At the time of writing, Mali had registered 2 882 cases and 127 deaths, Burkina Faso 1 486 cases and 56 deaths, and Niger 1 178 cases and 69 deaths due to COVID-19. The low numbers may just be yet another reflection of the fragility of these states and the severe weaknesses of their respective health sectors. However, as no significant increase in the mortality rate is visible, it may also be the case that, for some reasons not yet adequately understood, the populations are not that prone to transmission of the virus, or they are simply less likely to develop more lethal symptoms.

The effects of COVID-19 may be mainly indirect, but the consequences could be an additional burden on political and social systems that are already close to the brink @MortenBoas @natrupesinghe

Tweet

Since 2013, the international community has been present in an unprecedented extent in the Sahel. Mali is the host to one of the largest United Nations (UN) missions in the world – the United Nations Multidimensional Integrated Stabilization Mission in Mali (MINUSMA); the European Union (EU) is present with two larger interventions, the EU Training Mission (EUTM) and EU Capacity Building Mission in the Sahel (EUCAP Sahel); France is in the country through Operation Barkhane; Sahelian states have established the Joint Force of the G5 Sahel; the European special forces’ Takuba Task Force has recently deployed; and a number of bilateral and multilateral donors have opened new programmes.

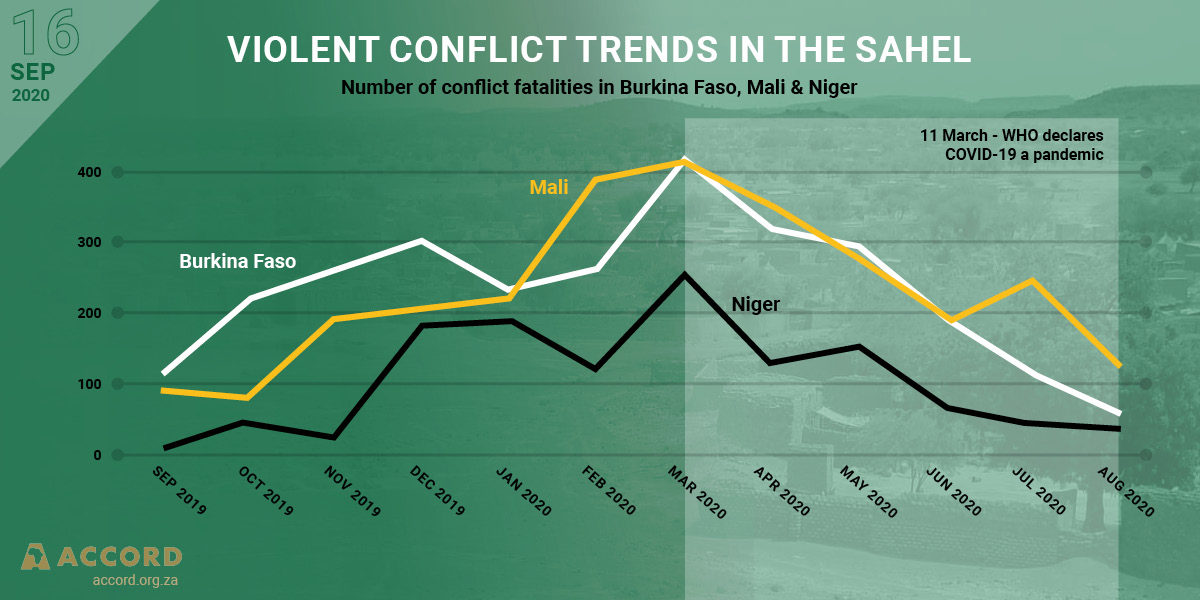

Still, the security situation is deteriorating. In Mali, jihadi insurgents are much closer to the capital area of Bamako today than they were in 2013. Burkina Faso has unravelled quickly as a combination of spill-over effects from the insurgencies in Mali, and homegrown Jihadi rebels have mounted a huge challenge to the country’s weak security sector. Niger has still partly been able to hold its ground, but the increased violence in Tillabéri – a new region no more than 60 kilometres away from the capital of Niamey – is clearly a warning signal, suggesting that state stability is not guaranteed. Added to this downward trend is the August 2020 military coup in Mali, which has led the country into another dire strait. Thus, while COVID-19 has not directly taken a huge toll, it has added yet another layer of insecurity to an already immensely precarious situation.

COVID-19 also adds another layer to the worsening humanitarian emergency: 1.2 million persons are currently displaced across the central Sahel. In Burkina Faso, this number has skyrocketed from 87 000 in 2019 to more than 1 million in 2020. Significant disruptions to education, most recently due to COVID-19, have also left children and youth in destitute and frustrating situations, sharpening the sentiments of marginalisation. Government schools – notably those administered in French – have been a clear target for jihadist insurgents, with an estimated 4 000 shut in 2020, affecting 650 000 students. During the national lockdowns, which involved the closure of schools, the pattern of attacks against schools continued, albeit at a lower rate.

It is still uncertain to what degree COVID-19 in itself will be a game-changer with regard to the violent conflict, but it is important to note that the Sahel countries will suffer indirectly from the economic recession that the pandemic causes @MortenBoas @natrupesinghe

Tweet

This is a situation that the jihadi insurgents will attempt to take advantage of. Al-Qaeda leadership has interpreted the COVID-19 pandemic as divine punishment against the infidels in the Western world, but also as a warning to Muslim countries where obscenity and moral corruption are widespread. It was claimed that the pandemic would instil fear among the Western powers, and that jihadi forces should take advantage of the weakness that this would cause and increase their attacks against them. As a reply to this, Al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM) released two audio communications in May 2020 by two of its core leaders – Abu al-Barra Ahmed and al-Hassan Rashid al-Bulaydi – calling on Muslims not to “laugh at the disease spreading in Western countries, but to remember that the infidels still impose their rule on Muslims”. Jihad was therefore the only way forward. In Burkina Faso, Mali and Niger, attacks have continued unabated during the pandemic.

While it is still uncertain to what degree COVID-19 in itself will be a game-changer with regard to the violent conflict, it is important to note that the Sahel countries will suffer indirectly from the economic recession caused by the pandemic. Not only is a likely consequence that there will be fewer resources in the international community for development purposes, but the economic downturn and disruption following the implementation of drastic measures to curb the spread of the pandemic means the loss of millions of jobs. While these jobs are not necessarily lost in the Sahel, all three Sahel countries mentioned depend on remittances from diaspora populations in Europe and elsewhere. Most of these populations work in sectors severely affected by the economic recession caused by the pandemic. While the detailed economic consequences in the Sahel are yet to be seen, it is already estimated that in some areas of Africa, remittances have dropped by 50% as the diaspora are losing jobs and income.

There is a risk that insurgent groups will continue to exploit state weakness exposed by the direct and indirect effects of COVID-19 to gain support and increase their attacks against states in the Sahel and external stakeholders @MortenBoas @natrupesinghe

Tweet

Farmers and herders in areas affected by conflict in these states have already endured significant disruptions to their livelihood activities due to heightened conflict. Price fluctuations and trade disruptions related to the pandemic have adversely affected small-scale farmers. In Mali, which is one of Africa’s top cotton producers, the plummeting price of cotton has left farmers with reduced income. In turn, this impacts on their ability to buy the fertilisers needed to cultivate crops like corn and millet. Border closures and restrictions on movement have adversely impacted nomadic pastoralist communities, which depend on mobility across borders to find pastures for their cattle. While Mali, Burkina Faso and Niger have kept livestock markets open, export flows have been reduced in Burkina Faso, and pastoralists in Niger suffered from a disruption in livestock prices and terms of trade. Competition for resources could become more acute in a context where conflicts between farmers and herders are already endemic.

A deepening of the economic crisis is to the advantage of jihadi insurgents. In Mali, particularly in the rural areas, there is already a large segment of the population who believe that the pandemic is an invention of those in power to make money – or, alternatively, a means for France and Western powers to stall Mali’s development. In areas under control of the jihadists, the government response is seen as ridiculous, and the emphasis on masks (which are not readily available) is strongly vilified in mosques, public spaces and family compounds. Jihadi rebels, such as Jama’at Nasr al-Islam wal Muslimin (JNIM) and the Islamic State in the Greater Sahara (ISGS), have both issued official statements on the pandemic, stating that Islam is a religion based on hygiene, and adherence to the Salafi scripture of the jihadi rebels will protect the population. What they are doing is taking advantage of the pandemic and the lacklustre government responses to it to encourage more community support for their struggle. Currently, there is no way of knowing the degree to which this has worked. There is, however, undoubtedly a risk that insurgent groups will continue to exploit state weakness, which has been exposed by the direct and indirect effects of the pandemic, to gain support and increase their attacks against states in the Sahel and external stakeholders.

Morten Bøås is a research professor at the Norwegian Institute of International Affairs (NUPI) and Natasja Rupesinghe is a PhD Fellow at NUPI and a DPhil candidate at the University of Oxford.