Images of riots over food shortages during the COVID-19 pandemic in several African countries; security forces being deployed to “restore order;” reports of patients escaping testing centres, and quarantined citizens escaping isolation facilities, all point to the missing link in COVID-19 containment measures, which is the absence of an adequate understanding of “the human factor.” These incidents provide a stark reminder that, as we have learned from the Ebola crisis in West Africa and elsewhere, COVID-19 containment strategies will fail unless they sufficiently involve communities in their design and implementation.

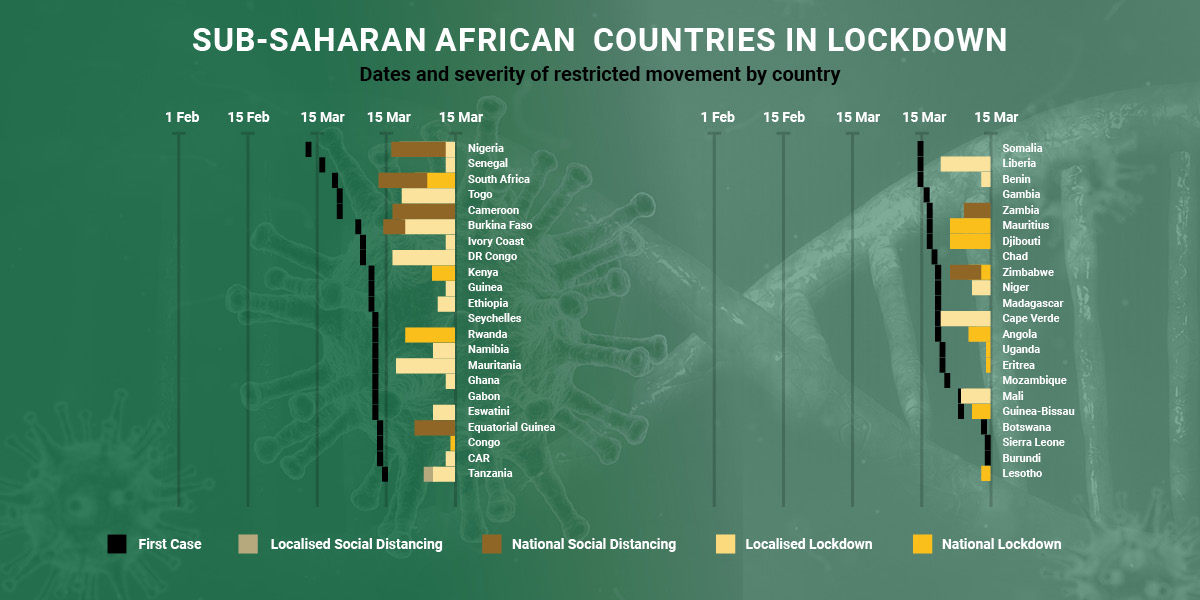

African countries have put in place a range of measures to contain the spread of the pandemic, ranging from lockdowns, curfews, banning of public gatherings, closure of schools and limiting unnecessary movement. As important as these measures are, governments should not forget that people are at the centre of this crisis. Thus, people must be involved and engaged in making decisions on what strategies work best for them in not only safeguarding their health, but also securing their livelihoods. Unfortunately, many African governments treat their citizens as subjects and consumers of policies, rather than as partners who can help to shape and tailor these responses.

Already, there are reports of security forces and police using excessive force against citizens. In South Africa, police had running battles with citizens who wanted to buy basic commodities in the middle of a lockdown. In Mutare, Zimbabwe, police confiscated and burned agricultural produce belonging to small-scale farmers and vendors, to close down local markets. On the first days of the curfew in Mombasa, Kenya, there were reports of police teargassing people waiting for a ferry. These kinds of heavy-handed responses are likely to further undermine the trust between state and society, at a time when the success of containing the pandemic is dependent on the voluntary cooperation of people and communities.

Building trust and engaging people and communities in the design and implementation of the containment measures is not an overtly costly exercise, all it needs is commitment. First, there is need to establish, support and work with existing local structures for governance. In Sierra Leone and Liberia, during the Ebola crisis which affected West Africa from 2014-2016, Local Community Liaison teams (LCLTs) engaged with the community through public meetings and radio shows to improve the acceptability and compliance of the preventive measures. Evidently, Liberia has learned about the importance of citizen participation from its management of the Ebola virus. In April 2020, Liberia launched the National Youth Taskforce Against COVID-19, recognizing that young people have a role to play in outreach, education and mitigation efforts.

Second, there needs to be a seamless collaboration between political leaders, government officials, the security sector and civil society. South Africa is now engaging civil society in its COVID-19 containment strategy. It is working closely with the C-19 People’s Coalition, a platform of over 250 civil society organisations. Members of the coalition share knowledge, lessons and help to monitor and mitigate against unintended consequences of the pandemic, including gender-based violence, crime, discrimination, hunger and food insecurity and others.

Third, governments can utilize digital technologies and social media to directly communicate with people to share information and counter rumours and myths. The African Union’s African Centre for Diseases Control (AfricanCDC) is, for example, using innovative messaging services to ensure credible information on COVID-19 is available to people all over Africa using local languages. Using digital technologies and social media, the African CDC project is not only aimed at tackling misinformation, but it will also combat stigmatization

Finally, governments need to address the socio-economic impact of COVID-19. Many African governments such as Kenya, Rwanda and South Africa have announced social protection measures. In Zimbabwe, for example, the government is working with the Grain Millers Association to ensure that people have access to mealie-meal despite the lockdown. African Governments need to factor in the reality that families living in informal settlements, and those working in the informal economy, must work daily to afford a meal. For example, South Africa has re-opened “spaza shops” (small tuck-shops) and now allows fruit and vegetable vendors in high-density suburbs to operate so that they can continue to earn an income. Other governments can borrow a leaf from this example, by allowing small-scale traders to operate, while adhering to the public health measures.

As African governments try to navigate COVID-19, the use of purely medical and epidemiological approaches will not be effective. The voices, needs and livelihoods of people and communities must remain at the centre. COVID-19 will be more successful contained by an approach that prioritizes care and emphasizes voluntary and collaborative behavioural change rather than one that relies on enforcement and fear.

Currently, Martha Mutisi is a Senior Programme Officer with the International Development Research Centre (IDRC)’s Governance and Justice Programme. Based in IDRC’s East and Southern Africa Regional Office (ESARO), Martha oversees research projects in the region, focusing on promoting youth resilience to violence and vulnerability; promoting women’s roles in peace and security; strengthening women’s leadership in education and science systems; and addressing the impacts of forced migration on local governance, and among others.

A recipient of the Fulbright Fellowship and Josh Weston Fellowship, Martha Mutisi Martha has more than 15 years of experience in research, training, policy influence and program design, implementation & management in peace, security, governance and development. Mutisi has worked with diverse stakeholders, including national & local governments, traditional and religious leaders, regional organisations, civil society institutions, women and youth groups. Previously (from September 2010 – October 2013), Martha worked with the African Centre for the Constructive Resolution of Disputes (ACCORD); first as Senior Researcher in the Knowledge Production Department and then as Manager for the Interventions Department.

Before joining IDRC in November 2015, Martha Mutisi also briefly worked with UN Women (Zimbabwe Country Office) as a Programme Specialist on Gender, Peace and Security. Martha holds a PhD in Conflict Analysis and Resolution from George Mason University (USA), a Master’s in Peace and Governance from Africa University, a Master’s in Sociology and Anthropology and Bachelor’s Degree Honours in Sociology from the University of Zimbabwe.