- Policy & Practice Brief

National youth councils as ‘behemoths’ for youth engagement and representation in Africa

Abstract

The interest in youth engagement and representation in Africa has gained currency in recent years. Consequently, legal, policy, and institutional frameworks have been established, with the goal of enhancing and strengthening youth engagement and representation in socio-economic and political spheres. In this context, national youth councils (NYCs) have been established as critical institutions for youth engagement and representation. Governments have increasingly relied on these structures to engage with young people. This Policy and Practice Brief (PPB) examines the roles of NYCs in supporting youth engagement and representation in Africa. In addition to exploring their roles, the brief unpacks the structure and characteristics of NYCs. More importantly, the brief explores challenges and suggests approaches to strengthen these institutions for better youth engagement and representation. Building on the COMESA Guidelines for Strengthening National Youth Councils, the brief advocates for robust legal and policy frameworks, resource mobilisation, adequate financial allocation, collaboration and peer support, as well as promoting accountability and capacity building.

We have a powerful potential in our youth, and we must have the courageto change old ideas and practices so that we may direct their power toward good ends.1

Introduction

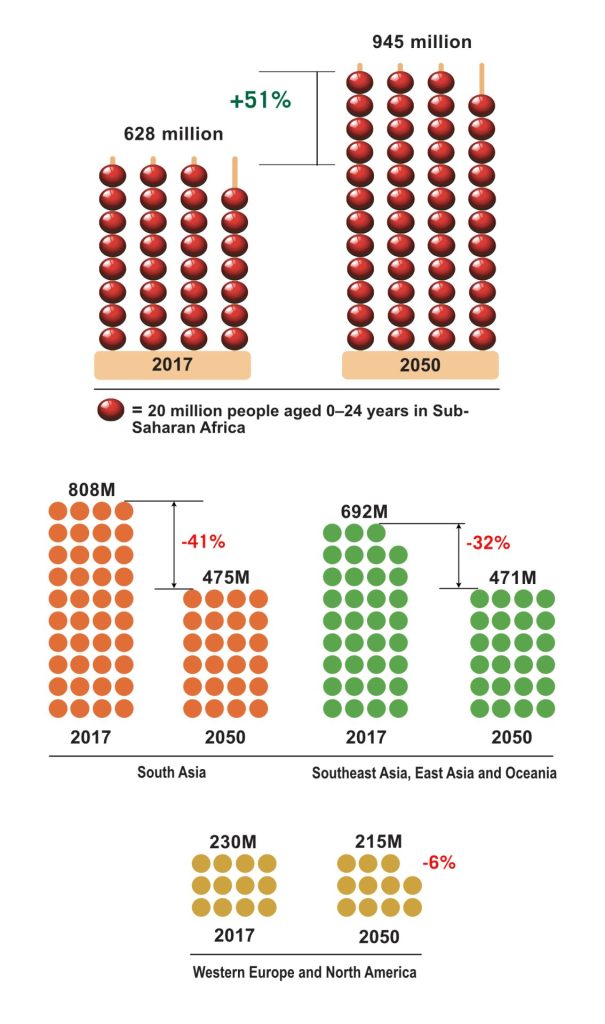

African youth make up approximately 60% of the continent’s population, and it is estimated that by 2030, they will constitute 42% of the world’s population between 15 and 25 years.2 Data compiled by the Brookings Institution in fact projects that Africa’s youth population will increase by nearly 51%, as shown in Figure 1 below.3 In 2050, the continent will have the largest number of young people – nearly twice the youth population of South Asia, Southeast Asia, East Asia, and Oceania.

Figure 1: Africa’s growing youth population.4

This youth demographic and its potential have triggered debates regarding the role of youth in socio-economic and political spheres. In essence, how can the demographic be harnessed for long-term dividends for the continent? Such questions persist as actors and stakeholders search for solutions and strategies that will guarantee youth transformation.

Despite these efforts, a cursory analysis of the youth experience in Africa paints a bleak picture characterised by uncertainty and the quest for identity and recognition. The 2024 Generation Z uprising in Kenya brings to the surface the aspirations and influence of young people. This influence has been given impetus by growth and development in the digital space. In scholarship, it has been observed that Generation Z is a ‘digital generation with high interest in social justice, governance, gradually commanding new dimensions for political engagements and activism’.5

Recognising the place and the potential of youth, legal and policy frameworks have been ratified and domesticated at national, regional, and continental levels. Institutions to facilitate youth engagement and participation have also been established. More importantly is the establishment of national youth councils (NYCs).

NYCs have emerged as structured institutions for youth engagement at the national level. Governments have increasingly relied on these structures to engage with young people. This PPB seeks to interrogate the roles of NYCs in supporting youth engagement and representation in Africa. In addition to exploring their roles, the paper unpacks the structure and characteristics of NYCs. More importantly, the challenges and ways to make them better institutions for youth engagement and representation are explored. The paper relies on secondary data sources and discussions emanating from various youth forums. This data is augmented by key informant interviews with representatives from NYCs. The paper is organised into five parts. The first part delves into the evolution of NYCs, and the second discusses legal and policy frameworks that anchor youth engagement and participation in Africa. The third and fourth sections highlight the characteristics of NYCs and the challenges they face. The last section provides recommendations for transforming and strengthening NYCs as effective institutions for youth engagement and representation.

The Evolution of NYCs

What are NYCs? The PPB understands NYCs as national structures (formally or loosely) established by national governments to champion the interests and goals of youth. In other words, they are recognised national structures deliberately created to facilitate engagement and representation. The National Youth Council report of 2006 defines NYCs as an ‘umbrella organization that facilitates the work of youth organizations nationally’.6 The European Union (EU), on the other hand, defines NYCs as:

“Youth-led, legitimate, democratically constituted bodies that are independent from governments that represent their respective Member Organisations on various levels”.7

While there is no universally agreed upon definition for NYCs, there is a common conceptual thread from the above definitions and others found in broader literature. In the context of this policy brief, a typical NYC exemplifies the following:

- Legitimate entities: The NYC should have a normative status derived from a decree, legal, or policy framework. Through this status, the government confers mandate and authority to NYCs. In essence, they are de jure endowed with the mandate to deal with the youth agenda.

- Democratically constituted: This feature denotes periodic elections for office bearers. It implies that there is a regular procedure for selecting office bearers. Consequently, office bearers carry out their mandate with the consent of the youth. This bestows legitimacy upon NYCs. However, a cursory review of NYCs on the African continent presents a bleak picture. Some NYCs have not held elections since their formation or have had disputed elections characterised by violence and state interference.

- Autonomous: NYCs should demonstrate a degree of autonomy from the government. As discussed later in this paper, this is a tall order for most NYCs on the continent. The majority of NYCs are considered appendages of the executive or the ruling party and serve as avenues for patronage.

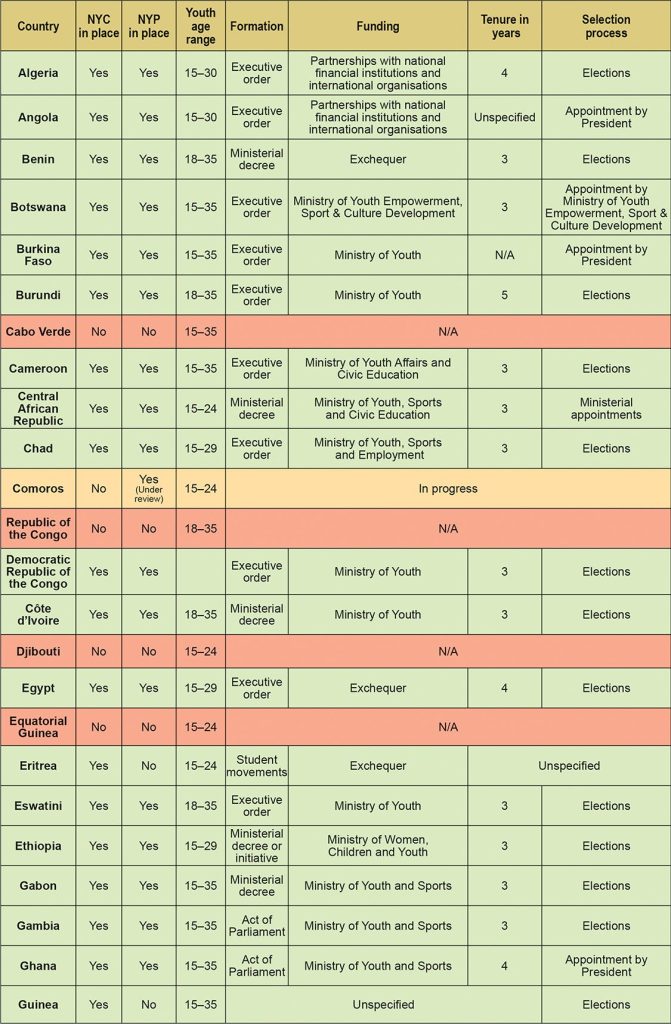

- Run and managed by young people: Each country defines ‘youth’ within its legal and policy frameworks, and there is no consistent definition, as evident from Table 1. Nevertheless, there is consensus that NYCs should be managed by young people, regardless of definitional differences.

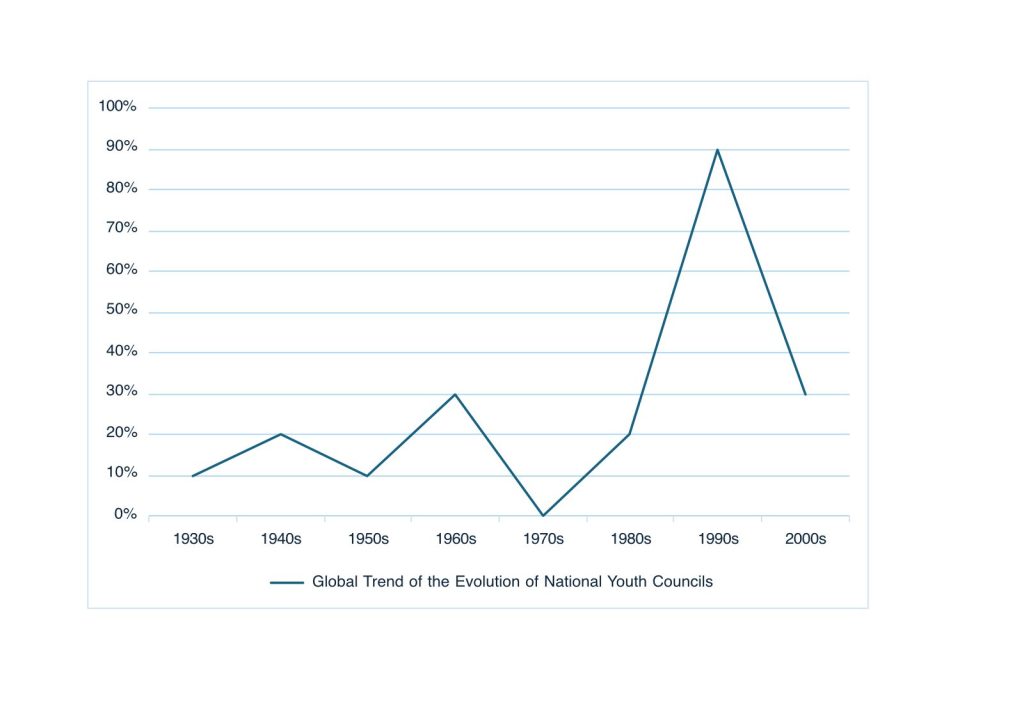

Having briefly unpacked the concept of NYCs, it is imperative to trace their evolution. The first NYCs emerged from Europe in the 1930s and 1940s, with the first recognised NYC established in 1933 in Switzerland. Many more emerged after the Second World War, including the ones set up in Sweden (1948), Germany (1949), and Belgium (1956). These councils, according to the National Youth Council report of 2006, were established to enhance and support interaction between youth in Eastern and Western Europe.8 These interactions were important for cross-cultural exchange and creating youth movements able to champion youth interests in various spheres. Since 1933, the number of NYCs has increased, with a noticeable decline in the 1970s, followed by a sharp rise in the 1990s and 2000s (see Figure 2).

Figure 2: Global growth trend in the number of NYCs9

The decline in the 1970s can be attributed to the emergence of authoritarian regimes and the shrinking of democratic space, notably in the Soviet Republic (USSR), Eastern and Western Europe, and Africa. The sharp increase in the 1990s and 2000s coincided with Samuel Huntington’s third wave of democratisation and the opening up of democratic space. According to Huntington, the third wave of democratisation was characterised by the spread of democratic values, increased education, better living standards, the expanding middle class, and a shift in domestic and foreign policies of external actors, including the European Union, the United States, and the USSR.10 We argue in this PPB that these factors permitted civil society organisations, youth movements, and youth-led organisations to emerge and flourish in various spaces. In essence, these factors ushered in a ‘new order’ globally for youth-oriented organisations.

In Africa, on the other hand, the evolution of NYCs took a different and interesting trajectory, shaped by colonialism and the youths’ quest for political participation and governance. Ideas of organised youth congregations existed as far back as 1929, when elite natives in the Gold Coast colony championed the formation of ‘a national assembly of youth to interrogate the problems that the colony was facing and to think and act together as one people’.11 Colonial rule, which subjugated most African societies and limited the freedoms and mobility of youth especially, prompted the formation of youth organisations such as the West African Youth League (WFYL) in 1934, which emerged as a political force against colonial dominance. The WFYL was succeeded by the African National Congress Youth League (ANCYL), formed in 1944 with the same objective – to challenge colonial subjugation. Many of these early organisations were loosely structured.

The struggle for independence saw African youth leading their countries as both intellectuals and ground forces. Youths were organised under the leadership of historical African political figures, such as Kwame Nkrumah and Nnamdi Azikiwe, with the aim of resisting colonial rule. In Ghana, the Committee on Youth Organisations (CYOs) aligned with the Convention People’s Party (CCP), which provided opportunities for youths to engage in crucial political decision-making processes. Other Pan-African youth organisations, such as the Pan-African Youth Movement founded in 1962, aimed to promote economic, social, and cultural development in Africa, consolidating the process of democracy in newly liberated African states and cooperating with international organisations. This later influenced continental NYCs’ emphasis on cooperating and collaborating on a regional level for the achievement of common goals. 12

In the immediate post-independence era, youth organisations and groups were heavily aligned with and reliant on independent political parties. They constituted the youth wing or league of political parties. At the time, these youth organisations were covertly tasked with defending the government of the day – an act that was equated with safeguarding hard-won independence and fostering national unity. The strong link between youth groups and government during this period gave impetus to the emergence of parallel youth groups that sought to challenge the status quo and establish a new order by creating independent youth groups that could collectively and holistically champion youth interests and ideals free from government influence. One such example is the National Union of Ghana Students, which strongly opposed the CPP government’s efforts to co-opt youth organisations. Contradiction and antagonism between different youth structures at the time pushed governments to formalise youth engagement, resulting in the formation of youth councils on the continent.

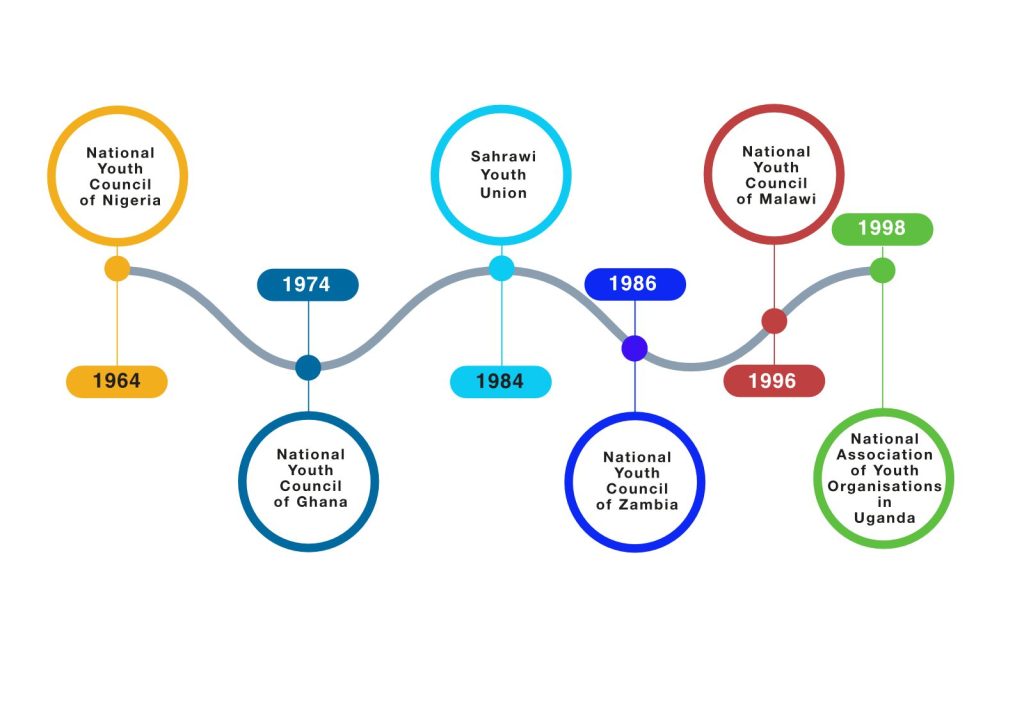

The first NYCs in Africa were formed in Nigeria (1964), Ghana (1974), the Sahrawi Arab Democratic the Republic (1984), Zambia (1986), Namibia (1990), and Uganda (1998). To date, 48 NYCs have been established on the continent, albeit with different names, depending on a country’s political context – some refer to them as councils, alliances, agencies, or unions.13 These NYCs have been established primarily to promote and ensure youth engagement, representation, and coordinated implementation of national youth programmes.

Figure 3: The first NYCs to be established in Africa

As noted above, the third wave of democratisation that swept the continent in the 1990s heralded a new dawn in the way NYCs were formed and structured. The opening up of democratic space in the 1990s resulted in the demise of youth organisations aligned with the ruling regimes and the formal establishment by governments of NYCs that exhibited, to some degree, independence and autonomy from specific political party alignment and state control. The post-2000 era saw NYC issues elevated into both continental and regional normative frameworks. This is discussed in the next section.

Normative frameworks to support NYCs in Africa

Since the establishment of the Organisation of African Unity (OAU) in 1963 and its transition to the African Union (AU) in 2002, the continent has progressively expanded its legal and policy frameworks to engage the youth. The frameworks aim to strengthen youth engagement – in this case, through NYCs. In 2006, the AU reinforced its commitment to the youth by adopting the African Youth Charter (AYC),14 which obligates NYCs to implement programmes and initiatives geared towards addressing structural inequalities. Thus, the AYC provides a blueprint for NYCs to empower, develop, and protect the rights, duties, and freedoms of young people in Africa, and provide guidance for youth development programmes at national levels. To further support NYCs in implementing the AYC, the AU published the African Youth Decade Plan of Action (2009–2018) in 2011. 15 The Plan of Action aims to ensure more coordinated and concerted efforts for accelerating youth empowerment and development. In this context, it sought to support the development of National Action Plans (NAPs), while providing a framework that allows coordinated activities among NYCs, and between NYCs, the AU, Regional Economic Communities (RECs) and other actors. Furthermore, the plan emphasises education, employment, and the institutionalisation of NYCs. While this initiative has influenced and informed the activities of NYCs at the national level, implementation and enforcement remain a challenge, not only nationally, but also at regional and continental levels.

To further support the initiatives of NYCs, several RECs – including the Common Market for Eastern and Southern Africa (COMESA), the East African Community (EAC), the Intergovernmental Authority on Development (IGAD), the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS), and the Southern African Development Community (SADC) – have developed and adopted frameworks aimed at supporting NYC empowerment and engagement in decision-making processes within their spheres of influence. These frameworks are designed to institutionalise NYCs, support youth-led governance initiatives, and advocate for youth inclusion in policymaking at both regional and national levels. For example, ECOWAS adopted the Youth Policy and Strategic Plan of Action in 2008. It is one of the most structured regional youth frameworks and is aligned with the provisions of the AYC, aiming to empower NYCs and promote the participation of young people in all spheres of life. 16 Complementing this policy is the Strategic Plan of Action, which translates the policy into programmes, projects, and activities implemented in collaboration with NYCs.

Similarly, in 2015, SADC adopted the Declaration on Youth Development and Empowerment, which provides guidelines to NYCs on integrating youth-related issues into governance, regional development programmes, and policy formulation to ensure youth are educated, economically empowered, and engaged at the political level.17 This reinforces SADC Members States’ commitment to aligning their NYC structures and youth programmes with regional and continental priorities. Additionally, to operationalise the Youth Peace and Security (YPS) agenda, the SADC convened a validation workshop on their regional strategy, which prioritises actions to address the challenges youth experience in conflict situations, while ensuring their representation and meaningful participation in peacebuilding processes. 18

The EAC, on the other hand, adopted a Youth Policy in 2013, providing a strategic framework for the administration of NYCs, as well as the implementation, monitoring, and evaluation of youth programmes and projects. This enables the empowerment of youth and facilitates their participation and benefit from regional economic, social, and political integration. Over the years, the EAC Secretariat has continued to implement this strategic framework.

COMESA adopted a Youth Policy in 2015, which is uniquely designed to integrate youth engagement and representation within its broader trade and economic integration agenda.19 The COMESA Youth Advisory Panel (COMYAP) was subsequently established as an interlocutor between NYCs, youth, and the Council of Ministers. COMESA has directly engaged NYCs through targeted training aimed at strengthening their capacities and creating a forum for cross-learning among NYCs in the region. 20

Finally, IGAD’s youth policy, adopted in 2023 aims to address numerous challenges facing youth in the region, including poverty, violent extremism, climate change, and inadequate education. Recognising youth as key to socio-economic and political progress in the region, the policy was developed to provide a structured approach to mainstreaming youth issues into national development strategies. 21 Across the continent, various NYCs refer to and are guided by these continental and regional legal and policy frameworks. In other words, they have informed the way NYCs are structured and function in different national contexts.

Characteristics of NYCs in Africa

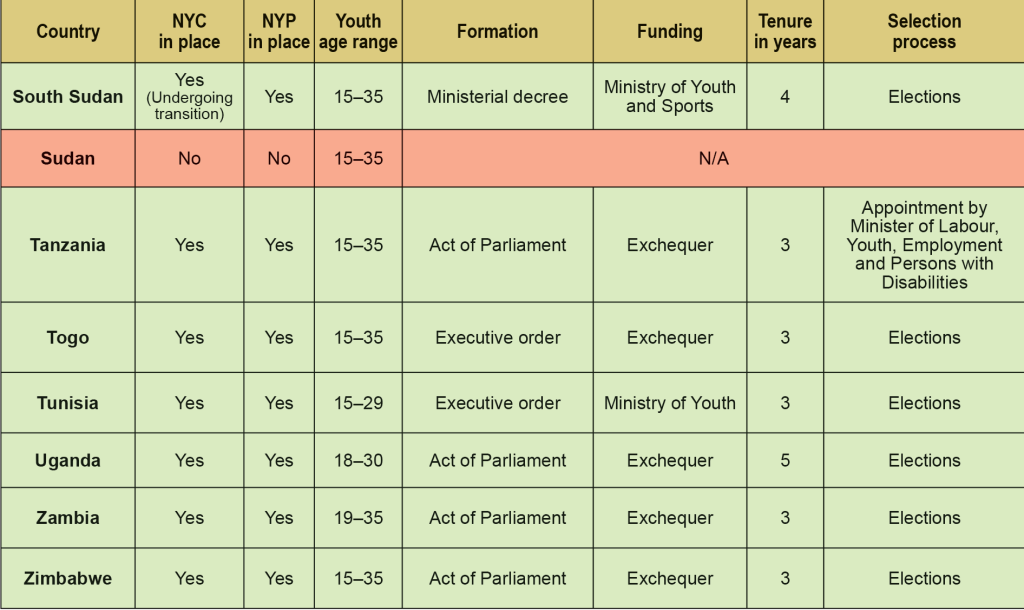

NYCs across Africa share several unique characteristics, while at the same time exhibiting country-specific variations in terms of structure, age composition, and mandate. Typically, an NYC operates as a quasi-governmental, non-partisan, and non-profit organisation established to provide an umbrella structure for youth engagement 22 Table 1 provides a summary of NYCs in 55 nations on the continent, including whether there is an NYC and National Youth Policy (NYP)23 in place.

Table 1: Summary of the characteristics of NYCs in Africa 24

Source: Compiled by the authors

Age definition and eligibility

The membership of NYCs is guided by a defined age range, although this varies from one country to another. While the AYC defines youth as individuals between the ages of 15 and 35 years, a review of NYCs across Africa reveals that youth age ranges differ widely by country. There is no universally accepted definition or statistical convention of youth. For example, Nigeria’s National Youth Policy (2019–2023) defines youths as persons aged 15 to 29 years.25 On the other hand, the NYP of Malawi defines a youth as a person within the age bracket of 14 to 40 years.26 This is different from Burundi, where a youth is construed as any person within the age bracket of 18 to 35 years.27 This variation may be attributed to social and cultural factors within each country, such as differing social independence, roles, responsibilities, and status, which likely contribute to the discrepancy. The unclear definition of youth age affects the functions and roles of NYCs and may restrict youth engagement and participation in socio-economic and political spheres.

Constitutional and legislative backing

It is evident from Table 1 that most NYCs in Africa derive their mandate from legal frameworks, ranging from constitutional provisions to specific acts of parliament and decrees. Many African countries have embedded youth development principles in their constitutions, providing a foundational legal basis for youth-focused institutions. However, while legal and policy frameworks exist, the legal status of NYCs varies across the continent. Some enjoy formal statutory recognition, whereas others operate with less clearly defined legal mandates. These legal frameworks outline the structure, mandate, guiding principles, and composition of NYCs. For example, the Zimbabwe NYC was established through the Zimbabwe Youth and Sports and Recreation Councils Act,28 Chapter 25(19). The Zimbabwe NYC, according to the Act, is authorised to perform different functions, including coordinating and supervising the activities of youth associations and clubs, participating in and advising the government on youth-related activities and needs, and undertaking youth-related projects aimed at enhancing employment opportunities for youths, among others. On the other hand, Zambia’s National Youth Development Council was established by an Act of Parliament (No. 7 of 1986), mandating it to advise, coordinate, and evaluate the implementation of youth programmes in Zambia. South Africa’s National Youth Development Agency Act of 2008 mandates the Commission to develop and implement an Integrated Youth Development Strategy (IYDS).29 Elsewhere, NYCs are established by presidential decree, such as Cameroon’s NYC, which was formed in 2009.30

Organisational and governance structure

A cursory review of legal and policy frameworks reveals elaborate governance structures for NYCs. Essentially, a governance structure constitutes the set of rules, processes, and relationships that guide the operation and management of NYCs. Most African NYCs comprise members either elected or appointed according to their legal framework. Typically, they consist of a National Executive Committee (NEC) comprised of a chairperson, vice chairperson, and members. Uganda’s NYC exemplifies this with a formal statutory governance system consisting of a five-tier hierarchical representation from the grassroots to the national level. The Council features a National Youth Executive Committee that includes a Chairperson, Vice Chairperson, and specialised secretaries responsible for departments such as women and youth, legal, financial, external relations, sports and culture, and student affairs, acting as the main policymaking body.31 Nigeria’s NEC includes 23 members led by a president, who is supported by 37 state chairpersons and local government coordinators.

From these examples, it is evident that NYCs are structured and governed differently. The bottom line, however, is that the governance structures are aimed at ensuring that youth voices from diverse geographical and demographic segments contribute to the council’s positions and priorities. For example, the National Youth Council of Nigeria (NYCN), established in 1964 but only legally recognised in 1990, demonstrates the often lengthy process of institutional formalisation. In Uganda, on the other hand, the NYC, from the outset, was established explicitly through an Act of Parliament.

Established relations with government institutions

A distinctive feature of African NYCs is their close, sometimes ambivalent, relationship with governments. While maintaining independence, they have established formal links with relevant government ministries or departments. Kenya’s NYC exemplifies this; established by Parliament in 2009 through the National Youth Council Act No. 10 of 2009, it serves as ‘a voice and bridge’ between youth and policymakers while preserving its representative character.32 In line with its Act No. 10, Kenya’s NYC preserves autonomy through its corporate status, while benefiting from formal relationships with the Ministry of Youth Affairs. Its hybrid composition, blending government representatives and elected youth members, facilitates dialogue while preserving youth-led governance. This balanced approach enables influence on national policy while maintaining credibility with youth constituencies, mirroring the successful adoption of continental and regional frameworks for youth participation.

Policy advocacy and political engagement

NYCs in Africa primarily function as policy intermediaries, linking youth constituencies with government structures. They serve as critical vehicles for youth political participation and policy influence, addressing historical patterns of youth marginalisation in governance processes. This involves policy formulation and implementation on issues affecting youth development. Councils engage in consultative processes to aggregate youth perspectives on national policy matters, distil these into policy positions, and advocate for their integration into government policies and national programmes. Uganda’s NYC is a notable example of this.33 In policy advocacy, councils employ various strategies to influence decision-making processes. These include direct participation through town halls and consultations with policymakers. Additionally, they influence decisions through surveys and research, including awareness raising through media engagement, lobbying, and civic education to drive positive political change.

Recent trends show rising youth engagement in African and global politics, facilitated by NYCs through social media mobilisation, grassroots involvement, and participation in regional platforms supported by regional organisations such as COMESA. COMESA sets the stage for other RECs by actively engaging NYCs through regional discourse platforms and capacity-building programs. It has trained over 18 NYCs regionally on socio-economic, governance, peace, and security issues.

Mandate and programme implementation

NYCs operationalise their mandates through programmes such as empowerment initiatives, sustainable development, and support schemes addressing challenges in education, employment, and civic engagement.34 The effectiveness of this function varies significantly across the continent, depending on the council’s capacity, resources, and the political openness of governance systems to youth input. NYCs in countries like Burundi and Eswatini are directly supervised by their Ministries of Youth Affairs. The NYC of Malawi is funded by the National Exchequer and reports to the Ministry of Finance on budgetary matters.35 To fill the financing gaps, the NYC also makes financial requisitions to the private sectors and non-state actors, including the UN Population Fund (UNFPA), UN International Children’s Emergency Fund (UNICEF), Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) (German Corporation for International Cooperation), and Alliance for a Green Revolution in Africa (AGRA). 36 This is predominantly the same route taken by other NYCs in Africa.

Challenges confronting NYCs

Despite their role in structuring, aggregating, and championing youth interests, NYCs across Africa face challenges that limit their effectiveness. Resource constraints are perhaps the most pervasive challenge, with many councils struggling with a shortage of financial and human resources.37 This resource deficit undermines their capacity to maintain operational continuity, implement programmes, and engage effectively in policy processes. The resource challenge is often compounded by the lack of sustainable funding models, with many councils dependent on erratic government allocations or project-based donor funding that compromises their long-term planning and institutional development.

Capacity deficits present another significant challenge, with many councils exhibiting poor lobbying and advocacy skills. This shortcoming limits their ability to effectively articulate youth interests in policy forums, negotiate with government institutions, and influence decision-making processes. The AYC has recognised this challenge, noting that NYCs require capacitation to become effective youth coordinating institutions and anchor youth development within member states.38 The skills deficit is particularly acute in specialised areas like policy analysis, strategic planning, and monitoring and evaluation, which are essential for evidence-based advocacy.

Political constraints further complicate the functioning of NYCs, with many facing a lack of political space for participation. This manifests in limited access to decision-making forums, marginalisation in policy processes and, in some cases, political co-option that compromises council independence. The 2019 Mo Ibrahim Forum Report indicated that approximately 60% of Africans, particularly youth, believe their governments are performing poorly in addressing young people’s needs.39 This perception underscores the challenges councils face in effectively translating youth concerns into policy responses. In a similar vein, the vast majority of African youth agendas do not demonstrate meaningful participation of young people in political and decision-making processes and spaces. They are often brought to the table, but only to ‘tick the boxes’. In the national contexts of some African countries, young parliamentarians, whether appointed or elected, are merely taking these seats to account for the representation of young people in the country, without any relevant opportunity to represent the youth constituency during decision-making processes. This is the case for other positions and is an unfortunate reality that needs to be addressed.

Fragmentation within the youth sector represents a significant operational challenge, with the lack of platforms for experience sharing and exchange of best practices, as well as a lack of coordination, undermining the collective advocacy potential. This fragmentation manifests in competing youth structures, duplication of efforts, and diluted advocacy impact. In some contexts, politically aligned youth wings compete with independent youth councils, creating contested representation spaces that undermine the legitimacy of formal council structures. Moreover, there is often policy disjointedness in how frameworks are interpreted and implemented at policy and programmatic level, further creating implementation hurdles between the existing normative frameworks supporting youth councils and their practical operationalisation.

Strengthening NYCs

The youth may bring the fire, but effective structures will keep it burning bright. How then can NYCs be strengthened to execute their mandate more effectively? COMESA’s guidelines provide a broad panoramic framework for strengthening NYCs and, by extension, youth engagement and representation. The guidelines are essential in ensuring that the councils operate in a credible and representative manner, effectively serving as impactful platforms for youth engagement.

Laying the groundwork: Legal and policy foundations

Two elements contained within the COMESA Guidelines for the Establishment of Effective NYCs, namely Legislation and the Institutionalisation of National Youth Policy, work to emphasise the cruciality of establishing the legal recognition, mandate and authority of the NYC. This directly enhances its legitimacy and visibility regarding youth participation, as well as ensuring that it aligns with national youth development policies and priorities to ensure they are rooted in the grander policy frameworks. Furthermore, legislation frameworks ought to propose the conditions needed to broaden the participation of youth in order to ensure greater representation and provide for structured engagement mechanisms that bring on board all levels of governance.

Solidifying the core: Structural integrity and capacity-building

NYCs must proportionately draw membership from both grassroots and national levels of governance, including youth with disabilities, students, religious representatives, the marginalised, and minority groups. In this manner, inclusivity and equity can be achieved and NYCs can be safeguarded against discriminatory composition based on gender, ethnic background, colour, and religion, among other factors. The institution of mechanisms such as affirmative action would work to enable the participation of youths who would likely otherwise be excluded. With regards to building the capacities of youth, harmonised training manuals can be utilised to sensitise the youth on their mandate, rights, roles, and responsibilities.

Fuelling the councils: Resource mobilisation and strategic collaboration

In order to strengthen their capabilities and ensure effective operations, NYCs should develop budgets that are in line with national strategic plans and make requisitions to their respective governments for funding. Most crucially, transparent guidelines on the management and utilisation of these resources need to be put in place. Additionally, provisions that allow NYCs to generate their own financial and material resources for programme implementation ought to be provided by governments. To further maintain the momentum, NYCs should seize networking opportunities with other NYCs within their region for joint programme implementation and peer support. Mutually beneficial partnerships with continental and regional bodies, such as the AU and COMESA, would likewise aid in accessing the necessary resources, strengthening youth advocacy efforts, and providing sufficient support for capacity development.

Proving presence: Advocacy and impact

Promoting youths’ active engagement and influence in decision-making and policy spaces is essential in ensuring NYCs remain visible, with impact felt regionally, nationally, and locally. Therefore, reliance on traditional and digital media platforms, most notably social media networks, is of the utmost importance in generating goodwill, creating awareness, and increasing the visibility of NYCs and their work. This is a powerful tool to wield in the mobilisation of youth and strategic partners, all of which build public trust and legitimacy and increase advocacy power, leading to stronger NYCs with greater influence.

Result orientation: Monitoring, evaluation and learning

Measuring outcomes, pinpointing areas of improvement, and establishing learning loops are critical aspects linked to the growth and robustness of NYCs. Regular assessments of the impact of NYCs’ activities, through thorough documentation, ensure accountability is secured with all stakeholders involved, such as line ministries and the youth at large. Annual general meetings should also be organised to present annual progress and financial reports, as a means of objectively measuring impact. In this manner, NYCs will be able to strategise and plan effectively, based on the success rate of projects, to capitalise on projects shown to yield the greatest impact.

Conclusion

NYCs are critical, large institutions for youth engagement and representation. It is clear from this PPB that their functions and operations in the context of Africa have evolved over time. While some have been efficient and effective in amplifying youth engagement and representation, others have failed in this task and have been characterised by antagonism, patronage, corruption, and infighting. Thus, there is a need to reimagine NYCs. In this context, the COMESA Guidelines offer strategic direction on how to reimagine and strengthen NYCs. Strengthening NYCs requires a multifaceted approach prioritising solid legal backing, inclusive participation, and sustainable resources, among others. By securing these factors, NYCs have the potential to evolve into influential platforms fit for meaningful youth engagement, representation, and leadership – a crucial investment needed in the shaping of future generations.

References

1 Hroncich, C. (2022) ‘Friday Feature: Mary McLeod Bethune’, Cato Institute, 15 July, Available at: https://www.cato.org/blog/friday-feature-mary-mcleod-bethune (Date accessed: 26 January 2025).

2 El Habti, H. (2022) ‘Why Africa’s youth hold the key to its development potential’, World Economic Forum, Available at: https://www.weforum.org/stories/2022/09/why-africa-youth-key-development-potential (Date accessed: 23 September 2025).

3 Sow, M. (2018) ‘Figures of the week: Africa’s growing youth population and human capital investments’, Brookings Institution, Available at: https://www.brookings.edu/articles/figures-of-the-week-africas-growing-youth-population-and-human-capital-investments

4 Ibid.

5 Githui, F.K. (2024) ‘Impact of Generation Z to the landscape of Kenya’s Politics’, KCA University, p. 2.

6 Siebert, C. K., and Seel, F. (2006) National Youth Councils: Their creation, evolution, purpose, and governance, Toronto, ON: Taking IT Global, Available at: https://www.youthpolicy.org/uploads/documents/2006_National_Youth_Councils_Report_Eng.pdf (Date accessed: 13 March 2025).

7 European Youth Forum (2023) ‘Safeguarding National Youth Councils and Guaranteeing the Stability of Youth Policy in Europe’, European Youth Forum, p. 2.

8 Siebert, C.K., and Seel, F. (2006) National Youth Councils, op.cit.

9 Ibid.

10 Huntington, S.P. (1991) The Third Wave: Democratisation in the Late Twentieth Century, Norma, OK: University of Oklahoma Press.

11 Gyampo, R. E., and Anyidoho, N. A. (2019) ‘Youth Politics in Africa’, in Thompson, W. E. (Ed.) Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Politics, Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 4–8.

12 Ibid.

13 Countries without structured National Youth Council include Cape Verde, Congo Brazzaville, Morocco, Niger, Equatorial Guinea, Sudan and Djibouti.

14 AU(2006) ‘African Youth Charter’, Available at: https://au.int/sites/default/files/treaties/7789-treaty-0033_-_african_youth_charter_e.pdf (Date accessed: 4 February 2025).

15 AU (2011) ‘African Youth Decade 2009–2018 Plan of Action: Accelerating Youth Empowerment for Sustainable Development’, Available at: https://www.sadc.int/sites/default/files/2021-08/African_Youth_Decade_Plan_of_Action_2009-2018.pdf (Date accessed: 4 February 2025).

16 ECOWASCommission (2010) ‘ECOWAS Youth Policy and Strategic Plan of Action’, Available at: https://www.ecowas.int/wp-content/uploads/2022/09/Youth-Policy.pdf (Date accessed: 6 February 2025).

17 SADC (n.d.)‘Declaration on Youth Development and Empowermentin SADC’, Available at: https://www.sadc.int/sites/default/files/2022-10/Declaration_on_Youth_Development_and_Empowerment_in_SADC-2015-English.pdf (Date accessed: 6 February 2025).

18 SADC(2024) ‘SADC convenes a regional consultation on the Youth Peace and Security Agenda’, Available at: https://www.sadc.int/latest-news/sadc-convenes-regional-consultation-youth-peace-and-security-agenda (Date accessed: 7 September 2025).

19 AU (2021) ‘National Youth Councils elect first ever COMESA Youth advisory panel’, Available at: https://au.int/fr/node/40818 (Date accessed: 7 February 2025).

20 COMESA(2021) ‘Youths elected to the COMESA Youth Panel’, Available at: https://www.comesa.int/eleven-youths-elected-to-the-comesa-youth-advisory-panel (Date accessed: 8 February 2025).

21 IGAD(2023) ‘The IGAD Youth Policy: A resilient, peaceful, and prosperous youth’, Available at: https://igad.int/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/IGAD-YOUTH-POLICY-Popular-Version.pdf (Date accessed: 6 February 2025).

22 Siebert, C.K., and Seel, F. (2006) National Youth Councils, op. cit. See the Mission statement, p. 39.

23 An NYP represents an agreed-upon general plan of action that provides broad guidelines from which programmes and services can be developed to facilitate the meaningful involvement of youth in national development efforts that will respond to their various needs.

24 The information in this table was gathered from key informant interviews and various open data sources. As such, there might be variations depending on the country context.

25 Federal Republic of Nigeria (2019) ‘National Youth Policy: Enhancing Youth Development and Participation in the context of Sustainable Development’, Available at: https://www.prb.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/Nigeria-National-Youth-Policy-2019-2023.pdf (Date accessed: 4 June 2025).

26 Status of National Youth Councils in the COMESA region (2024).

27 Ibid.

28 Consultations conducted in 2024 with the National Youth Council of Zimbabwe.

29 Government of South Africa (2008) National Youth Development Agency Act, Act No. 54 of 2008, Pretoria: Government of South Africa.

30 Conseil National de la Jeunesse du Cameroun (n.d.) ‘History of Cameroon National Youth Council’, Available at: https://www.cnjcnyc.cm/fr/foundation (Date accessed: 23 September 2025).

31 National Youth Council of Uganda (n.d.) ‘Who are we?’ Available at: https://www.nyc.go.ug/about-us (Date accessed: 13 March 2025).

32 Republic of Kenya (2014) National Youth Council Act No.10 of 2009, Revised edition, Available at:https://youth.go.ke/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/NYC-ACT-REVISED-2014-2.pdf (Date accessed:13 March 2025).

33 Ministry of Gender, Labour and Social Development (2021) ‘National Coordination Mechanism for Youth Programmes’, Available at: https://mglsd.go.ug/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/National-Youth-Coordination-Mechanism-for-Youth-Programme-Final-Printed-Copy_2.pdf (Date accessed: 12 June 2025).

34 Siebert, C.K., and Seel, F. (2006) National Youth Councils, op. cit.

35 Consultations conducted in 2024 with the National Youth Council of Malawi.

36 Ibid.

37 Gedion,G. (2014) ‘Challenges and Opportunities of Youth in Africa’, US–China Foreign Language, 12 (6), 537-542, Available at: https://www.davidpublisher.com/Public/uploads/Contribute/5518fbea0c665.pdf (Date accessed:13 March 2025).

38 AU (2006) ‘African Youth Charter’, op.cit., p. 8.

39 Luanda, M. (2020) ‘Africa’s Diverging Approaches to Youth Inclusion and Participation’, South African Institute of International Affairs, Available at: https://saiia.org.za/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/Occasional-Paper-307-mpungose.pdf (Date accessed:13 March 2025).

Authors

Oita Etyang holds a PhD in Political Science from the University of Johannesburg (RSA). Dr Etyang has over a decade of experience across Africa, covering the wider spectrum of conflict prevention, management, resolution and post-conflict reconstruction processes.

Claudia Masahhas a Master’s degree in political science and strategic studies from the University of Yaoundé 2, Cameroon. Claudia’s interest is in the area of Peace and Security across Africa. She has over five years of experience in conflict prevention with a focus on YPS.

Tatenda Mapirois is an International Development practitioner committed to advancing peace, security, and stability in Africa. With four years of experience in programme design and implementation, she focuses on conflict prevention and civil society engagement to promote peace and security across the continent.

Nouran Abadi holds an MA in Peace and Security Studies from the University of Lusaka. She is a Junior Expert at COMESA. Her work focuses on advancing youth engagement in peace and security, promoting conflict prevention, and supporting post-conflict peace building initiatives across the region.