Introduction

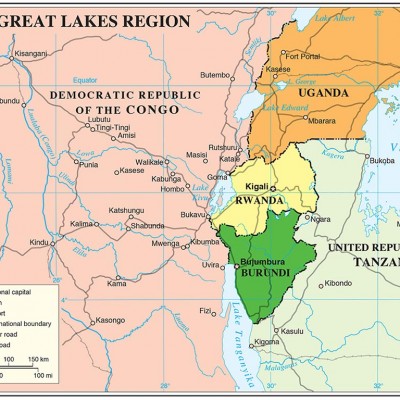

The Great Lakes Region of Africa is characterised by ongoing conflict. The region has been – and continues to be – a theatre of some of the most intractable, perverse and turbulent violent conflicts on the continent. These violent conflicts occur at two levels – intrastate conflicts (with great regional effects), and cross-border (interstate with intrastate ramifications) cyclic violence – which bear manifestations of never-ending problems of displacements and refugees, illegal exploitation of resources and human trafficking, growth of illegal armed groups and the upsurge of small arms and light weapons. This intrastate–interstate conflict web is closely linked to situations of poor management challenges around refugees and displaced persons, who harbour feelings of revenge and often cross back to their countries, seeking to retake power.

Issues of exclusive negative sectarian cleavages; poor and unconstitutional management of political governance and transitions; and irresponsible and unstructured development, management and distribution of resources are key to the sustained violent conflicts in the region. This is evident in the example of the fall of the Democratic Republic of the Congo’s (DRC) president, Laurent Kabila – who, after toppling Mobutu Sese Seko in 1997 with the help of Uganda and Rwanda, had “cupidity for power rather than governance which led him to political choices that were fraught with, among others, the citizenship dilemmas of his predecessor”.1 The issues above are some of the factors that have led the region to be described as “the most unstable… with protracted violent conflict and instability… manifesting as trans-boundary inter-communal violence with… election-triggered and political violence, and violence against civilians”,2 with a myriad displaced persons and destroyed infrastructure as key features.

One way of deepening understanding of conflicts in the region would be to narrow down the named factors into specific theories. Four theories can be isolated: “political theory (competition for the control of state power); human needs theory (people are fighting in search of better living conditions); relational theory (conflicts are caused by identity related problems) and transformational theory (demand for change against resistance to change)”.3 Indeed, one of the violent conflict cases that cut across these theories is that of Rwanda’s conflict, which reached its climax in the 1994 genocide. Examining the causes of violent conflict in that country, it is observed that violence between Hutus and Tutsis “is connected with the failure of Rwandan nationalism to transcend the colonial construction of Hutu and Tutsi as native and alien respectively”4 – hence the continued struggle for state power along identity lines, and demanding change against resistance to change. Seeking to identify key factors along these identity lines and the redefinition of power created a framework or approaches through which stakeholders could develop and implement complementary, multipronged, collaborative efforts for peace and effective conflict management systems. These ranged from intrastate actors to interstate (regional) approaches, as well as non-state or civil society contributions. In furthering the argument of complementary collaborative efforts, the International Peace Academy, at its policy seminar on the Great Lakes Region – which took place in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania, on 15–17 December 2003, with the theme ‘Peace, Security and Governance in the Great Lakes Region’ – pointed out that prospects for the consolidation of peace in the region would depend on an empowered civil society, strongly institutionalised and efficient subregional organisations, and strategic interventions by the international community. The Great Lakes Project (GLP), a collaborative framework by three organisations – the African Centre for the Constructive Resolution of Disputes (ACCORD) in South Africa, the Global Partnership for the Prevention of Armed Conflict (GPPAC) in the Netherlands, and the Nairobi Peace Initiative – Africa (NPI-Africa), based in Kenya – developed a three-year project in 2012: ‘Consolidating Peacebuilding in the Great Lakes of Africa’.

Great Lakes Regional Conflict and Prevention Architecture

As has been discussed, it is clear that the conflict landscape in the Great Lakes Region cannot be comprehensively understood and addressed without looking at the internal social, political and economic dynamics in the respective countries. This implies identifying and examining the domestic and regional dynamics that facilitate situations of both sectarian repression and widespread manipulation. These then give rise to identity-based struggles in the region, which find their strength in “idealised representation of ethnicity that, inter alia, become characterised by ethnic polarisation and politicisation of ethnicity”.5 These challenges call for the development of counter-narratives on social identity to the current narrations that have been inappropriately presented. This challenge is captured well by looking at the situation of Rwanda, where “for the period up to 1860, it is [was] correct to say that historians knew next to nothing about how the terms ‘Twa’, ‘Hutu’ and ‘Tutsi’ were used in social discourse or physical classifications”.6

In looking at the role of social identity, it is noteworthy to seek the meaning and place of ‘identity’ within the social context of the Great Lakes Region. Identity can be viewed as a social and conceptual phenomenon and described as “the way individuals and groups define themselves and are defined by others on the basis of, among others, ethnicity, culture and religion… [and which] conceptually gives a deeply rooted psychological and social meaning to the individual in the context of group dynamics”.7 This describes the situation of the Great Lakes Region in regard to the theories highlighted earlier. Based on this, it can be argued that expressions of solidarity alongside common identities, as communities struggle for and pursue control of political power against each other within and outside defined national boundaries, are a common feature in the region. In simple analogy, a person or group of ethnicity A in country B will feel more ‘connected’ to a person or group A living as refugees in country C, rather than a person or group of ethnicity D in country A.

It is also necessary to identify, analyse and examine the challenges that exist within the regional conflict prevention architecture. These include the African Union (AU), the East African Community (EAC), the Economic Community of Central African States (ECCAS), the International Conference on the Great Lakes Region (ICGLR) and the Southern African Development Community (SADC). These organisations have defined peace and security architectures, most of which are in the form of protocols. However, several challenges in the application of these institutions towards the full realisation of peace – some cross-cutting, and others embedded in these structures – have emerged.

One cross-cutting challenge is that these structures do not speak to and complement each other, and hence only promote territorial protectionism. This element of competition can be illustrated by looking at the situation in 1998, when the DRC’s President Kabila took his country into the SADC regional bloc – a much stronger rival to the EAC. This action did not sit well with Ugandan president, Yoweri Museveni, who had an idea to revive and make the EAC a stronger regional bloc, and had expected Kabila’s support given Museveni’s role in Kabila’s ascendance to power.8

These regional bodies sound good on paper, but lack austerity in the implementation of the peace agenda in the region. ECCAS, founded on 18 October 1983, has demonstrated infrastructural weaknesses in terms of pursuing issues of peace and security in the region, and well-established structures such as the AU, the ICGLR and the EAC have critical gaps in translating their protocols to the pursuit of peace. Two examples can be noted. First, while the role of non-state actors is advocated through Article 127 of the Treaty for the Establishment of the East African Community, there is only a mention that “the partner states agree to provide an enabling environment for the private sector and civil society to take advantage of the community and… among others… promote a continuous dialogue with the private sector and civil society at the national level and that of the community…”,9 with no clear implementation plan and accountable framework. Second, in Article 15 of the Protocol for the Prevention and the Punishment of the Crime of Genocide, War Crimes and Crimes against Humanity and All Forms of Discrimination, for example, the ICGLR identifies civil society as a major actor in the area of prevention of genocide, war crimes and crimes against humanity, but only briefly mentions the aspect of collaboration with civil society. Other examples also highlight the importance of conflict prevention – for example, the EAC Protocol on Peace and Security puts ‘prevention’ as central and, in particular, Article 4 concentrates on Conflict Prevention, Management and Resolutions (CPMR). Two challenges arise here: one, there is a deliberate lack of strategies and accountable systems to ensure that these protocols are followed and governments are held responsible in their failures; and two, in spite of realising the need to target and involve ex-combatants or former members of militia groups in conflict prevention and peacebuilding, no protocol or express action has been developed and/or undertaken in its accomplishment. From these challenges emerge two further issues: the continuous shrinking spaces for civil society; and conflict relapses as a result of unstructured and uncoordinated regional disarmament, demobilisation and reintegration (DDR) programmes.

Spaces for Capacity Building and Collaboration for Peacebuilding

To develop, situate, advance and comprehensively implement capacity building and principles of collaboration for peacebuilding in the Great Lakes Region requires one to understand both local dynamics and contexts as well as the emerging regional and global political and economic trajectories. To address the conflict challenges understood by the previously identified theories – political, human needs, relational and transformational – it is important to develop and undertake approaches that take into cognisance the gaps and institutional blockades in the regional bodies, as previously illustrated. This should include identifying and providing mechanisms for solving challenges that “characteristically involves or generates hegemonic-directed competition, cooperation and conflict, under conditions of scarcity, about who should control the state and direct its core functions of authoritative regulation, allocation, and distribution through its presumed monopoly of physical force and policy directives”10 on one hand, and citizen participation in political affairs of respective countries and regional affairs on the other.

There exist many structures – both state and non-state – that work in the area of conflict resolution and peacebuilding. These include intrastate bodies, such as the EAC, AU and ICGLR, with the express mandate of mobilising state efforts in building a peaceful and economically progressive and stable region.

Taking into consideration the regional context of conflict relapses and the existing conflict prevention architecture and peace infrastructures, any capacity building for conflict prevention and peacebuilding approaches must address the following key areas:

- lack of structure and coordinated state and non-state actors’ joint regional conflict analysis and intervention approaches;

- inadequate civil society organisation (CSO)-intergovernmental approaches to addressing specific conflict drivers in the region;

- understanding of, and participation in, intergovernmental peacebuilding and conflict mitigation and policies;

- identifying, developing and/or enhancing the existing common peace values; and

- mobilising and developing the capacities of local communities, especially those living across and along the borders, to appreciate and utilise intergovernmental structures in peacebuilding, peacemaking and conflict mitigation.

Since it was formed, the GLP, through assessment, has successfully identified challenges to peace and responses to conflict among CSOs in the region, and has created various platforms, including the National Civil Society Forum (NCSF) and its regional structure, the Regional Civil Society Forum (RCSF), to effect structured coordination with the ICGLR, among others, in conflict prevention. At the initiation of the project, a baseline survey was carried out. Affirming some of the challenges above, this baseline survey determined the following key issues that impede the full contribution of CSOs to regional stability:

- unfavourable and/or shrinking spaces for the CSOs – for example, there are very few CSOs operating in Rwanda (confirmed by the very few CSOs that responded to the baseline surveys conducted in 2013) while in Uganda, the CSOs that responded confirmed the emergence of government-initiated laws that restrict their free operation;

- some of the countries in the region do not have national structures that coordinate their peacebuilding efforts, and at a regional level, uncoordinated CSO efforts contribute to the lack of effective influence on regional interstate bodies, such as the ICGLR, towards the peace agenda;

- inadequate capacities to engage with and effectively address continuous and ever-changing conflicts in the region; and

- uncoordinated conflict prevention and regional approach in conflict analysis and programming.

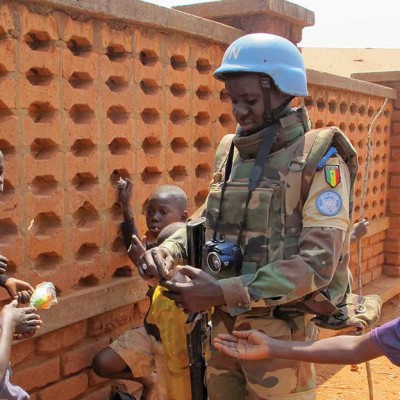

Considering the previous points, addressing and/or avoiding the re-emergence of violent conflicts in the region – or even undertaking comprehensive conflict prevention – is a big challenge overall. One factor that contributes further to the challenge is the lack of local ownership of various interventions, including United Nations (UN)-related peace work. For example, the UN peacekeeping mission in the DRC (MONUSCO) was established in 1999 but has never received total community acceptance, due to its alleged failure to protect citizens from attacks, such as from the Lord’s Resistance Army. Therefore, arguments such as “embedded multilateralism… an institutionalised but nuanced mechanism of collaboration between the UN and regional organizations in multiple issue-areas”11 as a means that can facilitate the avoidance of conflicts in the region, need further thought and development. To have effective conflict prevention strategies in the region, such UN-regional organisations engagement must be supported by structured involvement of CSOs. Among other things, this would ensure that the principles, values and vision of a conflict-free society is not only at the level of leadership, but is commonly owned and shared at a local level. For this to happen, CSOs must have the capacity to engage and participate in such approaches. The question is how CSO frameworks, such as the GLP-created National and Regional Civil Society Forums, can remain focused and sustainably pursue what benefits a society in political dilemmas, such as the current Burundi turmoil. Another question is how those CSOs can avoid internal leadership struggles, which can threaten their operations to the extent of them fragmenting.

Strategies that focus on the contribution of CSOs in the building of regional capacity for conflict prevention and peacebuilding in the Great Lakes Region must take into cognisance the internal and external challenges discussed here. The approach must include enhancing capacities and deepening the understanding of conflict analysis; the development and implementation of intervention strategies; and the sharpening of skills in joint lobbying and advocacy for conflict prevention. In addition, the ability of CSOs in building/forming, managing and leading multi-issue frameworks – such as the forums guided by the development and implementation of a common vision, principles and values of peace and conflict prevention – can ensure sustainable joint approaches. Once the frameworks have been built and principles of operations adopted, capacity enhancement development must consider how CSOs, at national and regional level, can effectively engage in and influence contemporary conflict management processes, such as peace or cessation of hostilities agreements. This can enhance interrogative, local ownership and the monitoring of such agreements, which ultimately contributes to the eradication of multiple interpretations – such as the failure to implement the Burundi Arusha Accord, signed in 2005 by conflict parties in Burundi and which apart from facilitating the end of violence, among other things, contained specifics on the presidential term limits. Failing to adhere to the provisions of the agreement and the constitution due to, inter alia, the vigilante role of non-state actors, including CSOs, plunged the country into a crisis in 2015.

Conclusion

In conclusion, regional capacity for conflict prevention and peacebuilding in the Great Lakes Region must look “beyond ending violent conflict… and seek to create the capacity for a culture of just peace which requires people to know how to take responsibility for shaping their culture and all of their society’s architecture, including structures, institutions, policies, and organizations that support it”.12 This implies not only having a common agenda for regional peace through common principles, values and operative policies, but also developing long-term, issue-oriented plans. These plans must resonate well with the needs and desires of the communities. Linking actions with, and continuous interrogation of, national and regional processes – including those of regional interstate bodies such as the ICGLR and EAC – must also be undertaken. The established national and regional CSO forums must be viewed as effective vehicles towards stability in the Great Lakes Region.

Endnotes

- Adibe, Clement E. (2003) Do Regional Organizations Matter? Comparing the Conflict Management in West Africa and Great Lakes Region. In Bouldon, Jane (ed.) Dealing with Conflict in Africa – The United Nations and Regional Organizations. New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan, p. 96.

- Ibid., p. 5.

- Shyaka, Anastase (2008) Understanding the Conflicts in the Great Lakes Region: An Overview. Journal of African Conflicts and Peace Studies, 1 (1), pp. 5–12.

- Mamdani, Mahmood (2001) When Victims Become Killers – Colonialism, Nativism and Genocide in Rwanda. Princeton: Princeton University Press, p. 34.

- Pottier, Johan (2002) Re-Imagining Rwanda – Conflicts, Survival and Disinformation in the Late Twentieth Century. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press, p. 112.

- Ibid., p. 13.

- Deng, Francis M. (1995) War of Visions: Conflict of Identities in the Sudan. Washington, DC: The Brookings Institution, p. 1.

- John, Clerk F. (2001) Explaining Ugandan Intervention in Congo: Evidence and Interpretation. The Journal of Modern African Studies, 39 (2), p. 276.

- East Africa Community (EAC) (1999) The East Africa Community (EAC) Treaty, Chapter 25, Article 127 1(a), p. 114.

- Jinadu, Adele L. (2007) Explaining and Managing Ethnic Conflict in Africa: Towards a Cultural Theory of Democracy. Uppsala: Universitetstryckeriet, p. 13.

- Adibe, Clement E. (2003) op. cit., p. 80.

- Schirch, Lisa (2004) The Little Book of Strategic Peacebuilding – A Vision and Framework for Peace with Justice. Intercourse, PA: Good Books, p. 56.