Mr Israel Nyaburi Nyadera is a graduate of the University of Nairobi Department of Political Science and History. He holds a Masters in International Relations from Middle East Technical University and a Masters in Political Science from Ankara Yildirim Beyazit University. He is currently a Ph.D. researcher in the same department and has been a visiting researcher to the University of Milan.

Abstract

With the South Sudanese conflict in its fifth year in 2018, this paper seeks to not only examine the status of the civil war that has engulfed the youngest nation on earth but to also discuss the evolving narratives of its causes and provide policy recommendation to actors involved in the peace process. Having examined the continuously failing peace treaties between the warring parties, it is evident that the agreements have failed to unearth and provide solutions to the crisis and a new approach to examining the causes and solutions to the problem is therefore necessary. This paper argues that ethnic animosities and rivalry are a key underlying cause that has transformed political rivalry into a deadly ethnic dispute through vicious mobilisation and rhetoric. Therefore, it recommends a comprehensive peace approach that will address the political aspects of the conflict and propose restructuring South Sudan’s administrative, economic and social spheres in order to curb further manipulation of the ethnic differences.

Introduction

South Sudan became the youngest nation in the world after splitting from the larger Sudan to become the Republic of South Sudan in 2011. However, their independence, like that of other countries in the world, came with a huge human cost following decades of intense conflict between the Arab North and the non-Arab South. The intensity of the conflict was so destructive that it caught the attention of the international community, who embarked on a series of mediation and negotiation processes between the North and the South. Following several protocols and agreements signed by representatives of the North and the South between 2002 and 2004 (Jok 2015:1–5), these processes culminated in the signing of the Comprehensive Peace Agreement (CPA) on 9 January 2005. However, as the separation process was taking place, several key issues that were responsible for mistrust among groups in the non-Arab South were not addressed.

The main focus was on the conflict between the North and the South and not the ‘frozen’ and ‘cold’ relations among the different ethnicities in the South. The referendum was overwhelmingly in favour of separation, with 99% of the votes cast approving the decision. For the North, however, this marked a major downgrade of their country’s land mass as one-third of the land and about three-quarters of its oil reserves went to the new Republic of South Sudan (Ottaway and El-Sadany 2012:3).

The objective of this paper is to revisit the status of and events surrounding the South Sudan conflict from a historical and contemporary perspective and assess the consequences after five years of continued fighting. It also seeks to emphasise the role of ethnic animosity as the main underlying cause of the transformation from political rivalry to violent conflict and the way in which other causes are attached to the ethnicity factor. Recommendations will then be provided to address the political, economic and ethnic differences in the country. The paper recommends an exit strategy that will ensure the gaps that allowed previous peace agreements to collapse are sealed by involving local, regional and international actors. It proposes a transitional authority that will help deconstruct the myth that ethnicity is the basis of survival and instead suggests the establishment of a government that will regain public trust and confidence through better management and distribution of resources, restructuring and retraining the country’s security forces – ensuring territorial integrity and a state monopoly on the use of force. All of these may be achieved through the adoption of an elaborate constitutional reform.

The data used in this paper was obtained through rigorous thematic analysis of existing literature on the South Sudan conflict. The author used the data to identify the present status of the conflict, and examine the narratives on the causes of the conflict and on the various peace agreements. This way, it becomes apparent that ethnicity was not given the attention it deserves, as the focus was on ending the violence through political power sharing rather than addressing the ethnic and economic grievances. Based on the findings, an elaborate peace approach has been recommended: one that will dilute the short and long term impacts of ethnicity and allow the young nation to benefit from the fruits of its independence.

Status of the conflict

The government of South Sudan is experiencing a struggle over legitimacy and monopoly on the use of force. Weber’s definition of the state is largely based on the state’s ability to have a monopoly of force. This argument is supported by several realist theorists like Waltz (1998:28–34), some of them pointing out that although such control will enable the state to have authority over other actors, this authority should not be abused (Thomson and Krasner 1989; Krasner 1999). The moment a state loses control of the monopoly over the use of force, be it through a union, revolution, collapse or conquest, then the state is dead (Adams 2000:2–5). In the case of South Sudan, the situation has remained alarming as legitimacy and monopoly over the use of force is not solely in the hands of the current government since the opposition has significant support, legitimacy and a strong army of fighters which has taken control of several parts of the country.

Weeks into the fighting that began in 2013, the United Nations (UN) estimated that thousands had been killed, and around 120 000 others internally displaced – of whom around 63 000 were seeking shelter at the UN Peacekeeping Base (UNOCHA 2013). The UN Security Council was called into action rapidly with the unanimous adoption of Resolution 2132 that required an increase of the number of troops serving under the United Nations Mission in South Sudan (UNMISS) to 12 500 soldiers and immediate cessation of hostilities (UNSC 2013). To show the seriousness of the South Sudanese case, Secretary-General Ban Ki-Moon authorised the transfer of troops from other conflict regions such as the African Union-United Nations Hybrid Operation in Darfur (UNAMID), the United Nations Operation in Côte d’Ivoire (UNOCI), the United Nations Organisation Stabilisation Mission in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (MONUSCO) and the United Nations Mission in Liberia (UNMIL). Such a drastic response can be explained by the fact that although it is not very clear how many people had been killed in the first three months, aid agencies put the figure at over 50 000 people, which is higher than those who had been killed in Syria at the time – and that while the population of South Sudan is only about half of that of Syria (Martell 2016.).

The conflict continued with heavy casualties witnessed until 2015, when a temporary peace treaty was signed (Blackings 2016:7). Cessation of hostilities did not last long as both sides accused each other of violating the terms of the peace treaty. Episodic violence kept erupting as the country remained unstable. Even the Southern parts that were relatively peaceful and known for their high crop yields came under attack. This affected food production in the country and diminished supply quantities. The government lost monopoly over coercive power and was unable to administer justice, provide basic services to the citizens and guarantee their security. Domestic sovereignty and more particularly the legitimacy of the political elites were highly disputed as the country was staring into a possible genocide (African Union 2014:106, 276).

In 2017, four years into the war, the number of displaced persons had increased to over 2.3 million people, and renewed fighting was taking place in the Equatorials, Western Bahr al Ghazal and the Greater Upper Nile, causing the death of thousands more (UNHCR 2018). The government was accused of illegal detentions, restriction of media freedom and suppression of critics. The number of people seeking shelter at UN peacekeepers’ bases had also increased to 230 000 from 63 000. The situation was made even worse with the outbreak of a severe famine, especially in the former Unity state, which lasted for more than six months. The unchecked violence has seen war crimes and crimes against humanity committed, according to the African Union Commission of Inquiry. In 2018, reports by the Mercy Corps indicate that 1 out of 3 people in South Sudan is a refugee, 1.9 million people are internally displaced while more than 2.1 million have fled out of the country. This shows an increase in the number of internally and externally displaced persons from 2 million to 4 million (Mercy Corps 2018). Already, approximately $20 billion has been spent by the UN on its peacekeeping missions in South Sudan since 2014 – with little results in terms of achieving sustainable peace (Rolandsen 2015:355–356).

Targeted attacks on civilians, gender-based violence including rape, burning of homes and livestock, murder and kidnapping continue to be widespread. Aid convoys continue to be attacked and relief food looted by different warring groups. According to the United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund (UNICEF), almost 50% of all children eligible to be enrolled are out of school. The violence continues to affect not just school-going children, but also farmers and other workers who have abandoned their duties to find other means of surviving. The situation in South Sudan is among the worst in the world. Understandably so because the region became independent after three decades of fierce fighting with the North. Before the dust of the independence celebrations even settled, the civil war erupted, and as a result there was no adequate time to establish institutions and response mechanisms that could have at least reduced the effects of the war. This has seen South Sudan ranked the highest on the world index of fragile states that can collapse anytime. Inadequate funding has been a big challenge, too, in facing the conflict. For example, the budget needed to respond to the crisis in 2017 was $1.64 billion, which was expected to help 7.6 million beneficiaries. However, only 73% of the total budget was financed. In 2018 the targeted budget by the UN is $1.8 billion to help the internally displaced and $1.7 billion to assist those who have fled out of the country (Reuters 2017b). Given the failure to meet the full budget in the previous years, aid agencies may need to look to the private sector among other options, for sufficient funding. Lack of funds is further worsened by the excess spending and extravagant lifestyle of the political class (Waal 2014:362–364).

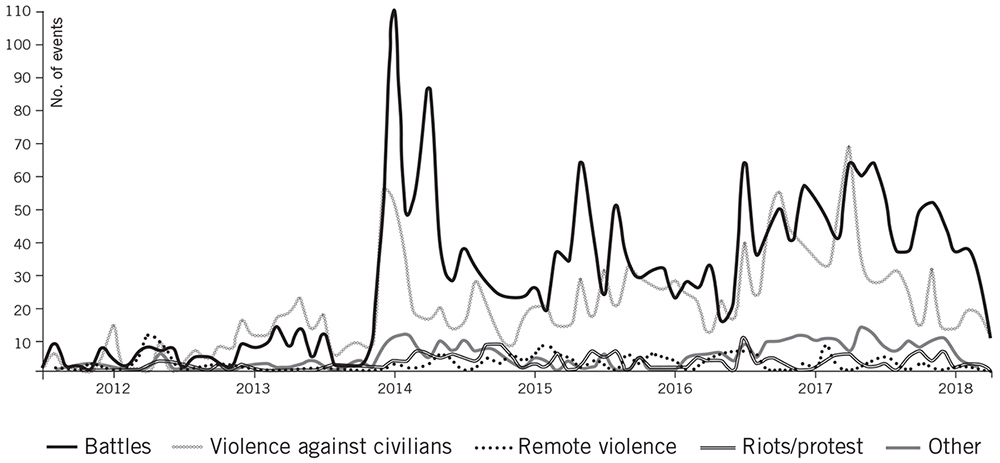

Graph showing the number of conflict incidences from 2011 to 2018

The International Monetary Fund (IMF) is warning that the prolonged war threatens a complete collapse of the South Sudanese economy if the large economic imbalances and exhausted economic buffers are not addressed (Sudan Tribune 2016). The economic situation in the country suffered a serious blow from the global oil price decline since 98% of the government revenue comes from oil exports. The South Sudanese Pound also lost around 90% of its value following the 2015 liberalisation of exchange rates that saw the country lose ground against other global currencies (Sudan Tribune 2017). In 2016 inflation surpassed the 550% increase rate leaving the government with over $1.1 billion deficit in the 2016–2017 financial year (IMF 2017). Wages were significantly reduced while the prices of even the most basic products skyrocketed – inflicting more suffering on the people. For example, the price of sorghum had increased by 400%. (FEWSN 2016).

Recent developments

The civil war has remained persistent since the collapse of the 2015 peace agreement that was mediated by the Intergovernmental Authority on Development (IGAD) (Knopf 2016:12). During this time, several efforts have been made to attract the leaders back to the negotiating table, but all of them were in vain. In early May 2018, peace talks resumed in Addis Ababa, but by the end of the month the meetings ended without any formal agreements. Both parties rejected the proposal presented by IGAD on the sharing of government positions, the governance system of the country, and, most importantly, the security arrangements.

On 25 June 2018, following intense pressure, President Salva Kiir and Riek Machar met in Khartoum for the first time in two years (The Star 2018). The meeting was concluded with the signing of a new peace agreement that called for a countrywide cease-fire as well as the sharing of government positions. The cease-fire was just hours later violated in the Northern part of the country with both parties accusing the other of the violation. The almost immediate violation of the agreement leaves analysts sceptical on whether this particular one will hold longer, given that previous agreements have not been honoured. Factors that threaten the new agreement are the creation of positions for four vice-presidents, and efforts to extend the presidential term again by three years – given that elections were supposed to be conducted in 2015 but were not. The resumption of oil exploration is another contentious point of the agreement about which the opposition are still expressing concerns. Apart from the cease-fire, the agreement package provides for a 120-day pre-transition period and a 36-month transition period that will be followed by a general election and the withdrawal of troops from urban areas, villages, schools, camps, and churches. Noteworthy, other groups have also found their way into the negotiations and will also have a share of the executive and parliamentary slots shared by the two main protagonists. Their presence when an agreement was signed in Kampala, Uganda on the 8th of July 2018 has earned them a slot among the proposed four positions of the vice-presidency. While this peace agreement is a welcome move, it does not adequately deal with the reasons which had caused the collapse of previous agreements. We will later examine why these forms of power-sharing deals may not be sufficient to end the ongoing civil war.

Narratives on the causes of the conflict

The devastating consequences of the South Sudan conflict have prompted several scholars to come up with narratives as to the circumstances that have led to the conflict (Ballentine and Nitzschke 2005, Doyle and Sambanis 2000, O’Brien 2009). Some of these narratives touch on natural resources (especially oil), others on the access and availability of arms, or the role of Sudan in the conflict. While these narratives may have merit, they fail to examine some of the most critical underlying causes of the conflict. This is what necessitates the rethinking of the ways in which the conflict has been presented academically. Below are some of the arguments and their gaps.

The narrative of oil fuelling the civil war in South Sudan has been highly favoured by various scholars who argue that the warring parties are keen on controlling oil and other natural resources (Ballentine and Nitzschke 2005:6–7; Sachs and Warner 2001:827–838). Fearon and Laitin (2003:75–90) and De Soysa (2002:409) adopted different data sets, but also concluded that there is a causal relationship between oil resources and civil wars. Indeed, in the case of South Sudan, oil is the most important source of government revenue, and oil-producing states such as Unity, Jonglei, and Upper Nile have seen the worst of the civil war with some of the most intense combat operations reportedly happening in these areas. An investigative initiative conducted by Sentry, a US-based think-tank, gave a report alleging that oil revenues are used to finance and sustain the ongoing civil war and to enrich a small group of people in South Sudan (Bariyo 2014). This report was dismissed by the government spokesperson, Ateny Wek Ateny Sefa-Nyarko, who during an interview with Reuters insisted that oil revenues are being used to pay civil servants, stating: ‘The oil money did not even buy a knife. It is being used for paying the salaries of the civil servants’ (Reuters 2014). There are also scholars, such as Sefa-Nyarko (2016:194), Johnson (2014:167) and others, who contend that the civil war of South Sudan cannot be explained using the perspective that the natural resource curse is its primary cause.

There has already been much argument on the question of why and how income from natural resources, and not income from other sources – such as agriculture, would cause conflict. Often, however, the proponents of civil wars being caused by natural resources fall short of providing a convincing argument. The media tend to use expressions such as the war has been ‘fuelled’ by the existence of natural resources but fail to explain how it happened. The literature concerned still needs to address three important aspects, the first of which is the possibility of spurious logic in regard to the place of endogeneity. That is, the potential that the correlation can actually be the opposite in the sense that natural resource dependency can be a product of civil war. Natural resources are in most cases location-specific, so even in times of war they remain constant while mobile sectors such as industries can flee. South Sudan has been at war for more than half a century and it is only the oil sector that has been sustaining not simply the war but the economy. Secondly, the natural resource narrative needs to present, in a clear way, which conflicts are affected by which resources and how such resources affect the duration of a conflict. In this regard the claims of Collier, Hoeffler and Söderbom (2004:263) on the one hand, and of Doyle and Sambanis (2000:798) and Stedman and others (2002:12–18), on the other hand, can be compared. Thirdly, the argument that natural resources provide rebels with an opportunity to extort money from miners (Ross 2002:9–10) needs to explain why stricter mining security measures have not been put in place and why a group of rebels who is able to generate revenue by controlling natural resources would opt to engage in violence – unless there were an already existing problem.

The second narrative concerns the ease of access to arms enjoyed by the warring parties. This narrative has some merit and cannot be dismissed in its entirety. After successfully carrying out an armed resistance against the Arab North, the new nation was so overwhelmed by celebrations of their achievement that they failed to recognise the importance of complete disarmament of the civilians at the very early stages of independence. These arms have no doubt played a crucial role in the continuation and escalation of the civil war, since not only the state security agencies had access to arms, but civilians were able to keep the arms they used to fight for independence and thus challenge the state’s monopoly on the use of force (O’Brien 2009:11). The critical role that access to arms has played in the civil war has been recognised by state and non-state actors who have continued to call on the UN and the Security Council to impose an arms embargo on South Sudan. The impact of such a move on the country has not been discussed in this forum, but it is important to note that the United States in February 2018 recognised the impact access to arms has on the current state of South Sudan, and imposed an arms embargo on South Sudan – a move that prevents American citizens and companies from providing defence services to South Sudan (Reuters 2018). This narrative, however, does not explain what motivates a South Sudanese citizen to point a gun and kill a fellow countryman/woman. It also does not explain why the gun is being pointed at very specific members of certain tribes and not the other.

The third narrative is about the role of Sudan in the civil war. Proponents of this narrative are keen on referring to past efforts by Khartoum to destabilise the southern region and even provide support to South Sudanese to carry out attacks in the region. A case in point is the support of the South Sudan Defence Forces (SSDF) by Khartoum between 1983 and 2005 (Young 2006:17). This alliance saw the SSDF, headed by among others Riek Machar, supporting garrisons of the Sudanese Armed Forces and protecting oil fields in the Northern part of South Sudan on behalf of the Khartoum government. In exchange the SSDF received technical and military assistance from the Arab North, including arms believed to have been instrumental in the 1991 Bor Massacre (Canadian Department of Justice 2014). Sudan and South Sudan have also been caught up in a dispute over the oil-rich Abyei region which both parties insist belongs to their side of the border (Born and Ravivn 2017:178). Some may argue that this dispute proves an ‘intention’ by Sudan to support the instability of South Sudan, but the counter-argument is that Sudan stands to benefit more from a peaceful South than from a South under civil war. One of the ways Sudan can benefit from the peace is that there will be good relations between the two countries, which in turn can lessen Juba’s support of rebel groups in Darfur and enable the three-year oil agreement between the two countries to proceed without any interference. Last but not least, Sudan’s involvement in the peace process can help rebuild the souring relations with international actors such as the European Union and the United States (Adam 2018).

In order to understand the South Sudan civil war, however, we need to look at more than just these three narratives. There are other relevant factors such as past events, ethnic identity and the role of individuals.

Manifestation of ethnicity in the South Sudan Conflict

At independence, South Sudan faced challenges similar to those faced by many other newly-independent countries of Africa. Competition for political power and differing ideologies among local leaders create a scenario where communities regroup within their ethnic cocoons in order to advance their cause (Cheeseman 2015:8–13). Such restructuring of communities have historical bases but are triggered by contemporary interests. Below we look at the nature in which ethnic rivalry manifests itself in the Sudan conflict.

Divisions within the SPLM

The Sudan People’s Liberation Movement was established in 1983 under the charismatic guidance of the late John Garang. Guided by the aim of realising a New Sudan, the SPLM led a rebellion against Khartoum in a bid to realise a more secularised state (Warner 2016:6–13). The SPLM drew its initial members from the South, but as the liberation quest gained momentum it incorporated some members from the North under the banner of liberating marginalised groups in the North (Barltrop 2010:3–5). Ethnically, the SPLM was from its inception a diverse organisation, but within that diversity, the Nuer and the Dinka were the majority by virtue of the sizes of their populations. They occupied polar positions within the organisation’s hierarchy – something that is still visible today (Kiranda et al. 2016:33).

As the liberation quest was on its course, the SPLM grappled with various challenges, ranging from organisational, internal and leadership to financial and ideological challenges (Janssen 2017:13). Finding solutions to these challenges became an uphill task for the SPLM leadership since these challenges were ethnicised – mainly as attempts by the dominant ethnic groups to find solutions that favoured their side. Thus, in the absence of a functioning united leadership, cracks emerged within the SPLM and signs of forthcoming splits began showing right from its inception. Along similar lines, Mamdani argues that cracks within SPLM provided a fertile ground for the continued conflict as the antagonised parties were confronted by two main issues: one was the equal ethnic representation of ethnic groups in the struggle for power, and two, the path in which the power would follow (Mamdani 2014). These divisions paved the way towards the subsequent rivalries that rocked SPLM from within.

The first split that occurred at the nascent stages of the liberation struggle (1984–1985) was more ideological and was anchored on the determination of the path the liberation struggle was to take. On one side, Akuot Atem Mayem and Gai Tut Yang were calling for an independent South Sudan, and on the other John Garang, William Nyuon Banyi, and Kerubino Kuanyin Bol led the side that advocated for what they termed a New Sudan which would be a more democratic, secular and pluralistic country. Both sides received support from diverse ethnic groups but there were undertones that the quest for an independent South Sudan was an idea of the Nuer while calls for a New Sudan resonated well with the Dinka (Kiranda et al. 2016). Although the claims and insinuations were muted, they triggered an unending slugfest between the two dominant ethnic groups and dimmed the possibilities of a peaceful South Sudan.

The second split, which served as a litmus test on the leadership of the SPLM, occurred in 1991 after Riek Machar joined forces with Lam Akol, a senior commander in the Sudan People’s Liberation Army (SPLA), to trigger a change of SPLM leadership. The two, together with others, called for the replacement of John Garang as the leader of the SPLM (Sørbø 2014:1). They accused Garang of establishing close ties with the Ethiopian government, which they regarded as a move that would stymie internal reforms within the SPLM (Johnson 2014). This attempt did not come to fruition, and Riek Machar led a splinter group in the formation of Sudan People’s Liberation Movement/Army-Nasir which continued to support the independence of the South from the North even though it received military and financial support from the government in Khartoum. Noteworthy, the confrontation between Riek Machar and John Garang has been viewed through an ethnic lens that pitted the Nuers against the Dinkas in a duel that has transformed South Sudan into a crucible of war.

The night of 15 December 2013 witnessed the 3rd split, which originated from the SPLM. Just after two years of independence the young nation was yet again embroiled in a conflict, and that has continued to date. Forces loyal to the president and those loyal to the vice-president were engaged in confrontations following weeks of intense succession politics within the SPLM Political Bureau (Johnson 2014:168). This time around it was President Salva Kiir accusing Machar of plotting a coup against his government just as the party was preparing its May 2013 SPLM National Convention which was supposed to discuss, among other issues, the party’s flag bearer in the 2015 presidential elections, the term limits of the chairperson of the SPLM, the Constitution and a code of conduct (Janssen 2017:12). An order to disarm members of certain communities within the presidential guard led to a mutiny that triggered revenge attacks of Dinka in Akobo and of Nuer at Bor (Johnson 2014:170). Although the alleged coup plotters were arrested, Riek Machar managed to escape from the country. But troops loyal to him continued with the conflict.

Ethnicity has remained an important variable in South Sudan’s politics. The tyranny of numbers enjoyed by dominant ethnic groups has become an important instrument of ascending to power. Ethnic mobilisations based on historical rivalries and attachments explain the composition of the warring parties in South Sudan. Strong ethnic loyalty combined with a political system that allows winners to dominate government positions and get a larger share of the national cake causes political stakes to be heightened to the extent of violence. It is also important to note that other factors like availability of arms amongst civilians, competition for available resources and the role of Sudan – underscored features in contemporary discourses – have aided the continuation of the conflict, but have not explained why it must always be a Dinka aiming a cannon at the Nuer and vice versa as it occurred in the Bor Massacre and other subsequent confrontations.

The Bor Massacre and its implications on the conflict

In 1991, two years after the fall of the Berlin wall, when the world was beginning to experience an aura of democratic peace after decades of intense rivalry between world powers, a massacre with devastating consequences occurred in Bor, the capital of Jonglei state (Wild, Jok and Ronak 2018:2–11). Located on the east of River Bahl al Jabal (White Nile), Bor was predominantly inhabited by pastoralist Nuers with pockets of Dinka communities. Years before the massacre, there had been a series of inter-ethnic cattle raiding episodes between the Nuers and the Dinkas in a bid to increase their herds. These raids were initially conducted by means of spears and well-orchestrated ambushes, but later, with an increase in the number of guns, firearms became the common tools of the trade. Regardless of the raiding methods, it is important to note that cattle are historical symbols of social status, and their products which are of high nutritional value are important sources of livelihood among South Sudanese communities (Glowacki and Wrangham 2015:349–350).

Prior to the massacre, there was a proliferation of arms among the civilians who had formed well-organised groups. While the Dinkas had the Titweng (a local militia), the Nuers had the ‘White Army’ that was originally formed to protect the cattle but upon gaining widespread success in their raids became an important asset in the political sphere (Young 2016). This came against the backdrop of visible rifts in the SPLM leadership that provided the avenue for Riek Machar to incorporate the Nuer white army members into SPLM-Nasir, and with the support of the Khartoum government in the North, SPLM-Nasir orchestrated one of the deadliest massacres in the history of South Sudan. According to Wild, Jok and Ronak (2018), Riek Machar who was then entangled in ideological differences with John Garang, mobilised over 20 000 members of the SPLM-Nasir to carry out an attack against the Dinkas in Bor in what came to be known as the Bor Massacre. It saw the death of over 2 000 people of Dinka origin and the destruction of properties as well as other atrocities (Wild, Jok and Ronak 2018). Even though Riek Machar offered an apology to the Dinkas in 2011 when he was the vice-president, it is without doubt that the massacre left an indelible footprint of loss on the lives of the Dinkas, and it has become a political tool that has been used against Riek Machar in his quest to ascend to the highest office in the land (Chol 2011:3).

It could be easy to argue that a focus on the historical rivalry between the dominant ethnic groups is simplistic and superficial and that this would reduce the ongoing feud solely into an ethnic conflict, as it is had already been labelled by segments of the international media. However, efforts to sustain an ethnic conflict narrative have been quickly countered by the argument that the South Sudan government was a representation of diverse ethnic groups and that even after the December 2013 crisis which saw a number of people arrested on the allegations of an attempted coup, the president did not spare those from his tribe (Pinaud 2014:192). Indeed, the ousted and the current vice-president belong to the Nuer and the president is from the Dinka, but the presence of people of diverse ethnic origins in the government cannot be construed to mean a representation of ethnic interests, since African societies have the propensity to bestow ethnic responsibilities on particular individuals whose voices not only become the voice of the ethnic groups but also symbols of ethnic unity. Therefore, any kind of humiliation that targets these ethnic kingpins becomes an outright humiliation to the ethnic groups they represent, who then, on behalf of their leaders, may endeavour to seek revenge.

Previous peace efforts

The first effort towards peace was spearheaded by IGAD with the support of Norway, the United Kingdom, and the United States in the course of 2014 (Taulbee, Kelleher and Grosvenor 2014:78) The committee had set an ambitious target of 5 March 2015 as the final deadline for achieving a peace deal in the Sudan conflict. However, the deadline passed without the target being realised. That same month sanctions were imposed on a number of individuals by the Security Council for their role in the conflict. Interestingly the two main protagonists, Kiir and Machar, were not included in the list of six individuals that were sanctioned. More pressure from regional and international players demanding an end to the senseless killing led to a new draft in June 2015 that was followed by the threat of further sanctions by the Security Council if the parties involved did not sign the agreement by 17 August 2015 (Foreign Policy 2015).

Two months after signing of the peace treaty the first obstacle emerged with the unilateral decision of President Kiir to establish 18 additional states above the then existing 10 states. This act was condemned, but a positive gesture from the President was made in December 2015 with the sharing of cabinet positions. By January 2016, the deadline for forming the Transitional Government of National Unity (TGNU) had been missed, indicating the slow progress in the implementation of the peace accord.

Finally, Riek Machar was appointed as the 1st Vice-President in February 2016 although he was still in exile at the time. Further security agreements such as the demilitarisation of the capital city, Juba, were also made. Late July 2016, an attack by alleged government forces on a UN-protected civilian camp threatened to shatter the peace process (Blanchard 2016:2). In the following weeks, pockets of fighting across the country were witnessed, and the UN Human Rights Commission published a report on 11 March 2016 asserting incidences of war crime that include sexual violence. The shaky agreement continued to hold, and Machar was able to return to Juba in April 2016 to take up the position of 1st Vice-President (Baker 2016:20–27). However, fighting broke out between government forces and those of Riek Machar, forcing him to flee the city once again, and marking the final collapse of the Transitional Government of National Unity.

De Vries and Schomerus (2017:333–340) explain that the collapse of the 2015 Agreement on the Resolution of the Conflict in the Republic of South Sudan (ARCSS) signed by the South Sudanese government, the international community and members of the opposition was a result of a lack of political goodwill by the government and the opposition, both of whom had more interest in the amount of power they would retain than in implementing the agreement (De Vries and Schomerus 2017:335). Indeed, the excessive attention given to the government and the opposition in the ongoing civil war has overshadowed genuine grievances that ordinary citizens of the country are facing and that can motivate them to take up arms and fight. This is further worsened by the perception that rebels are illegitimate groups challenging the sovereignty of the country and the opposition’s far-fetched claim that they represent genuine grievances of the citizens. De Vries and Schomerus do emphasise that unless there is a more comprehensive approach to peace in South Sudan, sharing of government slots may not offer a permanent solution.

The latest efforts to bring an end to the brutal conflict in South Sudan culminated with the signing of a peace agreement on 12 September 2018 in Addis Ababa. This marked the 12th time President Kiir and his fiercest rival Riek Machar have entered into a peace agreement since the conflict began. The unique feature of this new agreement is the involvement of two new actors, namely the presidents Bashir of Sudan and Museveni of Uganda. This is interesting in the sense that the former had been previously seen as a cause of the conflict, but under the new agreement he is seen as part of the solution. This new agreement, however, still failed to tackle the underlying cause of the conflict, which is ethnicity, as it facilitated sharing of government positions among the Nuer and Dinkas, so that the two dominant tribes were given the lion’s share at the expense of the smaller tribes. Already the conflicting parties have violated the cease-fire agreement with the most recent case taking place on 24 September 2018 when opposition and government forces clashed in Koch County in the Northern part of the Country. This appears to be a continued sign of dissatisfaction with the terms of the agreement – something that had earlier delayed the signing of the peace accord.

Findings

This paper has noted a number of issues that have either delayed peace or facilitated continued conflict. Of these, the following are the most important.

There seems to be an attitude of treating South Sudan not as an independent country, but as an amalgamation of ethnic groups with the dominant groups having their way. This is evident from the manner in which the peace agreements have been handled, so that there can only be a cease-fire when the dominant tribes are satisfied with the positions its members have been awarded.

Despite several peace agreements being signed, there are still weak support systems. The institutional bodies established to ensure smooth implementation of the peace agreements have often fallen short of their mandate due to operational and institutional challenges that hinder them from operating efficiently. Some of these institutions are: the Joint Monitoring and Evaluation Commission (JMEC), UNMISS, IGAD, the Ceasefire and Transitional Security Arrangement Monitoring Mechanism (CTSAMM) and the Regional Protection Force (RPF). There have been concerns over, inter alia, insufficient funding of these institutions, lack of leverage, insufficient command and control structures, and parallelisms.

Constant violation of cease-fire agreements is also a consistent observation in the South Sudan conflict. The key pillar of the peace agreements signed has been the Cessation of Hostilities Agreement (CoHA), yet in all the cases either one party has or both parties have violated this important clause. In some cases, the government even tried to prevent the reaching of cease-fire agreements. They refused to commit to a clause submitted during the second round of peace talks in September 2018 suggesting how those who violate peace would be punished, and they impeded the smooth operation of relief agencies by prolonging relief workers’ work permit processes (Reuters 2017a).

There is an absence of a serious commitment to end the conflict. Despite the devastating consequences of the South Sudan conflict, political leaders have failed to show goodwill to end the crisis (Keitany 2016:50). The main antagonists in the conflict bear political and moral responsibility to ensure that the life and dignity of the people of South Sudan are defended. On this however, they have failed. This extends to the regional and international actors involved in the peace process. The August 2018 peace agreement supported by IGAD has seen some of the countries lacking neutrality. Uganda and Sudan are said to be aligned with the interests of the government and opposition, respectively, while Ethiopia and Kenya are involved in diplomatic and economic rivalry which may play out in the peace process.

Complex military-politics relations in South Sudan are also visible and cause a hindrance to peace. There have been strong affiliations between soldiers and political elites, specifically from their ethnic groups, to whom they seem to pay more allegiance than to the state. This complex relationship is not new and began long ago, during and after the struggle for independence (Rolandsen and Kindersley 2017:9–12). The ever visible military influence in state affairs has been further supported by the laxity of previous peace agreements to accommodate non-state actors in the transition period, and to train ethnic militias adopted into the national army for their new role. More importantly, both government and opposition military forces hold extreme positions – the latter calling for the removal of the president and the opposing the inclusion of opposition political leaders in the government.

Recommended approach to peace

The findings of this paper indicate that sustainable peace in South Sudan cannot be realised until key factors are addressed. These include an inadequate sense of nationalism due to the presence of ethnic identities stronger than national identity; a lack of strong institutions to ensure full implementation of peace agreements; a lack of neutral security forces that do not take sides in the conflict; and a lack of political will to achieve peace. The recommendations below attempt to fill these gaps in the following ways:

Providing President Salva Kiir, Riek Machar and other key figures involved in the current conflict a negotiated exit from the political sphere of South Sudan. This is because they hold the highest responsibility for the on-going conflict since they are at the top of the command chain and have failed to ensure that their troops adhere to the International Law of Armed Conflict. Their exit will have to be negotiated, with due consideration to procedure and timing. This will help overcome fears of a possible repeat of the crisis as happened in Iraq, Libya and Yemen. Parties to be involved in this process should include IGAD, the East African Community, the African Union, the United Nations General Assembly, and the Security Council.

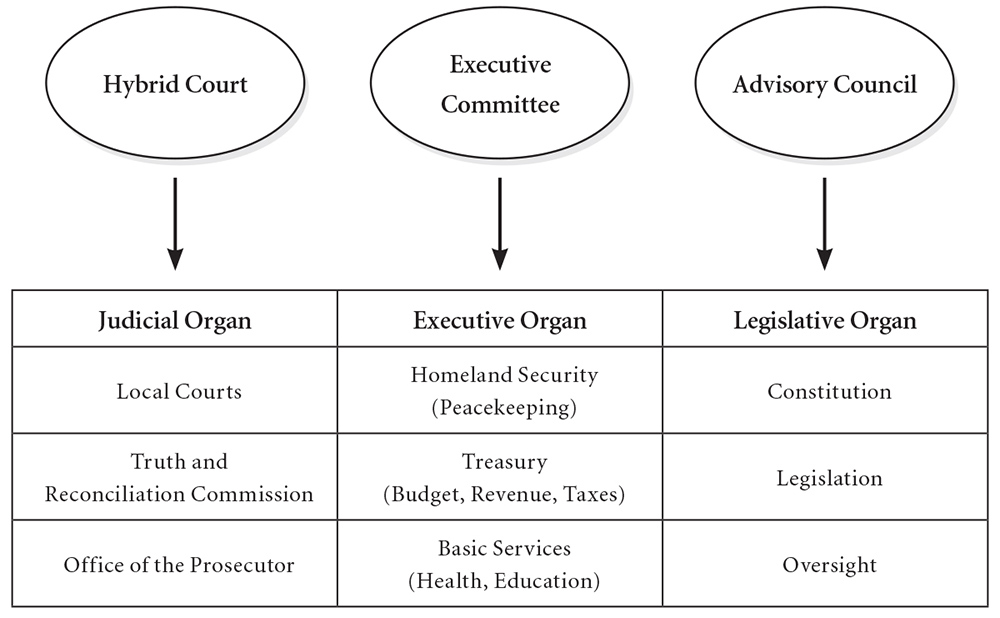

Establishing a temporary Transitional Authority under a Security Council Resolution that will include nominees from the political, economic, professional, diaspora, religious and cultural spheres of South Sudan and the international community. This authority may adopt a three-organ structure as suggested in figure 3 below in order to cover the important dimensions of the society. First is a Hybrid Court, consisting of foreign and local judges as well as a prosecutor, acting as the judicial arm with a specific mandate to oversee the activities of a Truth and Reconciliation Commission and the local courts. Second is an Executive Committee that will oversee the day-to-day operations in the country. It will be comprised of a department of Homeland Security consisting of a strong peacekeeping force mandated to recruit, train and restructure the country’s security organs: a department of Treasury that will deal with issues of financial management and acquisition; and a department of Social Services that will temporarily reform the health, education and basic infrastructure sectors. The third organ is an Advisory Council that will act as a legislative organ and will be tasked with drafting a new constitution within a specified period, passing basic laws and approving government expenditure as well as conducting oversight.

Structure of the Proposed Transitional Authority

Initiating the cessation of hostilities and a disarmament process in order to end the widespread supply of arms to civilians. Any party involved in violence after the declaration of cessation of hostilities should face trial under existing laws before retaliation by the other parties takes place.

Drafting a new constitution for the country that will require the establishment of a political and economic system that guarantees each and every South Sudanese equity and equality. The politics of winner takes all should be ruled out, while the separation of powers between the executive, judiciary, legislature and the local government must be strengthened. Division of labour among the various security forces must be emphasised so that they are divorced from politics.

Conclusion

The recommended model of a transitional authority is not a new concept and it will not be the first time a country is put under international custody. Yossi Shain and Juan J. Linz have written extensively regarding provisional governments, and they divide them into three categories: Power-sharing provisional governments, Incumbent provisional governments, and International provisional governments. Our recommendation is a hybrid provisional government that will see more international actors and some locals involved in managing the country during the transition period. We hope for reasonable success, as witnessed in cases as the following: the Provisional Government of Spain (1868–1871), the Caretaker Government of Australia (1901), the Provisional Government of Ireland (1922), the Interim Government of India (1946–1947), the Provisional Revolutionary Government of the Republic of South Vietnam (1969–1976), the Transitional Government of the Democratic Republic of the Congo (2003–2006), the United Nations Transitional Authority in Cambodia (1992–1993), and provisional governments in several other countries .

These recommendations come against the backdrop of already failed attempts to bring peace to South Sudan through the sharing of government positions between the government and the opposition. This experience has in fact further worsened the situation, since new political players understand that in order to have a place at the negotiating table, one must first prove one’s worth through use of violence and blackmail. The new recommendations recognise that the conflict in South Sudan is deeply rooted and cannot be solved overnight through a power-sharing agreement and a handshake. Such an approach may take longer but has a better chance for finding lasting solutions to the challenges in South Sudan. South Sudan’s independence came about under unique circumstances that differed from those in African countries with fair social, economic and education infrastructures. As a justification for the above-recommended approach, the following were taken into consideration.

First, the recommended form of hybrid approach borrows from previously implemented strategies in post-conflict countries such as Rwanda (post-1994), South Africa (1994), Kenya (2007), Cambodia (1970–1973), and Namibia (1988–1990), and the Democratic Republic of the Congo, where the United Nations established a tutelage to prepare political leaders (2003). Some of these countries have been under international trusteeship; others have adopted either an international legal system to try perpetrators of past violence, or a truth justice and reconciliation commission. Secondly, there is the consideration that this proposal could help to address the peace vs justice dilemma that keeps resurfacing when discussing peace in South Sudan. The recommendation does offer a smooth transition after the exit of the current set of political elites. It proposes a negotiated agreement that should avoid a catastrophic outcome as was seen in Iraq during the exit of Saddam Hussein and in Libya with the violent death of Muammar Gaddafi.

The truth, justice and reconciliation process will give South Sudanese a platform to dialogue openly about their grievances and come to a consensus on what needs to be done to achieve justice in a manner that does not elicit violence. A further merit of this approach is that it should tackle deep-rooted structural weaknesses of the state by recommending a new system of government, which is compatible with the social features of the country and not just a power-sharing deal between the warlords. If a proportional system of representation is adopted, it will get rid of the ‘winner takes all’ mentality that affects not just South Sudan but also many African countries. The new constitution, implemented with the assistance of UN-deployed forces, should help restructure and give a new meaning and philosophy to the security organs of the country. When everything is considered, what the people of South Sudan need, is an inclusive, unbiased and honest approach to peace – an approach that is not surrounded by political and economic ambitions of the leaders, but one that uproots the grievances from the bottom.

Sources

- ACLEDP (Armed Conflict Location and Event Data Project) 2018. South Sudan analysis. Available from: <https://www.acleddata.com/dashboard/#728> [Accessed 9 April 2018].

- Adam, Ahmed H. 2018. Why is Omar al-Bashir mediating South Sudan peace talks? Al Jazeera, 5 Jul 2018. Available from: <https://www.aljazeera.com/indepth/opinion/omar-al-bashir-mediating-south-sudan-peace-talks-180705134746432.html> [Accessed 15 April 2018].

- Adams, Karen Ruth 2000. State survival and state death: International and technological contexts. Ph.D. dissertation, University of California, Berkeley.

- African Union 2014. Final Report of the African Union Commission of Inquiry on South Sudan. Addis Ababa, 15 October 2014. Available from: <http://www.au.int/en/auciss> [Accessed 23 May 2018].

- Baker, Aryn 2016. War crimes: Slaughter and starvation haunt a broken South Sudan. Time, 187 (20) (30 May), pp. 20–27.

- Ballentine, Karen and Heiko Nitzschke 2005. The political economy of civil war and conflict transformation. Berghof Research Centre for Constructive Conflict Management, Berlin. Available from: <http://www.berghof-handbook.net/articles/BHDS3_BallentineNitzschke230305.pdf> [Accessed 9 April 2018].

- Bariyo, Nicholas 2014. South Sudan’s debt rises as oil ebbs. Wall Street Journal, 5 August. Available from: <https://www.wsj.com/articles/south-sudans-debt-rises-as-oil-ebbs-1407280169> [Accessed 21 June 2018].

- Barltrop, Richard 2010. Leadership, trust and legitimacy in Southern Sudan’s transition after 2005. Global Event Working Paper, presented at the ‘Capacity is development’ Global event, New York, 2010, sponsored by the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP). Available from: <http://www.undp.org/content/dam/aplaws/publication/en/publications/capacity-development/drivers-of-change/leadership/leadership-trust-and-legitimacy-in-southern-sudan-transition-after-2005/Leadership_trust%20and%20legitimacy%20in%20Southern%20Sudan%20transition%20after%202005.pdf> [Accessed 23 May 2018].

- Blackings, Mairi J. 2016. Why peace fails: The case of South Sudan’s Agreement on the Resolution of the Conflict in South Sudan. Nairobi, Friedrich Ebert Stiftung (Foundation).

- Born, Gary B. and Adam Ravivn 2017. The Abyei arbitration and the rule of law. Harvard International Law Journal, 58 (1), pp. 177–224.

- Canadian Department of Justice 2014. Armed Conflicts Report – Sudan. Available from: <file:///V|/vll/country/armed_conflict_report/Sudan.htm> [Accessed 9 April 2018].

- Cheeseman, Nic 2015. Democracy in Africa: Successes, failures, and the struggle for political reform. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press.

- Chol, Agereb Leek 2011. 20 years apology: A political campaign for Dr. Riek Machar Teny – A case of ‘Why Garang Must Go Now’ is now recanted. Available from:

<https://paanluelwel2011.files.wordpress.com/2011/10/dr-riek-political-apology.pdf>

[Accessed 16 May 2018]. - Collier, Paul, Anke Hoeffler and Måns Söderbom 2004. On the duration of civil war. Journal of Peace Research, 41 (3), pp. 253–273.

- De Soysa, Indra 2002. Paradise is a bazaar? Greed, creed, and governance in civil war, 1989–99. Journal of Peace Research, 39 (4), pp. 395–416.

- De Vries, Lotje and Mareike Schomerus 2017. South Sudan’s civil war will not end with a peace deal. Peace Review, 29 (3), pp. 333–340.

- Doyle, Michael W. and Nicholas Sambanis 2000. International peacebuilding: A theoretical and quantitative analysis. American Political Science Review, 94 (4), pp. 779–801.

- Fearon, James D. and David D. Laitin 2003. Ethnicity, insurgency, and civil war. American Political Science Review, 97 (1), pp. 75–90.

- FEWSN (Famine Early Warning Systems Network) 2016. Food security outlook update: Staple food prices increasing more rapidly than expected. 16 April 2016. Available from: <http://fews.net/east-Africa/south-Sudan/food-security-outlook-update/April-2016> [Accessed 22 August 2018].

- Foreign Policy 2015. U.S. threatens South Sudan with sanctions … again. 24 February 2015. Available from: <https://foreignpolicy.com/2015/02/24/u-s-threatens-south-sudan-with-sanctions-again/> [Accessed 22 December 2017].

- Glowacki, Luke and Richard Wrangham 2015. Warfare and reproductive success in a tribal population. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 112 (2), pp. 348–353.

- IMF (International Monetary Fund) 2017. South Sudan: 2016 Article IV Consultation-Press Release; Staff Report; and Statement by the Executive Director for South Sudan. IMF Staff Country Report No. 17/73, 23 March 2017. Washington, IMF. Available from: <https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/CR/Issues/2017/03/23/South-Sudan-2016-Article-IV-Consultation-Press-Release-Staff-Report-and-Statement-by-the-44757> [Accessed 23 May 2018].

- Janssen, Jordy 2017. South Sudan: Why power-sharing did not lead to political stability. Unpublished M.A. thesis, University of Leiden.

- Johnson, Douglas H. 2014. The political crisis in South Sudan. African Studies Review, 57 (3), pp. 167–174. (doi:10.1017/asr.2014.97)

- Jok, Jok Madut 2015. The paradox of peace in Sudan and South Sudan: Why political settlements failed to endure. Inclusive Political Settlements Papers, 15, September. Berlin, Berghof Foundation.

- Keitany, Phillip 2016. The African Union Mission In South Sudan: A case Study of South Sudan. Unpublished M.A. thesis, University of Nairobi.

- Kiranda Yusuf, Mathias Kamp, Michael B. Mugisha and Donnas Ojok 2016. Conflict and state formation in South Sudan: The logic of oil revenues in influencing the dynamics of elite bargains. Journal on Perspectives of African Democracy and Development, 1 (1), pp. 30–40.

- Knopf, Katherine A. 2016. Ending South Sudan’s civil war. Council Special Report No. 77. New York, Council on Foreign Relations, Center for Preventive Action.

- Krasner, Stephen D. 1999. Sovereignty: Organized hypocrisy. Princeton, Princeton University Press.

- Mamdani, Mahmood 2014. South Sudan: No power-sharing without political reform. New Vision newspaper, 18 February.

- Martell, Paul 2016. South Sudan is dying, and nobody is counting. News24 France, 10 March. Available from: <https://www.news24.com/Africa/News/south-sudan-is-dying-and-nobody-is-counting-20160311-4> [Accessed 13 July 2018].

- Mercy Corps 2018. Quick facts: What you need to know about the South Sudan crisis. February 2018. Available from: <https://www.mercycorps.org/articles/south-sudan/quick-facts-what-you-need-know-about-south-sudan-crisis> [Accessed 9 April 2018].

- O’Brien, Adam 2009. Shots in the dark: The 2008 South Sudan civilian disarmament campaign. Geneva, Small Arms Survey.

- OHCHR (Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights) 2013. Pillay urges South Sudan leadership to curb alarming violence against civilians. 24 December. Available from: <https://reliefweb.int/report/south-sudan-republic/pillay-urges-south-sudan-leadership-curb-alarming-violence-against> [Accessed 25 April 2018].

- Ottaway, Marina and Mai El-Sadany 2012. Sudan: From conflict to conflict. Washington, D.C., Carnegie Endowment for International Peace.

- Pinaud, Clemence 2014. South Sudan: Civil war, predation and the making of a military aristocracy. African Affairs, 113 (451), pp. 192–211.

- Reuters 2014. South Sudan oil state capital divided, says government. February 20. Available from: <https://www.reuters.com/article/us-southsudan-unrest/south-sudan-oil-state-capital-divided-says-government-idUSBREA1J0DK20140220> [Accessed 9 April 2018].

- Reuters 2017a. South Sudan drops plan for $10,000 work permit fee for aid staff. 3 April. Available from: <https://www.reuters.com/article/us-southsudan-workers-permit-idUSKBN1751AI> [Accessed 12 July 2018].

- Reuters 2017b. South Sudan needs $1.7 billion humanitarian aid in 2018. December 21. Available from: <https://www.reuters.com/article/us-southsudan-unrest/south-sudan-needs-1-7-billion-humanitarian-aid-in-2018-idUSKBN1E71BK> [Accessed 16 May 2018].

- Reuters 2018. U.N. Security council imposes an arms embargo on South Sudan. 20 July. Available from: <https://www.reuters.com/article/us-southsudan-unrest-un/u-n-security-council-imposes-an-arms-embargo-on-south-sudan-idUSKBN1K3257> [Accessed 9 April 2018].

- Rolandsen, Øystein H. 2015. Small and far between: Peacekeeping economies in South Sudan. Journal of Intervention and Statebuilding, 9 (3), pp. 353–371.

- Rolandsen, Øystein H. and Nicki Kindersley 2017. South Sudan: A political economy analysis. Oslo, Norwegian Institute of International Affairs (NUPI).

- Ross, Michael 2002. Natural resources and civil war: An overview with some policy options. Draft report prepared for conference on ‘The Governance of Natural Resources Revenues’ sponsored by the World Bank and the Agence Francaise de Developpement, Paris, December 9–10.

- Sachs, Jeffrey D. and Andrew M. Warner 2001. The curse of natural resources. European Economic Review, 45 (4–6), pp. 827–838.

- Blanchard, Lauren P. 2016. Conflict in South Sudan and the challenges ahead. Congressional Research Service. Available from: <https://fas.org/sgp/crs/row/R43344.pdf> [Accessed 6 April 2018]

- Sefa-Nyarko, Clement 2016. Civil war in South Sudan: Is it a reflection of historical secessionist and natural resource wars in ‘Greater Sudan’? African Security, 9 (3), pp. 188–210.

- Sørbø, Gunnar M. 2014. Return to war in South Sudan. Policy Brief. Norwegian Peacebuilding Resource Centre. Available from: <http://noref.no/var/ezflow_site/storage/original/application/dfe9c9db13050b38a2a5c-73c072af1e.pdf> [Accessed 15 September 2018].

- Stedman Stephen John, Donald S. Rothchild and Elizabeth M. Cousens 2002. Ending civil wars: the implementation of peace agreements. Boulder, CO, Lynne Rienner.

- Sudan Tribune 2016. IMF warns of further deteriorating economy in South Sudan. 3 June. Available from:<http://www.sudantribune.com/spip.php?article59164> [Accessed 13 April 2018].

- Sudan Tribune 2017. South Sudanese pound loses further value against U.S. dollar. 13 April. Available from:<http://www.sudantribune.com/spip.php?article62178> [Accessed 13 April 2018].

- Taulbee, James L., Ann Kelleher and Peter Grosvenor 2014. Norway’s peace policy: Soft power in a turbulent world. London, Palgrave Macmillan.

- The Star 2018. Salva Kiir, Riek Machar sign peace agreement in Khartoum. June 27. Available from: <https://www.the-star.co.ke/news/2018/06/27/salva-kiir-riek-machar-sign-peace-agreement-in-khartoum_c1778869> [Accessed 13 April 2018].

- Thomson, Janice E. and Stephen Krasner 1989. Global transactions and the consolidation of sovereignty. In: Czempiel, Ernst Otto and James N. Rosenau eds. Global changes and theoretical challenges: Approaches to world politics for the 1990s. Lexington, MA, Lexington Books. pp. 195–219.

- UNSC (United Nations Security Council) 2013. Security Council resolution 2132, South Sudan and Sudan, S/RES/2132, 24 December 2013. New York, UNSC.

- UNHCR (United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees) 2018. South Sudan Situation: UNHCR Regional Update. Available from: <https://reliefweb.int/report/south-sudan/south-sudan-situation-unhcr-regional-update-1–31-december-2017> [Accessed 13 April 2018].

- UNOCHA (United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs) 2013. South Sudan crisis: Situation report, 26 December. Report Number 4.

- Waal, Alex D. 2014. When kleptocracy becomes insolvent: Brute causes of the civil war in South Sudan. African Affairs, 113 (452), pp. 347–369.

- Walt, Stephen M. 1998. International relations: One world, many theories. Foreign Policy, (110), pp. 29–46.

- Warner, Lesley Anne 2016. The disintegration of the Military Integration Process in South Sudan (2006–2013). Stability: International Journal of Security and Development,

5 (1), art. 12, pp. 1–20. Available from: <http://dx.doi.org/10.5334/sta.460> [Accessed 13 April 2018]. - Wild, Hannah, Jok Madut Jok and Patel Ronak 2018. The militarization of cattle raiding in South Sudan: How a traditional practice became a tool for political violence. Journal of International Humanitarian Action, 2018 (3:2), pp.1–11.

- Young, John 2006. The South Sudan Defence Forces in the wake of the Juba Declaration. Geneva, Small Arms Survey (Graduate Institute of International and Development Studies).

- Young, John 2016. Popular struggles and elite co-optation: The Nuer White Army in South Sudan’s Civil War. Geneva, Small Arms Survey (Graduate Institute of International and Development Studies).