Conflicts in Africa always results in deep-rooted divisions based on ethnic, political, religious lines, and fractured societies.1 While national dialogue is a fundamental remedy in the realisation of sustainable peace, security and stability, the process should be inclusive, nationally owned political negotiations that foster reconciliation, address grievances, and create a conducive environment for democratic leadership.2 It should bring on board all actors, including opposition groups, civil society, government, and marginalised groups, for the realisation of future social and political order.

However, the effectiveness of national dialogue in post-conflict transitions have attracted wider debate. While scholars and policy-makers have hailed national dialogues as tools for peacebuilding, their effectiveness is not guaranteed.3 Key considerations, for example, the structure of the dialogue, participants’ credibility, the extent of inclusivity, and the political will to implement agreements, are critical to their outcomes.4 In many instances, national dialogues have failed to yield tangible and sustainable results, more so when taken over by political elites or due to lack of political goodwill to implement agreements.

Sudan offers a good case study for challenges to national dialogue in post-conflict settlements. In past decades, Sudan has witnessed protracted conflicts, for example, the Civil War (1983–2005) and the conflicts in Darfur (2003 to date).5 All these have resulted in intricate political situations. The signing of the Comprehensive Peace Agreement (CPA) brought an end to the civil wars between the south and the north, eventually leading to the secession of South Sudan in 2011.6 However, peace remained elusive in the rest of the country, due, in part, to ongoing feuds in Darfur and other regions.

In 2014, President Omar al-Bashir introduced initiatives for national dialogue that marked the beginning of critical efforts by Sudan to address protracted conflicts and reshape the country’s political order.7 Despite hope emanating from the international community, the dialogue was criticised for being a top-down approach, excluding key opposition figures, and lacking the legitimacy required for meaningful change.8 Following the 2019 revolution, which resulted in the ousting of Omar al-Bashir and the formation of a transitional government, Sudan embarked on a fresh political transition marked by renewed calls for national discourse to foster peace and bring an end to the crisis in the country. However, this call was marred by political instability, notably the October 2021 coup.

This article navigates the success of these dialogues as a strategy for peacebuilding and political transition in Sudan. By focusing on national dialogues from 2014 to 2016 and post-2019 dialogue efforts, the article aims to assess whether these dialogues met the required standards of legitimacy, inclusivity, transparency and implementation. This article argues that, while dialogues serve as important tools and have the potential for post-conflict transition, their effectiveness relies solely on political goodwill, genuine inclusivity, and proper mechanisms for accountability. Mirroring this, the article provides broader insights into the setbacks and opportunities of national dialogue processes in post-conflict and fragile states.

Discussion on national dialogues

National dialogues have been employed in Africa as a tool for conflict resolution, to enhance reconciliation, and to offer a foundation for democratic transitions.9 National dialogues can be broadly understood as multi-stakeholder processes that are inclusive and aimed at addressing systemic conflict or political crises. According to Avruch, the aim of such dialogues is to renegotiate the social contract between society and government, acting as an alternative voice or offering a complement to traditional peace processes.10

In post-conflict reconstruction, national dialogues are a way of addressing: (i) root causes of conflict, including historical grievances, marginalisation, and social, economic and political exclusion among others; (ii) facilitating transitional reconciliation and justice; (iii) designing political and institutional frameworks, either through power-sharing deals or constitutional reforms; and (iv) enhancing national cohesion, integration and legitimacy for transitional governance.11

However, scholars and policy-makers warn that national dialogues can become instruments for political leaders to retain power, or to exert pressure without real implementation of reforms.12 Misusing national dialogue by political leaders in post-conflict transitions involves manipulation of the process for the consolidation of power, at the expense of genuine reconciliation and sustainable peace.13 This can include suppressing dissent, marginalising groups, or sometimes using dialogue to buy time or impress international actors without genuine commitment to political or institutional reforms.

Many African countries have used national dialogues with different outcomes, for example:

- The 2013–2014 national dialogue in Tunisia (a Nobel Peace Prize-winning case) achieved genuine inclusion and political will, leading to success through avoiding political collapse.

- The National Accord (2008) in Kenya helped in post-conflict reconstruction by forming a coalition government after the post-election violence of 2007–2008.

- While the Bangui Forum (2015) in the Central African Republic did not prevent future conflict, it fostered short-term stability.

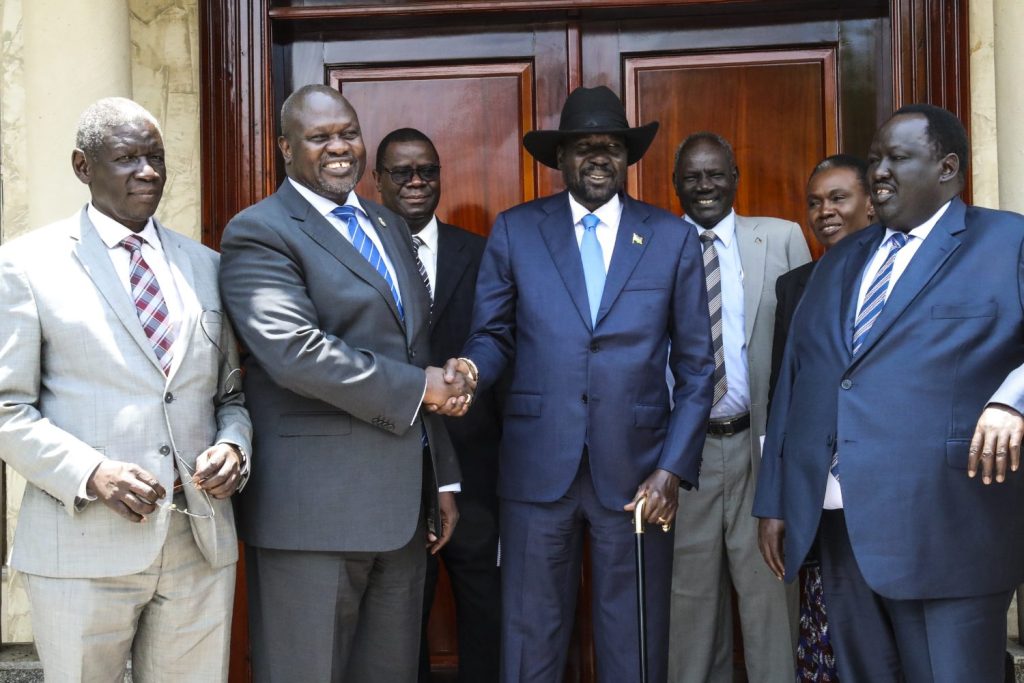

- Additional national dialogues in South Sudan and the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) have produced little success, due to the exclusion of critical actors and weak mechanisms for enforcement of outcomes.

While scholars have produced substantive research as far as national dialogues are concerned, specific gaps still exist. These gaps relate to why some national dialogues succeed while others fail in a similar context. There is also a lack of local-level studies on the community-level perceptions and impact of national dialogue and long-term impact assessments, particularly in countries like Sudan with overlapping transitions. This prompts the present research.

This study focuses on Sudan as a representative example of national dialogues in post-conflict reconstruction in African states. The following questions guide the paper: (i) What is the historical context and motivation behind national dialogue initiatives in Sudan? (ii) What is the level of inclusivity and representation in the national dialogue processes in Sudan? (iii) What are the outcomes of national dialogue processes in terms of governance reforms, conflict resolution, and national cohesion? (iv) What are the challenges and limitations that affect the effectiveness of national dialogues in Sudan?

National dialogues in Sudan

The success of national dialogues in post-conflict transitions depends on a range of factors such as the legitimacy of the process, genuine inclusivity, political goodwill to implement agreements, and transparency.14 In this part, the article draws from the case study of Sudan to examine how these issues have shaped the results of national dialogues, focusing on the national dialogue initiated by then President Omar Al-Bashir in 2014 and the initiatives for dialogue post-2019.

i. Genuine inclusivity in processes of national dialogue

Genuine inclusivity encompasses a wide range of ethnic, political, and social groups in the process of dialogue. While the 2014 and 2019 national dialogues in Sudan faced significant setbacks with regard to genuine inclusivity, the 2014 national dialogue was hailed as a major turning point in Sudan’s political history, because, major rebel groups and key opposition leaders were excluded. The Sudan People’s Liberation Movement-North (SPLM-N) and the Sudan Revolutionary Front (SRF), who were key actors in the conflict in Darfur, disassociated themselves from the national dialogue, claiming that the process lacked credibility and was under the control of the government.15 The failure to bring these two major actors on board undermined the potential for an inclusive and equal representation framework for peace.

While there was marginal improvement in 2019 and afterwards, the revolution of 2019 and the subsequent removal of al-Bashir from power created an enabling environment where civil society, the marginalised, and opposition groups could be more actively involved in the transition process. The Juba Peace Agreement (2020) signified positive progress in integrating armed groups into political activities, although the continued involvement of the military in the transitional government limited genuine inclusion of civilian forces.16 The October 2021 coup was a clear indication of a lack of genuine inclusion and resulted in significant setbacks to promoting true ownership of the process among all parties in society.

Therefore, the processes for national dialogue in Sudan clearly illustrate that, while significant attempts have been made, genuine inclusivity is necessary. To succeed, dialogue must involve key opposition leaders, unarmed opposition factions, and marginalised communities; otherwise, peace in Sudan will remain elusive.

ii. Legitimacy of the process

The success of a national dialogue depends largely on the legitimacy of the process, as it directly impacts the inputs from varied stakeholders and the wider public. The legitimacy of the national dialogue in 2014 in Sudan was criticised from the outset. It was viewed as a top-down approach managed by a government that had been in power for the past two decades. Consequently, the ruling class was accused of attempting to maintain the status quo at the expense of genuine efforts for peace.17

The withdrawal of key opposition groups from participation in the national dialogue, along with the government’s manipulation of the process, further undermined its legitimacy. Many stakeholders, including the SPLM-N and other major political actors, rejected the government’s final National Document on dialogue, perceiving it as insufficient in reflecting the diverse needs and aspirations of Sudan.18 The inability of the 2014 national dialogue to yield sustainable peace or significant political change illustrates the importance of legitimacy: a process not seen as legitimate by all parties is unlikely to deliver meaningful results.

In comparison, the national dialogue processes after 2019 benefited from a greater degree of legitimacy, particularly after the ousting of al-Bashir and the subsequent creation of a power-sharing agreement between civilian and military forces.19 However, attempts to undermine the legitimacy of the newly introduced transitional process soon emerged in the form of protests, coups, and ongoing tensions between civilian and military groups. The 2021 military takeover was a clear reminder that even post-revolutionary dialogues can quickly lose legitimacy if key power dynamics remain unresolved.

iii. Transparency in the dialogue process

Transparency plays a critical role in building trust among all parties during national dialogue processes. It also ensures accountability and genuine inclusivity.20 Transparency in both the 2014 and post-2019 national dialogues in Sudan has been contested. For instance, the 2014 national dialogue was criticised for insufficient transparency, as decisions were made behind closed doors by a small group of elites.21 The process was marred by secrecy, inadequate access to information, and a lack of genuine participation. This insufficient transparency generated scepticism about the government’s intentions, and the credibility of the dialogue was widely dismissed.22

The national dialogue in 2019 was slightly more transparent, particularly with the inclusion of international actors such as the United Nations (UN) and the African Union (AU) in mediation processes, which ensured broader participation. However, despite efforts towards greater openness, the continuous dominance of the military within the transitional government and the prevailing political instability continued to limit transparency by restricting access to information. This absence of transparency remains a major barrier to enhancing public trust and achieving genuine participation.

iv. Implementation of dialogue outcomes

National dialogues often yield certain agreements, and the implementation of these agreements is perhaps the most important aspect in assessing effectiveness. The implementation of agreements from both the 2014 and post-2019 dialogue initiatives in Sudan has been deeply disappointing.23 The 2014 dialogue produced the National Document, which proposed multiple political changes and constitutional reforms. However, due to the absence of robust implementation mechanisms – including monitoring, evaluation, and political goodwill – many reforms were not realised. The failure of the Sudanese government to translate outcomes into tangible changes further undermined the credibility of the process. This deepened cynicism over the government’s commitment to reform.

In contrast, the post-2019 national dialogue, including the Juba Peace Agreement, also faced significant setbacks in implementation. Despite some positive steps, such as the inclusion of armed groups in government, the power-sharing arrangement between civilian and military forces was fragile, leading to delays in critical provisions. The 2021 coup further exacerbated setbacks, stalling reforms and leaving Sudan in a state of political limbo.

Conclusion

Sudan offers a critical control experiment in highlighting setbacks in the design and implementation of national dialogues in post-conflict settlements. One of the main challenges is the lack of political will from leaders, who often capitalise on national dialogues as a tool for maintaining power instead of ensuring genuine reforms. Additionally, the dominance of military actors in the post-2019 national dialogue has created an environment where it is difficult to implement civilian-led reforms, thereby undermining the sustainability and legitimacy of the transition.

The lesson we can draw from Sudan’s experience is that genuine inclusivity, transparency, accountability, and political will are critical for the success of national dialogues. The design of such dialogues must include all relevant actors, including those typically excluded from formal political processes. Moreover, outcomes must be accompanied by clear frameworks for implementation and robust monitoring and evaluation mechanisms, backed by commitment to enforcement.

Recommendations

From the findings of this study, several recommendations can be made to ensure national dialogues are effective in post-conflict reconstructions:

- Future national dialogues must ensure genuine inclusivity of all relevant political parties and social actors, including marginalised groups, opposition parties, and armed groups. Inclusivity should be evident in both the design and implementation of the processes of national dialogue.

- National dialogues should not only appear, but also be seen to be legitimate. This can be realised through ensuring that the process is free from political manipulation, that all actors have an equal say, and that the outcome is a true reflection of the diverse needs of the people.

- Efforts should be made to ensure that future dialogues are transparent and accountable. Transparent and accountable processes build trust and ensure that decisions are fair. This can be achieved by guaranteeing public access to information and involving civil society in dialogue processes.

There is a need for effective monitoring and implementation of national dialogue outcomes to ensure that agreements yield tangible political and social change. International actors, for example the UN and the AU, can be critical in supporting these efforts.

Benson Nyamweno, is a Gerda-Henkel Stiftung Foundation PhD Fellow and Lecturer at the College of Humanities and Social Sciences (CHUSS), Makerere University, Uganda as well as a research fellow at the Institute for Research and Policy Integration in Africa (IRPIA), Sierra Leone.

Endnotes

1Ndekwo, R. (2020) National dialogue as a strategy for intra-state conflict resolution in Africa: the case study of Anglophone Cameroon, Doctoral dissertation, University of Nairobi.

2Mandikwaza, E. (2024) ‘A conceptual framework for national dialogues: applied theories and concepts’, African Journal on Conflict Resolution, 24(2), 7–28.

3Haider, H. (2019) ‘National dialogues: lessons learned and success factors’, Knowledge, Evidence and Learning for Development (K4D).

4Ansorg, N. and Gordon, E. (2020) ‘Co-operation, contestation and complexity in post-conflict security sector reform’, In: Ansorg, N. and Gordon, E. (Eds), Co-operation, Contestation and Complexity in Peacebuilding, London: Routledge (pp. 1–23).

5Nyadera, I. N.; Islam, M. N.; and Shihundu, F. (2024) ‘Rebel fragmentation and protracted conflicts: lessons from SPLM/A in South Sudan’, Journal of Asian and African Studies, 59(8), 2428–2448.

6Ibid.

7Ndiaye, M. (2024) ‘Collaboration between states and militias and state fragmentation: The cases of Sudan and Sierra Leone’, African Conflict and Peacebuilding Review, 14(3), 113–132.

8Verhoeven, H. (2023) ‘Surviving revolution and democratisation: the Sudan armed forces, state fragility and security competition’, The Journal of Modern African Studies, 61(3), 413–437.

9True, J. and Riveros-Morales, Y. (2019) ‘Towards inclusive peace: analysing gender-sensitive peace agreements 2000–2016’, International Political Science Review, 40(1), 23–40.

10Avruch, K. (2022) ‘Culture and conflict resolution’, The Palgrave Encyclopedia of Peace and Conflict Studies. Cham: Springer International Publishing (pp. 254–259).

11Smidt, H. M. (2020) ‘United Nations peacekeeping locally: enabling conflict resolution, reducing communal violence’ Journal of Conflict Resolution, 64(2-3), 344–372.

12Begealawuh, N. C. (2024) ‘Missed or misused opportunity? Social cohesion, national dialogue and peacebuilding in Cameroon’, African Security Review, 33(4), 497–513.

13Freeman, M., and Peña, M. C. (2023) ‘Negotiating with organized crime groups: Questions of law, policy and imagination’, International Review of the Red Cross, 105(923), 638–651.

14Deleglise, D. (2024) ‘African special envoys in practice: a research agenda for studying complex diplomatic interventions’ DEU (Vol. 3, p. 31).

15Haider, H. (2019) ‘National dialogues’, op. cit.

16Machar, B. (2015) ‘Building a culture of peace through dialogue in South Sudan’, Policy brief, Sudd Institute.

17Haider, H. (2019) ‘National dialogues’, op. cit.

18Haider, H. (2019) ‘National dialogues’, op. cit.

19Ndekwo, R. (2020) National dialogue, op. cit.

20Deleglise, D. (2024) ‘African special envoys in practice: a research agenda for studying complex diplomatic interventions’ DEU (Vol. 3, p. 31).

21Haider, H. (2019) ‘National dialogues’, op. cit.

22Sampson, C. J.; Arnold, R.; Bryan, S.; Clarke, P.; Ekins, S.; Hatswell, A.; and Wrightson, T. (2019) ‘Transparency in decision modelling: what, why, who and how?’ Pharmacoeconomics, 37(11), 1355–1369.

23Haider, H. (2019) ‘National dialogues’, op. cit.