The pandemic’s second wave occurred far earlier than expected. The discovery of a variant of the virus in South Africa resulted in it spreading much faster than in the first instance and thereby also increasing the death rates at a significant pace. As a means to control the situation governments reverted to stricter lockdown measures such as closing borders and some sectors of the economy. South Africa’s lockdown was implemented during the summer holiday period in December 2020 and included the closing of borders, a ban on the trade and distribution of alcohol, a curfew and the closing of beaches. As a result of the liquor bans during both lockdowns, and with an estimated loss of over R18 billion in revenue in 2020, approximately 30 000 jobs within the industry are at stake. The rate of arrests also increased as people flouted the lockdown regulations; and approximately 7,000 people were arrested in KwaZulu-Natal alone in less than a month.

Since the end of 2020 and start of 2021, @SADC_News member states have lost ten cabinet Ministers from four countries who succumbed to #COVID-19

Tweet

Other countries in the region have faced similar situations. Zimbabwe’s Vice-President Constantino Chiwenga, announced a lockdown on 02 January 2021, which was extended until 15 February. Among the regulations was a strict curfew from 18:00 to 06:00 and the banning of informal trade for 30 days. Zimbabwe’s informal workforce comprises 85% of the country’s total number of workers, and such a regulation has further exacerbated poverty and livelihood insecurities in a country that has been affected by severe unrest in the last year.

In the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), President Felix Tshisekedi announced a curfew from 21:00 to 05:00 that came into effect from 17 December 2020. Gatherings of more than 10 people were prohibited, while holidays for schools started early. On 24 December, Botswana reintroduced a curfew from 19:00 to 04:00 until 3 January, which was further extended to 31 January 2021. The sale of alcohol was also suspended.

The sudden closure of borders resulted in a severe congestion at the Beitbridge and Lebombo borders between South Africa and Zimbabwe and Mozambique respectively, that saw both COVID and non-COVID deaths amongst people at the border. The non COVID-deaths were attributable to severe weather conditions, lack of amenities and other conditions at the border.

The pandemic has also had a negative impact on governance capacity in the region. ‘Since the end of 2020 and start of 2021, SADC member states have lost ten cabinet Ministers from four countries who succumbed to the coronavirus’. Governance incapacities also exposed the high rate of corruption. Apart from South Africa and massive corruption that took place in relation to personal protective equipment and other COVID-19 related relief, other countries on the continent have also faced similar situations. The Zimbabwean Minister of Health and Child Welfare, Obadiah Moyo, awaits trial on COVID‐related corruption charges; in Somalia, four health officials have already been jailed for misappropriating funds; and in Kenya, President Uhuru Kenyatta has been persuaded to ‘order the Ministry of Health to publish details of all contracts issued and sums paid out’.

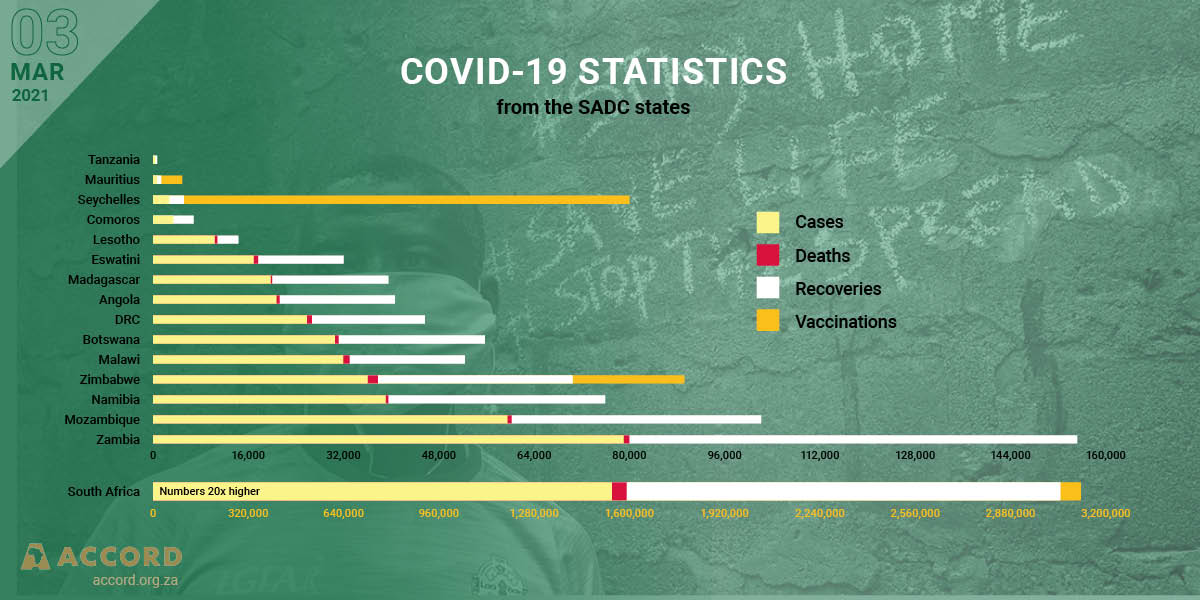

In a statement to the region, the President of Mozambique, Filipe Jacinto Nyusi, in his capacity as the Chairperson of SADC indicated that more than 50% of all new daily infections of COVID-19 on the African continent have been reported in the SADC region. His recommendation to the region included the need to ‘build on the knowledge and experience achieved in mitigating this pandemic and continue to adopt common and harmonised policies, guidelines, strategies and measures in response to the pandemic’. He recommended that the SADC committee of ministers of health establish a strong regional collaborative strategy which pools resources together to urgently acquire the vaccine for distribution to citizens setting priorities in accordance with the level of risk. According to the Africa CDC, the fatality rate for Africa has crept up from 2.1% in July last year to 2.5% currently. Ultimately 60% of Africa’s 1.3 billion people will need to be vaccinated in order to achieve continent-wide herd immunity.

Vaccination programmes and rollouts have begun in Africa and in the SADC region specifically with countries that include South Africa, Malawi, Zimbabwe and the DRC however, the pace at which the rollout is moving is cause for concern in the wake of an impending third wave, and thus becomes a race against time to immunise as many people as possible. The design and development of a vaccine developed in South Africa offers some hope to the region and continent to fast track the vaccination process, as well as bring impetus to Africa having the resources to respond to the health crisis.

Marisha Ramdeen is a Senior Programme Officer in the Peacemaking Unit at ACCORD.