Mr Efehi Raymond Okoro is a Lecturer in the Department of Political Science and Public Administration at the University of Benin, Benin City, Nigeria.

Abstract

Terrorist acts by Boko Haram have attracted enormous scholarly attention in recent years. A majority of the studies have implicated Islam in the emergence and dynamics of the uprising. In contrast to this popular view, this article argues that, despite the strategic role played by Islamic religion in the uprising, terrorism and its security threats in northern Nigeria are more a product of a governance crisis including pervasive corruption, growing youth unemployment and poverty. It further argues that if good governance concurrently with development is not employed as a remedial strategy, the Nigerian State will further create a much more enabling environment for the growth of resistance from below. Thus, it concludes that good governance and credible leadership practices are antidotes to terrorism in Nigeria.

Introduction

Nigeria has played host to a terrorist scourge in recent years. Prior to the implementation of the Amnesty Programme in the Niger Delta, the oil hub was ravaged by a youth rebellion aimed at attracting more federal government presence and development to the oil-producing area of Nigeria. The militancy was also fuelled by the clamour for environmental security of the region whose ecosystem and livelihoods had been substantially undermined by nefarious oil extractive activities. But as relative peace returned to the Niger Delta, the Boko Haram (henceforth BH) rebellion broke out in the northern region of the country, dashing the hope of Nigeria’s return to sustainable peace in the post-amnesty era.

The BH uprising has proved more ferocious than the Niger Delta militancy, deploying the lethal strategy of suicide bombing – hitherto unknown in the country. Thousands of people have been killed and property worth millions of dollars has been destroyed since 2009 when BH first appeared. Most analysts of the conflict contend that Islamic fundamentalism is at the root of the rebellion; a few scholars blame the emergence on elite violent political competition between northern and southern Nigeria, especially after Goodluck Jonathan emerged as president; yet a handful of analysts attribute the political violence to external influences, including the influx of illegal aliens into the country.

This article unravels the weaknesses in these explanations and demonstrates that the BH insurgency is a fall-out of a governance crisis, especially in northern Nigeria where the growing incidence of poverty has led to frustration and recourse to violence among the people, particularly the youth. The article is divided into six sections: immediately following this introduction is the second segment which conceptualises the terms ‘governance’ and ‘terrorism’.

The third part is on the theory of state fragility, while the fourth part examines the evolution and dynamics of BH insurgency. The fifth section explains why violent conflict is pervasive in northern Nigeria. The sixth and final segment concludes the article.

Governance and terrorism: A conceptualisation

In a broad sense, the concept ‘governance’ refers to the process of exercising political power to manage the affairs of a nation or society. Governance entails the process of making decisions and implementing them as based on considerations such as popular participation, respect for the rule of law, observance of human rights, transparency, free access to information, prompt responses to human needs, accommodation of diverse interests, equity, inclusiveness, effective results and accountability (UNICEF 2002). Focusing on outputs and outcomes of policy, the Mo Ibrahim Foundation sees governance as the provision of the political, social and economic public goods and services that a citizen has the right to expect from his or her state, and that a state has the responsibility to deliver to its citizens (IIAG 2013:6).

The core elements of governance include (1) the process by which those in authority are selected, monitored and replaced, (2) the capacity of the government to effectively manage its resources and implement sound policies, and (3) the respect of citizens’ fundamental rights (Santiso 2009). Thus, the concept translates into: initiating, directing and managing public resources, organising people, directing subordinates to put in their best to achieve positive results in a given assignment (Lawal et al. 2012:187). On the other hand, governance crisis simply connotes those problems that emanate from the misapplication of the key elements of the concept in a society. This often spurs resentment or rejectionist behaviour from its citizens who are expected to be loyal and law-abiding.

Various attempts have been made to conceptualise terrorism, but none has been universally accepted. Little wonder the term ‘terrorism’ is classified as one of the most contentious concepts in recent political parlance. The contentious nature of the concept is understandable, given the complex nature of the term, particularly if one draws from the ideological interpretations of ‘one man’s terrorist is another man’s freedom fighter’, which has become a justification for the violent acts of both state and non-state actors in a bid to contrast one side’s legitimate killing to another side’s illegitimate killing and also blur the distinctions between acts of non-state terrorism and state terrorism (Hough 2008:66; English 2009:4).

From a subjective perspective, this right of legitimate killing(s) is considered a right of state(s), since in international law state violence is viewed through the prism of legality whereas violence from non-state actors is viewed or perceived illegal in its totality (Hough 2008:66). From this point of view, the term ‘terror’ is something that can be inflicted upon people either by governments (state terrorism) or by groups (groups like Al-Qaeda, Al-Shabaab and Boko Haram). Therefore it is hardly surprising that the concept terrorism is derived from the Latin word ‘terrere’ meaning to frighten, terrify, deter, or scare away (English 2009:5). Indeed a terrorist act can involve all of (but is not limited to) these elements sketched out above.

Thus, terrorism is a particular species of political violence involving a threat of violence against non-combatants or property in order to gain a political, ideological, or religious goal through fear and intimidation. Usually symbolic in nature, the act is crafted to have an impact on an audience that differs from the immediate target of the violence. Hence terrorism is a strategy employed by actors (state and non-state actors) with widely differing goals they intend to achieve and constituencies they intend to reach (Post 2007:3; Enders and Sandler 2012:4).

Theorising state fragility

In the modern political sensibility, the concept of state fragility (as that of the countries of the ‘bottom billion’) is highly contentious (Collier 2007:7). This is because of the complex and diverse nature of states which are referred to as fragile. Despite this contention, several scholars and development agencies define state fragility principally as a fundamental failure of the state to perform functions necessary to meet citizens’ basic needs and expectations through the political process (Mcloughlin 2012:9). Theoretically, state fragility can be understood as a composite measure of all aspects of state performance, such as authority, service delivery and legitimacy, that characterise the state (Brown 2009, cited in European Report on Development 2009:16).

Although there are different levels of state(s) ranking in the global arena, some are strong while others are either fragile or collapsed (Zartman 1995:1; Reno 2002:843). However, if these states are placed on a continuum based on their ranking, a fragile state will be one which has not been able to perform its core duties as a centralised organisational structure, is unable to exercise its sovereign rights and is incapable of making binding decisions on its citizens, and lacks an effective engine of growth and appreciable development. Thus, a sovereign state which has lost total control of its duties or has failed to perform these duties is thus referred to as failed or collapsed (Carment 2003:409-410; Osaghae 2007:692).

However, a fragile state as opposed to a collapsed or a failed state may be defined most simply as a distressed state that lacks the key elements necessary to function effectively. According to Osaghae (2007:692-693), fragile states are specifically characterised by one or more of the following:

- Weak, ineffective, and unstable political institutions and bad governance, conducive to loss of state autonomy; informalisation; privatisation of state, personal and exclusionary rule; neo-patrimonialism; and prebendal politics.

- Inability to exercise effective jurisdiction over its territory, leading to the recent concept of ‘ungoverned territories’.

- A legitimacy crisis, occasioned by problematic national cohesion, contested citizenship, violent contestation for state power, perennial challenges to the validity and viability of the state, and massive loss and exit of citizens through internal displacement, refugee flows, separatist agitation, civil war and the like.

- Unstable and divided population, suffering from a torn social fabric, minimum social control, and pervasive strife that encourage exit from rather than loyalty to the state.

- Underdeveloped institutions of conflict management and resolution, including credible judicial structures, which pave the way for recourse to conflict-ridden, violent, non-systemic and extra-constitutional ways in which to articulate grievances and seek redress.

- Pervasive corruption, poverty, and low levels of economic growth and development, leading to lack of fiscal capacity to discharge basic functions of statehood, including, most importantly, obligations to citizens such as protection from diseases like AIDS and guarantees of overall human security.

It is based on these characteristics and theoretical underpinnings that it becomes appropriate to classify Nigeria as a fragile state because a majority of the characteristics sketched out above are clear features in the country. Thus, one finds a link between Nigeria’s weakness and the emergence and dynamics of terrorist operations in the country, especially from the BH group in the troubled north.

Boko Haram: Anatomy of a rebellion

The code name ‘Boko Haram’ (BH) was formed out of two separate words ‘Boko’ and ‘Haram’. The term ‘Boko’ is the Hausa name for western education, while ‘Haram’ is an Arabic word which figuratively means ‘sin’ but literally means ‘forbidden’. When these words are used together in the Hausa language, it denotes strongly that western education is forbidden (Adesoji 2010:100; Johnson 2011). However, the name BH is strongly rejected by the group who prefers to be officially called ‘Jama ‘atu Ahlis Sunna awati wal-jihad’ (‘People committed to the propagation of the Prophet’s teachings and Jihad’, or, more literally translated, ‘Association of Sunnas for the Propagation of Islam and for ‘Holy War’) (see Sani 2011:24; Osumah 2013:541).

The exact date of BH’s origin is mired in controversy, but most Nigerian sources agree on the parallel – if not direct connection in terms of individuals involved – with the Maitatsine uprising of the 1980s, which was apparently one of the first attempts at imposing a religious ideology on a secular and independent Nigeria (Isichei 1987:194-208; Pham 2011:2). Despite all this, it is agreed by scholars that in 2002, a Muslim cleric, Ustaz (Teacher) Mohammed Yusuf, established a religious complex with a mosque and an Islamic boarding school in Maiduguri, Borno State. Thus the foundation of the BH group was established (Johnson 2011; Chothia 2012). The introduction of Islamic Law (Sharia) in 12 northern states since 1999 was deemed insufficient by those represented by Yusuf and his die-hard followers, who clearly argued that the country’s ruling class in its entirety was marred by corruption and even Muslim northern leaders were irredeemably tainted by ‘western-style’ ambitions. To them, a ‘pure’ Sharia state would ostensibly be more transparent and just than the existing order (Forest 2012:62-63; Pham 2012:2).

The group BH has a membership composition which includes: disaffected northern youths, professionals, unemployed graduates, Islamic clerics, ex-almajirai (children who constantly migrate for the purpose of acquiring Quranic education in the Hausa language), drop-outs from universities, plus some members of the Nigerian political elite. It also includes some members of the state security agencies who thus assist the group with training and useful intelligence reports. The sect claims to have over 40 000 members altogether in Nigeria and some neighbouring African states including Chad, Benin, and Niger (Onuoha 2010:57-58; Chris 2011; Forest 2012:62-63).

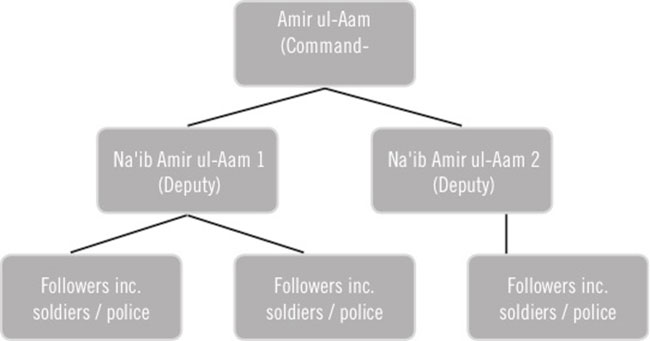

BH like several other militant groups keeps its membership diffuse; it does not publish full details of its hierarchies, structure, or manifesto. But a closer look at the group displays some forms of hierarchical structure, even though few details are known about its inner operations. Its first known leader was the Late Mohammed Yusuf (1979-2009), after whom Mallam Sani Umaru became the acting leader of the group. And since then several other members have claimed to be the leader of the group at different times (Campbell 2012). Currently Imam Abu Muhammed Abubakar aka Shekau is the group’s Commander-in-Chief (Amir ul-Aam), with Kabiru Sokoto and Mallam Abu Qaqa as deputies (Na’ib Amir ul-Aam 1 and 2) (Waldek and Jayasekara 2013:171; Zenn 2012:3).

Figure 1: Potential Leadership hierarchy of the BH Group

Interestingly, members of the militant group pay daily levies to their leaders, thus providing a financial base for BH in addition to loot from attacks on banks, ransoms from kidnapping and donations from political sponsors and other organisations within and outside Nigeria. For example, in 2007 Mohammed Yusuf and Mohammed Bello Damagun were arraigned in a Federal High Court at the Federal Capital Territory Abuja for receiving monies from Al-Qaeda operatives. It was alleged that Damagun for his part received a total of US$300 000 from Al-Qaeda to recruit and train Nigerians in Mauritania for terrorism. Similarly, Yusuf reportedly received monies from Al-Qaeda operatives in Pakistan to recruit terrorists who would attack the residences of foreigners, particularly Americans living in Nigeria (Onuoha 2010:56-57; Adesoji 2010:101; Campbell 2012).

The BH group is a security threat to Nigeria. Its first known violent attack, in which approximately 30 people were killed, was on local government installations, police stations as well as public buildings in Yobe State on 24 December 2003 (Pham 2011:1; Aghedo and Osumah 2012:859). In a bid to stop these attacks on police stations and other government buildings, the government of Nigeria in July 2009 launched a counter-attack against the insurgents which resulted in at least 700 deaths, mostly members of the group, and including the group leader Mohammed Yusuf, who was killed while in police custody (Ploch 2011:1-2).

Despite this government crackdown, the group which appeared to have gone into hibernation re-emerged in a much more deadly and highly militarised form, orchestrating a large scale prison break in September 2010 that saw the release of 700 prisoners, including over 100 of its own members (Alechenu and Makinde 2011). The group’s attacks have since increased substantially in frequency, reach and lethality, and are now occurring almost daily in a majority of northern states in Nigeria. They now periodically reach as far as the capital city of Abuja (Ploch 2013:12).

However, the implications of violent terrorist attacks are manifest in economic disintegration, and in wanton destruction of lives and properties in the troubled zone of the country. BH has since 2009 carried out sophisticated attacks on mainly police stations, army barracks, prisons, religious centres, schools, and banks as well as some other government institutions, and upon prominent personalities. These, plus the heavy-handed counter-insurgency operation against the group have caused an estimated 3 000 deaths, the destruction of property and significant displacement of people (HRW 2012; Murdock 2013). (See table 1 below for a sample list of attacks). Although the incidents listed in table 1 are neither exhaustive nor terminal, it is obvious that terrorist attacks in the country have surged rather than ebbed – an indication that the group’s activities have been expanding progressively in terms of scope, severity and targets from 2009 to the present time.

Table 1: A sample of Boko Haram attacks in Nigeria from July 2009 to September 2013

| S/N | Date | Incidents (Nature and Location) | Casualty Figures |

| 1. | July 26, 2009 | BH attacked police station in Bauchi triggering a five day uprising that spread to Maiduguri. | Over 40 sect members were killed and over 200 arrested. |

| 2. | September 7, 2010 | BH attacked a prison in Bauchi and freed 700 inmates former sect members inclusive | 5 guards killed |

| 3. | December 24, 2010 | Bomb attack in Jos | 8 people killed instantly |

| 4. | December 28, 2010 | BH claims responsibility for the Christmas eve bombing in Jos | 38 people killed |

| 5. | May 29, 2011 | Bombing of Army Barracks in Bauchi and Maiduguri | 15 people killed |

| 6. | June 26, 2011 | Bomb attack on a bar in Maiduguri | 25 people killed |

| 7. | August 16, 2011 | Bombing of the United Nations office complex in Abuja | Over 34 people killed |

| 8. | December 25, 2011 | Bombing of St. Theresa Catholic Church, Madalla | Over 46 people killed |

| 9. | January 21, 2012 | Multiple bomb blasts rocked Kano city | Over 185 people killed |

| 10. | February 15, 2012 | Attack on Koton Karfe prison, Kogi State, in which 119 prisoners were freed | 1 warder killed |

| 11. | February 19, 2012 | Bomb blast near Christ Embassy Church in Suleija, Niger State | 5 people killed |

| 12. | February 26, 2012 | Bombing of Church of Christ of Nigeria, in Jos | 2 people killed and 38 injured |

| 13. | March 8, 2012 | An Italian-Franco Lamolinara, and a Briton Christopher McManus, expatriate staff of Stabilim Visioni construction company, abducted since mid-2011, were killed by a splinter group of BH | 2 people killed |

| 14. | March 11, 2012 | Bombing of St. Finbarr’s Catholic Church, Rayfield, Jos | 11 people killed and many injured |

| 15. | April 26, 2012 | Bombing of three media houses:(a) This Day, Abuja(b) This Day; The Sun and the Moments, Kaduna | 5 people killed and 13 injured in Abuja3 people killed and many injured in Kaduna |

| 16. | April 29, 2012 | Attack on Bayero University, Kano | 16 people killed and many injured |

| 17. | April 30, 2012 | Bomb explosion in Jalingo | 11 people killed and several others wounded |

| 18. | September 23, 2012 | A suicide bomber attacked St. John’s Catholic Church in Bauchi | 2 persons killed and over 48 injured |

| 19. | December 5, 2012 | Attack in Kano City on policemen at a roundabout and civilians in a bus | 2 policemen killed and several others injured |

| 20. | March 23, 2013 | Attack in Kano, Adamawa, Borno. Banks, police station and a prison torched | 28 killed and several others injured |

| 21. | April 12, 2013 | Attack in Yobe police station | 4 policemen and 5 sect members killed |

| 22. | June 22, 2013 | Attack in Yobe in Bama town | 40 police men, 13 prison warders, 3 soldiers and several other civilians killed |

| 23. | September 29, 2013 | Attack in Yobe State College of Agriculture in Gijba | 78 Students killed |

Sources: Ajayi, 2012:106; Onuoha 2010:59; Muhammad, Marama and Yusuf 2013; Bello and Musa 2013:1; BBC Africa 2012; Marama 2013; Vanguard 2013.

The increased militarisation of the BH group, resulting in frequent attacks on both civilians and foreign nationals in Nigeria, has also caused a large dent to the nation’s image. Indeed, its citizens and the international communities now interact with the state in an extremely cautious manner. Also, no investor would want to invest in a terrorist-prone zone where the watchword is insecurity. Thus, creating a generalised sense of insecurity in the country and beyond due to acts of terrorism (like Farauk Umar Abdulmurtallab who attempted to bomb an American airliner with over 289 people on board) is still fresh in the minds of everyone. This case and several others have lent credence to fears that Nigeria is a fertile ground for Al-Qaeda recruitment and consequently an emerging exporter of international terrorism (Olaosebikan and Nmeribeh 2010; Johnson 2011).

Sadly, the strategic importance of a nation’s image re-branding cannot be over-emphasised as this, according to Ham and Jun (2008), enhances those socio-political and economic factors as well as values that are crucial to the harmonious working relations of states in the international community. Nation branding can attract both tangible and intangible benefits, including tourism revenue, investment capital, and foreign aid; and can boost its cultural and political influence in the global arena. However, the increased terrorist threats from the BH militants in the country have all clearly undermined the government’s Nation’s Image Re-branding policy aimed at achieving a positive image turnaround (Ojo and Aghedo 2013:82).

Bringing governance into the crisis: Explaining the BH uprising

The emergence of the BH sect in Nigeria has triggered widely divergent views on the real instigator of the group’s emergence, growth and agenda. And, since then, available literature on the propellant of the group’s construction has been coloured with mixed motives, ranging from political, religious and external to socio-economic ones. A majority of scholarly authors shares the view that political ideology is the key propellant of the emergence and growth of the recent terrorist acts from the BH sect. It is their argument that the current form of terrorism is fuelled by the recent political shift of power from the hands of the northern political elites to their southern counterparts as exemplified by the Jonathan Presidency (Ahokegh 2012:47; Maiangwa and Uzodike 2012:3).

Thus, the Nigerian political space became over-heated when President Umar Musa Yar’Adua died, and as a result of the Nigerian Constitution the Vice-President Goodluck Jonathan became the substantive President with an alleged signed agreement to only complete the remaining one year of the erstwhile president, as based on the People’s Democratic Party’s (PDP) principle of zoning. President Jonathan, however, vigorously contested such an agreement, and has consistently denied signing any agreement. Others argue that zoning is not a constitutional matter but a ‘gentleman’s agreement’. The implication of the thesis supporting this political motive is hinged on the logic that the BH group was constructed by some northern political elites who had lost face in the April 2011 presidential election and as such were bent on making the country ungovernable for President Jonathan who is a Christian minority southerner. Seen this way, the BH becomes a child of political rascality (Osuni 2012; Forest 2012:27; Nwanegbo and Odigbo 2013).

It is true that a majority of Nigerian politicians are intoxicated with politics since the premium placed on political power is quite high, but it is completely illogical to hinge the BH uprising on politics alone. This is because the BH had long been in existence before the alleged flagrant disregard of the PDP’s principle of zoning in 2011. The group first came into prominence under President Musa Yar’Adua who was a northern Muslim.

Despite this political thinking, there exists another dimension in the interpretation of the emergence and growth of the terrorist sect. Some scholars have argued that the recent form of terrorism from the BH group is an outgrowth of the Maitatsine Movement and riots of the 1980s during which the first major uprisings of fundamentalist Islam in Nigeria appeared with the stated goal of purifying Islam. The reason for this interpretation is that some of the key actors of the Maitatsine crisis were also implicated in the recent BH formation, thus creating a link between the same old objectives of the Islamic crisis of the 1980s with that of the recent acts of terrorism (Adesoji 2010:96-97).

Advocates of a link between Maitatsine and BH argue that the main enabling factor to the evolution of BH was the partial implementation and adoption of the contested Sharia law in 12 Northern states in the country starting from 2000, which many religious faithful of Islam have been trying to turn into full implementation ever since the time of the Maitatsine riots. To them, even the name BH speaks to such experiences when interpreted in the local Hausa language (Boas 2012:1-4). According to this view BH’s origins and activity in recent time is a clear display and means of venting their anger regarding the way the government of Nigeria has handled the implementation of the long awaited Sharia law (Buah and Adelakun 2009:40). Thus, the recent acts of terrorism carried out by the BH group have a fundamentalist jihadist aspect to them. Indeed, Islamic religion has played a very significant role in the emergence and growth of the BH group. This is as a result of the fact that members of the group use religion to rationalise their acts and as such indoctrinate foot soldiers that the uprising is a fight for Allah and therefore a huge reward awaits its members.

However, despite this very important role played by religion in the evolution of the group, the relationship between Islam and the dynamic character of BH terror remains tenuous. This is because proponents of this ideology fail to note the fact that religious beliefs in Nigeria are normally pushed to rationalise conflict by groups such as BH, but that they are more of a smoke screen for the real ends served by violence. Therefore, even though the narratives of the insurgents have been religiously driven, especially in pursuit of jihadism (in order to fully implement Sharia law), the membership profile of the group indicates very strongly that poverty and economic inequality are at its roots. In addition, the group which claims to be focused on achieving an all-encompassing Islamic state unleashes terror even on those it is supposedly fighting for – fellow Islamic faithful.

There is an opposing argument from scholars which places the key elements of the outset of the BH uprising in an external context, insisting that the recent forms of terrorism from the group are to a large extent alien to the Nigerian people and as such implicates an external dimension to the sect’s origin and agenda. This analytical model gained momentum when in 2011 the United Nations House in Abuja fell victim to a vehicle-borne improvised exploding device (V-IED) launched by a member of the BH group (Connell 2012:87; Ajayi 2012:105).

The thrust of the external dimension argument is hinged on the ideology that foreign terrorist organisations are responsible for the recent terror attacks in the country. This is because of the fact that there is a significant increase in the involvement of illegal aliens in the BH attacks. Chadians, Nigeriens, Malians, among others, have all been identified in the nation’s recent security challenges in which the new tactic of suicide bombing has been used. It is argued that a true Nigerian will not commit suicide for the sake of achieving a particular goal. The Nigerian government has deported a significant number of illegal aliens in its hope to avert terrorist attacks. For example, in Lagos well over 50 illegal aliens were handed over to the immigration for screening and onward deportation to their countries (Ugbodaga 2013).

However, this analytical model is deficient because the major actors fingered in the construction of the BH group were clearly identified as citizens of Nigeria, drawn primarily from the Kanuri ethnic group (concentrated in the north-east region, especially Bauchi and Borno), but also from the entire northern region of the country (Chris 2011; Forest 2012:1). Therefore, it is instructive to note that this analytical tool for understanding the BH uprising is not cogent enough and thus lacks merit. Scholars and researchers have often overlooked the core motive for the group’s origin, objectives and growth as an up-shoot of a governance crisis, rising unemployment, mass poverty, and rampant corruption. My point here is that the weak nature of governance in Nigeria serves a wider function in the emergence and growth of terrorist groups such as BH.

It is a fact that after fifty four years since gaining independence (1960-2014), a majority of Nigerians still cannot meet their basic human and socio-economic needs. A large percentage of the youth lacks access to food, a quality educational system, effective healthcare service delivery, pipe-borne water, proper shelter, and employment opportunities. Yet in the face of these deprivations, the political elites embezzle public funds and engage in ostentatious living. The inability of the government to bring about good and effective governance for its citizens particularly in the northern region has created what Omede (2011:93) referred to as a ‘frustration of rising expectations’ which has in turn resulted in all forms of violence in the region, including such crimes as kidnapping, armed robberies and most importantly terrorism which has reached its acme.

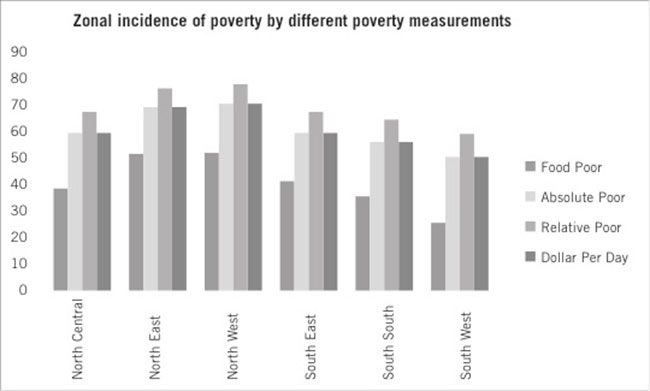

Though governmental corruption and its attendant mass poverty are rampant throughout the country, the rate of poverty in the northern region is higher than the national average (see Figure 2).

Figure 2: Zonal incidence of poverty in Nigeria

Indeed, several studies conducted with a focus on poverty incidence in the region clearly indicate that about 75 per cent of Northerners live in poverty compared to 27 per cent of Southerners (Pothuraju 2012:3). Similarly a study on national poverty levels from the Central Bank of Nigeria also concluded that ten states with the highest level of poverty are all located in the northern region, conversely ten states with the lowest level of poverty are all southern states, and as a result 70 per cent of the people living in the north live on below $1 per day (US$1 = N150) (Lukman 2007). See Table 2 for incidence of poverty in Nigeria.

Table 2: Poverty by region, Nigeria

| 1980 | 1985 | 1992 | 1996 | 2004 | 2010 | |

| Nationwide | 28.1 | 46.3 | 42.7 | 65.6 | 54.4 | 69.0 |

| Sector | ||||||

| Urban | 17.2 | 37.8 | 37.5 | 58.2 | 43.2 | 61.8 |

| Rural | 28.3 | 51.4 | 66.0 | 69.3 | 63.3 | 73.2 |

| Geopolitical zone | ||||||

| South-South | 13.2 | 45.7 | 40.8 | 58.2 | 35.1 | 63.8 |

| South-East | 12.9 | 30.4 | 41.0 | 53.5 | 26.7 | 67.0 |

| South-West | 13.4 | 38.6 | 43.1 | 60.9 | 43.0 | 59.1 |

| North-Central | 32.2 | 50.8 | 46.0 | 64.7 | 67.0 | 67.5 |

| North-East | 35.6 | 54.9 | 54.0 | 70.1 | 72.2 | 76.3 |

| North-West | 37.7 | 52.1 | 36.5 | 77.2 | 71.2 | 77.7 |

Source: Ojo and Aghedo 2013:95

Sadly, the above data paint a pretty dismal picture of the socio-economic situation in Nigeria, thus reinforcing the argument of this article that citizens were repulsed by the government’s weakness or failure to provide the basic human needs, and instigated by the example of Niger Delta militants who utilised violence as a bargaining chip to obtain concessions from the government, as well as by the failure of non-violent strategies – such as protests or negotiations. All of these factors, strengthened by the youth’s disillusionment, made them ready armies in the hands of extremists like Yusuf.

Even the borders of the Nigerian state have not been spared from the dire consequences of its fragility. This is manifest in the poor management of the nation’s borders. The recent disclosure by Nigeria’s Minister of Interior, Abba Moro, that there are over 1 497 irregular (illegal) and 84 regular (legal) officially identified entry routes into Nigeria, confirms the very porous state of these borders which permits illicit transnational arms trafficking in the country (Abbah and Igidi 2013; Onuoha 2013:4). It is thus not surprising that terrorist groups take advantage of the poorly managed borders for smuggling sophisticated weapons into the country. This is evidenced by BH’s sophistication in heavy fire power such as anti-aircraft weapons mounted on four-wheel-drive vehicles, and by their access to arms smuggled out of Libya which are now used by the insurgents to resist government forces (Alli and Ogunwale 2013; Gambrell 2013).

The fragility of public institutions and the state security apparatus makes terrorist groups such as BH more radicalised in both tactics and targets. This is because these security agencies have failed to strictly abide by the rules of engagement in tackling perpetrators of terrorist acts when they respond to these in Nigeria. It is a fact that terrorist groups such as BH conducted their operations and campaigns in a more or less peaceful manner during their infant stage (Cook 2011:8). But this changed due to the state’s brutal suppression leading to the deaths of over 700 members of the group including the group’s leader Ustaz Mohammed Yusuf in 2009 (Nwankwo and Falola 2009). This strengthened the hands of the BH insurgents who, taking advantage of the widespread impoverishment of the northern people, radicalised them on the pretext that Islamic religion was under threat (IDMC-NRC 2013:4).

Perhaps the poor management of victims of terrorism by the state is also a manifestation of fragility. Both insurgent and counter-insurgent activities have triggered a significant displacement of citizens both internal (internally displaced persons – IDPs) and external (externally displaced persons – EDPs). For example, on 2 May 2013 President Jonathan declared a state of emergency in Borno, Yobe and Adamawa states. Both insurgent and counter-insurgent efforts at the time resulted in the displacement of over 9 000 Nigerians to Niger, Cameroon and Chad (UNHCR 2013). Furthermore, Nigeria suffers a shortage of humanitarian aid to cushion the negative impacts of displacement on victims (IDMC-NRC 2013:6). Nigeria’s growing weakness in the fight against terrorism is further exacerbated by government security forces’ human rights abuses.

Despite the fact that the Nigerian constitution guarantees that every person has the ‘right to life’, ‘personal liberty’ and ‘respect for the dignity of his person’, and shall not be arbitrarily deprived of these rights, including the right not to be subjected to torture or inhuman or degrading treatment (Constitution of the Federal Republic of Nigeria 2011: sections 33, 34(1)(a) and 35), government security forces, comprising military, police, and intelligence personnel (known as the Joint Military Task Force, JTF), have arbitrarily executed, arrested or beaten civilians, burned houses and cars, illegally detained civilians, and have subjected some to torture or other physical abuse (HRW 2012). For example, as many as 950 people with suspected BH links have died in military detention centres in the first six months of 2013 alone, according to an estimate of Amnesty International (2013).

The great expectations of the people that these social ills would ebb with Nigeria’s return to a democratic government have nearly been dashed owing to successive bad governance from its leaders to date. Just recently Nigeria ranked 41st out of Africa’s 52 nations in safety and rule of law, participation and human rights, sustainable economic opportunity and human development according to the statistical measure of governance performance in African countries (IIAG 2013:9). The above-mentioned cases of institutional decay plus the high levels of youth unemployment, poverty and developmental challenges in the northern regions have influenced terrorist groups in Nigeria. These factors, combined with weak governance, rampant corruption, inadequate public service delivery, and increased human rights violations have contributed to widespread disaffection and are the major propellant of terrorism in the area.

However, contemporary history has come to recognise that the Nigerian state is unable to discharge many of its statutory functions, including those ensuring development, guaranteeing welfare, minimising corruption, and regulating peoples’ monopoly of violence. The implication of these contradictions and social pathologies arising from the fragility of the Nigerian state is that if good governance concurrent with development is not employed as curative to past government ills, the Nigerian State will further create a much more enabling environment for the growth of more terrorist groups other than the BH sect. It is not only that these stark realities have not been taken into account by the leaders of Nigeria’s counter-terrorism committee, but also that they have not hesitated to do so at the expense of peace and have thus left the strategy of counter-terrorism grappling with symptoms rather than tackling the menace.

Concluding remarks

The article has argued that the phenomenon of the BH uprising is driven more by poor governance and illegitimate leadership practices than the religious variables analysts and authors have strongly emphasised. It has been demonstrated that the rates of mass poverty in the northern region are higher than the national average, with the result that many people have become disaffected, frustrated and pushed to rebellion. Though jihadist rhetoric is often stated by the insurgents as the core motivation of the terrorism, this narrative is more of a legitimising and mobilising tool than a precipitant. The religious twist to the uprising cannot be ignored, however; this is because, as mentioned in the article, Islam had played a crucial role in at least providing the group with more members who are willing to die for the cause which the group seeks to promote. In light of this religious dimension, however, proper monitoring of the teachings of various religious groups in the country is important in a bid to prevent any group from using religion as a spring-board for the actualisation of their economic benefits in Nigeria.

There is also a strong need in Nigeria for an accountable, legitimate and transparent governance that will bring about popular participation through inclusiveness but not alienation and exclusion, which will ultimately result in people-centred development. In this sense the government of Nigeria should be sensitive, fair and just in the discharge of its duties, decisions and policies in a way that will positively affect the lives of the general public instead of continuously serving the interests of the political elites. This will make the government a peace generator rather than a conflict escalator. On the economic front there is need for proper macro-economic management aimed at poverty alleviation and drastic reduction in the levels of inequality and unemployment. This is because there can be no good governance without a viable economic base.

Finally, rather than continually using brutal force as conflict management strategy, the government should work more on strengthening the governance system in Nigeria and should focus, with the help of international donors, on developmental projects aimed at reducing poverty, unemployment and corruption. This may help to contain the insurgency, because BH ‘writ large’ is a movement of grassroots anger among northern people at the continuing depravation, poverty and economic inequality which have been the direct result of bad governance in the north and the country at large. These measures should depopulate the pool of foot soldiers from which the violent elites draw.

Sources

- Abbah, Theophilus and Terkula Igidi 2013. We’ll build physical fences at illegal routes into Nigeria – Abba Moro. Sunday Trust. Available from: <http://www.sundaytrust.com.ng/index.php/interview/12387-we-ll-build-physical-fences-at-illegal-routes-into-nigeria-abba-moro> [Accessed 17 March 2013].

- Adesoji, Abimbola 2010. The Boko Haram uprising and Islamic revivalism in Nigeria. African Spectrum, 45 (2), pp. 95-108.

- Aghedo, Iro and Oarhe Osumah 2012. The Boko Haram uprising: How should Nigeria respond? Third World Quarterly, 33 (5), pp. 853-869.

- Ahokegh, Akaayar 2012. Boko Haram: A 21st century challenge in Nigeria. European Scientific Journal, 8 (21), pp. 46-55.

- Ajayi, Adegboyega 2012. Boko Haram and terrorism in Nigeria: Exploratory and explanatory notes. Global Advanced Research Journal of History, Political Science and International Relations, 1 (5), pp. 103-107.

- Alechenu, John and Femi Makinde 2011 Government arrested, released UN bombing suspects in 2007. The Punch, 2 September.

- Alli, Yusuf and Gbade Ogunwale 2013. Boko Haram fighters resist troops with Libyan arms. The Nation. Available from: <http://issuu.com/thenation/docs/may_22__2013> [Accessed 12 December 2013].

- Amnesty International 2013. Nigeria: Deaths of hundreds of Boko Haram suspects in custody requires investigation. Available from: <http://www.amnesty.org/en/news/nigeria-deaths-hundreds-boko-haram-suspects-custody-requires-investigation-2013-10-15> [Accessed 12 November 2013].

- BBC (British Broadcasting Corporation) Africa 2012. Nigerian church bombed in Bauchi, Boko Haram flashpoint. Available from: <www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-Africa-19691781> [Accessed 11 September 2012].

- Bello, Niyi and Njadvara Musa 2013. Boko Haram rejects proposed amnesty, denies wrongdoing. The Guardian, 29 April.

- Boas, Morten 2012. Violent Islamic uprising in northern Nigeria: From the ‘Taliban’ to Boko Haram II. Norwegian Resource Peacebuilding Centre (NOREF) article.

- Buah, Juliet and Abimbola Adelakun 2009. The Boko Haram tragedy and other issues.

The Punch, 6 August. - Campbell, John 2012. Nigeria’s insistent insurrection, The New York Times. Available from: <http://www.nytimes.com/2012/01/26opinion/nigeria-insistent-insurrection.html?> [Accessed 25 January 2013].

- Carment, David 2003. Assessing state failure: Implications for theory and policy. Third World Quarterly, 24 (3), pp. 407-411. Available from: <http://http-server.carleton.ca/~dcarment/papers/assessingstatefailure.pdf> [Accessed 20 August 2013].

- Chothia, Farouk 2012. Who are Nigeria’s Boko Haram Islamists? BBC News. Available from: <http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-africa-13809501> [Accessed 11 January 2013].

- Chris, Ajaero 2011. A thorn in the flesh of the nation. Newswatch, 21 November, pp.12-19.

- Collier, Paul 2007. The bottom billion: Why the poorest countries are failing and what can be done about it. Oxford, Oxford University Press.

- Connell, Shannon 2012. To be or not to be: Is Boko Haram a foreign terrorist organization? Global Security Studies, 3 (3), pp. 87-93.

- Constitution of the Federal Republic of Nigeria (Amended) 2011. Available from: <http://www.nigeria-law.org/ConstitutionOfTheFederalRepublicOfNigeria.htm#Chapter_1>[Accessed 29 November 2013].

- Cook, David 2011. Boko Haram: A prognosis. James A. Baker III Institute for Public Policy of Rice University. Available from: <http://www.bakerinstitute.org/files/735/> [Accessed 15 May 2012].

- Enders, Walter and Todd Sandler 2012. The political economy of terrorism. 2nd Edition. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press.

- English, Richard 2009. Terrorism: How to respond. Oxford, Oxford University Press.

- European Report on Development 2009. Overcoming fragility in Africa. Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies, European University Institute, San Domenico di Fiesole. Available from: <http://ec.europa.eu/europeaid/what/development-policies/research-development/documents/erd_report_2009_en.pdf> [Accessed 20 October 2013].

- Forest, James 2012. Confronting the terrorism of Boko Haram in Nigeria. JSOU (Joint Special Operations University) Report, 2 (5), pp. 1-178.

- Gambrell, Jon 2013. Boko Haram’s weapons of war spilling innocent blood in Nigeria. Associated Press. Available from: <http://www.cananusa.org/index.php/campaigns/news/349-boko-haram-s-weapons-of-war-spilling-innocent-blood-in-nigeria.html> [Accessed 20 October 2013].

- Ham, Chang D. and Jong W. Jun 2008. Cultural factors influencing country images: The case of American college students’ attitude towards South Korea. Journal of Mass Communication, 2 (3), pp. 1-22.

- Hough, Peter 2008. Understanding global security. 2nd edition. London and New York, Routledge, Taylor and Francis Group.

- HRW (Human Rights Watch) 2012. Spiralling violence: Boko Haram attacks and security forces abuses in Nigeria. Available from: <http://www.hrw.org/sites/default/files/reports/nigeria1012webwcover.pdf> [Accessed 12 December 2013].

- IDMC-NRC (Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre – Norwegian Refugee Council) 2013. Fragmented response to internal displacement amid Boko Haram attacks and flood season. Available from: <http://www.internal-displacement.org/8025708F004CE90B/(httpCountries)/19D5FDB3E4AF4D1D802570A7004B613E?OpenDocument> [Accessed 16 November 2013].

- IIAG (Ibrahim Index of African Governance) 2013. 2013 Ibrahim index of African governance: Summary. Mo Ibrahim Foundation. Available from: <http://www.moibrahimfoundation.org/downloads/2013/2013-IIAG-summary-report.pdf> [Accessed 26 November 2013].

- Isichei, Elizabeth 1987. The Maitatsine risings in Nigeria, 1980-1985: A revolt of the disinherited. Journal of Religion in Africa, xvii (3), pp. 194-208.

- Johnson, Toni 2011. Backgrounder: Boko Haram, Council on Foreign Relations. Available from: <http://www.cfr.org/africa/boko-haram/p25739> [Accessed 27 January 2013].

- Lawal, Tolu, Kayode Imokhuede and Ilepe Johnson 2012. Governance crisis and the crisis of leadership in Nigeria. International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences, 2 (7).

- Lukman, Salihu M. 2007. Nigeria: The north and poverty phenomenon. Available from: <http://allafrica.com/stories/200702060158.html> [Accessed 18 September 2012].

- Maiangwa, Benjamin and Ufo Uzodike 2012. The changing dynamics of Boko Haram terrorism. Report, Aljazeera Centre for Studies, pp. 1-6.

- Marama, Ndahi 2013. Boko Haram re-groups, invades Borno towns. Vanguard, Vol. 24, 23 June.

- Mcloughlin, Claire 2012. Topic guide on fragile states. Governance and Social Development Resource Centre. University of Birmingham, UK. Available from: <http://www.gsdrc.org/docs/open/CON86.pdf> [Accessed 18 July 2013].

- Muhammad, Abdusalam, Ndahi Marama and Umar Yusuf 2013. As 28 are killed in terror attacks … Insurgents hit bank, police station, prisons. Vanguard, 24 March. Available from: <http://www.vanguardngr.com/2013/03/as-28-are-killed-in-terror-attacks-insurgents-hit-bank-police-station-prisons/> [Accessed 19 November 2013].

- Murdock, Heather E. 2013. In army fight against militants, Nigerian civilians trust no one. Global post. Available from: <http://www.globalpost.com/dispatch/news/regions/africa/nigeria/130521/africa-nigeria-boko-haram-al-qaeda-military> [Accessed 14 October 2013].

- Nwanegbo, Jaja and Jude Odigbo 2013. Security and national development in Nigeria: The threat of Boko Haram. International Journal of Humanities and Social Science, 3 (4), pp. 285-291.

- Nwankwo, Chiawo and Francis Falola 2009. Boko Haram: Another 140 kids, women rescued, 780 killed in Maiduguri alone – Red Cross victims given mass burial. The Punch, 3 August.

- Ojo, Uyi and Iro Aghedo 2013. Image re-branding in a fragile state: The case of Nigeria. The Korean Journal of Policy Studies, 28 (2), pp. 81-107.

- Olaosebikan, O. and M. Nmeribeh 2010. The making of a bomber. The NEWS, 11 January.

- Omede, Adedoyin 2011. Nigeria: Analysing the security challenges of the Goodluck Jonathan administration. Canadian Social Science, 7 (5), pp. 90-102.

- Onuoha, Freedom C. 2010. The Islamist challenge: Nigeria’s Boko Haram crisis explained. African Security Review, 19 (2), pp. 54-67.

- Onuoha, Freedom C. 2013. Porous borders and Boko Haram’s arms smuggling operations in Nigeria. Report, Aljazeera Centre for Studies.

- Osaghae, Eghosa E. 2007. Fragile states. Development in Practice, 17 (4), pp. 691-699.

- Osumah, Oarhe 2013. Boko Haram insurgency in Northern Nigeria and the vicious cycle of internal insecurity. Small Wars and Insurgencies, 24 (3), pp. 536-560.

- Osuni, P. 2012. Azazi blames PDP for security problems. Saturday Sun, 28 April.

- Pham, J. Peter 2011. Paper on ‘Boko Haram – Emerging threat to the U.S. Homeland’ presented before the Committee on Homeland Security: Subcommittee on Counterterrorism and Intelligence Hearing. Congressional Research Service, 30 November. Available from: <https://homeland.house.gov/hearing/subcommittee-hearing-boko-haram-emerging-threat-us-homeland> [Accessed 23 June 2013].

- Pham, J. Peter 2012. Boko Haram’s evolving threat. Africa Security Brief, 20, pp. 1-7.

- Ploch, Lauren C. 2011. Paper on ‘Boko Haram – Emerging threat to the U.S. Homeland’ presented before the Committee on Homeland Security: Subcommittee on Counterterrorism and Intelligence Hearing Congressional Research Service, November 30. Available from: <https://homeland.house.gov/hearing/subcommittee-hearing-boko-haram-emerging-threat-us-homeland> [Accessed 23 June 2013].

- Ploch, Lauren C. 2013. Nigeria: Current issues and U.S. policy. Congressional Research Service, Washington, D.C.

- Post, Jerrold M. 2007. The mind of the terrorist: The psychology of terrorism from the IRA to Al-Qaeda. New York, Palgrave Macmillan.

- Pothuraju, Babjee 2012. Boko Haram’s persistent threat in Nigeria. IDSA (Institute for Defence Studies and analyses) Backgrounder. Available from: <http://www.idsa.in/system/files/threatinnigeria_babjepothuraju.pdf> [Accessed 23 October 2013].

- Reno, William 2002. The politics of insurgency in collapsing states. Development and Change, 33 (5), pp. 837-858. Oxford, Blackwell Publishers.

- Rogers, Paul 2012. Nigeria: The generic context of the Boko Haram violence. Oxford Research Group Monthly Global Security Briefing, April 30.

- Sani, Shehu 2011. Boko Haram: History, ideas and revolt. The Constitution, 11 (4). Journal of the Centre for Constitutionalism and Demilitarisation (CENCOD), Ikeja, Nigeria. Lagos, Panaf Press.

- Santiso, Carlos 2009. Good governance and aid effectiveness: The World Bank and conditionality. The Georgetown Public Policy Review, 7 (1). Available from: <http://www.sti.ch/fileadmin/user_upload/Pdfs/swap/swap108.pdf> [Accessed 18 June 2013].

- Ugbodaga, Kazeem 2013. Fear of Boko Haram: Mass deportation of illegal aliens. P.M. News Available from: <http://pmnewsnigeria.com/2013/03/26/fear-of-boko-haram-mass-deportation-of-illegal-aliens/> [Accessed 15 June 2013].

- UNHCR (United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees) 2013. NE Nigeria insecurity sees refugee outflows spreading to Cameroon. Briefing Notes. Available from: <http://www.unhcr.org/51c036549.html> [Accessed 11 December 2013].

- UNICEF (United Nations Children’s Fund) 2002. Poverty and exclusion among urban children. New York, UNICEF. Available from: <http://www.unicefirc.org/publications/pdf/digest10e.pdf> [Accessed 12 December 2013].

- Vanguard 2013. Gunmen massacre 78 students in Yobe. Available from: <http://www.vanguardngr.com/2013/09/gunmen-massacre-78-students-yobe/> [Accessed 3 October 2013].

- Waldek, Lise and Shankara Jayasekara 2013. Boko Haram: The evolution of Islamist extremism in Nigeria. Journal of Policing, Intelligence and Counter Terrorism, 6 (2), pp. 168-178.

- Zartman, I. William 1995. Collapsed states: The disintegration and restoration of legitimate authority. Boulder, CO, Lynne Rienner.

- Zenn, Jacob 2012. Boko Haram’s dangerous expansion into Northwest Nigeria. CTC (Combating Terrorism Center) Sentinel, 5 (10), pp. 1-5. Journal of the Combating Terrorism Center at West Point, New York.