Africa is home to 17% of the world’s population, but only 3.8% of global COVID-19 cases. COVID-19 has spread more slowly in most of Africa than in the rest of the world, due to a number of factors. For instance, Africa has a relatively young population – more than 60% under the age of 25. COVID-19 has a higher mortality rate for older age groups, and aggravating health problems such as obesity and type 2 diabetes are less common in Africa. Also, most of Africa’s elderly population live with family rather than in old age homes.

245 days after COVID-19 was declared a pandemic in Africa, the pattern that has emerged and has been maintained is one of resilience rather than collapse and conflict @cedricdeconing @MarishaRamdeen @martinrupiya #C19ConflictMonitor

Tweet

African governments were quick to follow WHO and Africa Centres for Disease Control and Prevention (Africa CDC) guidelines, and closed their borders and introduced full or partial lockdown and social distancing measures early, when no or only very few cases had been diagnosed. Most African countries have now eased restrictions and reopened their borders for air travel, with preventative measures and testing in place. Whilst many countries across the globe are experiencing a second wave of the virus, resulting in the adoption of strict new lockdown measures, at this stage, African countries seem to be forging ahead with the gradual opening up of their economies, including allowing cross-border travel.

Apart from a few countries such as Egypt, Ethiopia, Kenya, Libya, Morocco and South Africa, COVID-19 has not yet emerged as a major public health emergency in Africa. However, for many countries on the continent, while the measures introduced to contain the virus may have mitigated the spread of the disease, the consequences of these same measures have had a significant negative impact on the livelihoods of people and the economy more generally. A sizeable portion of people in Africa depend on a daily income through informal labour or small-scale trading to support their families. Their livelihoods were significantly disrupted during the first months of the crisis, but for many the situation has now improved and life is returning to normal.

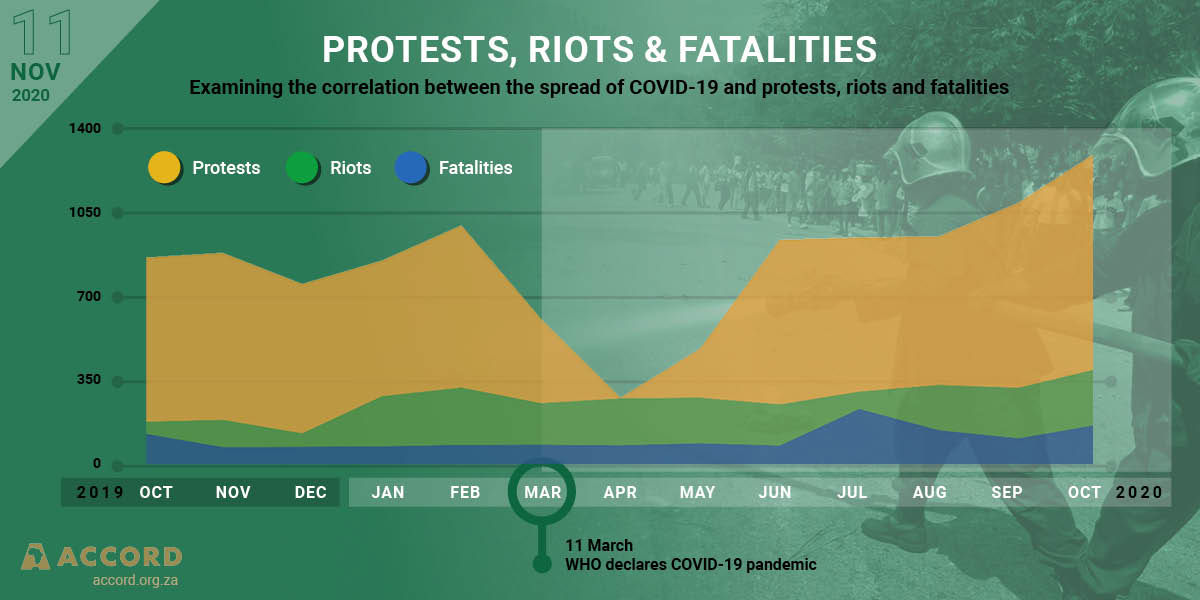

The public health emergency and related socio-economic consequences were widely anticipated to exacerbate existing vulnerabilities in societies across Africa, and to contribute to an increase in social unrest and even violent conflict. We are now eight months into the COVID-19 crisis on the continent, and these trends have not yet materialised. In fact, the lockdown measures initially resulted in a drop in most crimes and unrest, with domestic and gender-based violence being the exception. In the case of the latter, lockdown measures – including the closing of schools and work-from-home policies – have increased the risk for people who are in abusive relationships. However, the overall loss of income and disruption to livelihoods have not resulted in famine, large-scale homelessness, migration or other significant social disruptions, which implies that the resilience of African communities and governments to cope with these disruptions were significantly underestimated by those analysts who predicted chaos and collapse.

Many commentators predicted that these economic and political tensions, coupled with the public health crisis, could have resulted in much more political instability and insecurity than what has actually materialised over the past eight months. Most countries affected by armed violent conflict before COVID-19 have not experienced a significant increase (or decrease) over the last few months. There has been a gradual increase in public unrest as people voice their frustrations at COVID-19 containment measures and other political tensions since the first lockdown laws, but the number of incidents has not yet reached pre-COVID-19 highs.

Political insecurity has flared up in a few African countries amidst – but not directly linked to – the pandemic. For example, the insurgency in northern Mozambique has become much more serious during the pandemic period, and has resulted in a high number of deaths and significant displacement. The violence has forced over 300 000 people to flee their homes and to seek refuge in safer parts of Cabo Delgado, as well as in neighbouring provinces. In a worrying new trend, the violence has also started to affect towns in southern Tanzania. Twenty civilians and three Tanzanian security forces reportedly died after Kitaya was attacked by approximately 300 militants.

A human rights crisis has been unfolding in Zimbabwe since the implementation of the COVID-19 lockdown. The Zimbabwean government has been accused of persecuting those citizens who have been attempting to embark on nationwide anti-government protests against what they perceive as misgovernance. On 27 July, the Zimbabwean government announced severe COVID-19 movement restrictions, deploying soldiers in the capital, Harare, to enforce compliance and prevent the planned marches from taking place.

While the Libyan crisis continues and the opposing parties currently operate within a recent ceasefire, the WHO, which raised concerns on the rising number of cases in the last couple of months, has provided Sabha (the largest southern Libyan city) with medical supplies needed in the fight against the coronavirus pandemic. The consequence of the war has diminished capacities, which has resulted in severe shortages of testing capacity, and it is most likely that the real number of COVID-19 cases is likely to be much higher than reported. “More than half a million people require health care assistance as conflict, COVID-19 and economic collapse threaten to plunge hundreds of thousands of civilians deeper into chaos.”

The postponement of elections in Ethiopia caused tension among opposition parties, who saw this as the ruling party “exploiting the pandemic to ensure the government’s survival”. The Tigray region decided to organise its own elections, which the federal government has declared illegal – and, in response, has started to withhold finances from Tigray state. In early November, this situation escalated further when military bases were attacked, and the federal government responded with air strikes and other military actions aimed at restoring order.

In Nigeria, widespread protests continue to take place in support of a #EndSARS campaign against police abuse. Tensions escalated when security forces killed approximately 12 protesters on 20 October in Lagos. Since then, some protests have deteriorated into looting and the destruction of property. There is also the risk that the protests can act as a vector for further spreading the coronavirus.

Another worrying development was that most of the multilateral, regional and national capacities (including those in civil society) – which would otherwise have been engaged in conflict prevention, mediation, peacekeeping and peacebuilding – were also initially disrupted. Approximately one month into the crisis, most organisations started to adapt and develop new ways of working, but for several months they have been unable to do the kind of face-to-face work they were engaged in before COVID-19. However, this kind of peacebuilding work and related travel is now starting to pick up again all over Africa.

The pattern emerging out of most of Africa is one of resilience rather than conflict, due to communities and neighbours rendering support to each other; an increase in social cooperation and support provided by community organisations, women’s groups, youth organisations, faith-based organisations, the private sector and international partners; and formal relief packages in the form of social grants, tax relief, free services, etc. People, families and communities have found ways of adapting, and instead of turning to violence or other negative coping mechanisms – as many predicted – have found new ways of cooperation and mutual support in the spirit of African solidarity.

The way in which some governments, state institutions, the private sector and civil society organisations have responded to COVID-19 has built public trust and bolstered social resilience. That said, some actions have undermined trust and weakened resilience. From what we have seen over the past 30 editions of the COVID-19 Conflict & Resilience Monitor, heavy-handed enforcement of COVID-19 containment measures and countrywide lockdown measures that do not take into account local risk factors and the socio-economic needs of specific communities have damaged trust and resilience. On the other hand, measures aimed at easing the impact of the containment measures – such as free services; tax relief; economic stimulus initiatives for small, medium and micro enterprises (SMMEs); and other social protection measures – have boosted public trust and resilience. Transparency, consultation with key stakeholders (for instance, in the corporate and education sectors) and good communication have also played important roles.

On 29 July, we argued that the emerging pattern in Africa is one of resilience rather than conflict. Now, 105 days later, this pattern has been further consolidated. Apart from a few exceptions, Africa is more peaceful today than it was before COVID-19. Despite rising numbers of infections and severe economic hardships, Africa’s public health systems have not collapsed, and social order has been maintained.

Dr Cedric de Coning is a senior advisor to ACCORD and chief editor of the COVID-19 Conflict & Resilience Monitor, Marisha Ramdeen is a senior programme officer at ACCORD, and Dr Martin Rupiya is ACCORD’s innovation and training manager.