Since the 1990s, Africa has become an epicentre of complex and evolving security challenges, ranging from intra-state conflicts, insurgencies and political instability to terrorism in the Sahel and the Horn of Africa and maritime insecurity in the Gulf of Guinea and Indian Ocean.1 These threats are not only locally rooted but are also regional in scope and intertwined with organised crimes, climate pressures, and governance deficits. The frequency and complexity of these security challenges have made it clear that Africa must not only be the subject of peace operations, but also the architect of its own security responses. Consequently, African-led peace support operations (PSOs) have emerged as a principal instrument through which the African Union (AU), Regional Economic Communities (RECs), Regional Mechanisms (RMs), and ad hoc coalitions of states have attempted to respond to the continent’s complex security challenges. Once the exclusive preserve of United Nations (UN) peace operations, the emergence of African-led PSOs was driven by both pragmatic and normative considerations – including the urgent need for context-sensitive responses, the assertion of African agency, and the growing recognition that no external actor will prioritise Africa’s peace and security more than Africans will.2 It also highlighted the operationalisation and efforts to realise the ‘African solutions to African problems’ paradigm that emphasises African ownership, leadership, and context-driven approaches to addressing the continent’s challenges.3

The African Peace and Security Architecture (APSA), established in 2002 with its various components such as the African Standby Force (ASF), serves as the institutional backbone for the expanding role of African-led peace operations.4 As a continent-wide rapid-response mechanism, the ASF is designed to provide the AU and its RECs/RMs with a ready pool of military, police, and civilian personnel for PSOs. However, since its conception, the ASF has remained only partially realised, raising critical questions about the continent’s readiness and capacity for self-reliant PSOs. The growing threat of terrorism and violent extremism and the resurgence of military coups have also magnified the need for ASF reform and adaptation to remain fit for purpose.

Against this backdrop, this article reviews the trajectory and current state of African-deployed PSOs, with a specific focus on the ASF. After a concise overview of contemporary PSOs in Africa, the article explores how the ASF has progressed in practice, while persistent gaps and barriers that have constrained its functionality. Through a forward-looking lens, the article concludes by offering future scenarios and concrete policy recommendations aimed at strengthening African agency and capacity in PSOs. The paper conceptualises African-led PSOs as missions mandated, deployed, recognised, or endorsed by African regional institutions. It argues that African-led PSOs are more agile, localised and often provide quicker responses to peace and security challenges in the region, especially in places where UN responses are absent or slow. These PSOs have been conducted by AU forces, regional organisations and ad hoc coalitions of states. The ASF is a laudable, African-led mechanism with significant efforts and investment made in the development of policies, structures and regional capabilities, but the it faces challenges in operationalisation.

Overview of contemporary African-led peace operations

African regional and sub-regional institutions have assumed increasing security roles due to the UN’s inability to respond in a timely fashion to the security challenges in Africa. Certain developments, such as the transformation from the Organisation of African Unity (OAU) into the AU in 2002 and revisions to the founding documents of RECs like the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS), have provided avenues to renewed African agency in dealing with persistent peace and security challenges on the continent.5 Notably, the Constitutive Act of the AU provided a paradigm shift from the OAU on issues surrounding sovereignty and intervention, thereby providing a normative framework for collective action and peace operations. The AU and RECs, in particular, have therefore taken it upon themselves to address peace and security challenges in Africa through peacekeeping, peace enforcement missions, PSOs, and preventive diplomacy.6 Although ECOWAS is a subsidiary of the AU, its comparative advantage in West Africa and proactive stance on conflicts, as well as its internal organisation and institutional capacity, are often ahead of similar processes within the AU. To this end, African-led peace operations have emerged as one of the critical mechanisms used by the AU and RECs to address security challenges and stabilise crisis zones. The UN Security Council (UNSC) passed the historic Resolution 2719 on 21 December 2023, which addresses the funding of PSOs directed by the AU. This Resolution presents a major funding boost to African-led peace operations despite the hurdles in its implementation.7

Africa is witnessing a new wave of regionalism where countries are now harnessing their strengths to tackle common threats. Notably, there has been the emergence of collaborative initiatives such as the G5 Sahel to foster economic cooperation and tackle threats posed by militant Islamist groups in the Sahel region. Similarly, other countries have adopted a Multi-National Joint Task Force (MNJTF) to fight Boko Haram. The Accra Initiative is the latest of such mechanisms to prevent the spread of violent extremism. These RMs have been endorsed by the AU Peace and Security Council (PSC), ECOWAS, and the UNSC, and supported by international partners. These ad hoc security initiatives have provided flexible and rapid responses to complex security threats. They are, nevertheless, highly militarised and not well-suited to the changing frameworks for the protection of civilians (POC). They frequently do not have well-developed civilian components.8

Types of African-led PSOs

There are specific variations in the nomenclature of the African-led missions. Table 1, which is adapted from the AU Peace Support Operations Division, describes the types of PSOs in Africa.

Table 1: African-led PSOs9

| Type | Description | Examples |

| AU-led PSO | PSO mandated by the AU Assembly or PSC and directly commanded, controlled, and managed by the AU. | AU Mission in Somalia (AMISOM) African-led International Support Mission to Mali (AFISMA) AU Transition Mission in Somalia (ATMIS) AU Mission in Burundi (AMIB) AU Mission in Sudan (AMIS I and II) AU Mission for Support to the Elections in the Comoros AU Military Observer Mission to the Central African Republic (AUMOC-CAR) AU Monitoring, Verification and Compliance Mission (AMCCM) |

| AU-authorised PSO | PSO authorised by the AU PSC, required to comply with AU PSC protocol and doctrine, and provided technical and material support by the AU, but not directly commanded, controlled, and managed by the AU. | AU Transition Mission in Somalia (ATMIS) AU Military Observer Mission to the Central African Republic (MOUACA) AU Monitoring, Verification and Compliance Mission (AU-MVCM) in Ethiopia’s Tigray region AU Mission in Somalia (AMISOM) AU-UN Hybrid Operation in Darfur African-led International Support Mission in Mali (AFISMA) |

| AU-endorsed PSO | PSO that is not mandated by the AU PSC, or commanded, controlled, or managed by the AU, but the AU PSC receives periodic briefings from the mandating authority or the PSO. | AU Mission in Somalia (AMISOM/ATMIS) AU-UN Hybrid Operation in Darfur (UNAMID) African-led International Support Mission in Mali (AFISMA/MISMA) AU Mission in the Central African Republic (MISCA) |

| AU-recognised PSO | PSO that is similar to an AU-endorsed PSO, with the AU PSC taking note of the decisions of the mandating authority when considering the conflict situation. | AU Mission in Somalia (AMISOM) AU-UN Hybrid Operation in Darfur (UNAMID) AU Mission for Mali and the Sahel (MISAHEL) African-led International Support Mission to the Central African Republic (AFISM-CAR)Operations supporting the Regional Strategy for Stabilisation, Recovery and Resilience in the Lake Chad Basin |

| Regional PSO | PSO deployed by RECs. | ECOWAS Monitoring Group (ECOMOG) (Liberia, Sierra Leone) ECOWAS Mission in Liberia (ECOMIL) ECOWAS Mission in Côte d’Ivoire (ECOMICI) ECOWAS Stabilisation Support mission in Guinea Bissau (ECOMIB) ECOWAS Mission in the Gambia (ECOMIG) Eastern Africa Commission intervention in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) Southern African Development Commission (SADC) Mission in Mozambique |

| Ad hoc coalitions | PSO deployed by states outside of RMs. | G5 Sahel joint force MNJTF Accra Initiative |

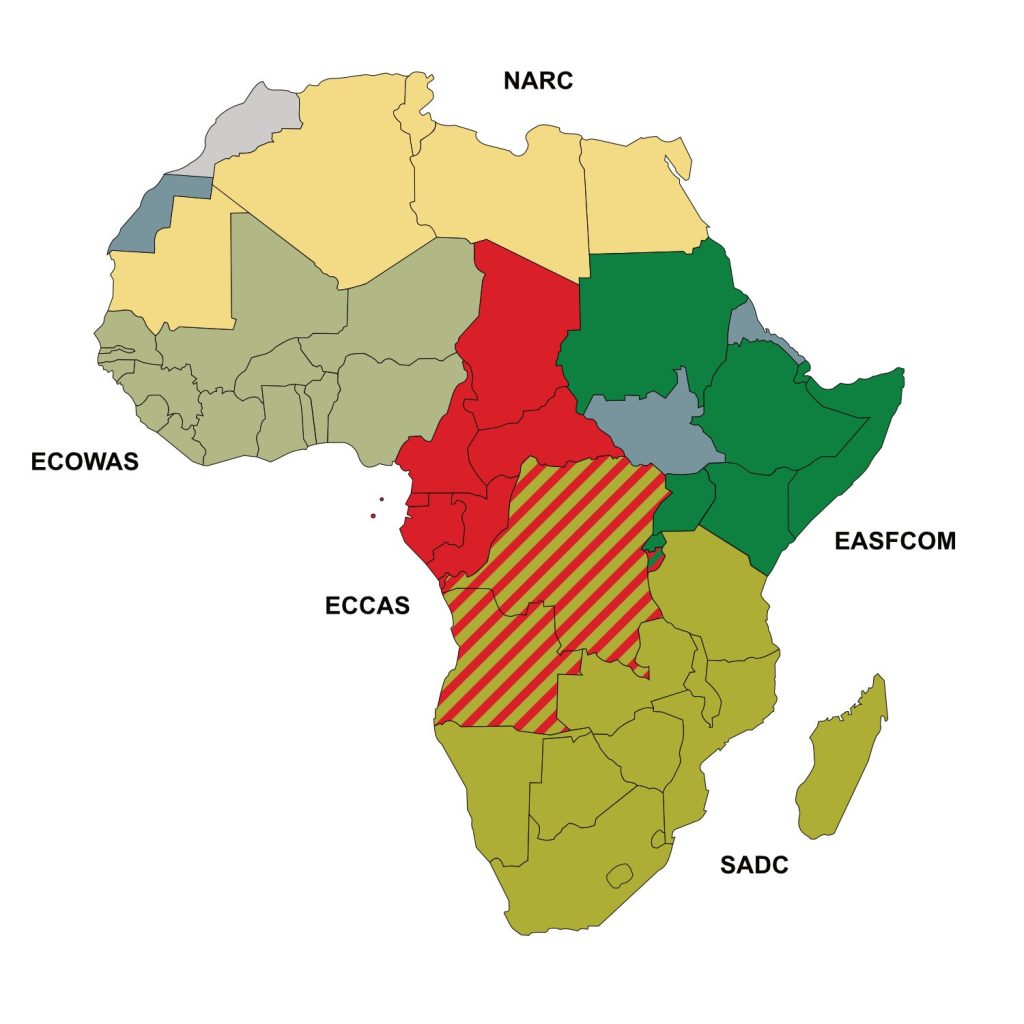

Since the 2000s, 38 African-led peace operations have been authorised and deployed in 25 countries.10 The AU has mandated, authorised or endorsed around 23 PSOs between 2003 and May 2024.11 ECOWAS has authorised six PSOs, followed by the OAU with four PSOs. The Economic Community of Central African States’ (ECCAS) and SADC have authorised two each. One PSO has been authorised by the member states of the Accra Initiative, Community of Sahel-Saharan States (CEN-SAD), and East African Community (EAC).12

African-led peace operations perform a wide range of functions, including ceasefire monitoring, stabilisation, counter-terrorism, peacebuilding, electoral observation, and humanitarian missions.13 African-led missions often demonstrate African agency where regional bodies and African states are empowered to manage their own security challenges, moving beyond reliance on external actors.14 Some operations are hybrid and organic coalitions that often involve partnerships among the AU, RECs, and other African states, with increasing use of tailored, short-term, organic ad hoc coalitions, such as MNJTF, G5 Sahel and the Accra Initiative, to respond to specific conflict contexts.15 The missions primarily focus on security, physical protection, and stability in crisis-ridden environments; they are also crucial for preventing conflict and enforcing ceasefires where peace is not yet established.16 These diverse mandates, as elaborated upon by Allen, are displayed in Table 2.

Table 2: African-led peace operations17

| Category | Examples |

| Ceasefires, peace processes, or peace agreements | OAU Joint Monitoring Commission to the DRC (JMC)OAU/AU Liaison Mission in Ethiopia-Eritrea (OLMEE/AULMEE)OAU Observer Mission in the Comoros (OMIC) 2ECOMILECOMICAMIB AMISMOUACA |

| Support elections and transition processes | OAU Observer Mission in the Comoros (OMIC) OMIC 3ECCAS’ Multinational Force in Central African Republic (FOMUC)AU’s Electoral and Security Assistance Mission (MAES)ECOMIB |

| Provide protection for leaders facing internal unrest | CEN-SAD ForceECOMIGAU Technical Support Team to The Gambia (AUTSTG)SADC Preventative Mission in the Kingdom of Lesotho (SAPMIL) |

| Stabilisation or peace enforcement operations against complex insurgencies or extremist groups | AMISOM Regional Cooperation Initiative for the Elimination of the Lord’s Resistance Army (RCI-LRA)MNJTFG5 Sahel Joint ForceSAMIMEAC Peace Mission in the DRC |

| Combat health crises and pandemics | AU Support to the Ebola Outbreak in West Africa (ASEOWA)AU Support to the Ebola Outbreak in the DRC (ASEDCO) |

The African Standby Force: Progress so far

The ASF was conceptualised under the APSA to provide a mechanism for peace operations by the AU. Article 13 of the PSC Protocol particularly outlines the establishment of the ASF as one of the APSA pillars. As a peacekeeping intervention of the AU envisaged under the Protocol, the ASF is to be deployed in pursuit of a decision of the PSC for the promotion of peace and security.18 Significant effort and investment have been made toward the development of policies, structures, regional capabilities and operationalisation of the ASF over the past 20 years. For instance, the ASF has advanced the establishment and operationalisation of regional standby brigades within the five African RECs. The AU has adopted policy frameworks and roadmaps to guide the ASF’s establishment, clarifying its military, police, and civilian components.19 The AU, through the PSC, oversees the ASF’s mandate and deployment, establishing command and control structures that enhance coordination during peace missions.

Critical gaps and practical barriers

Despite the progress in the operationalisation of the ASF, obstacles, including financial resources, political will, and logistical and strategic capability, have impeded its advancement.20 Political will emanating from the lack of consensus among member states, RECs/RMs and the AU over decision‐making, command and control, deployment, and the ASF mandating process has undermined seamless coordination.21 Logistical capabilities, especially strategic airlift and the creation of regional depots to support operations, are noticeably lacking. While the Continental Logistics Base (CLB) in Douala, Cameroon, has been established, Regional Logistics Depots (RLDs) are often incomplete or under-resourced, limiting readiness and rapid deployment capabilities. The supply of essential resources for logistics, reconnaissance and mobility is affected by significant financial shortfalls and dependence on external donor support that has dwindled over the years. The failure of member states to commit predictable, sufficient resources affects everything from training exercises to deployment and sustainment of the Force. The dependence on external funding also risks delays, conditionality and constraints on autonomy.22

Another challenge relates to persistent issues of authority and coordination between the AU and RECs, with some RECs aiming to maintain more control over deployments inside their borders.23 This is partly because the principle of subsidiarity, which should specify what RECs/RMs can or must do versus what the AU must do, is not clearly defined, leading to overlaps and duplications.24 Due to limited clarity regarding roles, functions, and makeup, the civilian (rule of law, civil affairs, human rights, gender, etc.) and police components of the ASF, which are critical for multidimensional peace operations, have fallen behind the military component.This is further complicated by the interoperability issues of differing equipment, doctrines, languages, training standards, and rules of engagement among member states, which make joint action difficult.25

Furthermore, there appears to be a mismatch between the operational environment and the ASF Framework. Originally designed for traditional peacekeeping, the operational environment today is affected by hybrid threats, including violent extremism, transnational crime, terrorism, pandemics, and climate shocks.26 However, the ASF has not been able to adapt effectively to these evolving threats. This has created a vacuum for the emergence of ad hoc coalitions such as the MNJTF and the Accra Initiative to occupy the space, often outside of ASF structures and AU oversight. While these ad hoc coalitions have helped to address urgent threats, they have also made it more difficult to build a fully operational, credible and unified ASF.

The varied readiness levels acrossregions in terms of training, capabilities, or administrative infrastructure are another barrier. The North and Central African regional brigades have, for example, made less progress in this respect.27 Regular exercises to test deployment, command and control, logistics, and coordination among all components (military, police, civilian) are also weak. Lastly, there is a lack of clarity in defining clear mandates in terms of what ASF missions are expected to do – enforcement versus peacekeeping versus stabilisation, as well as exit and transitional strategies.28

Future of African-led PSOs

African-led PSOs represent an indispensable pillar of continental security as they offer political legitimacy, local knowledge, and responsiveness. As most UN missions on the continent continue to draw down, and the security threats continue to intensify, Africa must own the tools and the vision of its PSOs, or risk perpetual crisis management shaped by external actors. Yet, the future of African-led PSOs remains at a crossroads. While the future of PSOs will largely be shaped by the emerging security threats, decline of UN peace operations, shifting geopolitical alignments, and growing demand for African agency and ownership in the peace process, it will also depend on how the continent moves from fragmented, reactive deployments to coherent, sustainable, and legitimate mechanisms rooted in African priorities. The ability to consolidate the various ad hoc coalitions, including the MNJTF, the Accra Initiative and the SADC Mission in Mozambique (SAMIM) under a unified, legitimate and sustainable security architecture like the ASF is crucial to the future of African PSOs. The path forward is neither purely technical nor solely political, but rather lies in an integrated approach that simultaneously addresses the institutional, financing, logistical, and normative gaps undermining African-led PSOs.

The ASF, as a key instrument for PSOs in Africa, still holds promise. However, it can only become fully operational if it is adapted to contemporary security realities and supported by tangible political and financial commitments by AU member states. Thus, there is a need for member states to transition from an episodic type of support to a more sustained, AU-led capacity investment, with a particular focus on predictable financing, AU-controlled logistics, modular capability packages, and reforms to decision-making. As the ASF becomes more agile, deployable, and integrated with RECs/RMs with a fully operationalised civilian and police component, it can evolve from a policy aspiration into a credible operational instrument of PSOs on the continent. Otherwise, the ASF risks remaining a normative or policy aspiration rather than being deployed as a unified, rapid instrument by the AU and RECs/RMs with a coordinated logistics and financing framework. Moreover, the RECs/RMs and ad hoc coalitions will continue to operate episodically with the support of external actors, increasing donor dependency and constraining African agency.

Conclusion and recommendations

The historical trajectory of African-led PSOs reflects both a determined assertion of African agency and a pragmatic response to the continent’s increasingly complex security landscape. The AU, RECs/RMs and member states have progressively taken ownership of peace and security on the continent with the deployment of PSOs across several countries. This not only demonstrates growing experience but also the increasing adaptability and political will of African states and regional organisations to take ownership of African problems. However, while some progress has been made, the ASF, which was conceived as the linchpin of Africa’s collective security response, has largely remained a strategic framework instead of a fully functional operational tool. It continues to face persistent challenges relating to politics, logistical readiness, financing and coordination among the AU, RECs/RMs, and ad hoc coalitions. These challenges have created space for ad hoc coalitions to fill the gap and have fragmented the peace and security landscape. The worrying aspect, however, is that the reliance on ad hoc coalitions has diluted coherence with the ASF framework.

As Africa’s security landscape grows more complex and UN peace operations continue to scale down, it is imperative to strengthen the ASF as a credible and operational peace support mechanism. Achieving this requires a multi-pronged approach that addresses the political, financial, institutional, and operational gaps. First, member states must demonstrate stronger political will by providing sustained financial contributions to the AU Peace Fund to operationalise ASF mechanisms and reduce the current overreliance on external donors, which often undermines autonomy and delays response times. Second, there is a need for a strategic reassessment of the ASF’s role and mandate by the AU and RECs/RMs to ensure that its doctrine and operational planning align with contemporary and emerging threats, such as terrorism. Third, it is critical to clarify the principle of subsidiarity between the AU and RECs/RMs to help minimise overlaps, institutional friction, and confusion in decision-making, command structures, and deployment authority. Fourth, the ASF’s logistics and deployment readiness must be significantly enhanced by accelerating the development of the RLDs and fully operationalising the CLB under AU-controlled stockpiles and management systems. Fifth, the AU and RECs/RMs must invest in recruitment, training, and deployment frameworks for the ASF’s civilian and police components, which are critical to fulfilling complex PSO mandates, especially those involving civilian protection, rule of law, and post-conflict reconstruction. Relatedly, it is essential to enhance the standardised interoperability protocols to enable cohesive operations across all regional brigades. Finally, there is the need for the AU to integrate operational lessons from the ad hoc coalitions into ASF doctrine, planning, and deployment strategies to build on what has worked and avoid duplication.

Dr Festus Kofi Aubyn, is the Regional Coordinator, Research and Capacity Building at WANEP.

Dr Naila Salihu is a senior lecturer at the Kofi Annan International Peacekeeping Training Centre.

Endnotes

1Addae-Mensah, L.; Aubyn, F. K.; and Baffour, O. F. (2024) ‘Mediating Complex Conflicts in Africa: Reflections on Multi-Stakeholder Approaches’, Discussion Points of the Mediation Support Network (MSN) No. 12.

2Tchie, Y. A. and McGowan, L. (2025) ‘The United Nations–African Union Partnership and the Protection of Civilians’, International Peace Institute (IPI), Available at: https://www.ipinst.org/2025/03/the-united-nations-african-union-partnership-and-the-protection-of-civilians [Date accessed: September 26, 2025]; Allen, N. and Mazurova, N. (2024) ‘African Union and United Nations Partnership Key to the Future of Peace Operations in Africa’, Africa Center, Available at: https://africacenter.org/spotlight/african-union-united-nations-peace-operations [Date accessed: September 26, 2025].

3Muchie, M., Gumede, V., Oloruntoba, S., and Check, N. A. (Eds) (2016) Regenerating Africa: Bringing African Solutions to African Problems, Pretoria: Africa Institute of South Africa, Available at: https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctvh8r2t1

4AU (2002) ‘The Protocol Relating to the Establishment of the Peace and Security Council of the African Union’, 9 July, Available at: https://au.int/en/treaties/protocol-relating-establishment-peace-and-security-council-african-union [Date accessed: September 26, 2025 ].

5Aning, K. and Edu-Afful, F. (2016) ‘African Agency in R2P: Interventions by African Union and ECOWAS in Mali, Cote D’ivoire, and Libya’, International Studies Review, Presidential Special Issue, 18(1): 120–133.

6Salihu, N. and Aning, K. (2023) ‘Ghana Armed Forces’ Contributions to African-Led Peace Support Operations from 1990-2020, Journal of International Peacekeeping, 26: 293–312.

7Salihu, N. and Birikorang, E. (2024) ‘Charting a New Path? Resolution 2719 and the Future of African-led Peace Operations’, Policy brief 15, Accra: KAIPTC.

8Tchie, E. A. Y. (2025) ‘The Role of Ad Hoc Security Initiatives and Enterprise Security Arrangements in the Protection of Civilians in Africa’, September, IPI.

9AU Peace Support Operations Division (2025) ‘AU Peace Support Operations Division’, Available at: https://www.aupaps.org/en/page/7-peace-support-operations [Date accessed: September 5, 2025].

10Allen, N. D. F. (2023) ‘African-Led Peace Operations: A Crucial Tool for Peace and Security’, Africa Center, Available at: https://africacenter.org/spotlight/african-led-peace-operations-a-crucial-tool-for-peace-and-security [Date accessed: September 5, 2025 ].

11Amani Africa (2023) The African Union Peace and Security Council Handbook 2023: Guide on the Council’s Procedure, Practice and Traditions, Addis Ababa: Amani Africa.

12Allen, N. D. F. (2023) ‘African-Led Peace Operations, op. cit.

13Ibid.

14Tchie, A. E. Y. (2023) ‘Generation three and a half peacekeeping: Understanding the evolutionary character of African-led Peace Support Operations’, African Security Review, 32(4): 421–439, Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/10246029.2023.2237482

15Tchie, A. E. Y. (2023) ‘African-Led Peace Support Operations in a declining period of new UN Peacekeeping Operations’, Global Governance: A Review of Multilateralism and International Organizations, 29(2): 230–244, Available at: https://doi.org/10.1163/19426720-02902006

16Ibid.

17Allen, N. D. F. (2023) ‘African-Led Peace Operations, op. cit.

18Amani Africa (2024) ‘The future of the African Union Peace and Security Council at 20: From a Promising Past and a challenge present to less certain future?’ Africa Report No. 20.

19Kasumba, Y. and Charles, D. (2010) ‘An Overview of the African Standby Force (ASF)’, In: de Coning, C. and Kasumba, Y. (Eds), The Civilian Dimension of The African Standby Force, Durban: ACCORD.

20Amani Africa (2025) ‘Update on the Operationalisation of the African Standby Force (ASF)’, Available at: https://amaniafrica-et.org/update-on-the-operationalisation-of-the-african-standby-force-asf [Date accessed: September 24, 2025].

21Ibid.

22Williams, P. D. (2011) ‘The African Union’s Conflict Management Capabilities’, Working Paper, Council on Foreign Relations, Available at: https://www.cfr.org/report/african-unions-conflict-management-capabilities [Date accessed: September 5, 2025 ].

23Amani Africa (2023) ‘Beyond subsidiarity: Understanding the roles of the AU and RECs/RMs in peace and security in Africa’, Africa Report No. 16.

24Fouda, A. D. (2022) ‘Towards the Operationalization of the African Standby Force (ASF)?’ On Policy, Available at: https://onpolicy.org/towards-the-operationalization-of-the-african-standby-force-asf [Date accessed: September 7, 2025 ].

25Abuja School (2024) ‘Challenges and Opportunities for Standby Forces in West Africa: Strengthening Regional Security and Democracy’, Available at: https://abujaschool.org.ng/title-challenges- [Date accessed: September 5, 2025].

26Minko, A. E. (2025) ‘The African Standby Force’s Deployment Efficiency in Sudan’, Available at: https://www.accord.org.za/analysis/the-african-standby-forces-deployment-efficiency-in-sudan [Date accessed: September 21, 2025].

27Amani Africa (2025) ‘Update on the Operationalisation of the African Standby Force’, op. cit.

28Minko, A. E. (2025) ‘The African Standby Force’s Deployment Efficiency in Sudan’, op. cit.