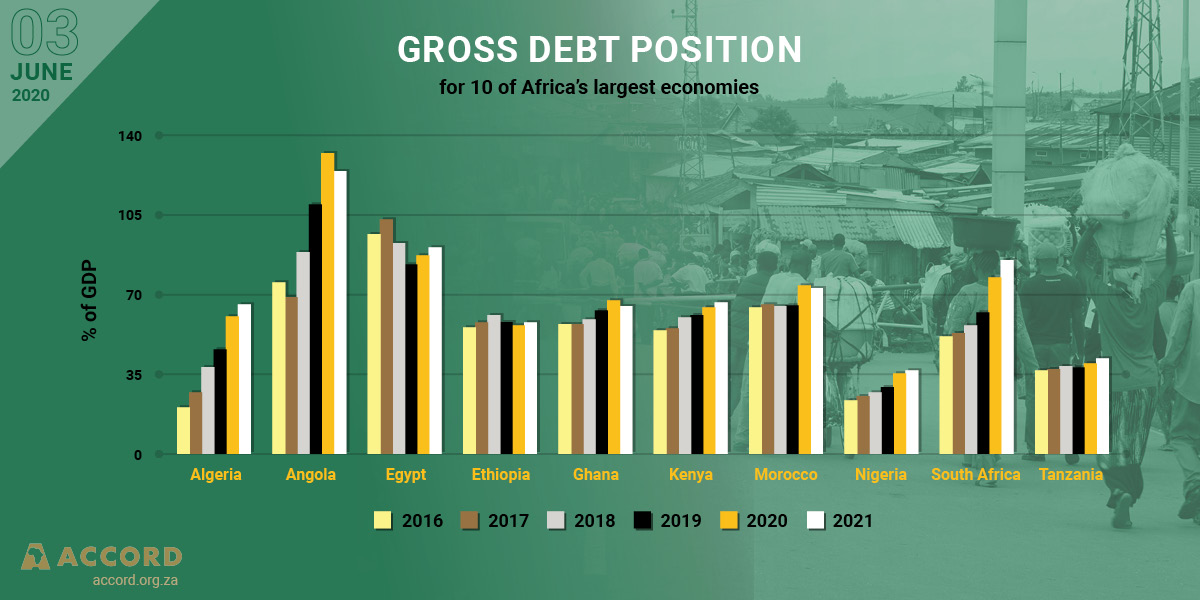

Prior to the COVID-19 outbreak, Africa was already facing a looming debt crisis. According to the World Bank, the total debt for sub-Saharan Africa climbed nearly 150% to US$583 billion between 2008 and 2018, and already led many in this pre-COVID context to issue warnings of instability, as average public debt increased from 40% of GDP in 2010 to 59% in 2018.

A recent Africa’s Pulse report found that COVID-19 is likely to drive sub-Saharan Africa into its first recession in 25 years, with economic growth in the region declining from 2.4% in 2019 to between -2.1% and -5.1% in 2020. The effect of this will be compounded by a looming food security crisis, as a result of agriculture production decreasing between 2.6% and 7%. While the pandemic is placing extreme strain on even the most well-resourced health systems; for Africa, COVID-19 could be a “national security crisis first, an economic crisis second and a health crisis third”.

In the face of the current crisis, calls have been made for a familiar but more proactive approach to dealing with Africa’s debt, which since the outbreak of COVID-19 has seen many countries surpassing recent historical highs and the 60% debt-to-GDP threshold prescribed by the African Monetary Co-operation Program (AMCP) for developing economies. However, to action these calls will require a paradigm shift in the way we value debt in economic policy and in terms of public spending. To begin, the former Executive Secretary of the UN Economic Commission for Africa, Carlos Lopes, said that “…the stimulus that we need to envisage must be comparable to what we are seeing in the economies of the north. That means a stimulus package of at least 5% of GDP, either in the form of capital mobilisation, or in the form of debt relief or restructuring, or support for the social sectors.”

African needs a stimulus package of at least 5% of GDP, either in the form of capital mobilisation, or in the form of debt relief or restructuring, or support for the social sectors. @LopesInsights

Tweet

The African Union’s lead

The AU has led the charge with regard to ensuring Africa’s economic viability during and after COVID-19. Ahead of the Group of 20 (G20) Leaders’ Summit on 26 March 2020, President Cyril Ramaphosa of South Africa, in his capacity as Chairperson of the AU, convened a teleconference with the Bureau of the African Union Heads of State and Government. At this meeting, the Bureau urged G20 countries to “…provide an effective economic stimulus package that includes relief and deferred payments” and “…called for the waiver of all interest payments on bilateral and multilateral debt, and the possible extension of the waiver to the medium term…” to provide immediate fiscal flexibility and liquidity to African governments.

In a virtual meeting of the G20 on 15 April, it was agreed to suspend official debt obligations until 2022. It is estimated that this ‘debt standstill’ could postpone US$12 billion in payments this year, and its total temporary relief could amount to more than US$20 billion. While this is undoubtedly a win for the AU, there is still significant ground to be made, and this concession will only cover a quarter of the debt service payments that Africa is due to make in 2020. Moreover, the debt principal and interest will have to be paid when payments restart, and the deal offers no respite to African countries defined as lower-middle income, such as Côte d’Ivoire, Ghana, Kenya and South Africa.

What are the next steps?

While debt cancellations are unlikely to reach a consensus among G20 members and international financial institutions in the required time frame, what is increasingly probable is the allocation of the International Monetary Fund’s (IMF) Special Drawing Rights (SDRs). SDRs are a form of global money issued by the IMF that are held in the foreign reserves of its member states, which can be traded or transferred to another country’s bank to boost liquidity. Indeed, European political leaders, including French President Emmanuel Macron and German Chancellor Angela Merkel, have joined their African counterparts to urge the IMF to “…decide immediately on the allocation of special drawing rights” to “…provide additional liquidity for the procurement of basic commodities and essential medical supplies”.

The issuing of SDRs, however, is not without its detractors. During an IMF and World Bank meeting, United States Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin pushed back against any plan involving SDRs.

African ministers have also approached Beijing to negotiate some relief for payments servicing the US$140 billion the continent owes to China and its biggest companies.

Other key stakeholders are Africa’s private creditors. Much of Africa’s pre-COVID debt was accrued on international financial markets through eurobonds that were taken on in 2018 and 2019. As of March 2019, outstanding African sovereign eurobonds reached US$102 billion. Negotiations will need to be opened with these creditors to avoid defaults that could quickly lead to many countries becoming ‘locked out’ of markets.

Soon after the announcement of this debt standstill, the Chairperson of the AU appointed four Special Envoys to solicit financial support for Africa’s efforts from G20 countries, international organisations and donor communities, as well as African business communities. These Special Envoys are Ngozi Okonjo-Iweala of Nigeria, Donald Kaberuka of Rwanda, Tidjane Thiam of Senegal and Trevor Manuel of South Africa. This team’s goal is to secure debt relief of US$44 billion, a generalised suspension of interest payment for all of Africa’s economies, and a stimulus package of US$100-150 billion.

At the recent virtual roundtable discussion hosted by the United Nations on financing for development in the era of COVID-19 and beyond, President Ramaphosa re-emphasised that African states need a fair and equitable regime to enable countries to respond to the immediate health and humanitarian crisis and to initiate economic recovery. This will require the World Bank, the IMF, the African Development Bank and other regional institutions to use all their available instruments to help build Africa’s resilience against the health crisis and provide relief for its communities and their economies.

Africa needs a fair and equitable debt regime to help build Africa’s resilience against the health crisis and provide relief for its communities and their economies. @CyrilRamaphosa @AUChair2020

Tweet