. The move was made to integrate regional and national networks into the Regional Economic Communities/Regional Mechanisms (RECs/RMs) and National Peace Infrastructures with their agendas and programmes, while sharing the vision and mission of the network. During the third quarter of 2020, the FemWise-Africa secretariat held regional consultations to engage FemWise-Africa members on the establishment of these National and Regional Chapters.[xxii]

In the international and regional arenas, the WPS Agenda is beginning to cascade effectively and few, if any, organisations would directly oppose its internalisation. However, with regards to peace and security, and especially with trends of increasing intra-state and localised conflict, WMNs will need to gain proficiency and influence at the national and sub-national levels. This will not be an easy task, since it is at these levels where women mediators are most likely to confront their normative rivals, and they will have to grapple with questions of how to enable effective participation of individuals and organisations at the grassroots level in a complex deliberative process. The extent of this challenge can be seen in the fact that no multilateral body involved in the peace and security field has come to a reliable solution. FemWise is establishing and connecting national and regional nodal points, and their organisational DNA is constituted of members from CSOs at various levels and in various States and intergovernmental bodies. Therefore, this new generation of WMNs promises to increase women’s meaningful participation and could help amplify local voices in peace processes.

Recommendations

The PPB has identified several key challenges and correlated priority actions and areas of additional research, including:

- Limited or inaccessible funding for local CSOs, especially those focusing on women and their participation in building more conflict-resilient societies.

- Limited synergies between the WPS Agenda and health and reproductive rights.

- Women CSOs are not meaningfully engaged in decision making.

- Limited coordination between international actors and women-focused CSOs.

- Capacity-sharing and building opportunities favour regional and continental agendas over CSO priorities.

- Insufficient accountability to and for local CSOs.

WMNs are establishing themselves as platforms to consolidate and coordinate the power of women’s organisations at the various stages of their members’ careers and on their levels of diplomacy.

To encourage this ‘pipeline’, the following actions are recommended:

- In recognition of the utility of WMNs in contributing to women’s meaningful participation, donors who support the WPS Agenda need to create more tailored, accessible, and sustained funding oppor-tunities designed for individual WMNs and their affiliated organisations.

- Current WMNs are well suited to experience-sharing activities and could develop this ability further by creating early warning mechanisms. To enhance their ability to share experiences and develop such mechanisms, WMNs should have a well-established network of nodal points in their region. Moreover, a WMN would require a user-friendly system to encourage communication within the network, regardless of their members’ technical ability. Through the establishment of a communication system between regional nodal points, WMNs will be able to produce information quickly and effectively. It will also be crucial for this system to have effective decision-making that requires a level of permanence in its structure to assess and escalate information, solutions, and decisions reliably to the networks’ more politically senior members.

- More strategic investment in capacity-strengthening and capacity-sharing oppor-tunities for WMN members is required, especially at the local level. This should align with the learning priorities of the beneficiaries. Through these more focused sessions, the duplication of work can be reduced. This is possible within a WMN because the outputs of capacity-building sessions can feed back into the network.

- WMNs are serving as effective and central meeting points for women-focused organisations with varying capacities. By embracing the principles of the Grand Bargain,[xxiii] WMNs may be able to lessen the burdens of strict funding application and reporting requirements on local CSOs.

- In terms of monitoring and evaluation, the Continental Results Framework for Reporting and Monitoring on the Imple-mentation of the WPS Agenda in Africa (2018-2028) can incorporate indicators to monitor the development, support, funding, achievements, and deployments of members from the networks, such as FemWise-Africa.

- Sexual and Reproductive Health Rights (SRHR) considerations are largely absent in the WPS Agenda and WMNs discussions. WMNs can support an explicit reference to SRHR in their tenets and build on the UNSCR 2493 (2019) text that contains references to SRHR.[xxiv] These actions will help remove barriers to participation and counter gender stereotypes.

Conclusion

The emergence of WMNs provides an opportunity to address the remaining barriers to the meaningful inclusion of women in peace processes. According to empirical evidence, this will increase the durability of agreements and the prospects of achieving sustainable peace. As the world and Africa grapple with the COVID-19 pandemic and the potential peace and security disruptions, the proliferation of WMNs comes at a crucial moment. The pandemic will potentially exacerbate insecurity at the local level and, therefore, it will be local peacebuilding efforts and WMNs that will be some of the most important mitigation mechanisms.

The Authors

James Murray is a Programmes Officer at Amref Health Africa UK and has been working in the field of peace, security, and development in Africa for the past 4 years. Over this time, he has collaborated with local partners, civil society, national and international stakeholders, and experts working on conflict resolution, women, peace and security, and sexual and reproductive health rights projects and policy. His research interest is in norm entrepreneurship and investigating how grassroots and international best practices can come together to create more effective, meaningful, and lasting security for communities in Africa.

Molly Hamilton is the Women, Peace and Security Programme Officer at ACCORD. Prior to joining ACCORD in 2019, she obtained her Bachelor of Arts Degree cum laude with a major in Political Science and minor in Women and Gender Studies from Mount Allison University, New Brunswick, Canada. Her areas of interests include women, peace and security and more specifically, countering sexual violence and gender-based violence.

Kundai Mtasa is a Programme Officer at ACCORD. Prior to joining ACCORD, she attended the University of Pretoria where she earned an undergraduate degree in Politics and International Studies and an honours degree in Development Studies. Shortly after, she went on to pursue a master’s in Leadership and Development at King’s College London and was an Associate Fellow at the African Leadership Centre. Previously, she has worked with UNICEF and has also conducted research on human trafficking of young women and girls in South Africa. Her interests include women and children, human trafficking, education and social development.

Endnotes

[I] Peace agreements are 35% more likely to last at least 15 years if women are engaged. O’Reilly, M.,

Ó Súilleabháin, A. and Paffenholz, T. 2015. Reimagining Peacemaking: Women’s Roles in Peace Processes. New York: International Peace Institute. Available from: <https://www.ipinst.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/IPI-E-pub-Reimagining-Peacemaking.pdf> [Accessed 4 August 2019].

[ii] O’Reilly, M. 2018. Women write better constitutions. Available from: <http://foreignpolicy.com/2018/02/23/women-write-better-constitutions> [Accessed 4 August 2019]. This study provides evidence showing that the low participation of women in peacemaking and formal peace negotiations results in low participation in peacebuilding actions. The study found that “only 1 in 5 constitution drafters in conflict settings is a woman… because the rules for electing or appointing a constitution-making body are typically established in the peace process — an even more male-dominated affair.”

[iii] UN Women. 2012. “Women’s participation in peace negotiations: Connections between presence and influence.” Available from: <https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/03AWomenPeaceNeg.pdf> [Accessed 11 November 2019].

[iv] FAS was founded by African women leaders in 1996 in Geneva to prevent and resolve conflicts in Africa and to empower women for leadership.

[v] Makan-Lakha, P. and Yvette-Ngandu, K. 2017. The Power of the Collectives: FemWise-Africa. Durban: ACCORD. Available from: <https://accord.org.za/publication/the-power-of-collectives> [Accessed 16 March 2021].

[vi] https://www.inclusivepeace.org/content/mano-river-women’s-peace-network-marwopnet

[vii] Makan-Lakha and Yvette-Ngandu. 2017. The Power of the Collectives.

[viii] Relief Web. 2012. “President Sirleaf discusses Liberian women’s involvement in peacemaking and peacebuilding.” Press Release, 1 October. Available from: <https://reliefweb.int/report/liberia/president-sirleaf-discusses-liberian-women%E2%80%99s-involvement-peacemaking-and> [Accessed 16 March 2021].

[ix] Compiled by Authors.

[x] A Global Alliance of Regional Women Mediator Networks. 2019. Nordic Women Mediators (NWM). Available from: <https://globalwomenmediators.org/nwm> [Accessed 26 February 2021].

[xi] Mediterranean Women Mediators Network. 2017. Mediterranean Women Mediators Network. Available from: <https://womenmediators.net/membership> [Accessed 27 February 2021].

[xii] Barnett, M.N. 1999. Culture, strategy and foreign policy change: Israel’s road to Oslo. European Journal of International Relations, 5(1): 5–36.

[xiii] A Global Alliance of Regional Women Mediator Networks. 2019. The Women Mediators across the Commonwealth. Available from: <https://globalwomenmediators.org/wmc> [Accessed 26 February 2021].

[xiv] A Global Alliance of Regional Women Mediator Networks. 2019. Arab Women Mediators Network. Available from: <https://globalwomenmediators.org/awmn> [Accessed 26 February 2021].

[xv] A Global Alliance of Regional Women Mediator Networks. 2019. Global Alliance Concept Note. <https://globalwomenmediators.org/#partners> [Accessed 26 February 2021].

[xvi] UN Web TV. 2019. Launch of the Global Alliance of Women Mediator Networks. Available from: <http://webtv.un.org/search/launch-of-the-global-alliance-of-women-mediator-networks/6090032915001/?term&fbclid=IwAR2AC5vOVzcnweFZOSaAkXI_xEqd87KEeooMH8nUgsN0sxlgbjYdfMWUKwg> [Accessed 1 March 2021].

[xvii] Authors’ adaptation of Keck, M. and Sikkink, K. 1998. Activists Beyond Borders: Advocacy Networks in International Politics. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, p. 13. The Boomerang Pattern serves to visualise the interaction between domestic human rights NGOs and CSOs in (predominantly developing) countries with uncompromising governments and their international allies. These concepts are further explored in literature on Transnational Advocacy Networks.

[xviii] Makan-Lakha and Yvette-Ngandu. 2017. The Power of the Collectives.

[xix] Ibid.

[xx] FemWise-Africa Secretariat. 2020. FemWise-Africa Quarterly Newsletter, 1(1). Available from: <https://www.peaceau.org/uploads/femwise-africa-newsletter-first-volume-first-issue.pdf> [Accessed 15 February 2021].

[xxi] Ibid.

[xxii] Ibid.

[xxiii] The Grand Bargain is a strategy emerging from the 2016 Humanitarian Summit, which brought significant global attention to the localisation agenda. It committed international donors and organisations to allocate 25% of humanitarian funding to local and national organisations by 2020.

[xxiv] UN. 2019. “Security Council urges recommitment to Women, Peace, Security Agenda, unanimously adopting Resolution 2493 (2019).” Available from: <https://www.un.org/press/en/2019/sc13998.doc.htm> [Accessed 13 May 2021].