Abstract

In Tanzania, conflicts over land resources between pastoralists and farmers have been pervasive, especially in Mvomero District despite numerous efforts by the government to resolve them. This study is based on secondary data concerning the persistence of conflict, complemented by thematic analysis of six key informant interviews from three villages in Mvomero District: Kambala, Bungoma and Mkindo. The goal is to understand the evolving nature of land conflicts, the effectiveness of conflict-resolution mechanisms and the impacts on both farmers and pastoralists. The findings reveal that efforts to address land conflicts are hindered by several factors: inadequate resources, low levels of knowledge and awareness about land matters, the absence of village land councils, a lack of Village Land Use Plans (VLUPs), especially in pastoralist-dominated villages and insufficient and uncoordinated information. Drawing on theories of principled negotiation and conflict resolution, this paper argues that there is no single resolution strategy suitable for all conflicts, as each setting is unique even within the same village. Nonetheless, coercive methods remain common, with paramilitary and government officials often employed instead of negotiated solutions. Since this approach offers only short-term relief, land conflicts tend to recur repeatedly. In light of these findings, the paper recommends that stakeholders should follow up initial coercive interventions with negotiated approaches to ensure long-term stability. To this end, the effective implementation of the Village Land Act (1999) and the Land Disputes Courts Act (2019) requires the development of operational guidelines and tools that support negotiated solutions in line with the principles of principled negotiation theory.

1. Introduction

Land conflict is a social phenomenon involving at least two parties with roots in differing interests over land property rights (Wehrmann, 2017). Moore (2012) argues that globally, about 70% of the planet’s land is potentially subject to conflict due to the absence of clear titles. Long-standing land issues continue to hamper poverty-reduction initiatives. Additionally, Haning et al. (2022) state that offences in the land sector may be codified in criminal law or regulated outside it. These conflicts can take various forms, including boundary disputes, multiple sales and allocations of land, destruction of property and disputes over different land uses; thus, such conflicts often coexist (Wehrmann, 2017).

The level of security in land tenure reflects the extent to which an individual’s land rights are recognised and protected in the face of potential disputes (Edeh et al., 2022). As competition for land increases, the likelihood of conflict rises. In rural Africa, land conflicts are often attributed to disruptions in the traditional link between land and livelihood, driven by the commercialisation of land. This has led to increased competition, where wealthier individuals acquire large plots, commonly referred to as land grabbing (FAO, 2006). Multiple factors such as unemployment, ownership disputes, poor governance, poverty, rapid population growth, marginalisation and social inequality contribute to the emergence of land grabbers, bandits and even terrorists (Stanton et al., 2021).

Scholars such as Massay (2017), Garner (2022), Enyindah and Amugo (2021) and Mohamed (2015) report tensions between farmers and pastoralists in various parts of the world, including Tanzania, Burkina Faso (Mossi farmers vs Fulani pastoralists), Nigeria (Hausa vs Fulani) and Kenya (Pokomo farmers vs Orma pastoralists). These conflicts are often driven by inadequate access to resources, differing beliefs and values, relational dynamics, territorial claims, language, ethnicity, self-determination, inequality and revenge (Alananga, 2019; Ringo, 2023; Falanta and Bengesi, 2024). In India, land conflicts arise from population growth, tribal claims, settlement issues, development projects, pastoralism, tourism, land acquisition for corridors and farming (Burke, 2014). Land disputes commonly erupt during farming seasons when communities compete for agricultural space (Nwokafor et al., 2020). Boundary conflicts may also stem from social divisions such as class, ethnicity or religion and may occur at personal, village or even international levels (Ntumva, 2020; Falanta and Bengesi, 2024). In some cases, land conflicts emerge from corrupt practices like double allocations orchestrated by unscrupulous village officials for personal gain (Sackey, 2010).

Falanta and Bengesi (2024) and Massoi (2015) support the environmental security theory, which posits that conflicts arise due to competition over limited resources. Benjaminsen et al. (2009) emphasise the theory’s relevance in explaining how resource scarcity triggers intergroup competition. Overgrazing, for example, results from too many animals grazing in a particular area or prolonged grazing in the same spot (Mwamfupe, 2015). The rise in livestock numbers contributes to recurrent conflicts between farmers and pastoralists. Such conflicts are attributed mainly to increasing pressure on natural resources, driven by expanding livestock herds and the encroachment of cultivation (Falanta and Bengesi, 2024). A significant challenge remains the limited capacity of local governments to manage these conflicts due to resource constraints (Makupa and Alananga, 2021). While regulations have attempted to address family-, community- and use-based land disputes, a permanent solution remains elusive across much of Africa (Fratkin, 2014).

Tanzania faces land conflicts on multiple fronts. Researchers such as Ntumva (2020), Falanta and Bengesi (2024) and Haning et al. (2022) have explored the causes, impacts, responses and the mediating role of village leaders in resolving land disputes between farmers and pastoralists. A notable case is the violent conflict between pastoralists and farmers in Kilosa District, Morogoro Region, which resulted in the loss of life and property (Ntumva, 2020). Other conflict-prone areas include Kilosa, Mvomero, Ulanga and Kilombero Districts in Morogoro Region; Kilindi and Handeni in Tanga Region; Mbarali in Mbeya; Arumeru and Kiteto in Arusha; Rufiji and Mkuranga in Pwani; Kongwa in Dodoma; and Hai in Kilimanjaro (Mwamfupe, 2015).

During droughts, pastoralists practice transhumance, moving their herds far from home in search of pasture and water. This often results in livestock grazing on farm crops, leading to conflict (Mung’ong’o and Mwamfupe, 2003). Falanta and Bengesi (2024) note that the Mvomero District in Morogoro Region is particularly vulnerable to land conflicts. The influx of nomadic pastoralists has contributed to a rise in disputes over land use, boundaries and ownership despite the district’s abundance of arable and grazing land (Ringo, 2023). These conflicts contribute to land tenure insecurity, reduced agricultural productivity, loss of life and destruction of property and crops. One notable example involves Maasai pastoralists disputing ownership of small ranches created in 2003 following the privatisation of Dakawa Ranch. The ranch was subdivided and allocated to various stakeholders, including private companies, local farmers and indigenous livestock keepers. Saruni et al. (2018) report that indigenous livestock keepers were granted 5,019 hectares, divided into 100-hectare ‘mini-ranches’ that were sold to Maasai pastoralists, eventually leading to conflicts over ownership.

The increasing intensity of land conflicts prompted government interventions in the case study areas: Kambala, Mkindo and Bungoma villages in Mvomero District (Mwamfupe, 2015). Initiatives include involvement of state agencies, traditional institutions, establishment of ward land councils and the development of Village Land Use Plans (VLUPs), which involve allocating land for specific purposes such as cultivation and grazing. A VLUP is a participatory planning process that seeks to optimise land use within a village. It considers residential areas, commercial zones, open spaces and infrastructure needs (Huggins, 2016). The objective is to ensure sustainable, equitable and efficient land use (Stosch et al., 2022). In Kambala village, this approach led to the division of land into designated zones for grazing and farming (Mwamfupe, 2015).

While previous studies have identified causes, consequences and resolution mechanisms, few have evaluated the effectiveness of these mechanisms in reducing land conflict. Despite multiple government efforts, land disputes in Mvomero District continue to escalate, taking new forms, suggesting that the wrong tools may be in use. This study aims to assess the effectiveness of conflict-resolution mechanisms in enhancing land tenure security in the conflict-affected villages of Mkindo, Bungoma and Kambala in Mvomero District.

2. Literature review

Land conflicts have far-reaching consequences, including food insecurity, land tenure insecurity, destruction of property and even loss of life, which exacerbate communal and inter-ethnic tensions (Yamano and Deininger, 2018). Falanta and Bengesi (2024) acknowledge that women are disproportionately affected by climate change-related conflicts due to unequal gender roles and the unequal distribution of resources. Ntumva (2020) observed significant impacts of farmer-pastoralist conflicts in Kilosa District and noted a general decline in peace and security among affected communities. Falanta and Bengesi (2024) point out that food insecurity is often linked to land conflicts, as uncertainty surrounding ownership or claims undermines land tenure legitimacy and discourages agricultural investment.

Conflicting land rights can severely limit land use and development, hindering infrastructure expansion, investment and agricultural productivity, thus compounding food insecurity (Edeh et al., 2022). According to Ntumva’s (2020) study, nearly all participants in in-depth interviews and focus group discussions reported that land conflicts led to the destruction of homes (including burning of homesteads), rape, beatings, injuries and even death among both farming and pastoralist communities. The study highlights a growing social divide between the two groups, with mutual hostility escalating to the point where each views the other as an enemy.

In addition to food insecurity, these conflicts are perceived to stall economic development in the district. Farmers cited the presence of land conflicts in their villages as a major barrier to full engagement in agricultural activities (Ntumva, 2020). Other documented consequences include population displacement, with women and children being especially vulnerable, as men often flee more easily in times of crisis (IWGIA, 2015).

Traditionally, land conflicts were addressed through customary institutions that operated within local communities, guided by principles of reciprocity (Haning et al., 2022). This form of resolution relied on voluntary participation and involved a neutral third party — typically a respected community elder acting as a mediator to facilitate peaceful resolution without coercion (Ajayi and Buhari, 2014). Such processes emphasised peacebuilding and community harmony, often culminating in a celebratory feast to signify reconciliation (Ajayi and Buhari, 2014).

Unlike traditional mediation, moderation can be applied pre-emptively, before conflict escalates. It explicitly addresses destructive or dysfunctional behaviour that may stem from psychological trauma, such as the grief associated with past violence between conflicting groups (Shemdoe and Mwanyoka, 2015). In the context of this study, moderation is relevant, as pastoralists and farmers may opt to end hostilities through mutual forgiveness, recognising the shared suffering caused by previous conflicts (Krislov, 1987).

Alternatively, land conflicts may be resolved through arbitration. Unlike moderation, arbitration involves a powerful and neutral figure with decision-making authority who offers binding recommendations for conflict resolution. This method is particularly useful at the peak of conflict. Unlike legal adjudication, arbitrators are often selected by both parties and are individuals who command mutual respect, typically with traditional legitimacy (Wehrmann, 2015).

3. Conceptual framework

The institutional theory asserts that authoritative guidelines for behaviour, social norms and values are created and adopted over time (Hasunga et al., 2022). It also serves as a policy-making mechanism that emphasises the formal and legal aspects of government directives, which must be complied with (Kraft and Furlong, 2019). This theory aids in understanding the transactional costs and economic dynamics involved in land access processes. In the context of land conflicts, unclear institutional arrangements regarding land ownership — specifically the right to access resources within defined boundaries — emerge as a major source of contention (Francis et al., 2017).

In Tanzania, access to formal land is governed by a combination of state laws and regulations, market forces of supply and demand and customary land tenure systems (Adedayo, 2018). Each of these institutional mechanisms holds both legal authority and social legitimacy. The National Land Policy recognises land as a commodity with market value and emphasises its accessibility through market mechanisms. At the same time, the Village Land Act (1999) upholds customary ownership in rural areas, while the Land Act (1999) acknowledges both customary and market-based transactions, introducing land tenure typologies categorised as Village Land, General Land and Reserved Land.

This complex institutional arrangement often becomes a breeding ground for land-related conflicts, particularly in rural areas, where multiple actors may lay claims to the same land parcel based on different yet legitimate grounds. The conflict resolution theory (CRT) has developed valuable insights into the nature, sources and peaceful resolution of conflicts. It views social life as inherently competitive, particularly over scarce resources. Conflicts, therefore, arise from the interactions of competing groups. While the theory emphasises the importance of peaceful and participatory approaches to conflict resolution, it also acknowledges that coercive measures may sometimes be necessary to maintain order (Falanta and Bengesi, 2024). Ajayi and Buhari (2014) explain that conflict theory conceptualises society as a stage for competition over limited resources, a dynamic that influences all social interactions.

According to this perspective, social order is maintained not through consensus and conformity, but rather through domination and power. Those who control wealth and resources often exercise disproportionate influence over political processes and institutions, thereby marginalising the poor and powerless (Prayogi, 2023). In this context, power is defined not only as political authority but also as control over material assets, access to land and institutional legitimacy.

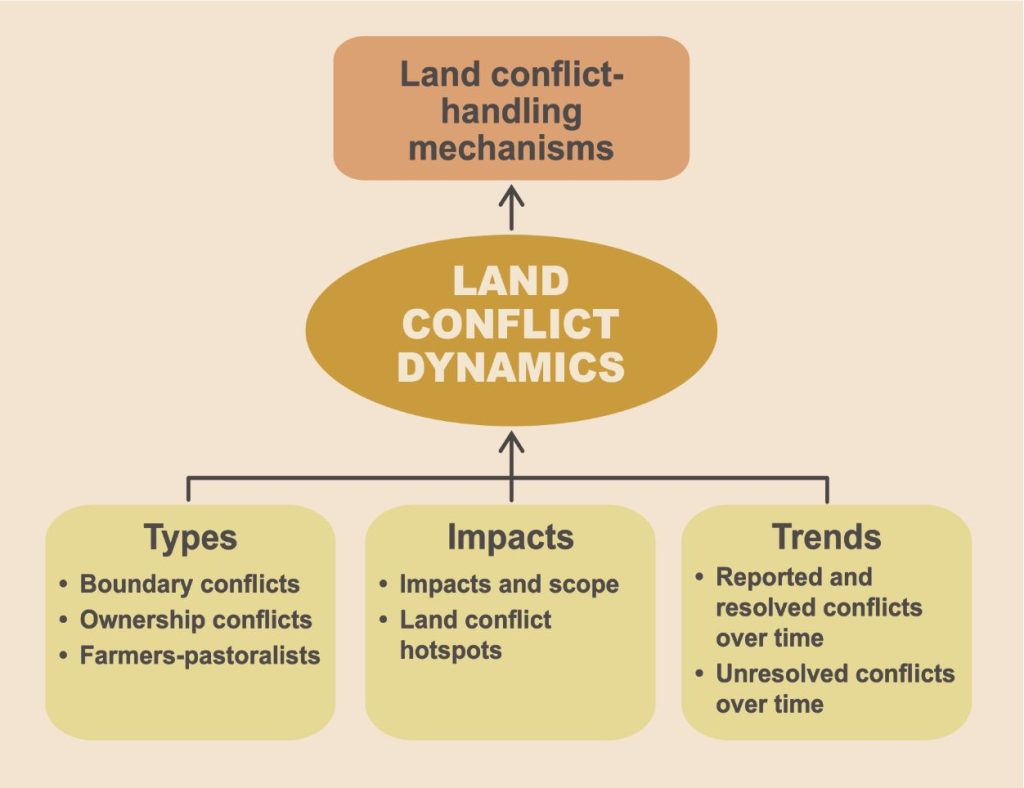

Figure 1: Conceptual framework

Source: Authors’ construction based on literature review

A more nuanced approach to conflict resolution is articulated through the concept of “principled negotiation”, as developed by Herman (2020). This model consists of four foundational tenets: (a) separate the people from the problem, (b) focus on interests, not positions, (c) invent options for mutual gain and (d) insist on using objective criteria. The first tenet, separating the people from the problem, acknowledges the diverse backgrounds, values, emotional responses and cultural contexts of the negotiating parties. Understanding these differences is essential before reaching any negotiated solution. Recommended strategies include developing empathy by ‘putting oneself in the other party’s shoes’, identifying the emotional underpinnings of the conflict and applying effective communication techniques to defuse misperceptions and hostilities.

The second tenet, focusing on interests rather than positions, involves distinguishing between the apparent conflict and the underlying needs or motivations of each party. For instance, although pastoralists and farmers may dispute over the same piece of land, their underlying interests such as securing grazing areas or cultivating fertile land may differ and could be reconciled. The third tenet, inventing options for mutual gain, calls for collaborative or independent exploration of solutions that consider the needs of both parties. These solutions can either satisfy shared interests or fulfil complementary interests, thereby creating opportunities for compromise and cooperation. Finally, insisting on objective criteria means that negotiated outcomes should be guided by agreed-upon standards such as market value, legal precedents or customary rules. These criteria should be mutually selected and voluntarily accepted to ensure fairness and legitimacy in the resolution process.

Figure 1 presents the conceptual framework for this study, illustrating how different types and impacts of land conflicts can influence the evolution of conflict-resolution mechanisms over time. While CRT emphasises peaceful and participatory approaches to resolving conflict, it also recognises that coercive methods may occasionally be necessary, depending on the situation. However, this study argues that coercive power is not universally applicable or effective in all contexts. In many cases, particularly those involving inter-community or resource-based disputes, participatory and negotiated approaches prove more relevant and sustainable (Easy Sociology, 2024). In this regard, principled negotiation theory provides a practical lens for conflict management by allowing affected parties to reach amicable solutions without external imposition.

4. Research methodology

This study adopted a qualitative research approach. The target population included local elders, farmers, pastoralists, village executive officers (VEOs) and village chairpersons in Mvomero District, Tanzania. These groups were selected on the basis of their direct involvement in land policy implementation (in the case of officials) and lived experience with land conflicts (for community members). Mvomero District was chosen as the study area because it encompasses villages that have historically experienced recurrent and severe land conflicts. Specifically, Kambala, Bungoma and Mkindo villages were purposively selected as representative sites because of their documented exposure to prominent land use disputes. Semi-structured interview guides were used because they offer flexibility, allow participants to elaborate freely on their experiences and provide greater depth and nuance (Barclay, 2018).

The qualitative data collected was analysed using thematic analysis. This was followed by a systematic coding process, using both manual methods and computer-aided theme identification tools. Emergent codes were then organised into themes. Some of these themes, particularly those related to conflict resolution, were pre-coded in accordance with CRT, which includes negotiation, mediation, adjudication, arbitration and reconciliation. Frequencies of coded responses were also quantified to provide insight into the relative emphasis placed on specific themes by respondents. Selected direct quotations from interviews and focus group discussions were included in the analysis to illustrate key points. Ethical integrity was a cornerstone of the study. Confidentiality and anonymity were strictly observed throughout the research process. Participants were informed about the purpose and benefits of the study to encourage open and honest participation. Care was taken to ensure that all data collection tools and interactions were free from bias regarding age, gender, race, ethnicity or disability. Interview questions were framed to avoid causing emotional distress.

5. Results and findings

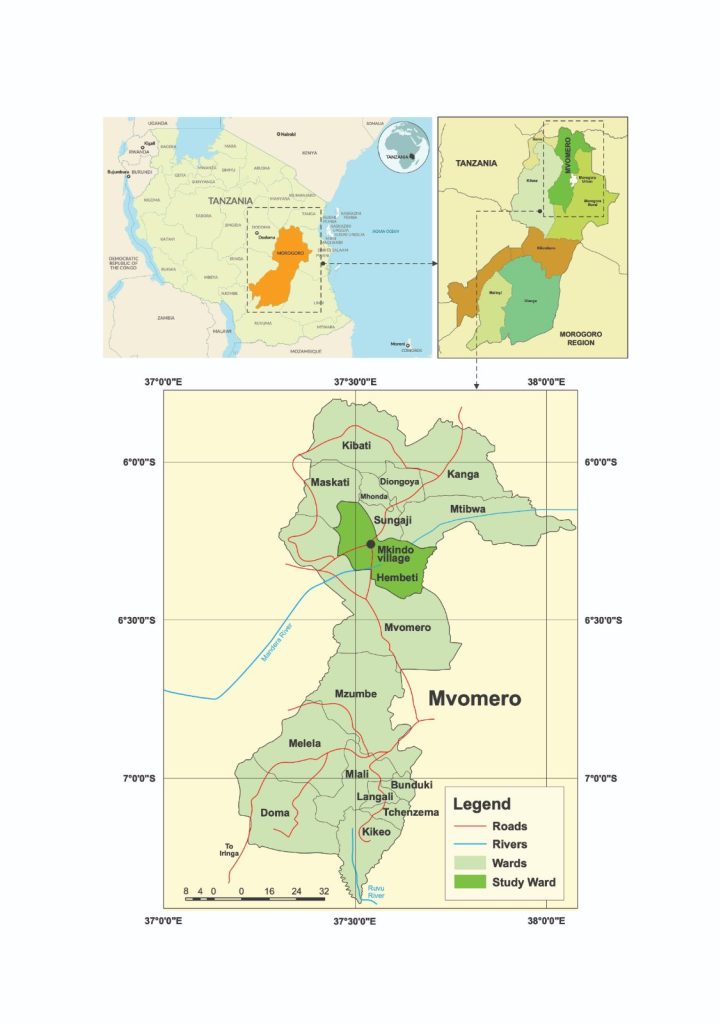

Mvomero District is one of the nine districts in the Morogoro Region. The district covers an area of 7,325 km². Of this, 549,375 hectares are suitable for agricultural activities and 247,219 hectares are currently under cultivation (approximately 45% of the suitable area). Additionally, 266,400 hectares are suitable for livestock rearing. Administratively, the district is divided into four divisions, 28 wards, 130 villages and 681 hamlets. Mkindo Ward is an administrative ward with a population of 15,523, comprising 7,846 males and 7,677 females, according to the 2022 Tanzania National Census. It is located within the Mvomero District Council, which has a population of 421,741, comprising 210,834 males and 210,907 females. Mkindo Ward consists of four villages: Mkindo, Bungoma, Kambala and Mndela. The area is inhabited by both farming communities and nomadic pastoralists. The geographical location of the ward is illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2: Map presenting the study area

5.1 Magnitude and nature of land conflicts in Mvomero

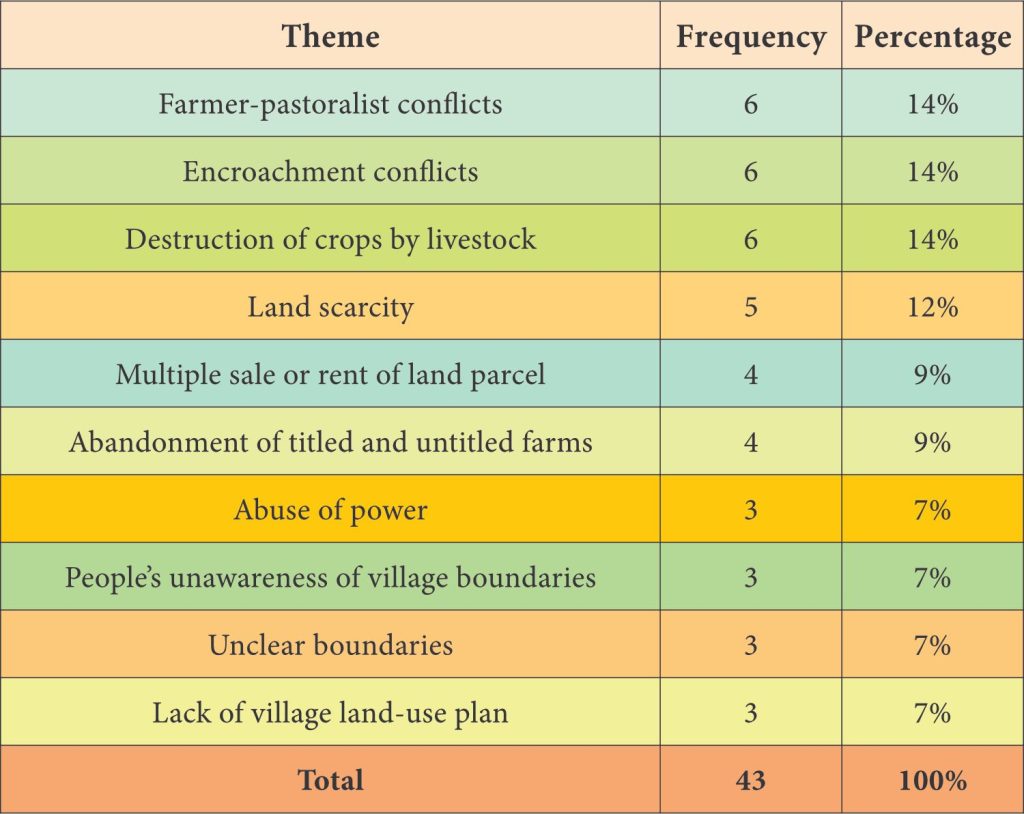

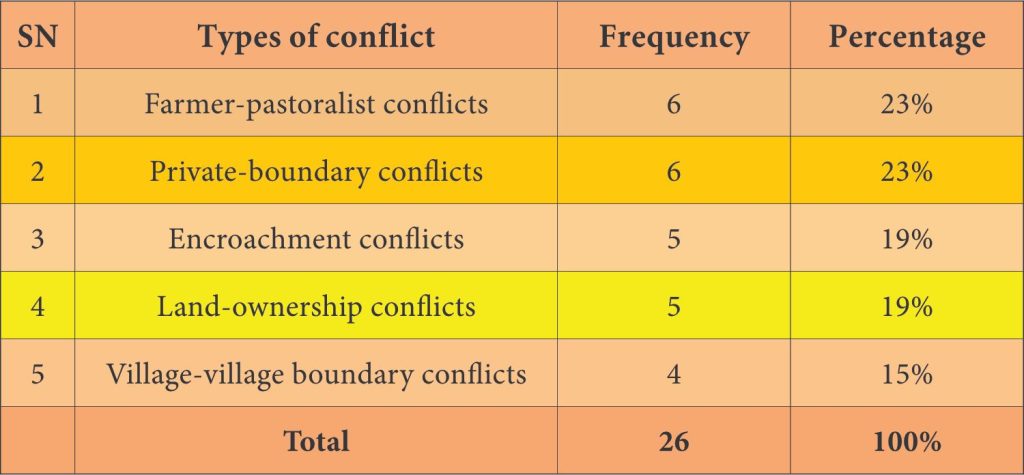

The findings presented in Table 1 are based on secondary data from reported cases, at the time of this study (June 2024) and the associated percentage of different types of conflicts. Additional statistics on conflict from 1990 to the time of the survey (June 2024) were compiled based on manual records at Mkindo Ward and are provided in Table 3. All this data suggests that private-boundary conflicts are the most common type of conflict, which account for 23% of the cases, along with farmer-pastoralist conflicts. This is followed by land-ownership conflicts and encroachment conflicts, each accounting for 19%. Village-village boundary conflicts are less common, making up 15% of the cases. Table 1 also displays the frequencies of various conflict-related codes obtained through interviews. Although the most common conflicts remain farmer-pastoralist and encroachment conflicts, there is a clear indication that new forms of conflict are emerging, namely destruction of crops by livestock and land scarcity.

Table 1: Themes on sources of conflict with their respective frequencies

Responses from the interviews revealed that unclear boundaries were among the causes of land disputes in the studied villages. According to a respondent from the Mvomero Land Department, unclear village boundaries frequently lead to conflicts between neighbouring villages or individuals over land ownership. Regarding boundary conflict, the respondent had this to say:

Unclear village boundaries resulted into a conflict between neighbouring villages or individuals regarding land ownership, leading to legal disputes and tensions within the community.

The findings in Table 2 show the thematic frequencies of the 10 coded themes based on the type of conflict. Based on these frequencies, it was revealed that people’s lack of awareness of village boundaries is also responsible for land conflicts. This cause of land conflict can be considered from two points of view, as explained by a senior respondent from the Land Department and VEO:

Sometimes boundary conflicts occur when the villagers do not know the exact boundaries of their villages … and most villagers who were born recently do not know the boundaries of their villages, despite their elders knowing those boundaries.

This implies that some villagers are not aware of their boundary marks, which leads to boundary conflicts. One of the interviewed VEOs stated:

All these boundary conflicts have been initiated and triggered by the absence of vivid and proper landmarks surveyed to show approved demarcation clearly … the villagers usually insist that leaders from the Land Department must come and show the boundary mark of our village so that we can be aware of our boundary.

Table 2: Types of land conflict

The absence of clear boundary marks leads to disputes, as supported by observations by Ringo, (2023), who suggests that educating villagers about their boundary marks and ensuring visible landmarks are crucial steps to prevent land conflicts. From an interview conducted with a land officer, it was revealed that at the village level there was a poor VLUP with a lack of demarcation and clear boundaries:

One of the reasons of [the] land conflicts’ persistence between Kambala and [the] neighbour[ing] village is that [the] chief of Kambala village refuses to enter in the village land use plan and surveying of their boundaries.

A closer scrutiny of the above extracts suggests that conflicts in the case study area result in tensions, not only among farmers and pastoralists but also between one village and another. This observation on the dominance of boundary conflicts confirms the findings by Benjaminsen et al. (2009) that unclear boundaries are among the major causes of land conflicts. It was further noted that Kambala village does not have a VLUP, an important institutional tool alongside institutional theory; thus, the lack of clear boundaries, an eminent recipe for conflicts. The interviews’ thematic analysis in Table 2 confirms that unclear boundaries are among the causes of land disputes in the studied villages. The demarcation of plots, anchored on well-functioning formal institutions as a tool for conflict resolution, has served a useful purpose in conflict resolution throughout Tanzania, (Alanga, 2019; Ntumva, 2023).

Population, markets and informality

From the marketing point of view, the information in Table 1 suggests that multiple sales or the rental of farms to more than one person due to the rapid increase in the population and the demand for land for agricultural activities, have also contributed to the escalation of conflicts. In this regard, one of the respondents suggested that “villagers [should] rent and sell their land for farming and ranching and remain with land that does not meet their needs”.This form of conflict is resolvable via principled negotiations, since it involves two parties willingly entering into an agreement. By focusing on the root cause, the buyer responds to their need for land, while the seller likely has other urgent problems and is thus in need of cash (Herman, 2020). Although these sellers agreed on the transaction willingly, they may realise their subsequent need for land and attempt to reclaim the sold land, which then gives rise to conflict. In an environment where contracts are duly respected, such conflict would not occur; but where contracts are informal and often incomplete, tensions of this nature are common and need redress via negotiation.

Additionally, the rapidly growing populations of people and livestock can exert pressure on essential resources like water, fertile land for crops and grazing, and building materials. This competition leads to tension and disputes between groups, particularly when traditional resource management practices break down, as articulated by one of the respondents from the village:

One of the causes of farmers’ and pastoralists’ conflicts is the rapid increase in [the] population of livestock and people [that] leads to [the] high demand of land for cultivation and grazing land.

This heightened scarcity of land leading to conflicts between farmers and pastoralists is in accord with observations by Wehrmann (2008), who suggests that educating farmers and pastoralists and providing guidance on sustainable land management practices can help mitigate conflicts.

Abandonment and encroachment consequences

In the case study areas, both encroachment and abandonment were found to be related to conflict escalation, as local people — both farmers and pastoralists — encroached on abandoned farmlands (Falanta and Bengesi, 2024). The abandonment of titled and untitled plantations was a notable cause of encroachment conflicts, not only between the real owners (often government) and the farmers or pastoralists but also among farmers and herders. Cases of abandonment and encroachment of farms and plantations in the study area have also been previously reported and investigated (see Massoi, 2021; Falanta and Bengesi, 2024). One of the interviewed village chairpersons said: “In many cases, the lack of maintenance and oversight on [an] abandoned plantation can attract opportunistic encroachers who may illegally occupy the land”.The most serious part is when the first invader is a farmer, and the herder is aware that the farmer has no legal rights. The herder may graze on crops claiming to have no idea that the abandoned land has been cultivated with crops.

Encroachment on abandoned land may also occur on private land, as one respondent from the Land Department indicated: “Some landowners who buy land in villages do not develop their land for so long, and when they return, they find their land taken by other people”. This implies that encroachment is caused primarily by the presence of undeveloped plots, whether by a private or a public entity. This finding is supported by Wehrmann (2015), who observes that those disputes arise when people decide to invade lands that have been left vacant by their original owners.

Power and authority in land conflicts

The misuse of a position of authority or influence for personal gain or to harm others was also noted as an important cause of land conflicts in the study area. This can be done in many ways, including, using threats or fear to control someone’s behaviour, pressuring someone to do something they do not want to do, using deception or trickery to get what you want and favouring friends or family members over qualified candidates. One of the respondents explained

The famers’ and pastoralists’ conflicts in Mvomero continue to escalate due to the abuse of power, since the pastoralists are favoured; because of their worth in large herds, they can offer bribery to proceeding the cases.

Conflict as a response to climate change

The interviews also elucidated on climate change as a significant factor in exacerbating conflicts between farmers and pastoralists. As climate change alters weather patterns, pastoralists often migrate southward in search of suitable pasture for their livestock. This movement triggers critical reactions among different groups, leading to tensions with farmers. According to one of the respondents:

The conflicts between farmers and pastoralists escalating — particularly during the dry seasons due to unpredictable weather patterns — affect vegetation, water availability and land quality. Both farmers and pastoralists compete for these scarce resources, intensifying conflicts.

Climate change disrupts agricultural cycles, thus affecting crop yields and livestock productivity. In turn, livelihoods are threatened, leading to heightened tensions.

6. Conflict outcome and resolution

Regarding the impacts associated with farmer-pastoralist conflicts, the observations from this study suggest that land conflicts have severely disrupted the peace and safety of local communities. This was a major concern expressed by almost every interviewee. The conflicts lead to violence, including burned homes, assaults, injuries and even deaths on both sides. One of respondents had this to say:

We’re not on good terms at the moment. They invaded our territory and attacked us with machetes! Thankfully, the government intervened and stopped the violence. Now that things have calmed down, we’re trying to rebuild our relationship.

There seems to be a fragile peace in place after a rough conflict. While the violence has ended, there are still underlying tensions that need to be addressed by both parties as they resume their interaction. Furthermore, the observations suggest that there is a lack of access to enough food for people living in the areas where the fighting happened. One of the respondents explained:

Some of us have been affected with hunger because they have been invading our farms and feed their livestock with our crops, sometimes when the cropping season is close to an end. Eventually, we become unable to grow new crops, a situation leaving us with nothing to rely on for food and other needs

Land conflicts have destabilised markets and transportation networks as well as land tenure security. Among the factors that contribute to land tenure insecurity in the area is unclear ownership when there is no clear legal documentation about who owns what land; resultantly, disputes easily arise. According to one of the respondents:

Land conflicts have led many people to be dispossessed of their land, unable to sell their land, rent it out and use it freely.

The findings from interviews also suggest that periodic clashes between farmers and herders worsened their relationship, especially during heightened tensions. One of the interviewed farmers said:

Currently, we do not have a good relationship with the pastoralists; only a state of enormity exists between us. For example, I cannot invite a pastoralist for a meal, as what I prepare comes from the farm, which he destroyed by feeding his livestock.

Moreover, conflicts between farmers and pastoralists were perceived to contribute to the stagnation of the broad context of economic growth in the district. Farmers view the existence of conflicts in their respective villages as one of the key hindrances for their full engagement in agricultural activities. For instance, a traditional leader from Mkindo village said:

To be honest, if, for example, your three hectares of crops have been destroyed while you were expecting them to feed you and give you other needs for two or more years, you become confused. These pastoralists halt our development. It is difficult to have any development. No matter how hard one tries to work, it is difficult to succeed under such circumstances.

This research further examines the different conflict-resolution methods employed in the study area. From the interview findings, it was revealed that one of the mechanisms used in addressing the conflicts is through negotiation. One respondent from the land council reported:

[The] advantage of negotiation is preserving [the] relationship, since it allows parties to find solutions while maintaining a positive working relationship. [It is] faster and less expensive than litigation, and both parties can feel satisfied with the solution.

By fostering communication and understanding alongside the principled negotiations theory, parties can find common ground and work towards mutually satisfactory outcomes. The benefits are preserving relationships, cost-effectiveness and satisfaction. In negotiations, once an amicable solution is found, one party can draft the resolution and submit it to the other for verification and signing. Alternatively, mediation was found to be useful, as supported by Haning et al. (2022), in this instance for land conflict resolution. One respondent elaborated:

The mediator helps the parties explore different options for resolving the conflict, and if a solution is found that is agreeable to both parties, the mediator helps formalise it in a written agreement.

By involving a neutral third party, mediation allows for open communication and exploration of various solutions. Wood (2017) concurs that when both parties find an agreeable resolution, the mediator helps formalise it through a written agreement. This process contributes to maintaining peace and harmony. Furthermore, the formal adjudication process was used by involving a neutral third party, often a judge or arbitrator. Regarding this approach, one of the interviewed local government officials explained:

Adjudication can be court-based adjudication, since this is the most common form, taking place in a courtroom with a judge presiding; or arbitration,a private form of adjudication where the parties choose a neutral arbitrator and agree to be bound by their decision. Arbitration can be faster and less expensive than court-based adjudication.

The findings revealed that the conflicts and the associated resolutions between farmers and pastoralists had some long-term consequences. As evidence of reconciliatory attempts, one of the respondents said:

While challenging, reconciliation is essential for building lasting peace and preventing future conflicts between farmers and pastoralists. By addressing the root causes of conflict, healing past wounds and promoting understanding, reconciliation can pave the way for a more just and peaceful future.

Regarding government intervention by using one or more of the above strategies, one of the respondents noted:

Paramilitary groups played an important role in reducing the conflict between farmers and herders. Typically, conflict resolution requires a variety of approaches and paramilitary groups can provide stability and prevent further unrest.

However, most government efforts are by their nature temporary and in most cases failed to provide a lasting solution due to significant power imbalance between farmers and pastoralists. The weaker group (farmers) often feels pressured to accept unfair solutions, since this approach is suited for short-term conflicts. An interview with the land officer at Mvomero District Council revealed that the local government interventions to address conflict in villages were constrained by several factors. These include the inadequacy of resources, low levels of knowledge and awareness on land matters, absence of the village land councils, lack of a VLUP — especially in pastoralist villages — and an absence of adequate and coordinated information. This invariably leads to the escalation of conflicts, as shown in Table 3.

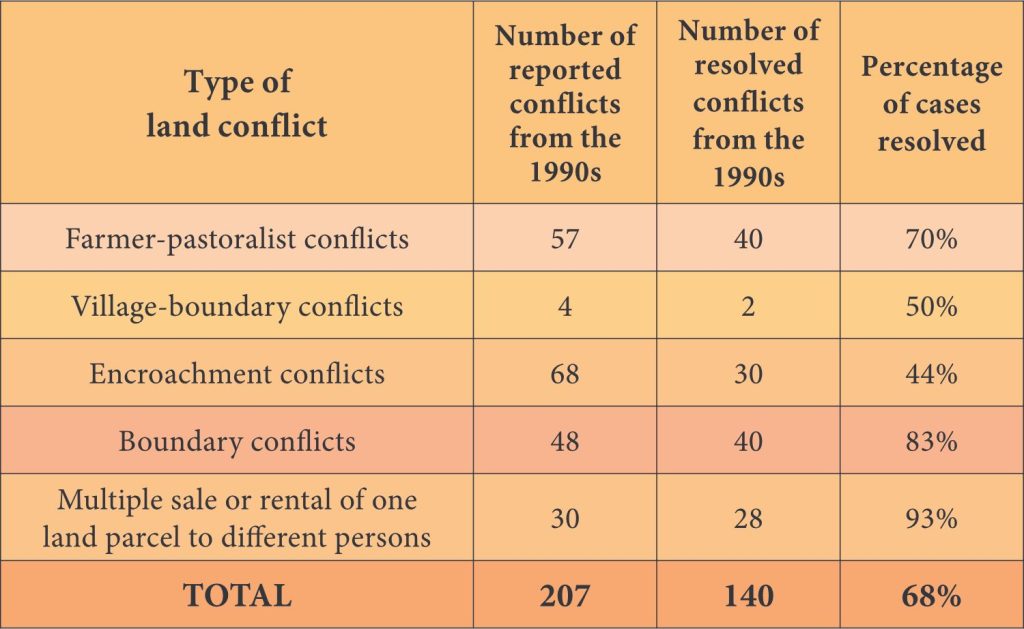

Table 3: Number of land-related conflicts reported and resolved in a ward tribunal

The results in Table 3 are based on manually recorded land conflict cases, as reported at ward level, where it was found that 140 of all reported cases (68%) were resolved, while 67 cases (32%) remained unresolved. This means that a significant majority of the conflicts reported were resolved successfully. This is a positive sign, suggesting that the existing conflict-resolution mechanisms are functioning, to some degree. Thus, despite the successes, there is still a noteworthy proportion of conflicts that remain unresolved at ward level.

Regarding the challenges in land conflict resolutions, the findings showed that the district land department has inadequate resources to sustain it in the resolution of the land disputes. This, in turn, led to the poor performance. For instance, financial resources and survey equipment, which are used during the resolution of land conflicts through real time kinematics (RTK), are not available. An interview with the land officer confirmed this:

The scarcity of resources is one of the challenges that hinder the effective management of land disputes at the village level and in the district in general.

He added that the lack of fuel and survey equipment such as RTK makes it impossible for the department of land to visit the villages.

The management of land disputes at village and district levels is difficult due to lack of necessary resources for effective executions, which is a recurring problem in many other land offices, as observed by Makupa and Alananga (2021). Further, the interviews with the land officer and the VEOs highlighted that at the village level, people are unaware of the land laws and the dispute-settlement organ. The land official interviewed stated:

Many villagers are unaware of land laws and dispute resolution procedures, thus leading to problems during dispute resolution. … [they] also sometimes use people called ‘bush lawyers’ to inform them about the procedure to follow in a dispute.

This finding suggests that there is a need to raise community awareness on land issues by conducting training and seminars on new land laws (Land Act No. 4 and Village Land Act No. 1999), which would increase community awareness on land issues and reduce land disputes among villagers. The interview with the land officer and the VEOs also revealed that in Mvomero there are no functional land councils such as ward tribunals, district land and housing tribunals as well as village land councils. Instead, all land dispute cases are reported and resolved under the district land department office. One land officer had this to say:

As in Mvomero District Council, we do not have village land councils; so, we, as the district land office, are obliged to receive and resolve such disputes that arise in the different villages … and if there are any disputes that hinder us, we submit them to the regional land office.

Similarly, from the findings it was learned that there is a lack of effective VLUPs, especially in village areas whereeby one of the studied villages namely Kambala, lack the VLUP completely and this makes it difficult for the district land department to solve land disputes, especially boundary disputes between villages. This is supported by the response of a land officer who said:

Many villages do not have land use plans, so sometimes it becomes difficult to know the exact boundaries of the villages … land use plans are important, since they will show clear boundaries and demarcate land for different uses and purposes.

This implies that most of the land disputes that occur in Mvomero District Council are due to a lack of an effective VLUP and the district land office fails to resolve such disputes because of an ineffective VLUP. Similarly, the lack of expertise and knowledge among ward land council members can be a significant challenge in the effective handling of land conflicts. One of the respondents, a council member, expressed these concerns:

We are struggling to understand complex land laws, leading to delays to unfair settlements. Also, many [of] the decisions made without a full understanding of the situation can have unintended consequences, potentially exacerbating conflicts.

The findings showed that without proper knowledge, council members may be susceptible to manipulation by parties with more knowledge of the legal system. This view is supported by Rubakula et al. (2019), who assert that the provision of regular training programmes on land laws, conflict-resolution techniques and mediation skills can significantly improve council members’ effectiveness.

7. Conclusion and recommendations

From the study, the most frequent land conflicts were related to encroachment, farmer-pastoralist disputes and private boundaries. Regarding the sources of these conflicts, the findings suggest that the four main causes are: abuse of power, which dominates as a cause (Falanta and Bengesi, 2024); limited awareness or understanding of village boundaries; unclear boundaries, which ranks third alongside Ringo’s (2023) insights; and limited land availability for agricultural or other purposes. Additionally, the abandonment of both titled and untitled farms is a critical cause of land conflict in the study area, consistent with the findings of Yohanes et al. (2024), who concluded that abandonment creates opportunities for conflicts over land use and claims.

Another critical concern is the lack of a VLUP, the absence of which has led to haphazard development and disputes over land use. Huggins (2016) concludes that effective planning is crucial for sustainable land management. A further cause is the destruction of agricultural land by livestock, which can lead to economic losses for farmers and subsequent conflicts. Benjaminsen et al. (2009) note that this issue often arises from inadequate fencing or poor livestock management, including overstocking.

The implications of farmer-pastoralist conflicts in Mvomero District are multifaceted, affecting various aspects of community life. One of the most significant impacts is the loss of peace and security. These conflicts have led to severe consequences, including the destruction of homes, incidences of rape, beatings, injuries and even deaths among both farmers and pastoralists (Boroş et al., 2010). This pervasive insecurity disrupts daily life and creates a hostile environment. The conflicts also contribute to food insecurity. Both farmers and pastoralists acknowledge the existence of food insecurity, but the perceptions on it differ significantly.

The conflicts also deepen the social divide between farmers and pastoralists (Falanta and Bengesi, 2024). The relationship between these groups continues to deteriorate, particularly during periods of high tension. Farmers often view pastoralists as aggressive and contemptuous, further worsening the divide (Ntumva, 2023). The conflicts contribute to stagnation in economic growth within the district, with farmers viewing the ongoing disputes as a major barrier to fully engaging in agricultural activities. This stagnation affects the broader economic context, limiting opportunities for development and prosperity (Benjaminsen et al., 2009). Displacement is another outcome, with violent conflicts often leading to the displacement of people from their homes. Pastoralist communities are frequently the most affected, enduring revenge attacks from farmers.

The findings on conflict resolution highlight deficiencies in the current approaches. The government prefers short-term coercive measures, relying on paramilitary forces and the police to suppress the conflicting parties. While this approach may be effective as a temporary measure, it does not address underlying grievances, and pastoralists are often removed from farms without any proposed remedy for the losses incurred. Furthermore, these methods are costly, with actors facing resource shortages such as money, fuel and survey equipment to sustain the resolution of disputes through coercive means. More effective approaches, such as negotiated solutions, are rarely employed, and when they are, there is a lack of knowledge and awareness about land matters at the village level. As a result, people are often unaware of land laws, which has led to some losing their land rights. This lack of awareness affects not only landowners but also leaders, who are mandated by law to oversee peace and tranquillity in the area and manage the land.

The findings showed that Mvomero District, specifically Kambala village, lacked any village land councils. As a result, land conflict cases accumulated at the wards and district land councils. Therefore, providing the district land office with the necessary resources could enhance its ability to respond to disputes by improving the mobility of officers and enabling the establishment of the required village land councils. Similarly, the availability of resources could facilitate the implementation of VLUPs in the remaining villages, clarifying boundaries and providing land deeds. In terms of land conflict resolution, it is evident that the key to successful negotiated solutions lies in understanding the differing interests of the parties involved, as well as their perceptions regarding the land in conflict. Thus, to ensure objectivity in the process, communities should be aware of land laws, regulations and the local context. Additionally, they should be familiar with negotiation, mediation and reconciliation techniques.

References

Ajayi, T.A. and Buhari, O.L. (2014) Methods of conflict resolution in African traditional society. African Research Review, 8 (2), pp. 138–157. Available from: <http://dx.doi.org/10.4314/afrrev.v8i2.9> [Accessed 29 February 2025].

Alananga, S.S. (2019) Practitioners’ perspectives on land resource conflicts and resolution in Tanzania. Journal of Rural and Community Development, 14 (2), pp. 87–106.

Barclay, C. (2018) Semi-structured interviews. Know How [Internet] Available from: <https://know.fife.scot/__data/assets/pdf_file/0028/177607/KnowHow-Semistructured-interviews.pdf [Accessed 20 May 2025].

Benjaminsen, T.A., Maganga, F.P. and Abdallah, J.M. (2009) The Kilosa killings: political ecology of a farmer-herder conflict in Tanzania. Development and Change, 40 (3), pp. 423–445.

Boroş, S., Meslec, N., Curşeu, P.L. and Emons, W. (2010) Struggles for cooperation: conflict resolution strategies in multicultural groups. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 25 (5), p. 539–554.

Burke, C. (2014) Overview of land conflict and identification of good practices in land conflict resolution, Uganda. United Nations [Internet] Available from: <https://www.undp.org/sites/g/files/zskgke326/files/migration/ug/Land-Conflict-Resolution-in-Acholi-Nov–2011.pdf> [Accessed 29 February 2025].

Easy Sociology. (2024) Understanding conflict theories in Sociology.[Internet]

Available from: <https://easysociology.com/sociological-perspectives/understanding-conflict-theories-in-sociology/> [Accessed 29th February 2025].

Edeh, H.O., Balana, B.B. and Mavrotas, G. (2022) Land tenure security and preferences to dispute resolution pathways among landholders in Nigeria. Land Use Policy, 119, p. 106179.

Enyindah, I.C. and Amugo, F.O. (2021) Land disputes between the Hausa/Fulani-Elele and Elele community, 1890–2006: lessons in intergroup relations in Nigeria. Niger Delta Journal of Gender, Peace & Conflict Studies,1 (3), pp. 375–384.

Falanta, M.E. and Bengesi, M.K. (2024) Drivers and consequences of recurrent conflicts between farmers and pastoralists in Kilosa and Mvomero districts, Tanzania. Journal of Sustainable Development, 11 (4), pp. 13–23.

Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO). (2006) Land tenure alternative conflict management.[Internet] Available from: <https://www.fao.org/docrep/pdf/009/a0557e/a0557e00.pdf> [Accessed 29 February 2025].

Francis, M., Sharissa, F. and Jurgen, P. (2017) Between policy intent and practice: negotiating access to land and other resources in Tanzania’s wildlife management areas. Tropical Conservation Science, 10, pp. 1–17.

Fratkin, E. (2014) Ethiopia’s pastoralist policies: development, displacement and resettlement. Nomadic People, 18 (1), pp. 94–114.

Garner, H.L. (2022) Understanding farmer-herder conflict between the Mossi and Fulani in Burkina Faso, using agent-based modelling (ABM).Honors thesis, Texas A&M University.

Haning, S., Kaesmetan, R.M. and Rema, A.D. (2022) The role of the village head as mediator in resolving land disputes. The International Journal of Social Sciences World, 4 (1), pp. 78–86.

Hasunga, F., Mohamed, F. and Awinia, C. (2022) The extent of women’s access to customary land titles in Mbozi district, in Songwe region, Tanzania. Business Excellence and Management, 12 (4), pp. 94–110.

Herman, G.M. (2020) Getting to yes: traditional theory. In: Herman, G.M. Settlement negotiation techniques in family law: a guide to improved tactics and resolution. American Bar Association (ABA) Book Publishing. pp. 1–6. Available from: <https://www.americanbar.org/content/dam/aba-cms-dotorg/products/inv/book/406633242/chap1-5130248.pdf> [Accessed 29 February 2025]

Huggins, C. (2016) Village land use planning and commercialization of land in Tanzania. Research Brief 01, Land Governance for Equitable and Sustainable Development, LANDac, Utrecht University, the Netherlands.

International Work Group for Indigenous Affairs (IWGIA). (2015) Ethnic violence in Morogoro region in Tanzania. Briefing Note.[Internet] Available from: <https://iwgia.org/images/publications/0714_Briefing_Note_Violence_in_Morogoro_Tanzania.pdf> [Accessed 29 February 2025].

Joynus, C. (2024) Interview with Bungoma Villager on 15 June. Bungoma Village Mvomero. [Cassette recording in possession of author].

Joynus, C. (2024) Interview with Kambala Village Executive Officer on 12 June. Kambala Village Mvomero. [Cassette recording in possession of author].

Joynus, C. (2024) Interview with Kambala Villager on 12 June. Kambala Village Mvomero. [Cassette recording in possession of author].

Joynus, C. (2024) Interview with Mkindo Village Executive Officer on 13 June. Mkindo Village Mvomero. [Cassette recording in possession of author].

Joynus, C. (2024) Interview with Mndela Villager on 15 June. Mndela Village Mvomero. [Cassette recording in possession of author].

Joynus, C. (2024) Interview with Mvomero Land Officer on 18 June. Mvomero. [Cassette recording in possession of author].

Kraft, M.E. and Furlong, S.R. (2019) Public policy: politics, analysis and alternatives. Sage Publications.

Krislov, J. (1987) Review: C.W. Moore (1986) The mediation process: practical strategies for resolving conflict, San Francisco, Jossey-Bass. Industrial and Labor Relations Review, 40 (2), p. 291–292.

Makupa, E. and Alananga, S. (2021) Understanding resource constraints in land administration in Dodoma, Tanzania. The Journal of Building and Land Development, 21 (1), pp. 64–80. [Internet] Available from: <http://journals.aru.ac.tz/index.php/JBLD/article/view/273> [Accessed 29 February 2025]

Massay, G.E. (2017) In search of the solution to farmer-pastoralist conflicts in Tanzania. Occasional paper No. 257, South African Institute of International Affairs (SAIIA).

Massoi, L.W. (2015) Land conflicts and the livelihood of pastoral Maasai women in Kilosa District of Morogoro, Tanzania. Afrika Focus, 28 (2), pp. 107–120.

Mohamed, A. (2015) Underlying causes of inter-ethnic conflict in Tana River County, Kenya. Master’s thesis, University of Manitoba.

Moore, C.W. (2012) The mediation process: practical strategies for resolving conflict. 4th ed. San Francisco, Jossey-Bass.

Mung’ong’o, C. and Mwamfupe, D. (2003) Poverty and changing livelihoods of migrant Maasai pastoralists in Morogoro and Kilosa Districts, Tanzania. Mkuki na Nyota Publishers, Dar es Salaam

Mwamfupe, D. (2015) Persistence of farmer-herder conflicts in Tanzania. International Journal of Scientific and Research Publications, 5 (2), pp. 1–8.

Ntumva, M.E. (2020) Farmer-pastoralist conflicts in Kilosa District of Tanzania: a qualitative study of stakeholder perspectives on causes, impacts and responses. PhD thesis, University of Bradford.

Ntumva, M.E. (2023) Understanding dynamics of farmer-pastoralist conflicts in Tanzania: insights from Kilosa District case study. International Journal of Agricultural Extension, 11 (3), pp. 225–241.

Nwokafor, L.C., Obasi, C.O. and Ejinwa, E. (2020) Land encroachment and banditry as emergent trends in communal and inter-ethnic conflicts in Nigeria. Journal of Community and Communication Research, 5 (1), p. 144–151.

Prayogi, A. (2023) Social change in conflict theory: a descriptive study. ARRUS Journal of Social Sciences and Humanities, 3 (1), pp. 37–42.

Ringo, J. (2023) Roles of village land councils in mitigation of land conflicts in Ngorongoro district, Tanzania. Heliyon, 9 (4), p. e15132.

Rubakula, G., Wang, Z. and Wei, C. (2019) Land conflict management through the implementation of the national land policy in Tanzania: Evidence from Kigoma region. Sustainability, 11 (22), p. 6315.

Sackey, G. (2010) Investigating justice systems in land conflict resolution: a case study of Kinondoni Municipality, Tanzania. Master’s thesis, University of Twente.

Saruni, P.O., Kajembe, G.C. and Urasa, J.K. (2018) Forms and drivers of conflicts between farmers and pastoralists in Kilosa and Kiteto districts, Tanzania. Journal of Agricultural Science and Technology, 8 (6), pp. 333–349.

Shemdoe, R. and Mwanyoka, I. (2015) Natural resources based conflicts and their gender impacts in the selected farming and pastoral communities in Tanzania. International Journal of African and Asian Studies, 15, pp. 83–87.

Stanton, R.A., Fletcher Jr R. J., Sibiya, M., Monadjem, A and McCleery R. A. (2021) The effects of shrub encroachment on bird occupancy vary with land use in an African savanna. Animal Conservation, 24 (2), pp. 194–205.

Stosch, K. C., Quilliam, R. S., Bunnefeld, N. and Oliver, D. M. (2022) Catchment-Scale Participatory Mapping Identifies Stakeholder Perceptions of Land and Water Management Conflicts. Land, 11(2).

Wehrmann, B. (2015) Land conflicts: a practical guide to dealing with land disputes. Eschborn, Germany, GTZ.

Wehrmann, B. (2017) Understanding, preventing and solving land conflicts: a practical guide and toolbox. Eschborn, Germany, GIZ.

Wood, J.F. (2017) Review: C.W. Moore (2014) The mediation process: practical strategies for resolving conflict, 4th ed., San Francisco, Jossey-Bass. Mediation Theory and Practice, 2.1, pp. 84–88.

Yamano, T. a. D. K., (2005) Land conflicts in Kenya: Causes, Impacts and Resolutions. [Internet] Available at: <https://www.researchgate.net/publication/228975980_Land_conflicts_in_Kenya_causes_impacts_and_resolutions> [Accessed 29 February 2025].

Yohanes, S., Leo, R.P. and Bunga, G.A. (2024) Reevaluation of non-assertive attitude of government officials as a criminologic factor in state land encroachment and environmental destruction in Kupang. Journal of Law and Sustainable Development, 12 (1), p. e2771.