Abstract

Lesotho’s protracted history of political instability and authoritarian governance between 1970 and 1992 has entrenched a culture of violence, the effects of which continue to undermine peacebuilding efforts under the current democratic dispensation (1993–2025). The novelty of this paper lies in its illustration of the utility of transitional justice in situations of political instability that are not characterised by large-scale civil wars or violence. The paper argues that sustainable peace and reconciliation require institutionalising a robust, context-sensitive transitional justice framework aligned with the African Union Transitional Justice Policy (AUTJP). Drawing on qualitative analysis of historical records and expert interviews of purposively sampled experts between 2024 and 2025 by the Lesotho Council of Non-Governmental Organisations and the Strategic Institute for Research and Dialogue, the study identifies a lack of coordinated, victim-centred justice responses to past human rights violations. The AUTJP offers a strategic blueprint for embedding transitional justice into Lesotho’s ongoing governance reforms. The study finds that combining retributive, restorative and redistributive justice approaches – while rooted in local traditions – can help address structural grievances and enhance the legitimacy of the reforms. Ultimately, the paper makes the case for adopting a legally grounded, nationally owned and participatory transitional justice policy informed by African and international best practices.

1. Introduction

Lesotho’s post-independence trajectory has been marred by cycles of political instability and an entrenched culture of violence rooted in its authoritarian past. Both civilian autocracy (1970–1986) and military rule (1986–1992) inflicted serious human rights violations, the effects of which remain visible despite more than three decades of democratic governance (Kapa, 2017; Matlosa, 2020; Kali, 2022). The failure of successive governments to address these historical injustices has undermined peacebuilding efforts and weakened the foundation for sustainable democracy. The novelty of this paper lies in its illustration of the utility of transitional justice in situations of political instability that are not characterised by large-scale civil wars and violence.

While Lesotho transitioned to multiparty democracy in 1993, the persistence of political violence, impunity and institutional fragility highlights the need for a more comprehensive approach to transitional justice. The African Union’s 2019 Transitional Justice Policy (AUTJP) provides a strategic framework that member states, such as Lesotho, can adapt to address the legacies of violence, build national unity, and promote inclusive reconciliation.

This paper contributes to ongoing national and continental debates by examining how Lesotho can institutionalise a contextually grounded transitional justice system aligned with the AUTJP. It builds a case for moving beyond ad hoc responses, such as commissions of inquiry or short-lived reforms, towards sustained, legally grounded and victim-centred transitional justice mechanisms. In doing so, it highlights the importance of adapting transitional justice to the country’s socio-political realities and historical wounds.

The analysis is informed by normative models of justice that underpin the AUTJP, including retributive justice (holding perpetrators accountable), restorative justice (repairing social relations) and redistributive justice (addressing structural inequalities). These justice models are used later in the paper to interpret Lesotho’s transitional justice gaps and to guide recommendations for building inclusive and durable peace. The paper argues that combining these justice approaches within a nationally owned framework, while drawing on African traditions and participatory processes, offers Lesotho its best chance at sustainable reconciliation and transformation.

Including these introductory remarks, the article is divided into eight sections. Section two introduces the methodology used to undertake this study. Section three presents the conceptual framework of justice in transitional contexts as a frame of analysis. Section four situates the discussion within the overall historical context. The fifth section sketches the periodisation of violence and human rights violations between 1966 and 2025. Section six addresses the rationale for transitional justice and the applicability of the AUTJP in Lesotho. The seventh section synthesises key findings of the study. The final section concludes the discussion and proffers six key recommendations.

2. Methodology

This paper is mainly qualitative and combines two complementary strands. First, the authors employ a historical-analytical map of political violence across six phases, aligned with regime type and signature incidents, to trace patterns of violation and institutional responses. Second, the authors conduct a cross-sectional survey (January–March 2025) to gauge the awareness of the AUTJP’s eleven pillars among key informants.

The authors purposefully selected experts who were influential actors in human rights and governance (government and oversight bodies, civil society organisations (CSOs), media, legal and security sectors, faith/traditional leaders, and think tanks) for inclusion in the study. Structured questionnaires with informed consent promising anonymity and stating that participation was voluntary were emailed to respondents. In total, 102 questionnaires were distributed, and 43 were completed (42.2%). The questionnaire assessed respondents’ familiarity with the AUTJP.

Analysis proceeded on two tracks. For the historical strand, documentary sources were synthesised using thematic analysis to identify recurring violation types and associated regime types as well as institutional responses in each phase. For the survey, descriptive statistics in the form of frequencies were employed to summarise overall awareness. The authors’ experience and observations of some historical events contributed to triangulating the thematic historical synthesis, enhancing credibility and informing conclusions. The paper acknowledges the limitations of non-probability sampling and potential non-response bias; therefore, no generalisations are made.

3. Conceptual framing

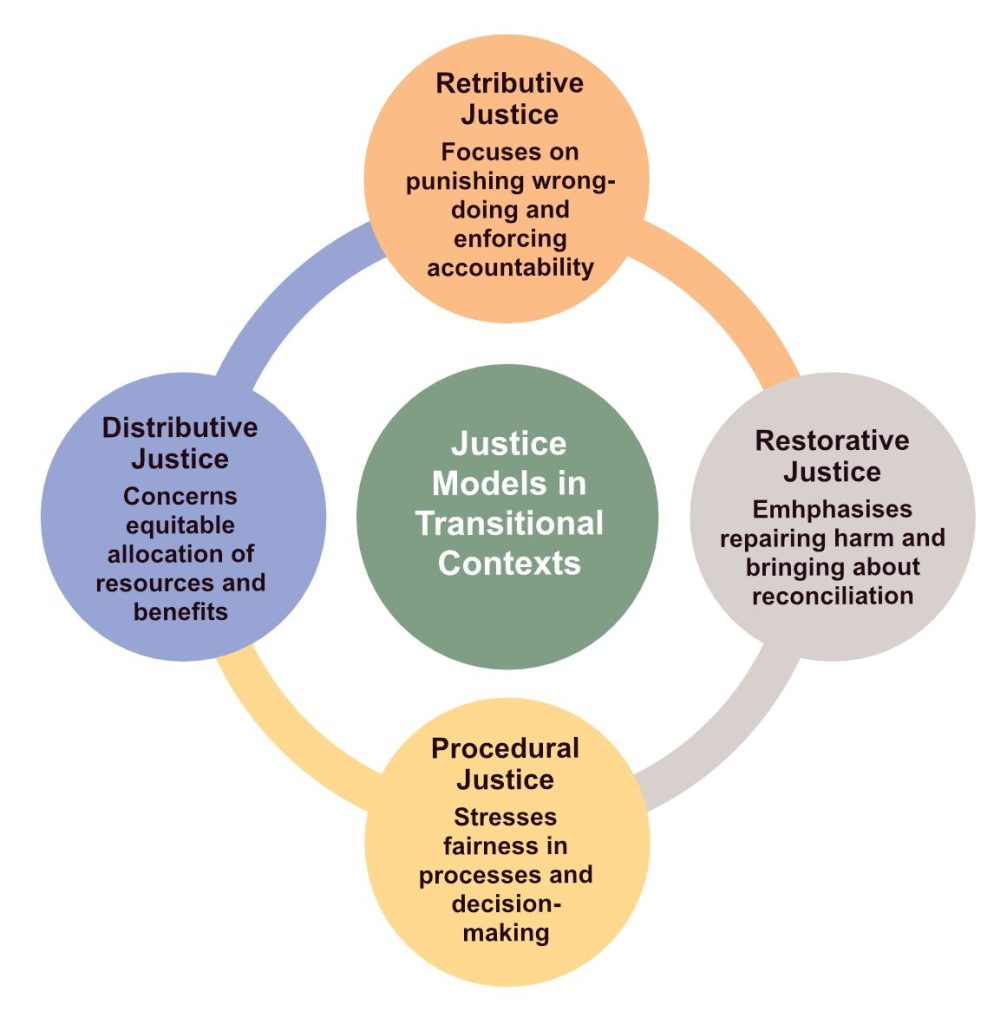

Transitional justice processes are underpinned by various conceptions of justice that reflect the moral, legal and political imperatives of societies emerging from conflict or authoritarian rule. Among the most influential models are retributive justice, restorative justice, distributive (or redistributive) justice and procedural justice. Retributive justice, rooted in classical legal theory, emphasises punishment for wrongdoing and the moral imperative of accountability. It is often associated with thinkers like Immanuel Kant (1996), who argued that justice requires perpetrators to be punished proportionally to their crimes. In transitional contexts, retributive justice is operationalised through trials, prosecutions and special tribunals aimed at ending impunity and deterring future abuses.

Restorative justice, by contrast, prioritises repairing the harm caused to individuals and communities. Championed by theorists such as John Braithwaite (2002), it promotes dialogue, truth-telling, forgiveness and reconciliation between victims and perpetrators. This model is particularly salient in African contexts where communalism and relational ethics often take precedence over individual culpability. Restorative justice mechanisms, such as truth commissions and community reconciliation processes, emphasise healing and reintegration over punishment. In Lesotho, with its deep cultural reliance on traditional conflict resolution and mediation led by chiefs and elders, restorative justice resonates strongly as a culturally grounded and socially cohesive approach to redress.

Distributive or redistributive justice, as articulated by scholars such as John Rawls (1971) and Amartya Sen (2009), addresses the structural inequalities that underpin social and political conflicts. It calls for equitable access to social goods such as land, employment, education and services. In the AUTJP, redistributive justice is recognised as a foundational pillar, linking transitional justice to inclusive development and socio-economic transformation. For Lesotho, which continues to struggle with entrenched poverty, unemployment, inequality and marginalisation, redistributive justice is not merely complementary but essential to any viable transitional justice framework. This paper draws from these justice models (also summarised in Figure 1) to argue that a holistic approach, one that balances accountability, healing and socio-economic redress, is necessary for institutionalising transitional justice in Lesotho.

Figure 1: Common justice models

Source: Authors’ compilation

4. Historical context

Lesotho has embarked on a comprehensive national reform process aimed primarily at addressing the pervasive violent conflicts, instability, and insecurity. The immediate trigger for the reforms was the 2014–2015 political crisis that led to the Southern African Development Community (SADC) deploying the SADC Observer Mission in Lesotho (SOMILE) between September 2014 and November 2017. In its final report, SOMILE recommended, among others, comprehensive governance reforms for Lesotho (Pherudi, 2023).

In the government’s 2017 framing document, it made a firm commitment to “undertake far-reaching reforms to ensure stability and prosperity. Basotho deserve to live in a stable, peaceful and secure environment and be assured of the enjoyments of their rights and efficient service delivery” (Government of Lesotho, 2017:4). The reform process has received enormous political, technical and financial support from SADC, the Commonwealth Secretariat, the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), the European Union (EU) and the African Union (AU).

Since 2019, Lesotho has embarked on a comprehensive governance reform journey encompassing seven thematic areas: constitution, parliament, security sector, justice sector, public service, economy, and media. The Multi-Stakeholder National Dialogue (MSND) Plenary II Report details the form and substance as well as the execution of these envisaged reforms (Government of Lesotho, 2019a:47). Additionally, peacebuilding is part and parcel of this reform agenda, specifically the institutionalisation of transitional and other justice processes. The National Reforms Authority (NRA) was established through an Act of Parliament to coordinate the implementation of this seven-pronged reform agenda. Notably, the NRA was also tasked with implementing peacebuilding and transitional justice mechanisms aimed at preventing, managing, and resolving conflicts, which are necessary for the country’s durable stability (Government of Lesotho, 2019b).

Transitional justice is often a propitious policy response in countries engulfed in pervasive violent conflicts, either transitioning from autocracy to democracy or from war to peace. Postcolonial Lesotho has been entangled in protracted violent conflicts. Although contemporary Lesotho has been spared the vagaries of a full-blown and outright war, it has been historically bedevilled by an embedded culture of violence, as illustrated in Table 1.

Table 1: Historical trajectory of the culture of violence in Lesotho

| Period | Governance Type | Regime Type | Magnitude of Violence and Human Rights Violations |

| 1966–1970 | Embryonic multiparty | Democratic | Covert and sporadic* |

| 1971–1985 | One party | Authoritarian | Overt and generalised** |

| 1986–1992 | Military | Authoritarian | Overt and generalised |

| 1993–2001 | Fragile multiparty | Democratic | Covert and sporadic |

| 2002–2011 | Dominant party | Democratic | Covert and sporadic |

| 2012 to date | Coalition | Democratic | Covert and sporadic |

* Denotes that the culture of violence was relatively less profound, and the magnitude of human rights violations was relatively low. This was the case under democratic regimes.

** Denotes that the culture of violence was relatively more profound, and the magnitude of human rights violations was relatively high. This was the case under authoritarian regimes of both civilian and military varieties.

Source: Authors’ compilation from Aerni-Flessner et al. (2025)

As illustrated in Table 1, from 1966 to the present, post-independence Lesotho has been characterised by various types and magnitudes of violent conflicts, as detailed in the next section. The incessant violent conflicts generate political instability, insecurity and socio-economic uncertainty. This violence, to a considerable extent, accounts for the country’s current poor development prospects and its overwhelming dependency on external economic factors (i.e., aid, trade, and foreign direct investment). This creates a vicious cycle or conundrum for Lesotho because violence is not only costly socio-economically and politically, but it also severely threatens these three external resource flows into the country.

5. Periodisation of violence, 1966–2025

The culture of violence can be disaggregated into six distinct, albeit intertwined, historical phases, namely, phase 1: 1966–1970; phase 2: 1971–1985; phase 3: 1986–1992; phase 4: 1993–2001; phase 5: 2002–2011; and phase 6: 2012–2025 (Matlosa, 1999). These phases are discussed below, with illustrative tables. The analysis shows that while violence and human rights violations have become embedded throughout these phases, there is no evidence of efforts invested in peace-building and transitional justice during the eras of civilian (1966–1985) and military (1986–1992) autocracy. Some efforts were invested towards inculcating a culture of peace through, inter alia, transitional justice mechanisms, albeit with minimal results, since the transition to the current democratic era (1993–2025).

Phase 1: 1966–1970 – Embryonic democracy

As Table 2 shows, a trend towards a culture of violence in Lesotho was already evident during the period from 1966 to 1970. A year before being granted its political freedom from British colonial rule, Lesotho held its pre-independence elections in 1965, won by the Basutoland National Party (BNP). Seeds of political contention were sown, especially later in 1970, when the BNP annulled elections and declared a state of emergency (Matlosa, 1999). It was therefore no surprise that immediately upon its independence on 4 October 1966, in November of the same year, the then Police Mobile Unit (PMU) killed 11 people who were part of an anti-government protest that took place in Thaba-Bosiu in the Maseru District (Thabane, 2017).

During this period, the most significant and most violent events were witnessed, both before and in the aftermath of the 1970 general election, which the opposition BCP won. However, the then-ruling BNP annulled the process midstream, usurped power, declared a state of emergency, suspended the constitution, and institutionalised a de facto one-party rule, forcing King Moshoeshoe II into exile in the Netherlands (Monyake, 2020; Kali, 2022). There were no transitional justice mechanisms in place to address human rights violations during this period, as depicted in Table 2.

Table 2: Violence trends, 1966–1970

| Year | Events | Violence and Human Rights Violations | Transitional Justice Response |

| 1966 | Independence from Britain; anti-government protests at Thaba-Bosiu | Police kill 11 protestors at Thaba-Bosiu | None |

| 1970 | -General election held; opposition BCP wins.-BNP leader and Prime Minister, Leabua Jonathan, forces King Moshoeshoe II into exile in the Netherlands for opposing his usurpation of power | -Ruling BNP annuls results and usurps state power by force of arms.-BNP consolidates autocratic rule | None |

Source: Authors’ compilation from Khaketla (1972); Matlosa (1999); Monyake (2020); Kali (2022)

Phase 2: 1971–1985 – Civilian authoritarianism

It was during this period, from 1971 to 1985, that the BNP consolidated its one-party rule, anchored on repression and human rights violations (Khaketla, 1972; Aerni-Flessner et al., 2025). BCP’s armed wing, the Lesotho Liberation Army (LLA), began its military incursions into Lesotho aimed at dislodging the BNP government, ostensibly with the support of the apartheid state of South Africa.

It was during this period that the apartheid government undertook a military raid into Maseru in 1982, killing 42 people, of whom 30 were South African refugees and 12 were Basotho (Bardill and Cobbe, 1985; ANC, 2023). This raid was part of the racist regime’s deliberate regional policy of destabilisation against neighbouring countries that supported the liberation struggle in South Africa, which was pioneered mainly by the African National Congress (ANC) and the Pan-Africanist Congress (PAC).

The apartheid regime imposed a border blockade against Lesotho in 1985 as punishment for the BNP government’s refusal to deport South African refugees and sign the Highlands Water Treaty (SAHO, 2011). The blockade was accompanied by another military raid that killed nine people (ANC, 2023). Table 3 below illustrates episodes of violence and human rights violations. It also indicates that no transitional justice mechanisms were established to address human rights violations during this period.

Table 3: Violence trends, 1971–1985

| Year | Events | Violence and Human Rights Violations | Transitional Justice Response |

| 1971 | BNP’s consolidation of its one-party rule | LLA emerges as the armed wing of BCP, waging guerrilla warfare against the BNP government | None |

| 1982 | South African Defence Force (SADF) military raid | 42 people killed: 30 South African refugees and 12 Basotho nationals | None |

| 1985 | Border blockade; SADF military raid | 9 people killed | None |

Source: Authors’ compilation from Bardill and Cobbe (1985); Amnesty International (1992); ANC (2023)

Phase 3: 1986–1992 – Military autocracy

The era of one-party authoritarian rule under the BNP was replaced by military authoritarianism from 1986 to 1992. During this period, political activities were prohibited, and political parties were banned. The military had usurped power with the assistance of the South African apartheid regime (Monyane, 2009; SAHO, 2011). This period also witnessed the assassination of two prominent BNP leaders and former cabinet ministers, Desmond Themba Sixishe and Montŝi Vincent Makhele, together with their wives. During this incident, Mr Tŝolo Lelala and his wife survived the gruesome ordeal but were obviously extremely traumatised (Machobane, 2001:108–112).

Because of the apartheid influence, the military regime immediately deported the South African refugees from Lesotho and signed the Lesotho Highlands Water Treaty. The military consolidated its power, and tensions with King Moshoeshoe II began to mount. Consequently, as Leabua Jonathan did in 1970, in 1990, Major General Justin Lekhanya, Chairman of the Military Council, forced the King into exile, this time to the United Kingdom (UK), leading to Mohato Seeiso, the King’s elder son, ascending to the throne as King Letsie III. Under the military regime, violence and human rights violations remained the norm, as was the case under the BNP rule. Ultimately, as the democratisation waves swept across the globe and the African continent in the early 1990s, a reformist faction within the military junta, led by Phisoane Ramaema, took power, displacing the faction led by Metsing Lekhanya (Monyane, 2009; Amnesty International, 1992). This facilitated a process of transition to democracy through the establishment of the National Constituent Assembly, which reviewed the 1966 constitution as part of preparations for the 1993 transitional elections. The two main transitional justice processes that marked this period were the prosecution of soldiers responsible for the assassination of Makhele and Sixishe and their wives, the attempted murder of Lelala and his wife and the choreographed inquest into the killing of George Ramone by Metsing Lekhanya. Table 4 below illustrates some of the key events that marked the trend of violence and human rights violations, with limited success of transitional justice mechanisms.

Table 4: Violence trends, 1986–1992

| Year | Events | Violence and Human Rights Violations | Transitional Justice Response |

| 1986 | -Military coup.-Desmond Sixishe and Montŝi Vincent Makhele and their wives were assassinated, and Tŝolo Lelala and his wife survived. | -Banning of political parties; rule by decree.-Repression of civil liberties and political rights | -None-Prosecution and imprisonment of soldiers who committed the crime, including Sekhobe Joshua Letsie, a member of the Military Council |

| 1988 | Metsing Lekhanya, Chairman of the Military Council, shoots George Ramone, a student at the Agricultural College. | Repression of civil liberties and political rights | Inquest clears Lekhanya of wrongdoing |

| 1990 | -Mutiny and arrest of some soldiers, senior officers and members of the Military Council -Military junta forces King Moshoeshoe II into exile in the UK; King Letsie III acts as king | -Repression of civil liberties and political rights-Human rights abuses persist | None |

| 1991 | Phisoane Ramaema replaces Metsing Lekhanya as Chairman of the Military Council. | Ramaema reverses some of the repressive measures of the military junta | None |

| 1992 | Establishment of the National Constituent Assembly | Review of the 1966 constitution | Transition process |

Source: Authors’ compilation from Amnesty International (1992); Matlosa (1999); Kali (2022)

Phase 4: 1993–2001 – Fragile multiparty democracy

The transition from military rule to the current multiparty democracy was midwifed by the 1993 general election in which the BCP won all 65 seats. The result of the 1993 general election was widely deemed as ‘the righting of the wrong of 1970’. The optimism that greeted the election and the BCP victory soon gave way to despair and pessimism as political instability unfolded. The tension between the BCP government and the then-exiled King Moshoeshoe II prompted King Letsie III to topple the BCP government and establish a six-person state council. This development was reversed through a SADC mediation, involving heads of state Ketumile Masire of Botswana, Nelson Mandela of South Africa and Robert Mugabe of Zimbabwe. The three SADC leaders facilitated the signing of a Memorandum of Understanding that granted King Letsie III indemnity, restored the BCP government, and reinstated King Moshoeshoe II to the throne on 25 January 1995. In 1997, the ruling BCP suffered a major split due to leadership squabbles and intra-party factional conflicts, which led to the emergence of the Lesotho Congress for Democracy (LCD) under the leadership of then-BCP leader and Prime Minister, Ntsu Mokhehle. The LCD became the government in parliament, dislodging the BCP, which was pushed into the opposition corner, generating an enormous amount of political bitterness. It was no surprise, therefore, that when the LCD won the 1998 general election with a landslide victory, the BCP and the BNP (historically strange bedfellows and unlikely political allies) ironically joined forces to protest the election outcome. A commission of inquiry into the electoral process and legitimacy of the result was instituted and led by Justice Pius Langa of South Africa (U.S. Department of State, 1999). In 1999, another commission of inquiry led by Justice Jan Steyn, a South African judge, investigated the post-election violence. While the findings of the Langa Commission were ambiguous and therefore fuelled further political tension and conflict, those of the Steyn Commission identified those responsible for the violence and disturbances, paving the way for appropriate accountability (Amnesty International, 1992; Matlosa, 1999; Likoti, 2007; Monyake, 2020).

The BCP and the BNP organised protest marches. They mobilised their supporters to camp outside the gates of the Royal Palace in Maseru to mount pressure on King Letsie III to intervene. A military mutiny in 1998 worsened the instability and accentuated the violence. In 1998, eager to protect the Lesotho Highlands Water Project (LHWP) – South Africa’s primary source of water, especially for the Gauteng region – South Africa deployed the South African National Defence Force (SANDF) to the project site in Thaba-Tseka, where it launched a military raid on the Lesotho Defence Force (LDF) outpost guarding the project. This raid resulted in the killing of at least 11-16 LDF soldiers (Pherudi, 2003). This was part of Operation Boleas, which also involved SANDF military raids in Maseru, especially targeting the LDF military barracks, where further deaths were recorded. It is worth noting that Botswana also deployed the Botswana Defence Force (BDF), and together with the SANDF, this combined force constituted a SADC intervention force in Lesotho (Likoti, 2007).

As Lesotho stakeholders sought to identify the drivers and causes of political instability, they concluded that part of the problem lay with the winner-take-all first-past-the-post (FPTP) electoral model. The 12-party Interim Political Authority (IPA), led by opposition leaders Lekhetho Rakuoane (Popular Front for Democracy [PFD]) and Bereng Sekhonyana (BNP), was established to look into the model; this work was undertaken between 1999 and 2001. The result was the transformation of the FPTP electoral model into the current Mixed Member Proportional (MMP) electoral model, which has been in force since the 2002 general election. Major transitional justice initiatives during this period included: (a) the SADC mediation that restored the BCP government; (b) the Langa Commission of Inquiry into the 1998 elections; (c) the Steyn Commission of Inquiry into the violence that followed the 1998 elections; (d) compensation of about M250,000 paid by the government to each of the families of the 16 soldiers killed by the SANDF; and (e) the establishment of the SADC regional guarantors of Lesotho democracy comprising Masire (Botswana), Mandela (South Africa), Mugabe (Zimbabwe) and as from 1995, Joachim Chissano (Mozambique) (Likoti, 2007). Table 5 shows that during this period, the dominant method of transitional justice in response to violence comprised national dialogue fora, commissions of inquiry and mediation.

Table 5: Violence trends, 1993–2001

| Year | Events | Violence and Human Rights Violations | Transitional Justice Response |

| 1993 | Transition from military rule to multiparty rule; BCP wins the elections | Restoration of civil liberties and political rights | Transition to democracy |

| 1994 | Military mutiny; police strikes; political protests; King Letsie III topples the BCP government. | Political violence | SADC mediation, Khoarai Commission |

| 1995 | King Moshoeshoe II returns from exile in London; King Letsie III steps down. | Political violence | Restoration of the King’s position |

| 1997 | Ruling BCP splits following factional conflict; LCD is formed as a breakaway party; LCD replaces BCP as the government in parliament; BCP becomes the opposition party. | Political violence | None |

| 1998 | -Post-election crisis; military mutiny-SANDF military intervention, LHWP, Thaba-Tseka | Political violence | – Langa and Steyn Commissions- Compensation of victims of 16 LDF soldiers by the South African government through the Lesotho government |

| 1999 | Consultations and dialogue for electoral reforms | Political violence | IPA is established, and the FPTP electoral model is changed to the MMP model |

Source: Authors’ compilation from Fox and Southall (2003); Likoti (2007)

Phase 5: 2002–2011 – Dominant party system

During the period from 2002 to 2011, the only peaceful election that did not trigger post-election violence was the 2002 poll. It was the first election since the shift from the FPTP to the MMP model. The new model broadened the representation of political parties in parliament. The political system experienced relative stability, albeit for a short period. Despite the new electoral model (perhaps because of it), the 2007 election was marked by violent post-election conflict, which led to SADC deploying Sir Ketumile Masire of Botswana as the key mediator to settle the election-related disputes (Fox and Southall, 2003; Likoti, 2007). The prominent bone of contention centred on the manipulation of the electoral model by the two major parties, namely the LCD and the All-Basotho Convention (ABC). The result of this manipulation distorted the election results in their favour. The ensuing political instability led to further electoral reforms, which were undertaken in 2011. Table 6 below illustrates that the dominant mode of pursuing transitional justice during the period revolved around mediation and electoral reforms.

Table 6: Violence trends, 2002–2011

| Year | Events | Violence and Human Rights Violations | Transitional Justice Response |

| 2002 | General election under the new MMP electoral model | No political violence | None |

| 2007 | General election | Post-election violence | SADC mediation (Ketumile Masire of Botswana) |

| 2008 | Electoral disputes | Political tension | Electoral reforms |

Source: Authors’ compilation from Thabane (2017); Aerni-Flessner et al. (2025)

Phase 6: 2012–2025 – Coalition governance

The 2012–2025 period was marked by political instability stemming from the deeply ingrained and persistent culture of political violence, as well as the mismanagement of coalition governance. During this period alone, the country held four elections (2012, 2015, 2017, 2022). In the same period, Lesotho had four coalition governments. Between 2012 and 2017, three elections were held, and two coalition governments collapsed (Deleglise, 2018; Kali, 2022).

There has been persistent instability within the security sector, resulting in: abortive military coups; assassination of two army commanders by the LDF soldiers; flight of some LDF soldiers into exile in South Africa; arrest of the former LDF commander and senior officers; assassination of senior police officers; assassination of Lipolelo Thabane, the wife of Motsoahae Thomas Thabane, the former prime minister and serious injury of her close friend, Thato Sibolla; sexual and gender-based violence (SGBV); intensification of famo music gang-related violence –conflicts between and among groups of Basotho migrant workers in the South African mines, known for their traditional music and wearing of blankets, with colours distinguishing the gangs, armed with fighting sticks and other weapons; and Manomoro youth gangsterism – gangs of unemployed youth who survive through crime and violence, especially in urban (especially Maseru) and peri-urban areas, such as Motimposo, a tendency they essentially acquired in prison.

Since 2012 (at least until 2022), no single coalition government has lasted for more than two years in power (Deleglise, 2018). The current coalition is the exception to this rule, having survived the usual political turbulence that felled previous regimes. Interestingly, this is the period during which concerted efforts were made towards realising the comprehensive governance reforms inspired by SADC and the AU, with technical and financial support from the European Union (EU), the Commonwealth Secretariat, UNDP, the UN Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights, and UN Women, among others. It was also during this period that a series of transitional justice interventions were embarked upon: SADC mediation; AU support to security-sector reforms; Phumaphi Commission of Inquiry; the national reform agenda steered by NRA/NRTO (National Reforms Transitional Office); the NRA national stakeholder consultative forum on peace, unity and reconciliation; the Lesotho Council of Non-Governmental Organisations (LCN)–Strategic Institute for Research and Dialogue (SIRD) project on popularisation of the AUTJP; AU/Centre for the Study of Violence and Reconciliation (CSVR) capacity-building for the security sector and civil society on transitional justice; and the ongoing International Centre for Transitional Justice (ICTJ) technical assistance to NRTO aimed at convening a national consultative forum on the development of a national transitional justice policy in Lesotho. More than in the previous periods, table 7 below vividly illustrates that it is during the current period that concerted efforts towards institutionalising transitional justice were made primarily through mediation, commissions of inquiry, national dialogue, governance reforms, constitutional review, popularisation of AUTJP, preliminary evidence-based research on transitional justice by LCN and SIRD and civil society advocacy for the development of a national transitional justice policy.

Table 7: Violence trends, 2012–2025

| Year | Events | Violence and Human Rights Violations | Transitional Justice Response |

| 2012 | General election | Political tension | Power sharing through coalition governance |

| 2014 | Instability within LDF; instability within the Lesotho Mounted Police Service (LMPS); tension between LDF and LMPS; attempted coup; three security chiefs sent on sabbatical out of the country | Political crisis | SADC intervention (diplomatic/military) |

| 2015 | Instability within LDF persists; abduction of some soldiers; others flee the country into exile in South Africa; assassination of Lt. Gen. Maaparankoe Mahao by LDF soldiers; collapse of coalition government leading to a snap election; change of a coalition government | Political crisis | The Phumaphi Commission of Inquiry established by SADC |

| 2017 | Government instability and collapse; snap election; change of coalition government; assassination of Lt. Gen. Khoantle Motšomotšo by LDF soldiers | Political crisis | SADC intensifies its diplomatic and military intervention |

| 2017 | SADC-inspired governance reforms begin; national dialogue is held, national dialogue plenary I (2018) and national dialogue plenary II (2019); NRA is established | Political crisis | Governance reforms |

| 2020 | Coalition government is under strain; tension mounts due to the 2017 assassination of prime minister’s (PM’s) wife (Lipolelo Thamae); PM resigns and is replaced by a new PM | Political tension | Governance reforms |

| 2021 | NRA consultative multi-stakeholder dialogue on peace, unity and reconciliation | Relative political stability | Calls for the institutionalisation of national infrastructures for peace, including a transitional justice policy, intensify |

| 2022 | General election is held; newly established Revolution for Prosperity (RFP) wins the polls six months into its existence; a new coalition government created | Relative political stability | Governance reforms |

| 2024 | LCN and SIRD begin an ATJLF-administered transitional justice project with funding from the AU and the EU | Relative political stability | AUTJP is popularised |

| 2024 | CSVR and AU organise workshops on transitional justice for the security agencies (LDF, LMPS, National Security Service and Lesotho Correctional Service) in Maseru, Lesotho | Relative political stability | AUTJP is popularised |

| 2024 | Three-pronged constitutional amendments proposed: 10th Constitutional Amendment; 11th Constitutional Amendment; and 12th Constitutional Amendment | Relative political stability | The 10th Constitutional Amendment passed by the legislature, and the proposal for the establishment of the National Human Rights Commission is part of this amendment |

| 2025 | ICTJ provides technical assistance to the NRTO to organise a national consultative forum in an effort to develop a national transitional justice policy as part of the ongoing comprehensive governance reforms in Lesotho | Relative political stability | Preparations for the national multi-stakeholder consultative forum in progress as a key step towards the development of a national transitional justice |

Source: Authors’ compilation from Likoti (2007); Deleglise (2018); Kali (2022); Pherudi (2003, 2023), Aerni-Flessner et al. (2025)

6. Relevance of transitional justice and applicability of AUTJP

Transitional justice refers to mechanisms and approaches adopted to redress past atrocities, crimes and human rights violations in the aftermath of war, violent conflict and autocratic rule. It describes “an ever-expanding range of mechanisms and institutions including tribunals, truth commissions, memorial projects, reparations and the like to redress past wrongs, vindicate the dignity of victims and provide justice in times of transition” (Buckley-Zistel et al., 2014:1).

Transitional justice initiatives encompass various components, including criminal prosecution and trials, truth commissions, reparations, gender justice, institutional reforms, psychosocial support, and memorialisation (United States Institute of Peace, 2008). These are adapted (and could even be expanded) to the specific context of each country with a view to achieve the following key goals: “Establish truth about what happened and why, acknowledge victims’ suffering, hold perpetrators accountable, compensate for past wrongs, prevent future abuses and promote social healing” (United States Institute of Peace, 2008:1). Transitional justice builds firm foundations for transitioning countries for transformative justice encompassing retributive justice (punishment), restorative justice (rehabilitation), reparative justice (communal harmony) as well as distributive justice (equality and equity).

Despite the prevalent violence and its deleterious effects, little to no efforts have been invested in institutionalising transitional justice as a response mechanism in Lesotho. Half-hearted responses have included instituting commissions of inquiry, convening national dialogue fora, inquests, indemnity/amnesty and prosecution. These efforts have proved far less effective. What is required, therefore, are concerted and deliberate efforts aimed at institutionalising national infrastructures for peace (I4Ps), encompassing robust transitional justice mechanisms. I4Ps broadly refer to a dynamic network of interdependent structures, mechanisms, resources, values, and skills that, through dialogue and consultation, contribute to the prevention, management, and resolution of violent conflicts and provide a foundation for sustainable peace, security, and stability in a society. These institutions, platforms and networks conventionally take the form of National Peace Committees (NPCs) operating at local, district, provincial and national levels involving parties in conflict, governments and CSOs. NPCs mediate local conflicts and facilitate constructive dialogue among disputants, often using insider mediators and mainly relying on customary/traditional alternative dispute-resolution mechanisms. The ongoing national reform process presents a golden opportunity for establishing effective transitional justice mechanisms in Lesotho. What then is the relevance of the AUTJP for Lesotho?

The AUTJP provides a comprehensive normative framework comprising eleven core pillars and several cross-cutting issues intended to guide AU member states in addressing past human rights violations and establishing sustainable peace (AU, 2019). This section applies each of these pillars to the Lesotho context, drawing on national dialogues, policy efforts, scholarly literature and key theoretical models of justice to assess how Lesotho can adopt and implement a contextually grounded transitional justice framework aligned with the AUTJP.

Given that Lesotho is one of the 55 member states of the AU, its transitional justice process has to be aligned with the 11 core pillars of the AUTJP, albeit adapted to the country’s peculiar context. The 11 AUTJP pillars are: (i) peace processes; (ii) transitional justice commissions; (iii) African traditional justice mechanisms; (iv) reconciliation and social cohesion; (v) reparations, (vi) redistributive (socio-economic) justice; (vii) memorialisation; (viii) diversity management; (ix) justice and accountability; (x) political and institutional reforms; and (xi) human and peoples’ rights. The Lesotho transitional justice process should also mainstream the cross-cutting issues, notably (a) victims and survivors; (b) women and girls; (c) children and youth; (d) persons with disabilities; and (e) older persons (AU, 2019).

The AUTJP emphasises the importance of integrating transitional justice into broader peacebuilding efforts. Although Lesotho has not experienced civil war, it faces entrenched political violence and instability. Ranked 125 out of 163 in the 2024 Global Peace Index (Institute for Economics and Peace, 2024), this low rating reflects persistent inequalities, elite contestation and institutional fragility.

The establishment of the NRA in 2019 was an attempt to initiate reform and foster reconciliation. A key milestone was the July 2021 national forum, which advanced victim-centred peacebuilding recommendations, including decentralised peace structures, a comprehensive transitional justice commission and reparations. These efforts align with restorative justice models, particularly Braithwaite’s (2002) emphasis on inclusive dialogue, truth-telling and reconciliation.

Yet the government’s 2021 National Peace and Unity Bill, criticised for excluding victims and lacking transparency, contradicted the participatory ethos of procedural justice and undermined the moral imperative of accountability central to retributive justice (Kant, 1996).

The establishment of transitional justice commissions reflects the operationalisation of restorative justice mechanisms through institutional structures. Lesotho’s various national dialogues – from the 1995 LCN forum to the 2019 Plenary II Report – highlighted the need for a National Reconciliation Commission. These commissions would ideally balance retributive demands (accountability) with restorative goals (healing and reintegration), while providing a legal and institutional base for truth-seeking. However, political inertia has delayed implementation, raising concerns about the country’s commitment to dismantling the culture of impunity.

Traditional justice mechanisms in Lesotho, led by chiefs, elders and healers, embody restorative justice in practice. These systems, rooted in communal ethics and consensus-building, are indispensable for social cohesion in rural areas (African Development Bank, 2024). Yet their exclusion of women and youth undermines procedural fairness, while their subordination to statutory law limits their potential to contribute to a nationally integrated transitional justice framework.

Lesotho’s history of repression has weakened the cultural and institutional bases for reconciliation and social cohesion. Political trauma and fragmentation – particularly under democratic governance – necessitate deliberate efforts at national healing. As Braithwaite (2002) and the AUTJP suggest, reconciliation must be people-centred, inclusive and grounded in truth, forgiveness and reintegration.

Imperatives for reparations in Lesotho are inextricably linked to both restorative and redistributive justice. The 2021 NRA dialogue proposed broad compensation mechanisms, including land return, employment and psychosocial support. These measures also align with Sen’s (2009) vision of justice, which emphasises enhancing substantive freedoms and addressing real-life deprivations. Yet the lack of a victim registry and institutionalised mechanism for delivery remains a critical gap.

The pursuit of redistributive (socio-economic) justice will go a long way to redress the adverse effects of contemporary development challenges confronting Lesotho. The country’s pervasive inequality reflects more profound structural injustices. Poverty, unemployment and marginalisation fuel instability. Following Rawls (1971) and Sen (2009), redistributive justice requires that transitional justice address unequal access to social goods and economic opportunities. Inclusive development, food security and equitable access to employment – especially for youth and women – are prerequisites for lasting peace.

Memorialisation strategies serve as symbolic restorative justice interventions. They validate the suffering of victims, promote historical truth, and deter recurrence. Lesotho’s weak memorial tradition – exemplified by the absence of state-led initiatives – limits national dialogue on past violations. Institutionalising commemorative practices (e.g., monuments, educational reforms) would bridge historical memory and civic education.

Though often perceived as homogeneous, Lesotho exhibits significant intra-ethnic, clan and cultural diversity. Mismanagement of diversity exacerbates socio-cultural and politico-economic cleavages. Drawing on procedural justice, the AUTJP emphasises inclusive policy frameworks that foster pluralism, tolerance, and equitable representation (UNDP, 2004; Deng, 2008).

Justice and accountability are key to reconciliation, truth-seeking, national healing and social cohesion, all of which are necessary ingredients for sustainable peace. Accountability is central to retributive justice, which demands punishment proportionate to wrongdoing (Kant, 1996). Lesotho’s politicised judiciary and partisan security institutions have eroded public trust and enabled impunity. Strengthening judicial independence, civilian oversight, and due process is essential for delivering justice and preventing recurrence.

Political and institutional reform constitutes both a goal and a vehicle for transitional justice. Although the NRA laid a solid foundation, its limited timeframe and lack of political backing hindered progress. Sustainable transitional justice depends on a permanent reform body that institutionalises both procedural justice (inclusive decision-making) and distributive justice (equitable power sharing and representation).

Lesotho’s legacy of politically motivated violence, police abuses and social exclusion reflects a fundamental failure to uphold human and peoples’ rights. The AUTJP, in line with the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights, requires governments to inculcate a rights-respecting culture. Human rights violations are both the cause and effect of political violence.

In its journey to institutionalise transitional justice for sustainable peace, Lesotho must ensure that key cross-cutting issues are addressed. The embedded culture of SGBV against women and girls has to be eradicated. Victims and survivors of human rights violations have to participate meaningfully in transitional justice mechanisms. The interests and fears of other marginalised social groups, such as children, youth, persons with disabilities, older persons and minority groups, have to be factored into the design and development of transitional justice policy and institutional frameworks. These groups often face multiple, intersecting disadvantages.

7. Synthesis and implications of the political violence trends on transitional justice

This section synthesises two evidence streams: (i) a qualitative, historical analysis across six phases (1966–2025); and (ii) a cross-sectional survey of influential stakeholders measuring basic awareness of the AUTJP. The documentary analysis surfaces recurring patterns of violations and state responses; the survey offers a contemporary snapshot of stakeholder familiarity with the AUTJP.

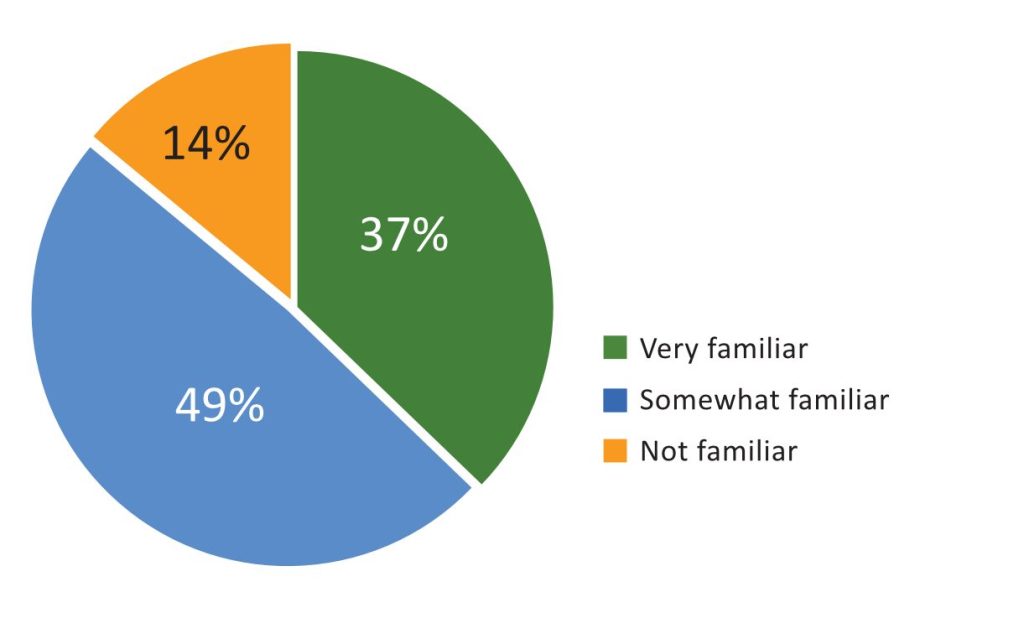

A significant number of respondents were either very familiar (37.2%) or somewhat familiar (48.8%) with the AUTJP (see Figure 2). This illustrates that the recent awareness-raising efforts, particularly those undertaken under the transitional justice project jointly led by the LCN and the SIRD, have begun to yield results. These efforts, funded by the Africa Transitional Legacy Fund, popularised the AUTJP across the 10 districts of Lesotho from July 2024 to September 2025 and advocated for the adoption of a national transitional justice policy. The 14% of participants who were not familiar at all with the AUTJP still indicate the need for broader public sensitisation and capacity-building efforts if a national transitional justice policy is to be inclusive and well-understood.

Figure 2: Respondents’ general awareness of transitional justice and the AUTJP

Source: Authors’ compilation

Finally, nearly 68% of participants reported being aware of the broader concept of transitional justice. This suggests that while many stakeholders are familiar with transitional justice as a concept, fewer have been explicitly exposed to the AUTJP framework, highlighting a key entry point for advocacy and education as part of the preparatory stages leading up to the development and adoption of a national transitional justice policy. Linkages between the findings and the AUTJP reveal five patterns: recurrent abuses and weak accountability, low participation and political resistance, gender injustice, resource constraints, and low levels of awareness of the AUTJP.

Across all six phases, coercive state power and elite contestation produced recurrent abuses – summary killings, politically motivated assassinations, forced exiles and security-sector impunity, only episodically interrupted by inquiries or prosecutions. Where responses occurred (for instance, commissions, isolated trials, limited compensation), they were ad hoc, seldom rising to systematic truth-telling, victim-centred reparation, or durable guarantees of non-recurrence.

This pattern aligns with comparative insights that fragmented measures rarely dislodge entrenched impunity (Teitel, 2000; Hayner, 2011) and echoes local diagnoses of a persistent ‘culture of violence’ (Thabane, 2017; Matlosa, 2020). The implication for the AUTJP is clear: accountability and truth mechanisms must be legally grounded, sequenced and shielded from partisan interference if they are to reset norms.

Periodised evidence shows that participation has repeatedly narrowed under authoritarian rule, post-election crises, and security-sector politicisation, with resistance being channelled into protests, mutinies, or spoiler behaviour. The literature warns that exclusion and ‘winner-takes-all’ incentives fuel cyclical instability; Lesotho’s electoral redesign to MMP eased but did not eliminate these dynamics. Under the AUTJP, the diversity management and political and institutional reform pillars require opening channels for meaningful participation (including youth, women, and minorities) within parties, parliament, local government, and oversight bodies – transforming resistance into an institutional voice.

The record indicates that SGBV and gendered harms are interwoven with political violence and insecurity. Yet reparative and psychosocial responses remain sporadic. Comparative transitional justice literature underscores that gender-responsive design (safe reporting, survivor services, and memorialisation recognising gendered harms) improves legitimacy and healing (Braithwaite, 2002; UNDP, 2004). The AUTJP’s cross-cutting lens requires survivor-centred procedures, quotas in body composition and targeted reparations for women and girls alongside community-level reconciliation.

Even where reform intent exists (in the form of commissions, dialogues, or proposed legislation), constrained fiscal space, fragmented mandates, and thin psychosocial infrastructure limit follow-through. The AUTJP foregrounds redistributive justice precisely because resource inequities sustain grievances and hobble institutions (Rawls, 1971; Sen, 2009). Practically, this means ring-fenced budgets for transitional justice bodies, victim registries, case management systems, and community-level healing services; without these, truth and accountability remain mere promises on paper.

High overall awareness of transitional justice among elites suggests a window of opportunity for policy convergence around an AUTJP-aligned framework. Still, the unfamiliar minority signals the need for sustained outreach beyond capitals – to districts, traditional authorities, youth, and women’s groups. Alignment with the pillars of the peace processes and the transitional justice commission would entail a sequenced roadmap that couples truth-seeking with survivor services, integrates traditional justice consistent with rights, and institutionalises memorialisation to anchor memory and prevent recurrence.

Taken together, the six-phase record and contemporary awareness picture point to a transitional justice pathway that is nationally owned, gender-responsive, resource-realistic and institutionally embedded – precisely the direction envisaged by the AUTJP. The findings do not merely describe history; they identify leverage points where reforms, if properly designed and funded, can bend the cycle away from impunity towards accountable peace.

Overall, the study’s key findings coalesce into five thematic areas across Lesotho’s six phases: recurrent (at times sporadic) abuses and weak accountability; narrow political participation and resistance; persistent gender-justice gaps; resource and capacity constraints; and uneven AUTJP awareness. These patterns, and the essentially ad hoc responses to them, underscore the need for an integrated AUTJP-aligned approach. Table 8 distils these dynamics and links each theme to the relevant AUTJP pillars, clarifying concrete policy entry points.

Table 8: Findings – AUTJP linkage matrix

| Thematic Finding | What the Evidence Shows | AUTJP Pillars Activated |

| Recurrent abuses and weak accountability | Episodic inquiries/limited prosecutions; impunity cycles | Justice and accountability; truth; memory |

| Participation and political resistance | Narrowed voice; spoiler behaviour; fragile coalitions | Diversity management; human and peoples’ rights; political and institutional reform |

| Gender-justice gaps | SGBV; limited survivor services; minimal gendered reparations | Cross-cutting: women and girls; reparations; reconciliation and social cohesion |

| Resource/capacity constraints | Underfunded bodies; no victim registry; weak psychosocial support | Redistributive justice; political and institutional reform; reconciliation |

| Awareness of AUTJP | High among elites, uneven beyond | Peace processes; transitional justice commissions; traditional justice; memorialisation |

Source: Authors’ compilation

8. Conclusion and recommendations

This paper makes a case for various stakeholders to make deliberate efforts to uproot the culture of violence in Lesotho. It shows that violent conflicts and instability in the country undermine socio-economic development, sustainable peace and democratic governance. Violent conflicts also lead to human and people’s rights violations, with the hardest-hit social groups being women and girls, children and youth, minority groups, persons with disabilities, as well as older persons. Lesotho, therefore, needs to inculcate a culture of peace, justice and reconciliation informed by the 11 indicative elements and three sets of cross-cutting issues that form the bedrock of the AUTJP.

For transitional justice to bear palatable fruit, the culture of violence, impunity and fear in the country has to be rooted out and eradicated altogether. The relevance of transitional justice and applicability of the AUTJP in Lesotho must draw on the theoretical models of retributive, restorative and redistributive justice, each addressing different dimensions of historical harm. Retributive justice demands accountability; restorative justice fosters reconciliation; and redistributive justice confronts systemic inequality.

There is a need for a broad-based discourse and debate on transitional justice as a core component of peacebuilding. This requires research, dialogue and media outreach to popularise the AUTJP. This process has begun in earnest with an ongoing project jointly implemented by the LCN and the SIRD.

For Lesotho to institutionalise transitional justice aligned to the AUTJP, six essential steps are proposed. First, predicated on the research and dialogue, Lesotho should design and develop its own national transitional justice policy framed in conformity with the AUTJP. Both state and non-state actors must play their rightful roles in this process, especially victims of human rights violations. Second, the policy should be anchored on a legal framework in the form of an enabling legislation promulgated by parliament. Third, the legislation should provide for the institutional architecture of the transitional justice process in Lesotho, and key among these are the proposed national peace and reconciliation commission and the human rights commission.

Fourth, the policy and legislative framework for transitional justice must ensure that both modern and traditional transitional justice mechanisms are recognised and insulated from undue political influence. However, deliberate efforts must be made to ensure that traditional transitional justice systems do not reinforce existing power imbalances that marginalise women and youth, in particular. Fifth, both state and non-state actors must aggressively mobilise internal and external resources for the effective implementation, monitoring, evaluation and review of transitional justice processes in Lesotho. Sixth, while all the cross-cutting issues are mainstreamed and integrated into all transitional justice processes, particular attention must be paid to ensuring that victims and survivors are organised and empowered so that they are able to more meaningfully participate and influence decisions. The lack of a victims’ network championing the collective interests of victims and survivors still remains a major hindrance. Ultimately, Lesotho’s successful domestication of the AUTJP requires the integration of moral imperatives, legal safeguards and participatory approaches to build a just, inclusive and peaceful future.

Acknowledgements

We sincerely extend our appreciation to the three research assistants at the SIRD – Mrs Sophy Sutha, Ms Motena Khuto and Ms Matŝele Sesoane – for their dedicated support during the project public consultations, dialogue processes and for their invaluable assistance during the process of data collection, collation and transcription of the rich conversations during in-district public consultations. We also extent our appreciation to the reviewers who provided comments that helped improve the quality of this article.

Reference list:

Aerni-Flessner, J., Fogelman, C. and Mokoena-Mokhali, N. (2025) Historical dictionary of Lesotho. 3rd ed. Boulder, Rowman & Littlefield.

African Development Bank. (2024) Country focus report: driving Lesotho’s transformation. African Development Bank Group, Abidjan, Côte d’Ivoire.

African National Congress (ANC). (2023) ANC statement on the Maseru massacre in 1982 [Internet]. Available from: <https://www.anc1912.org.za/anc-statement-on-the-maseru-massacre-in-1982/>

African Union. (2019) African Union Transitional Justice Policy. African Union Commission [Internet]. Available from: <https://au.int/sites/default/files/documents/36541-doc-au_tj_policy_eng_web.pdf>

Amnesty International. (1992) Lesotho: torture, political killings and abuses against trade unionists. AI Index: AFR 33/01/92. Amnesty International [Internet]. Available from: <https://www.amnesty.org/en/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/afr330011992en.pdf>

Bardill, J. and Cobbe, J. (1985) Dilemmas of dependence in Southern Africa. London, Westview Press.

Braithwaite, J. (2002) Restorative justice and responsive regulation. Oxford, Oxford University Press.

Buckley-Zistel, S., Beck, T., Braun, C. and Meith, F. (2014) Transitional justice theories: an overview. In: Buckley-Zistel, S., Beck, T., Braun, C. and Meith, F. eds. Transitional justice theories. London, Routledge. pp. 1–15.

Deleglise, D. (2018) The rise and fall of Lesotho’s coalition governments. In: Complexities of coalition politics in Southern Africa. ACCORD Monograph Series No. 1/2018 [Internet]. Available from: <https://www.accord.org.za/wp-content/uploads/2024/06/Monograph-2018-The-rise-and-fall-of-Lesothos-coalition-governments.pdf> (Accessed on 28 May 2025)

Deng, F.M. (2008) Identity, diversity, and constitutionalism in Africa. Washington, DC, United States Institute of Peace Press.

Fox, R. and Southall, R. (2003) Adapting to electoral system change: voters in Lesotho, 2002. Journal of African Elections, 2 (2), pp. 86–96.

Government of Lesotho. (2017) The Lesotho we want: dialogue and reform for national transformation. Maseru, Lesotho.

Government of Lesotho. (2019a) Multi-stakeholder national dialogue, Plenary II report, 25–27 November, Manthabiseng Convention Centre.

Government of Lesotho. (2019b) National Reforms Authority Act. Vol. 64, No. 62; 8 November. Maseru, Government Printer.

Hayner, P.B. (2011) Unspeakable truths: transitional justice and the challenge of truth commissions. 2nd ed. London, Routledge.

Institute for Economics and Peace (IEP). (2024) Global peace index 2024: measuring peace in a complex world. Sydney, Institute for Economics and Peace.

Kali, M. (2022) The untold story of civil society organisations’ contribution to peacebuilding in Lesotho. International Politics, 59, pp. 1082–1100.

Kant, I. (1996) The metaphysics of morals. Gregor, M. ed. and trans. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press.

Kapa, M. (2017) Roles of civil society in conflict situations in Sub-Saharan Africa: the case of Lesotho. In: Berhanu, K. and Chimanikire, D. eds. The roles of civil society in conflict management and peacebuilding in Eastern and Southern Africa. Addis Ababa, Organisation for Social Science Research in Eastern and Southern Africa. pp. 259–288.

Khaketla, M. (1972) Lesotho 1970: an African coup under the microscope. Berkeley, California University Press.

Likoti, F. (2007) The 1998 military intervention in Lesotho: SADC peace mission or resource war? International Peacekeeping, 14 (2), pp. 251–263.

Machobane, L. (2001) The king’s knights: military governance in the Kingdom of Lesotho, 1986–1993. Roma, National University of Lesotho.

Matlosa, K. (1999) Conflict and conflict management: Lesotho’s political crisis after the 1998 election. Lesotho Social Science Review, 5 (1), pp. 163–196.

Matlosa, K. (2020) Pondering the culture of violence in Lesotho: a case for demilitarisation. Journal of Contemporary African Studies, 38 (3), pp. 381–398.

Monyake, M. (2020) Assurance dilemmas of the endangered institutional reforms process in Lesotho. Canadian Journal of African Studies / Revue Canadienne des Études Africaines, 56 (1), pp. 181–198.

Monyane, C. (2009) The Kingdom of Lesotho: an assessment of problems in democratic consolidation. Doctoral dissertation, Stellenbosch University [Internet]. Available from: <https://scispace.com/pdf/the-kingdom-of-lesotho-an-assessment-of-problems-in-40gor7j6i8.pdf>

National Reforms Authority. (2021) The path towards sustainable peace, national unity and reconciliation: the Lesotho we want. Report of the National Stakeholder Consultative Forum, 21–23 July, Manthabiseng Convention Centre.

Pherudi, M. (2003) Operation Boleas under microscope, 1998–1999. Southern African Journal of History, 28 (1), pp. 123–137.

Pherudi, M. (2023) Lesotho on SADC agenda: challenges of instability and prospects for peace. Pretoria, UNISA Press.

Rawls, J. (1971) A theory of justice. Cambridge, MA, Harvard University Press.

Sen, A. (2009) The idea of justice. Cambridge, MA, Harvard University Press.

South African History Online (SAHO). (2011) South Africa closes its borders with Lesotho [Internet]. Available from: <https://sahistory.org.za/dated-event/south-africa-closes-its-borders-lesotho>

Teitel, R.G. (2000) Transitional justice. Oxford, Oxford University Press.

Thabane, M. ed. (2017) Towards an anatomy of persistent instability in Lesotho, 1966–2016. Roma, National University of Lesotho.

United Nations Development Programme (UNDP). (2004) Human development report 2004: cultural liberty in today’s diverse world. New York, UNDP.

United States Department of State. (1999) Lesotho: country reports on human rights practices for 1998 (rev. May 25, 1999). Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor [Internet]. Available from: <https://1997-2001.state.gov/global/human_rights/1998_hrp_report/lesotho.html>

United States Institute of Peace. (2008) Transitional justice: information handbook. Washington, DC, United States Institute of Peace.