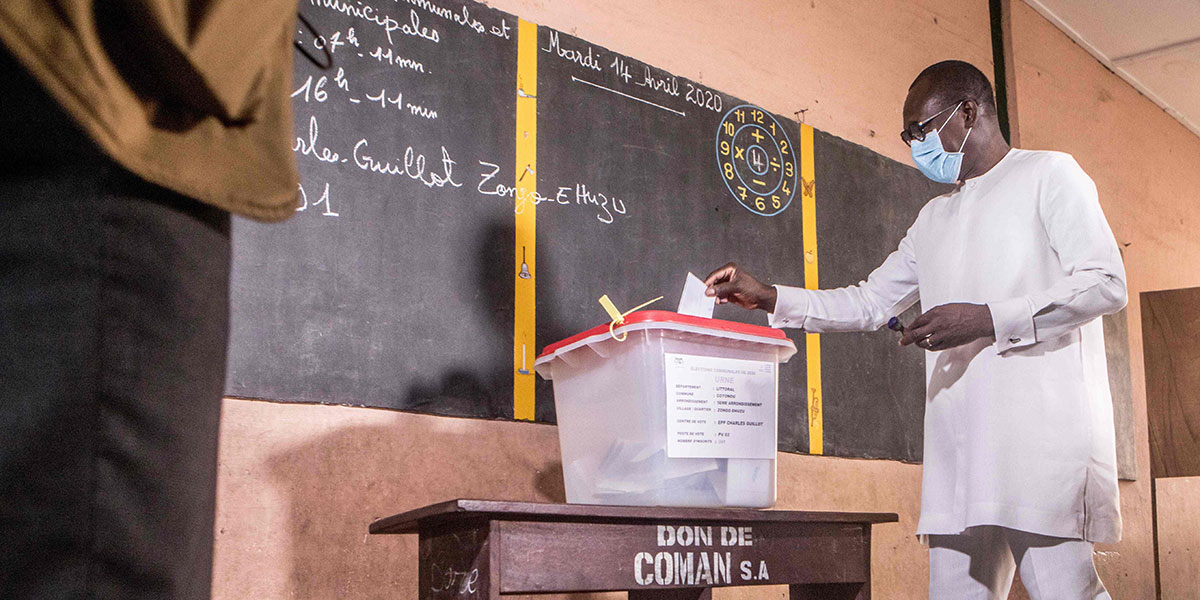

There are more than twenty countries scheduled to hold elections in Africa in 2020. This raises complex and difficult questions such as do we encourage countries to proceed with elections at the risk of increasing the spread of COVID-19, or do we ask countries to postpone elections at the risk of creating potential unintended constitutional and/or political tensions.

Generally, electoral processes are already an involved endeavor! Electoral processes include campaigns by a multitude of political parties, the registration of voters and the preparation of voter’s rolls, civic and voter education, as well as mass gatherings in the form of political party rallies. All of these election processes have been affected by the spread of COVID-19 on the continent and the measures implemented to contain the spread of the virus. Whichever way we look at this complex situation, we cannot deny the fact that the disruptions to the normal activities relating to electoral planning processes caused by COVID-19, force us to consider a number of challenges.

Brigalia Bam: The COVID-19 measures have placed a responsibility on all of us to ensure that the strides that various African countries had made to consolidate their democracies by holding regular, transparent, and free elections are not reversed.

Tweet

Firstly, we need to think about the financial implications of conducting elections in the context of various restrictions and COVID-19 social distancing measures. There are a number of African countries, including some who are due to hold elections in 2020, who rely on external financial support for a fully-fledged electoral budget. However, most countries in both the developing and developed world have had to re-prioritize their budgets due to COVID-19. This then raises the question of whether all the countries scheduled to hold elections in 2020 will have the financial resources to prepare and hold a successful election in a year plagued by a pandemic?

Secondly, COVID-19 has brought to the fore the question of deploying and effectively using technology – such as electronic voting – during elections in Africa. While this is indeed an important consideration to explore , we must also reflect on whether all our citizens in both rural and urban areas, given the unequal access to technology and the varying connectivity issues across the continent, will be afforded an opportunity to exercise their rights without the hindrance of issues caused by technology.

Thirdly, pre-election phases involve large gatherings of political party supporters, with politicians travelling the length and breadths of their countries in order to solicit and build support for their parties. These would be some of the factors during a pre-election and campaign period which would be severely affected by COVID-19 prevention measures. Social distancing measures also restrict the opportunity for parties to physically mobilize large groups of supporters. However, they would now have to concentrate on and resort to online and social media platforms, as well as other forms of technologically driven campaign techniques. The implications of such forms of campaigning, within a continent filled with serious urban and rural divide, is something that cannot be overlooked.

The COVID-19 containment measures, including international and national travel restrictions, border closures, social distancing, and quarantine, affects the existing approaches to preparing and deploying international observer missions. Those of us who have spent most of our r lives working on election related issues, and who have come to consider international observer missions as one of the contributors to credible elections, and mitigating disputes where they may occur, are now called upon to engage in introspection. Do we ask Member States to revise their electoral calendars so as to allow for both international and national observation that is suited to measures aimed at curbing COVID-19? How many of our sub-regional and regional mechanisms will be able to afford the increased cost of conducting observations under COVID-19? The increase in cost could result in, for instance, longer deployment of observers to allow for quarantine, and the need for more vehicles to enable observers to physically distance while traveling to voting stations.

In this ‘new normal’ necessitated by COVID-19, we need to also ask ourselves whether in fact international observations really made a contribution under our ‘old normal’ , or were we merely following a routine that had been institutionalised through our normative frameworks? We should also reflect on whether, in all the years of practising international observation, we did enough to strengthen the national and local structures, such as civil society, faith-based organisations, youth and traditional leaders, so that they could be able to not only be effective observers, but the first responders as mediators and facilitators in times of election related conflict? Were we operating within a paradigm that assumed that the role of international observation is more important than that played by local stakeholders?

The COVID-19 measures have placed a responsibility on all of us to ensure that the strides that various African countries had made to consolidate their democracies by holding regular, transparent, and free elections are not reversed. African civil society, governments, and regional economic organisations should seize this opportunity, and enter into a conversation that will explore the best safeguards to enable citizens to freely exercise their rights, and ensure that these rights are not negatively affected by COVID-19 measures.

Brigalia Bam, has held various key positions in South Africa, Africa, and globally. She served as the Chairperson of the Independent Electoral Commission of South Africa, and a former member of the African Union (AU) Panel of the Wise. She was the Africa Regional Secretary and Co-ordinator of the Women’s Workers’ Programme for the International Food and Allied Workers Association based in Geneva. She was also Executive Programme Secretary for the Women’s Department of the World Council of Churches. Between 1997 and 1998, as well as serving as the General Secretary of the South African Council of Churches from 1994 to 1999. She is a founding member and former President of the Women’s Development Foundation.