Abstract

The clashes between Fulani herdsmen and farmers in Nigeria have become endemic and persistent for decades. Climate change, cattle rustling, expansion of cultivated lands and population growth are among the major drivers of these clashes. However, the trends in the clashes in recent years suggest strong political, religious, ethnic and economic undertones. The recurrent and escalating nature of the violence in recent times is worrisome and despite the existing security efforts at the federal and state levels, the conflict remains unabated. This research examines the farmer–Fulani herdsmen clashes and their impact on the socio-economic development of southern Kaduna state. To explain the multifaceted nature of the clashes and how they affect the livelihoods of the affected communities, the study employs a theory of frustration and conflict, a quantitative research method, a survey research design and inferential statistics to analyse data. Findings from the research show an intricate interplay of socio-political, economic and ethno-religious factors in the violent clashes, a lack of feasible and realistic grazing policies and a lack of strong political will to address the conflict. Based on the research findings, the study recommends the establishment of cattle ranches in accordance with the existing laws on land ownership and robust security measures and structures to anticipate and forestall the recurrent clashes.

1. Introduction

The farmer–Fulani herdsmen conflict in Nigeria predates the colonial era and the violent clashes between them date back to 1923 (Migeod 1925, cited in Blench, 2001). The persistent clashes over time have resulted in constitutional and political reforms in correspondence with the dynamic pattern of the conflict. Nonetheless, the reforms restricted or limited Fulani herdsmen’s movement and access to green lands in the country, triggering an upsurge of the crisis since the 1980s and 1990s (Blench, 2001). Furthermore, because Nigeria is an agrarian society — in particular the northern part — the farmer–Fulani herdsmen conflict continues to affect the region’s economy adversely (ReliefWeb, 2018), especially agriculture in the affected communities (Adelaja et al., 2023), despite many attempts at the federal, state and local levels to address the issue. The recurring clashes between the two groups also pose a serious threat to Nigeria’s security (Okibe, 2022; Blanchard, 2023), worsen food insecurity (Ijoko et al., 2023) and result in the loss of billions of dollars in annual projected revenue (ICG, 2020).

While much research has been conducted on the farmer–Fulani herdsmen conflict in Nigeria, there is, as yet, no empirical research conducted on the impact of the conflict on the socio-economic development of southern Kaduna, where the conflict has been rampant and violent for many years. Similarly, most research on the clashes relies on qualitative analyses or newspaper reports, limiting objective assessments of the conflict’s socio-economic impact in southern Kaduna. Hence, by adopting a quantitative approach, this research seeks to methodically contribute to the literature by providing measurable, data-driven insights that enhance policy formulation and intervention strategies for sustainable development in the region. Furthermore, while most of the root causes of this conflict are well known to the public and the government, there appears to be a lack of strong political will from the government and the existing policies and programmes aimed at addressing the conflict are relatively ineffective and challenging for failing to adequately consider the fragile ethno-religious, economic and political tensions that often exacerbate the clashes in the affected communities. There is, therefore, a need to investigate why the conflict persists, why it is escalating and how to stop it. Given the aforementioned, the findings of this research seek to contribute to knowledge by identifying practical and feasible policies and approaches to help the government devise strategies to curb the menace and restore peace and stability in southern Kaduna. Furthermore, the degeneration of the clashes can also be ascribed to the economy, which is deeply embedded in the context of the political economy of land-related struggle, as argued by Abbass (2012). While some studies link the clashes to an ever-increasing population, which has intensified the competition for space and land (Olabode and Ajibade, 2010; Adisa, 2012), others associate it with the expansion from the traditional grazing routes into cultivated lands (Akinwotu, 2016; Mikailu, 2016).

2. Contextual discussion

Although there have been several violent encounters between the Fulani herdsmen and farming communities for over two decades (Lacher, 2022), the escalation reached its peak in 2014 (Global Terrorism Index, 2015). More violence that followed in early 2016 was worrisome, as it indicated the spread of the crisis on farming communities in many states in Nigeria, leading to hundreds of thousands of civilian deaths (Akinwotu, 2016; ICG, 2018; Ogu, 2020; Ojewale, 2021; Ibrahim and Eboh, 2023; The Defense Post, 2023).

Therefore, uncovering the multifaceted pattern of the violent clashes, some scholars have pinpointed various factors responsible for the incessant hostilities in Nigeria. One such narrative is that of climate change, which has forced the movement of Fulani herdsmen in search of grazing land and has resulted in the invasion of farmlands across the north-west (Lekan, 2023). In addition, the expansion of cultivated lands by farmers, extensive sedentarisation, burning of rangelands, drought and overgrazing have also been propounded among the main factors fuelling the clashes (Blench, 2001; Folami, 2009; Ofuoku and Isife, 2009; Adekunle and Adisa, 2010; Adisa, 2012; Odoh and Chigozie, 2012; Audu, 2013; Bello, 2013; McGregor, 2014; Okeke, 2014).

However, the trends in the clashes in recent years suggest strong political, religious, ethnic and economic interplays (CAN, 2018; Emmanuel, 2021; Ikyernum, 2023). Many reports and commentaries suggest the involvement of some political elites from the north who fuel the clashes for political and business interests. Politically, the conflict is used as a tool to destabilise communities considered hostile (Akinkuotu, 2016) or against the northern political (‘Fulanisation’ or Islamisation) agenda (Nathaniel, 2023). The core political factor that undermines efforts to resolving the clashes is the failure of governance across all levels. Key policies aimed at addressing the conflict have proven difficult to be enforced or implemented from the national to local governments. Several laws for regulating land use, grazing and migration of herdsmen in the state boundaries in Nigeria lack proper implementation strategies. Good examples of such laws are the National Grazing Reserve Bill (2016) and the Rural Grazing Area (RUGA) — an initiative introduced in 2019 to establish resettlements for herders to provide livestock management and reduce conflict. Both laws were widely unpopular in many states, particularly in the southern region, where people regard the 2016 Bill as a land-grabbing strategy by the northern elites and a threat to their autonomy (Egbuta, 2018; Fasan, 2019; Nathaniel, 2023). The violence is further worsened by the state and local governments’ inability to maintain stability in the conflict zones for either lack of adequate resources and commitment or synergy in the security infrastructure to deal with the issues of land disputes, ethnic grievances and migration issues (Ugwueze et al., 2022). Moreover, the resistance against grazing policies by southern states indicates the political polarisation in Nigeria (Ojo, 2022). The varying levels of political will among states in different parts of the country result in disjointed policy enforcement, creating a lacuna in managing the clashes.

Within an economic context, farmers and herders are vulnerable in terms of economic status, but their level of economic marginalisation is disproportionally distinct. While herders often enjoy political and financial favours and support in the form of subsidies and protection from the federal government, farmers, particularly in southern Nigeria, are left grappling with economic vulnerabilities and limited access to markets. The disproportionality in economic empowerment between herders and farmers fuels grievances, which are usually violently expressed (Adeyemo and Lawal, 2021; Brottem, 2021). Furthermore, poverty and economic suppression escalate the violent clashes. Farmers with limited access to agricultural technology or financial empowerment are allegedly more inclined to use violence to defend their farmlands against the marauding Fulani herdsmen, who also feel threatened by farmers due to overdependence on their livestock for livelihoods (Ugwueze et al., 2022).

Furthermore, business elites (some of whom are also politicians) from northern Nigeria engaged in the cattle business are alleged to be responsible for the escalation of the clashes, as they supply arms and provide protection to herdsmen, sometimes in connivance with the security agencies. Several incidences in the Middle-Belt and north-eastern regions, including southern Kaduna, seem to back these allegations. These allegations were even worse under former President Muhammadu Buhari’s government due to the level of impunity with which the administration handled the issue, which was often attributed to his Fulani ethnic origins (Akinkuotu, 2016; Okoli, 2016; ICG, 2017; Kunle et al., 2020). Religion also constitutes a potent aspect of the complex nature of the farmer-herder clashes, especially in light of the demographic and geographic intertwinement between largely Muslim Fulani herdsmen and predominantly Christian farmers. This religious predisposition frustrates an unbiased and effective implementation of government policies. Worst still, leaders of Christian and Muslim communities often instigate sentiments by justifying violence to promote religious hegemony, which creates religious polarisation with significant impacts on efforts at reconciliation (Imobighe, 2021). While some religious clergymen have promoted reconciliation and peacebuilding, others perpetuate hatred and resistance against imagined threats to their religion (Osaghae, 2022). This contrasting approach among religious leaders in dealing with the clashes presents a great obstacle towards collective effort to resolving the conflict.

In the case of southern Kaduna, there are a plethora of allegations of bias by successive governments in the state in the handling of the issue in favour of the herdsmen, the worst being under Nasir El-Rufai, the state’s immediate past governor (Shiklam, 2017; Hoffmann, 2023). Additionally, due to the long-existing religious tensions between Christians and Muslims in the north, especially in southern Kaduna, the Fulani-farmer clashes are often linked to religious motives. The persistence and prevalence of attacks on southern Kaduna communities by the Fulani herdsmen compared to other parts of the state tend to validate these allegations. This pattern of attacks is the same across the north-east and Middle-Belt regions. As a result, the conflict has morphed into a religious and sometimes political problem and is often fuelled and intensified by these factors (IRIN, 2010; CAN, 2018; Emmanuel, 2021; Ikyernum, 2023). The culmination of all these factors created serious public distrust and a lack of confidence in the government, especially among the farming communities most affected by the clashes, not only in the north but recently also in the southern region. Thus, there is a shift from previously associated drivers of the conflict from environmental and land-related factors to a political, ethnic and in the case of southern Kaduna, religious one. Consequently, almost all the policies and programmes introduced by the government are viewed either as largely biased or a plot to seize and hand over state land to Fulani herdsmen. Thus, most of the federal government’s anti-open grazing policies have been unpopular and met with outright rejection from the states affected by the clashes, which are undermining efforts to address the problem.

Undoubtedly, these series of clashes have a serious effect on the development of the affected regions and the entire country. Communities where the crisis is endemic, more often than not, find themselves in an economic disaster. The migration to other regions in the country by people in the affected communities has resulted in a displacement crisis. Consequently, farming, businesses and other economic activities degenerate by the day as the bloodshed and violent attacks on individuals and institutions present a hostile business arena for both local and international investment — vital elements of achieving sustainable development (Damba, 2007).

To tackle these endemic clashes, different governments in Nigeria developed several measures at different times but to no avail. One recent example of such efforts is the RUGA project, established in January 2019 to revive the national grazing reserves under the National Livestock Transformation Plan (NLTP). However, it was widely hampered by widespread public rejection, as it was considered a land-grabbing policy (Jinadu, 2021). Furthermore, in the past, the Federal government also committed N10 billion to commission the Great Green Wall Programme (GGWP) to address desert encroachment, a major factor responsible for the migration of the pastoralists from the far north to the north-western region of Nigeria. The project was, however, unsuccessful due to a lack of adequate and sustained funding (Raman, 2023).

In addition, there were several allegations against Buhari’s administration for being complicit in its response to the clashes (Ugwu, 2023). To this end, some states like Ekiti, Taraba and Benue passed the Anti-Open Grazing Bill into law in their respective localities to tackle the Fulani herdsmen menace and demonstrate the deep division between the affected states and the federal government, precipitated by the central government and security agencies’ complacency in the clashes. Given this context, this study was inspired to examine the farmer-herder clashes and their impact on the socio-economic development of southern Kaduna.

3. Methodology

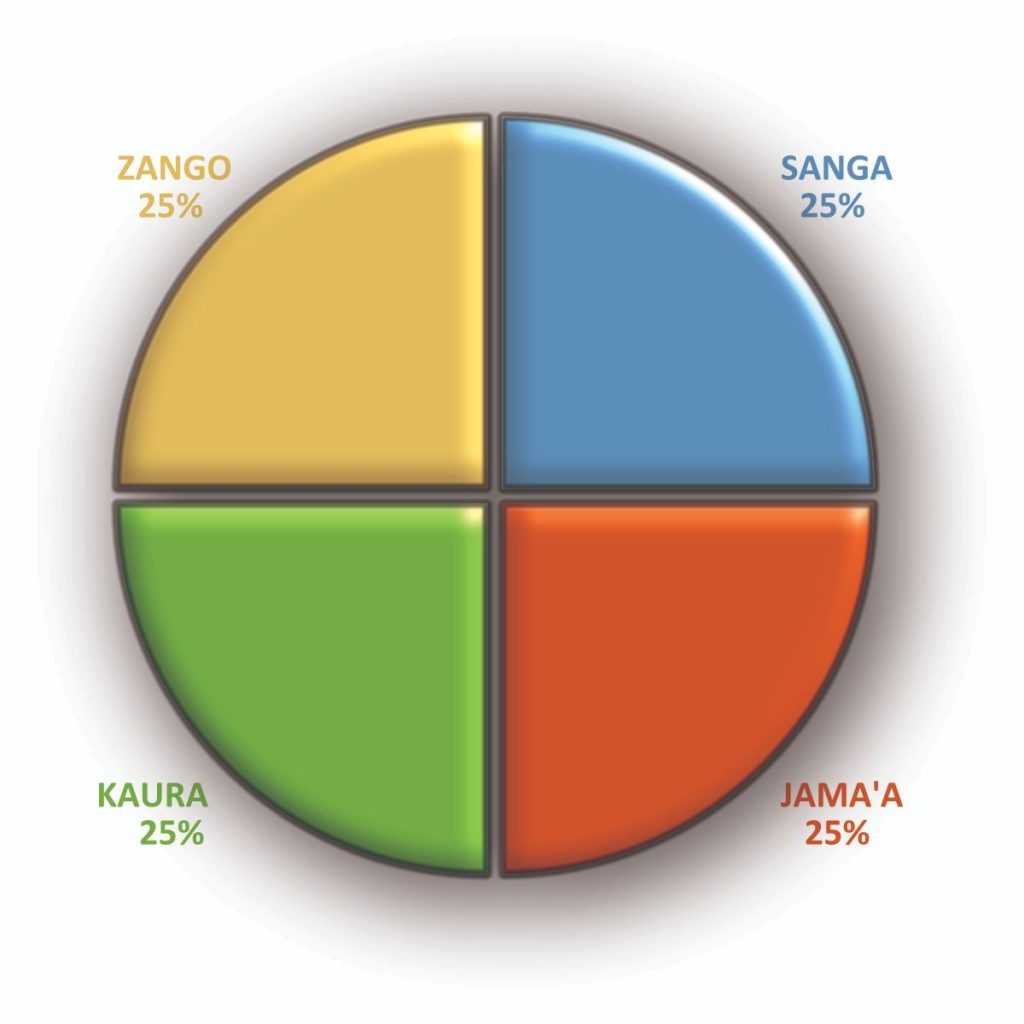

This study adopted a quantitative research method and a survey design and covers the period 2015 to 2024. It took a sample size of 400 from 927 428 — the population of the four local government areas (LGAs) of southern Kaduna. They comprised Kaura (174 262), Jaba (155 973), Jama’a (278 202) and Zangon kataf (318 991) (EWEI, 2019). These four LGAs were chosen because they are the most adversely affected of the eight LGAs in southern Kaduna and have the highest civilian fatalities. Furthermore, the study’s participants are drawn from local farmers (40.8%), peasants (7.8%), civil servants (22%), traders (18.3) and others (11.3%), as they constitute the population directly impacted by the conflict in the region. In addition, the study employed a probability sampling technique and regression analysis with a 95% confidence interval and inferential statistics to analyse data using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS).

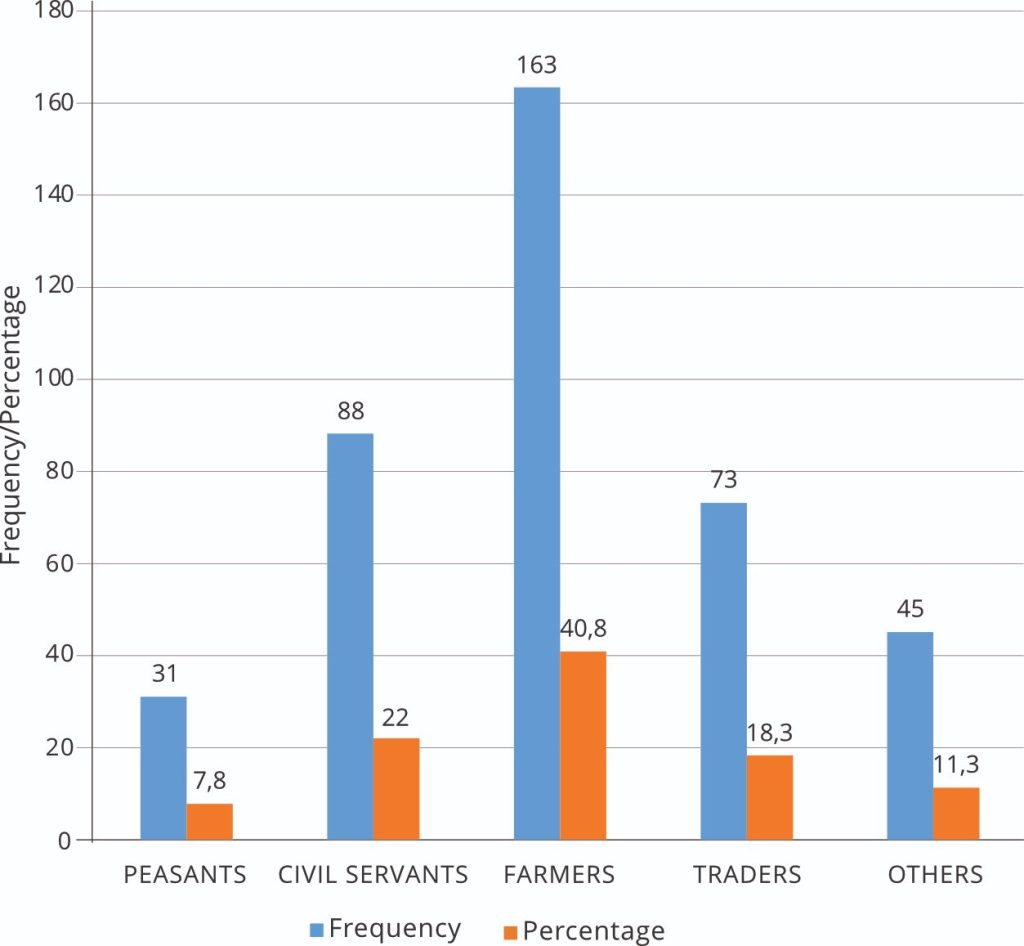

The Partem’s formula below was used to determine the sample size.

Where n = Sample size required

N = total population

D = precision level (0.05).

Z = number of standard deviation units of the sampling corresponding to the deserved confidence level.

Data was collected using a survey questionnaire based on the Likert scale. The Likert scale was deliberately adopted, as it gives clearer and more concise feedback compared to binary questions, which give only two-answer options (Survey Monkey, 2024).

3.1 Validity test

The instrument (questionnaire) used in conducting this study was subjected to content validation by quantitative research experts. Therefore, a Content Validity Index (CVI) was calculated, and items were modified based on the recommendations of the experts before the final draft of the questionnaire.

3.1.1 Data analysis method

In this research, data is presented using both tables and diagrams. Simple, complex and compound-complex frequency distribution tables are used. Furthermore, pie charts and simple bar charts are equally used to present demographic data. The Chi-square method was also employed to test the relationship between variables using inferential statistics. Thus, the formula is given below:

Where:

X² = Chi-square calculated

∑ = Sigma notation, which is called summation, i.e., the sum of

O = Observe frequency from field survey

E = Expected frequency, which is the average of observed frequencies.

Thus, the Chi-square calculated is compared with the Chi-square critical table value at (n-1) degree of freedom and 0.05 level of significance. Hence, if the calculated X² is greater than the X² critical value, X² is significant and as such, the null hypothesis is rejected and the alternate hypothesis is accepted; however, if the calculated X² is less than the X² critical value, the null hypothesis is accepted.

3.1.2 Reliability test

Scale: All variables

Table 1: Case processing summary

| N | % | ||

| Cases | Valid | 373 | 93.3 |

| Excluded* | 27 | 6.8 | |

| Total | 400 | 100 |

* Listwise deletion based on all variables in the procedure.

Reliability Statistics

| Cronbach’s Alpha | N of Items |

| 729 | 20 |

3.1.3 Research hypotheses

In statistical hypothesis testing, two hypotheses, null and alternative, are usually compared. On the one hand, the null hypothesis entails a lack of relationship between a phenomenon whose relation is being investigated; on the other hand, the alternative hypothesis is the alternative to the null hypothesis (Altman, 1991). Therefore, to help answer the research question and determine whether the conflict between the Fulani herdsmen and farmers has an impact on the socio-economic development of southern Kaduna, the following null hypothesis is proposed to test the degree of relationship between the research variables:

Ho1 There is no significant effect of farmer–Fulani herdsmen’s conflict on the socio-economic development of southern Kaduna.

4. Conceptual clarifications

4.1 Cattle-herding system in Nigeria

The Fulani people, also referred to as Fula or Fulbe (the latter being an Anglicisation of the word in their language, Fulɓe), are an ethnic group spread over many countries, predominantly in West Africa but also found in Central Africa and Sudan. A good number of Fulanis also reside in Mauritania, Senegal, Guinea, The Gambia, Mali, Nigeria, Sierra Leone and other parts of Africa (Anter, 2011). The Fulani are traditionally pastoralists who rely primarily on the land and water resources to feed their cattle (Dosu, 2011). In the past, they based most of their activities in West Africa without significant problems and interference. The semi-arid conditions of the Sahel discouraged crop farming, thereby minimising possible competition between farmers and herders in the area. During dry seasons, herdsmen would temporarily move to the south to wait for the situation in the Sahel to improve before they go back to their original inhabitants (Driel, 1999).

In Nigeria, the majority of the Fulani herdsmen are located in the north-west, north-east and some states in the north-central regions of the country. However, due to desertification and scarcity of green pastures in these regions, the herdsmen are forced to move across the country in search of grazing lands and this has been the practice for decades. The movement pattern of the Fulani herdsmen varies and is sometimes dependent on the weather or individual situations. The herding among the Fulani people is largely a family business based on shared responsibility, especially among males (Akende and Cinjel, 2015). In some instances, cattle are also contracted to trusted specialist herdsmen, with compensation being in the form of a cow or the cash equivalent, depending on the contract period (Aliyu, 2015). The Meyetti Allah Cattle Breeders Association of Nigeria (MACBAN) is the national umbrella body that protects the interests of Fulani herdsmen in Nigeria and has been outspoken and controversial on issues affecting its members (Johnson, 2000).

However, southern Kaduna is a predominant agrarian and Christian community with fertile land and weather favourable for both farming and grazing. During the dry seasons, pastoralists from the far north come to the region to graze, often leading to encroachment on farmlands and triggering violent clashes with local farmers. Although the Nigerian Fulani herdsmen are arguably considered peaceful and friendly, nonetheless, the influx of Fulani herdsmen from neighbouring countries in recent years, who, unlike their Nigerian counterparts, are often armed and violent and clash with native farmers (Okoye, 1998). This situation created an incentive that implicates Nigerian Fulani in the spree of attacks and counterattacks between herders and farmers in Nigeria.

The Fulanis practice a herding system for economic and cultural purposes, known as pastoralism, involving herding livestock to find greener pastures. Traditional nomads follow irregular movement patterns, unlike transhumance, where seasonal pastures are fixed. However, this distinction is often blurred, and the term ‘nomad’ is used for both in historical cases. The regularity of movements is usually unknown (Blench, 2001). Herded livestock include cattle, sheep, goats, reindeer, horses, donkeys, camels or combinations. Nomadic pastoralism is common in regions with limited arable land, especially in the steppe lands north of Eurasia. Of the estimated 30–40 million nomadic pastoralists worldwide, most are in central Asia and the Sahel region of West Africa. However, land enclosure, fencing, overgrazing, mining, agricultural reclamation, tectonic activity and climate change have reduced land availability. There is also uncertainty about the long-term impact of human behaviour on grasslands compared to non-biotic factors (Stiling, 1999).

4.2 The concept of socio-economic development

Generally, development is defined as a state in which things are improving. But it is defined in different ways in various contexts — social, political, biological, science and technology, language and literature. In the socio-economic context, development means the improvement of people’s lifestyles through improved education, incomes, skills development and employment. It is the process of economic and social transformation based on cultural and environmental factors (Barder, 2012; Sen et al., 2016).

Socio-economic development, therefore, is the process of social and economic development in a society. It is measured with indicators, such as gross domestic product (GDP), life expectancy, well-being, living conditions, happiness, literacy and levels of employment. All these indicators are sometimes also coined as human development (UNDP, 2010; Miladinov, 2020). However, some scholars like Piketty (2009) argue that these indicators can be problematic and unique to different geographical realities. For instance, a composite index of economic development such as GDP, if not well-formulated, may lead to overly simplistic conclusions and may be misused to suit a particular policy of interest (Piketty, 2009). Nonetheless, GDP helps ascertain how well a country’s economy performs in a particular year. Due to the interlinkage between agricultural production and the social and economic well-being of southern Kaduna residents, per capita income and GDP are essential indicators for this study, particularly given the impact of the conflict on agricultural activities in the region. For a better understanding of socio-economic development, we may understand the meaning of social and economic development separately. Social development entails a process that results in the transformation of social institutions in a manner that improves the capacity of a society to fulfil its aspirations, including a qualitative change in how the society shapes itself and carries out its activities, such as through more progressive attitudes and behaviour of the population (Jacobs and Asokan, 1999). Economic development connotes the process by which a nation improves the economic, political and social well-being of its people. This concept is often used interchangeably to mean economic growth. However, the concepts, though closely related, mean different things. The first refers to the increase (or growth) of a specific measure such as real national income, GDP, or per capita income (Roser, 2021), while the latter implies much more. It is the process by which a nation improves the economic, political and social well-being of its people.

The major component of socio-economic development relevant to this study is agricultural development, which is a prerequisite for economic growth in many countries. Agriculture is important for producing food for human consumption, forage for animals, raw materials for the non-agricultural sector, employment opportunities for rural populations and improving the overall standard of living (FAO, 2017). Agriculture is also the economic mainstay of almost all the states in Nigeria. According to the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO, 2014), agriculture can contribute to economic growth by adjusting the consumption of agricultural production in proportion with the growth in internal and external demands.

Rising agricultural productivity supports and sustains industrial development in several important ways. First, it permits agriculture to release part of its labour force for industrial employment while meeting the increasing food needs of the non-agricultural sectors. Second, it raises agricultural incomes, thereby creating the rural purchasing power needed to buy new industrial goods and thus build rural savings. This may then be modified by direct or indirect means to finance industrial development (Louis, 1975).

5. Theoretical framework: Theory of frustration and conflict

Johan Galtung (1960), in his theory of frustration and conflict, opines that goals are not only set but also attained and that goal-states are reached and goals are consumed. He states that it often takes time and other resources to reach these goals, and the goal-state may, in many instances, never be attained. This is an experience of frustration, which means that access to the goal-state has been blocked. In response, the sources of frustration must be removed to permit access to the goal-state. One major source of frustration is the scarcity of resources (in this study, the scarcity of grazing lands for the Fulani herdsmen). Galtung (1960) further asserts that being unable to afford something produces a clear case of frustration; moreover, being able to afford it and discover that it is out of reach, is another frustration.

The Fulani herdsmen do not have grazing lands or ranches of any sort but rely solely on nomadic herding. With the growing scarcity of land, water and green pastures and resistance from farmers, their frustration is compounded. Worst still, all efforts to establish ranching reserves are widely opposed (ICG, 2017) due to the perceived biased handling of the conflict by the federal government in favour of the Fulani herders and insensitivity to the woes of farming communities across the country. Another dimension of frustration that fuels the clashes, as foregrounded in the introduction, is rooted in the ethnic and existing religious tensions in northern Nigeria. This is especially pronounced in southern Kaduna, where the Christian farming communities believe that attacks by the predominantly Muslim Fulani herdsmen have a sinister ulterior motive of religious conquest and land grabbing. This situation often triggers the recurring violent clashes between herders and farmers prevalent in Nigeria today.

Galtung further introduces not only one value dimension but two, so that there are two different goal-states, G1 and G2, to refer to (by application, therefore, G1=the Fulani herdsmen and G2=farmers). Beyond scarce resources as an important source of frustration, another scenario is when two goal-states abhor each other because they are incompatible. This is not the case of having insufficient resources to obtain one’s goal but of realising that one goal stands in the way of realizing another goal (here, farmers ‘stand in the way’ of the Fulani herdsmen and vice versa).

Dollard et al.’s (1939) frustration and aggression theory provides another lens through which the clashes can be understood. The frustration-aggression theory suggests that aggressive behaviour (conflict) is always triggered by frustration (1939). When applied in the context of the farmer–Fulani clashes, it infers that the resistance by farmers to allow Fulani herdsmen to graze on farmers’ farmlands and the latter’s insistence (through force or violence) to do so breeds frustration, which ultimately results in aggression. Dollard et al. further posit that frustration is not a product of emotion but an interference with the occurrence of an induced goal-response. Thus, it could be argued that the persistent clashes between Fulani herdsmen and farmers occur due to interference with each other’s goals and the response to this interference. In this case, interference with the Fulani’s open grazing by farmers and the encroachment on farmlands by the Fulani herdsmen are incentives for aggression and counter-aggression. It is therefore evident that the farmer–Fulani clashes are interplays of struggle for survival that are fuelled and exacerbated by economic, religious and political interests (Dollard et al., 1939).

6. Government policies on herder–farmer conflict in Nigeria

6.1 The National Grazing Reserve (Establishment) Bill 2016

The Bill seeks to address the prevalence of conflict between farmers and Fulani herdsmen in Nigeria. However, it is interesting to note that this idea was first conceived in the mid-1960s but was never passed as a law due to successive military rule during this period and a lack of political will by civilian governments that succeeded them. Out of the 415 grazing reserves commissioned in 1965, only 141 were instituted. The remaining 275 are yet to be commissioned due to the expropriation of the land allocated and the functionality and use of the existing 141 reserves remain limited, with many facing challenges such as encroachment and inadequate infrastructure (This Day, 2021).

The main aim of the Bill is to provide for the establishment, preservation and control of a National Grazing Reserve Commission (the Grazing Commission) in Nigeria. If or when the Bill is passed into law, the Commission will have the power to acquire, hold, lease or dispose of any property, moveable or otherwise, for carrying out its function. In addition, the Commission will also have a governing council headed by a chairperson appointed by the president and confirmed by the Senate with representatives from the Federal Ministry of Agriculture, Rural Development and Water Resources, the Ministry of Health, the Ministry of Environment, Housing and Urban Development, and the National Commission for Nomadic Education. The representatives of the above-mentioned ministries will constitute the members of the Commission, headed by a director general (Vanguard News, 2016a, 2016b).

Furthermore, the lands to be subjected to the provisions of the Act to be constituted as National Grazing Reserves and Stock Routes include lands at the disposal of the Federal Government of Nigeria. Additionally, the Commission will determine whether grazing in such land should be practised. According to The Pointer newspaper (2017), failure to comply with any of the provisions in the Act would attract a fine of N50 000 or five years’ imprisonment or both. In addition, no court of law in the country shall carry out the execution of its judgement or attachment of court processes issued against the Commission in any action or suit without obtaining the prior consent of the Attorney General of the Federation. Although the Bill has not yet been passed into law, even its consideration in the National Assembly has attracted serious criticism from different parts of the country and is perceived by many Nigerians to create more harm than good. The Bill is described as “anti-people” in some quarters because it is perceived as denying a section of Nigeria’s population their land (The Pointer, 2017).

Moreover, civil society organisations, traditional rulers, politicians and religious leaders in southern Nigeria, including their governments, have pushed back against the proposed Bill, claiming that it is: an Islamisation strategy of the north; an elevation of what ought to be private commercial ventures into a government business; an attempt to please one ethnic group over more than 400 ethnic groups; and contradictory to the principle of natural justice and the federal principle. In sum, they claim that the Bill portends danger to national unity (Vanguard News, 2016a, 2016b; The Pointer, 2017; Nathaniel, 2023).

The enactment of a grazing Act has been proposed as a means for reducing tensions between herdsmen and host communities by creating established zones in different communities that will be exclusive to and readily accessible by nomadic herdsmen and their cattle. Much of the discussion on a grazing Bill has focused on the elements of a 2008 Bill sponsored by Senator Zainab Kure and further expatiated in recent public discourse. The proposal has the following provisions: One, the establishment of a National Grazing Reserve Commission; two, appropriation of lands across different zones of the country to be designated as grazing reserves and stock routes; and, three, the conservation and preservation of the national grazing reserve and stock routes for the benefit of nomadic cattle herds (Fabiyi andOtunugajun, 2016).

While the proponents of a national grazing Bill deserve some commendation for offering what appeared to be the most detailed proposal for resolving the crisis, the ideas that underpin the grazing reserve and stock route Bill are unlikely to lead to the anticipated outcome of ending the conflict between herdsmen and the communities through which they travel for five reasons. First, it does not address the root cause of the problem, such as the pressure on water and foliage resources due to a trifecta of problems, namely, the bourgeoning cattle population, the debilitating effects of climate change and the increased levels of insecurity caused by the Boko Haram insurgency. Second, since the appropriated lands will have to be proximate to water resources to ensure that the one billion gallons per day of water needs of the cows are met, communities that the lands are taken from will be cut off from critical water reserves, thereby exacerbating pressures on already strained water reserves. Third, it will necessarily take some of the most fertile and arable lands away from farming communities, since such lands also happen to be those that are most readily stocked by plants and grass that cattle forage upon. Fourth, such grazing reserves will limit cattle to a footprint that is much smaller than they currently forage, intensifying pressures on the reserves without a concerted commercially viable means for effecting the restocking of the grass and water resources along the routes. Fifth, by drawing a line between the grazing reserves and host communities, an adversarial mentality is perpetuated, worsening tensions and reducing opportunities for cooperative and constructive engagement (Fabiyi and Otunugajun, 2016; ICG, 2017, 2018).

6.2 The RUGA (cattle colony) policy and the livestock intervention programme

The cattle settlement policy was proposed by the Nigerian government in 2018 to settle cattle herders and their families in colonies with all basic amenities, including schools, hospitals, veterinary clinics and meat processing facilities. The federal government suggested that the policy would drastically reduce the incessant farmer-herder conflict, improve the quality of beef and milk production and boost investment in commercial pasture production (Udegbunam, 2019). Soon after the policy was announced, 16 north-western states signed up for it and offered lands for implementing the project. However, the southern states rejected the policy due to limited lands, perceived Islamisation or ‘Fulanisation’ sentiments and the use of public funds by then President Buhari, who is a Fulani, to fund private animal farming largely dominated by fellow Fulanis (Fasan, 2019). The lack of transparency and the contradictory nature of the policy also created distrust and deepened the suspicion of the south. For instance, while the policy suggests that participation by states will be voluntary, the federal government secretly gazetted 5 000 hectares of land in each of the 36 states without public knowledge or consultation with the state governors, who are constitutionally recognised as landowners. Following the failure of the RUGA policy, the Federal government rebranded and re-introduced the policy as the Livestock Intervention Programme to restore the old grazing routes and end the interminable conflict between Fulani herdsmen and farmers in Nigeria. Vast plots of land have already been allocated by six states where the programme is set to start, gradually expand and be implemented in other states of the federation.

7. Demographic data presentation and interpretation

7.1 Data presentation

In this section, data about the research participants is presented diagrammatically in pie charts and bar charts. Demographics such as age and LGAs are presented in a pie chart, while the occupational distribution of respondents is presented in a bar chart.

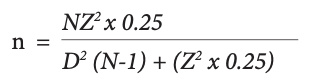

7.1.2 Age of respondents

Figure 1: Distribution of respondents by age

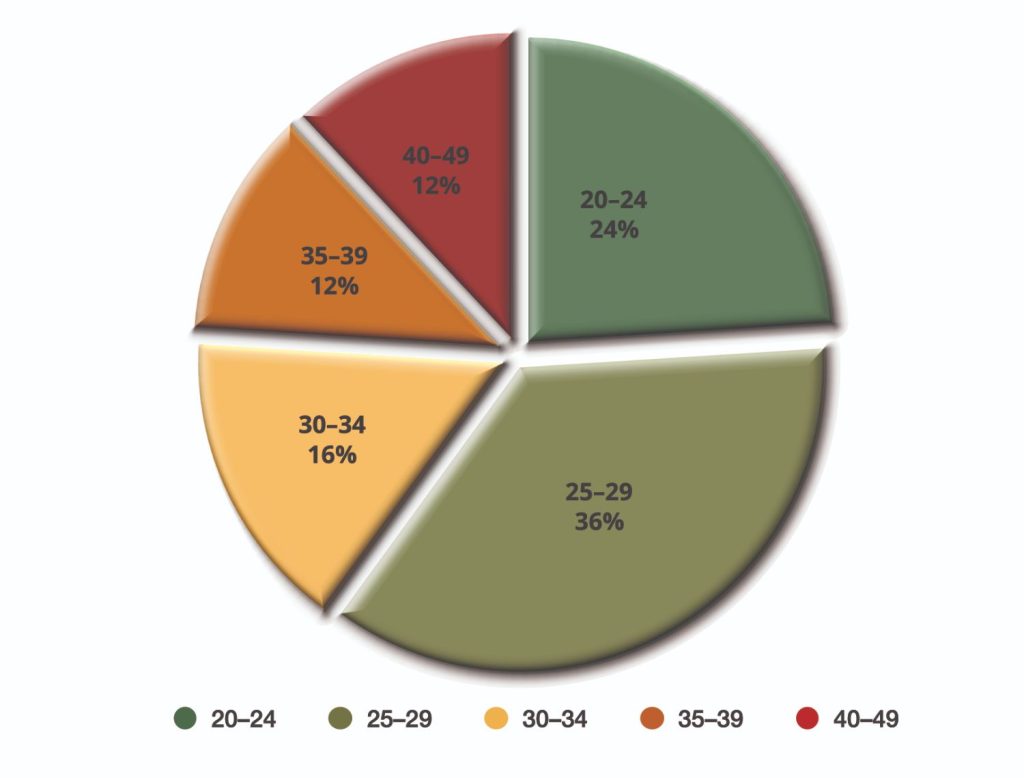

7.1.3 Local government areas (LGAs)

Figure 2: Distribution of respondents by LGAs

7.1.4 Occupation

Figure 3: Distribution of respondents by occupation

8. Test of hypothesis

8.1 Hypothesis 1

H03: There is no significant effect of the farmer–Fulani herdsmen conflict on the socio-economic development of southern Kaduna.

Table 2: Chi-square tests

| Chi-square tests | |||

| Value | df | Asymp. Sig. (2-sided) | |

| Pearson Chi-square | 40.748a | 12 | .000 |

| Likelihood ratio | 40.738 | 12 | .000 |

| Linear-by-linear association | .119 | 1 | .730 |

| N of valid cases | 1991 | ||

Table 2 shows that the Chi-square value is 40.748 with a P value of 0.000. Since the P value (0.000) is less than 0.05, the analysis concludes that there is a significant effect of the clashes on the socio-economic development of southern Kaduna.

9. Discussion of findings

The findings from the quantitative analysis provide key insights into the ongoing conflict between farmers and Fulani herdsmen in southern Kaduna. A significant proportion of respondents believe that the federal government is reluctant to take concrete measures to end the clashes, indicating a widespread perception of inaction or inefficacy by authorities. Furthermore, while about 60% of the respondents agree that security forces have been adequately deployed to curb the violence, a notable portion (38.6%) disagrees, suggesting that the security response remains inadequate. Additionally, responses regarding the concerted efforts of both federal and state governments to resolve the conflict were divided, with 36.3% strongly agreeing and 23.5% agreeing. In comparison, 39.5% disagreed or strongly disagreed, reflecting a mixed perception of governmental interventions.

The study also highlights the underlying factors fuelling the conflict. A majority of respondents attribute the violence to religious, political and ethnic motives, emphasising the multidimensional nature of the crisis. Similarly, 28.3% of respondents agree and 28.8% strongly agree that the clashes are largely a struggle for scarce land for both grazing and farming.

Further findings also reveal concerns about accountability, with 28.8% agreeing and 25.3% strongly attributing the lack of prosecution to the security forces’ lackadaisical response that allows perpetrators to go scot-free. More important to this research is the socio-economic impact of the clashes. The findings are evidenced by more than 60% of the respondents confirming that the clashes have significantly reduced agricultural output, leaving the affected communities in hunger, unemployment and a serious economic crisis. Additionally, social tensions remain high, as 45.5% strongly agree that there is serious mistrust among inhabitants, particularly between Christians and Muslims. These findings suggest that resolving the conflict will require a comprehensive approach addressing governance, security, resource distribution and intercommunal relations.

10. Conclusion and recommendations

This research examined the endemic clashes between farmers and Fulani herdsmen in southern Kaduna state and the major factors responsible for the attacks and reprisals among the two conflicting entities. To achieve this, a research survey was carried out in four LGAs of southern Kaduna in north-central Nigeria, where the conflict is rampant. Some salient questions in relation to the clashes were raised and after a thorough and rigorous examination of the incessant clashes, the study found that the clashes have had a great impact on agricultural production, the livelihood of the affected communities and more broadly, the socio-economic development of the region. These factors are further exacerbated by a lack of strong political will of successive governments at the federal level, weak policies that overlook the ethno-religious, political and economic ramifications of the clashes and, in the case of southern Kaduna, the complacency of the Kaduna state government in the response to tackling the clashes, which dents ongoing efforts and policies aimed at addressing the issue.

To this end, the study first recommends that governments at various levels should, as a matter of urgency, embark on the establishment and creation of cattle ranches to provide adequate land needed for cattle grazing in the affected areas, particularly where these conflicts are rampant. However, this must be cautiously approached, to avoid infringing or trespassing on private or individual lands, given the widespread criticism and suspicion of the ‘Islamisation’ agenda the proposed Grazing Reserve Bill received from different regions of the country. In view of this, the federal government must, therefore, engage in serious consultation with state governors and the host communities where these ranches are required for any meaningful progress to be achieved.

Furthermore, there is a need for more stringent and concrete security measures, such as community policing in collaboration with government security agencies, to help in identifying, arresting and prosecuting perpetrators and reduce the frequency and ultimately, future reoccurrence of the clashes and to ensure that the lives and properties of the affected communities are protected to create an atmosphere conducive for farming and where possible and available, ranching or grazing routes.

In addition, given the rift between the states most affected by the clashes and the federal government, particularly the past Buhari-led administration for its lax approach, the current government should take honest and genuine measures to rebuild trust and confidence in these states that hold serious grievances towards it. The federal government should do this through balanced and impartial legislation and laws on open grazing, proactive and sincere security measures and truth, justice and reparation programmes for the affected communities.

Finally, the Kaduna state government should promote and encourage sincere collaboration between and among traditional, religious and political leaders, including local community organisations, members of civil society and all the relevant stakeholders in the state. The objective of this collaboration is to bring about dialogue, reconciliation and peacebuilding in southern Kaduna to forestall and prevent the clashes from erupting into full-blown ethno-religious and political violence, as it has been widely alleged to be.

References

Abbass, I. M. (2012) No retreat no surrender: Conflict for survival between Fulani pastoralists and farmers in northern Nigeria. European Scientific Journal, 8 (1), pp. 331–346.

Adelaja, A., George, J., and Wohlgemuth, D. (2023) Stepping-up: impacts of armed conflicts on land expansion. Journal of Agricultural and Applied Economics, 55 (4), pp. 748–769.

Adeyemo, T. and Lawal, R. (2021) Governance and security challenges in Nigeria’s farmer-herder conflicts. African Security Review, 29 (3), pp. 45–46.

Akende, B. A., and Cinjel, S. A. (2015) Livelihood strategies and mobility patterns of Fulani herdsmen in northern Nigeria. Journal of African Development, 17 (2), pp. 45-58.

Akinkuotu, E. (2016) Herdsmen recorded video of Enugu massacre — Police. Punch [Internet], 26 May. Available from <https://punchng.com/herdsmen-recorded-video-enugu-massacre-police/> [Accessed 17 May 2024].

Akinwotu, E. (2016) Nigeria’s bloody clashes over land. BBC News [Internet], 17 May. Available from <https://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-36300224> [Accessed 9 December 2023].

Aliyu, M. (2015) Cattle herding and economic sustainability among the Fulani people: A case study of the North-East and North-Central Nigeria. African Journal of Agricultural Research, 10 (14), pp. 1634-1643.

Altman, D. (1991) Practical statistics for medical research. London, Chapman & Hall.

Anter, S. (2011) The Fulani people of West Africa: An overview. University of West Africa Press.

Audu, S. D. (2013) Conflicts among farmers and pastoralists in Northern Nigeria induced by fresh water scarcity. Developing Country Studies, 3 (12), pp. 25–33.

Awotokun, K. (2020) Conflicts and the retrogression of sustainable development: the political economy of herders-farmers’ conflicts in Nigeria. Humanities and Social Sciences Reviews, 8 (1), pp. 624–633.

Barder, O. (2012) What is development? Center for Global Development (CGD) [Internet], 16 August. Available from <https://www.cgdev.org/blog/what-development> [Accessed 22 August 2023].

Bello, A. U. (2013) Herdsmen and farmers conflicts in North-Eastern Nigeria: Causes, repercussions and resolutions. Academic Journal of Interdisciplinary Studies, 2 (5), pp. 129–139.

Blanchard, L.P. (2023) Nigeria: key issues and U.S. Policy. Congressional Research Service (CRS) [Internet], 9 November. Available from <https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/R/R47052/> [Accessed 15 February 2024].

Blench, R. (2001) “You can’t go home again”: pastoralism in the new millennium. London, Overseas Development Institute.

Brottem, L. (2021) The growing complexity of farmer-herder conflict in West and Central Africa. Africa Security Brief No. 39. Africa Center for Strategic Studies.

Christian Association of Nigeria (CAN). (2018) Nigerian church protest killing of Christians. CAN [Internet], 30 April. Available from <https://canng.org/news-and-events/news/173-nigerian-church-protest-killing-of-christians> [Accessed 17 May 2024].

Damba, A. (2007) The Impact of Conflict and Displacement on Economic Activities in Nigeria. Institute for Conflict Studies and Management.

Dollard, J., Doob, L. W., Miller, N. E., Mowrer, O. H., and Sears, R. R. (1939) Frustration and aggression theory. Yale University Press.

Dosu, O. A. (2011) Pastoralism and development: The role of Fulani herders in the agricultural economy of West Africa. African Journal of Agricultural Research, 6 (15), pp. 3500–3508.

Driel, F. (1999) The Fulani migration patterns in the Sahel: Traditional movements and contemporary challenges. Journal of West African Studies, 12 (2), pp. 45–59.

Egbuta, U. (2018) Understanding the herder-farmer conflict in Nigeria. Conflict Trends, 3, pp. 40–48.

Emmanuel, N. (2021) Fulani herdsmen attacks and cattle colonies: Covert Islamization of Nigeria or terrorism? A historical investigation. World Journal of Innovative Research, 10 (5), pp. 75–81.

Empowering Women for Excellence Initiative (EWEI). (2019) Situational Assessment Report [Internet], November. Available from <https://www.eweing.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/EWEI-OSS-Situational-Assessment-Report-201911.pdf> [Accessed 16 March 2024].

Fabiyi, Y. L., and Otunugajun, G. A. (2016) The role of grazing reserves and stock routes in promoting sustainable livestock production in Nigeria. Nigerian Journal of Agricultural Economics, 4 (2), pp. 45–59.

Fasan, R. (2019) On the cattle colonies. Vanguard News [Internet], 3 July. Available from <https://www.vanguardngr.com/2019/07/on-the-cattle-colonies/> [Accessed 6 February 2024].

Folami, M. O. (2009) Climate change and inter-ethnic conflict between Fulani herdsmen and farmers in South-West Nigeria. Disaster and Development, 3 (1), pp. 49–65.

Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO). (2017) The future of food and agriculture: trends and challenges. Rome, FAO.

Galtung, J. (1960) Theories of conflict and peacebuilding. International Social Science Journal, 12 (3), pp. 52–70.

Global Terrorism Index. (2015) Measuring and understanding the impact of terrorism. Institute for Economics and Peace. [Internet]. Available fro https://www.visionofhumanity.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/2015-Global-Terrorism-Index-Report.pdf > [Accessed 12 March 2024].

Herbert, S. and Birch, I. (2022) Cross-border pastoral mobility and cross-border conflict in Africa – patterns and policy responses. Birmingham, XCEPT evidence synthesis.

Ho, P. and Azadi, H. (2010) Rangeland degradation in North China: perceptions of pastoralists. Environmental Research, 110 (3), pp. 302–307.

Hoffmann, L. (2023) Violence in southern Kaduna threatens to undermine Nigeria’s democratic stability. Chatham House[Internet], 10 May. Available from <https://www.chathamhouse.org/2017/02/violence-southern-kaduna-threatens-undermine-nigerias-democratic-stability> [Accessed 20 May 2024].

Ibrahim, H. and Eboh, C. (2023) Nigerian villagers missing two days after suspected nomadic herders kill 140. Reuters [Internet], 27 December. Available from <https://www.reuters.com/world/africa/nigerian-villagers-missing-two-days-after-suspected-nomadic-herders-kill-140-2023-12-26/> [Accessed 30 December 2024].

Ijoko, A., Abubakar, A., Musa, I., and Okafor, C. (2023) Impact of herder-farmer conflicts

on food security in FCT, Nigeria. African Journal of Environmental Change (AJEC), 4 (1), pp. 22–35.

Ikyernum, S. (2023) Perspective on inter-religious crisis: Fulani herdsmen in Nigeria as a case study. Journal of African Society for the Study of Sociology and Ethics of Religions, 9 and 10, pp. 129–170.

Imobighe, T. A. (2021) Religion and conflict in Nigeria: Implications for national security. Ibadan: Spectrum Books.

International Crisis Group (ICG). (2017) Herders against farmers: Nigeria’s expanding deadly conflict. ICG [Internet]. Available from <https://www.crisisgroup.org/africa/west-africa/nigeria/252-herders-against-farmers-nigerias-expanding-deadly-conflict> [Accessed 8 May 2024].

International Crisis Group (ICG). (2018) Stopping Nigeria’s spiralling farmer-herder violence. ICG [Internet]. Available from <https://www.crisisgroup.org/africa/west-africa/nigeria/262-stopping-nigerias-spiralling-farmer-herder-violence> [Accessed 8 February 2024].

International Crisis Group (ICG). (2020) Violence in Nigeria’s North West: rolling back the mayhem. ICG [Internet], 18 May. Available from <https://www.crisisgroup.org/africa/west-africa/nigeria/288-violence-nigerias-north-west-rolling-back-mayhem> [Accessed 23 January 2024].

IRIN. (2010) Nigeria: Ethno-religious conflict in central Nigeria. IRIN News [Internet], 19 August. Available from <https://www.thenewhumanitarian.org/report/90246/nigeria-ethno-religious-conflict-central-nigeria> [Accessed 8 February 2024].

Jacobs, G. and Asokan, N. (1999) Towards a comprehensive theory of social development. Human Choice in: Cleveland, H., Jacobs, G., Macfarlane, R., and van Harten, R. ed. The Genetic Code for Social Development. Minneapolis: World Academy of Art and Science. pp. 51–152

Jaffee, D. (1998) Levels of socio-economic development theory. Bloomsbury academic.

Jinadu, L.A. (2021) Resolving the herdsmen-farmers conflicts in Nigeria. Future Africa Forum [Internet], 17 March. Available from <https://forum.futureafrica.com/resolving-the-herdsmen-farmers-conflicts-in-nigeria/> [Accessed 23 January 2023].

Johnson, P. D. (2000) The role of the Meyetti Allah Cattle Breeders Association in Nigeria: Advocacy or conflict? Journal of African Politics and Society, 23 (3), pp. 105–121.

Lacher, W. (2022) How does civil war begin? The role of escalatory processes. Violence: An International Journal, 3 (2), pp. 139–161.

Lekan, D. (2023) Climate change and conflict: implications on farmers and herders crises in Nigeria. SSRN [Internet], 5 June. Available from <https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=4315926> [Accessed 13 December 2023].

Louis, P. (1975) Agriculture and industrial development: A dynamic relationship. Oxford University Press.

McGregor, A. (2014) Alleged connection between Boko Haram and Nigeria’s Fulani herdsmen could spark a Nigerian civil war. Terrorism Monitor, 12 (10), 8–11.

Miladinov, G. (2020) Socioeconomic development and life expectancy relationship: evidence from the EU accession candidate countries. Genus, 76 (2).

Mikailu, N. (2016) Making sense of Nigeria’s Fulani-farmer conflict. BBC News. [Internet], 6 February. Available from <https://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa> [Accessed 14 May 2024].

Nathaniel, S. (2023) NASS members must remain alert, reject Grazing Reserve Bill — Ortom. Channels Television [Internet], 1 May. Available from <https://www.channelstv.com/2023/05/01/nass-members-must-remain-alert-reject-grazing-reserve-bill-ortom/> [Accessed 19 March 2024].

Odoh, S. I., and Chigozie, O. F. (2012) Climate change and conflict in Nigeria: A theoretical and empirical examination of the worsening incidence of conflict between Fulani herdsmen and farmers in Northern Nigeria. Arabian Journal of Business and Management Review, 2 (1), pp. 110–124.

Ofuoku, A. U., and Isife, B. I. (2009) Causes, effects and resolutions of farmers–nomadic cattle herders’ conflict in Delta State, Nigeria. International Journal of Sociology and Anthropology, 1 (2), pp. 47–54.

Ogu, M.I. (2020) Resurgent violent farmer-herder conflicts and nightmare in Nigeria. NILDS Journal of Democratic Studies, 1 (1).

Ojewale, O. (2021) Rising insecurity in northwest Nigeria: terrorism thinly disguised as banditry. Brookings [Internet], 18 February. Available from <https://www.brookings.edu/blog/africa-in-focus/2021/02/18/rising-insecurity-in-northwest-Nigeria-terrorism-thinly-disguised-as-banditry> [Accessed 20 February 2022].

Ojo, E. O. (2022) Contested grazing routes and the political economy of herder–farmer conflicts in Nigeria. African Affairs, 121 (483), 273–295.

Okeke, O. O. (2014) Fulani herdsmen and communal conflicts: Climate change as precipitator. International Journal of Environmental Sciences, 3 (5), pp. 210–219.

Okibe, H.B. (2022) Herder-farmer conflicts in South East Nigeria: assessing the dangers. Wilson Center [Internet], 3 October. Available from <https://www.wilsoncenter.org/publication/svnp-research-paper-okibe> [Accessed 12 February 2024].

Okoli, A. (2016) Enugu community decries arrest of 76 villagers after feud with Fulani herdsmen. Vanguard News [Internet], March 26. Available from <https://www.vanguardngr.com/2016/03/enugu-community-decries-arrest-76-villagers-feud-fulani-herdsmen/> [Accessed 17 May 2024].

Okoye, C. (1998) An evaluation of the 1971 mineral resource policy of Nigeria. Journal of Environmental Science, 2 (1), pp. 87–93.

Osaghae, E. (2022) Ethno-religious dimensions of farmer-herder clashes in Nigeria. Journal of Peace and Conflict Studies, 41 (1), pp. 67–84.

Piketty, T. (2009) Capital in the twenty-first century. Harvard University Press.

Raman, S. (2023) Outrage: Great Green Wall crumbling. The Architectural Review [Internet], 24 October. Available from <https://www.architectural-review.com/essays/outrage/outrage-great-greenwall#:~:text=Without%20the%20needed%20funds%2C%20there,is%20part%20of%20the%20GGW> [Accessed 20 May 2024].

Relief Web. (2018) Growing impact of the pastoral conflict. Relief Web [Internet], 4 July. Available from <https://reliefweb.int/report/nigeria/growing-impact-pastoral-conflict> [Accessed October 2024].

Roser, M. (2021) What is economic growth and why is it so important? Our World in Data [Internet], 13 May. Available from <https://ourworldindata.org/what-is-economic-growth> [Accessed 9 February 2024].

Sen, S., Bhattacharya, A. and Sen, R. (2016) International perspectives on socio-economic development in the era of globalisation. New York, IGI Global Scientific Publishing.

Shiklam, J. (2017) Southern Kaduna killings: Catholic church accuses El-Rufai of alleged bias. This Day [Internet]. Available from <https://www.thisdaylive.com/index.php/2017/04/19/southern-kaduna-killings-catholic-church-accuses-el-rufai-of-alleged-bias/> [Accessed 20 May 2024].

Stiling, P. (1999) Ecology: theories and applications. New Jersey, Prentice Hall.

Survey Monkey. (2024) What are Likert scales? Definitions, examples and tips. UK Survey Monkey [Internet]. Available from <https://uk.surveymonkey.com/mp/likert-scale/>

[Accessed 21 February 2024].

The Defense Post. (2023) Gunmen attack village, kill dozens in northwest Nigeria. The Defense Post [Internet], 19 April. Available from <https://www.thedefensepost.com/2023/04/19/gunmen-attack-village-northwest-nigeria/> [Accessed 11 November 2023].

The New Humanitarian. (2010) Inaction paves the way for more bloodshed, observers say. The New Humanitarian[Internet], 1 February. Available from <https://www.thenewhumanitarian.org/news/2010/02/01/inaction-paves-way-more-bloodshed-observers-say> [Accessed 5 July 2024]

The Pointer. (2017) Failure to comply with provisions of the Act attracts N50,000 fine or five years’ imprisonment. The Pointer Newspaper [Internet], 5 June. Available from <https://www.thepointernewsonline.com> [Accessed 24 April 2024].

This Day. (2021) National Grazing Reserve (Establishment) Bill 2016: Revisiting the History of Farmers–Herdsmen Conflict in Nigeria. This Day Newspaper [Internet], 26 March. Available from https://www.thisdaylive.com/index.php/2021/03/29/national-grazing-reserve-establishment-bill-2016-revisiting-the-history-of-farmers-herdsmen-conflict-in-nigeria/ [Accessed 15 January 2024].

Udegbunam, O. (2019) Presidency lists benefits of “Ruga settlements”. Premium Times [Internet], 30 June. Available from <https://www.premiumtimesng.com/news/headlines/338046-presidency-lists-benefits-of-ruga-settlements.html?tztc=1> [Accessed 20 December 2023].

Ugwu, C. (2023) “Why I believe Buhari is ‘complicit’ about herders attacks in Benue — Gov Ortom”. Premium Times [Internet], 24 May. Available from <https://www.premiumtimesng.com/regional/north-central/600353-why-i-believe-buhari-is-complicit-about-herders-attacks-in-benue-gov-ortom.html> [Accessed 18 January 2024].

Ugwueze, M.I., Omenma, J.T. and Okwueze, F.O. (2022) Land-related conflicts and the nature of government responses in Africa: the case of farmer-herder crises in Nigeria. Society, 59 (3), pp. 240–253.

United Nations Development Programme (UNDP). (2010) The real wealth of nations: pathways to human development. UNDP Human Development Report 2010. New York, UNDP.

Vanguard News. (2016a) The National Grazing Bill. Vanguard News [Internet], 22 April. Available from <https://www.vanguardngr.com/2016/04/the-national-grazing-bill/> [Accessed 2 January 2024].

Vanguard News. (2016b) Nigerians say “NO” to National Grazing Reserves Bill. Vanguard News [Internet], 30 April. Available from <https://www.vanguardngr.com/2016/04/nigerians-say-no-national-grazing-reserves-bill/> [Accessed 29 December 2023].