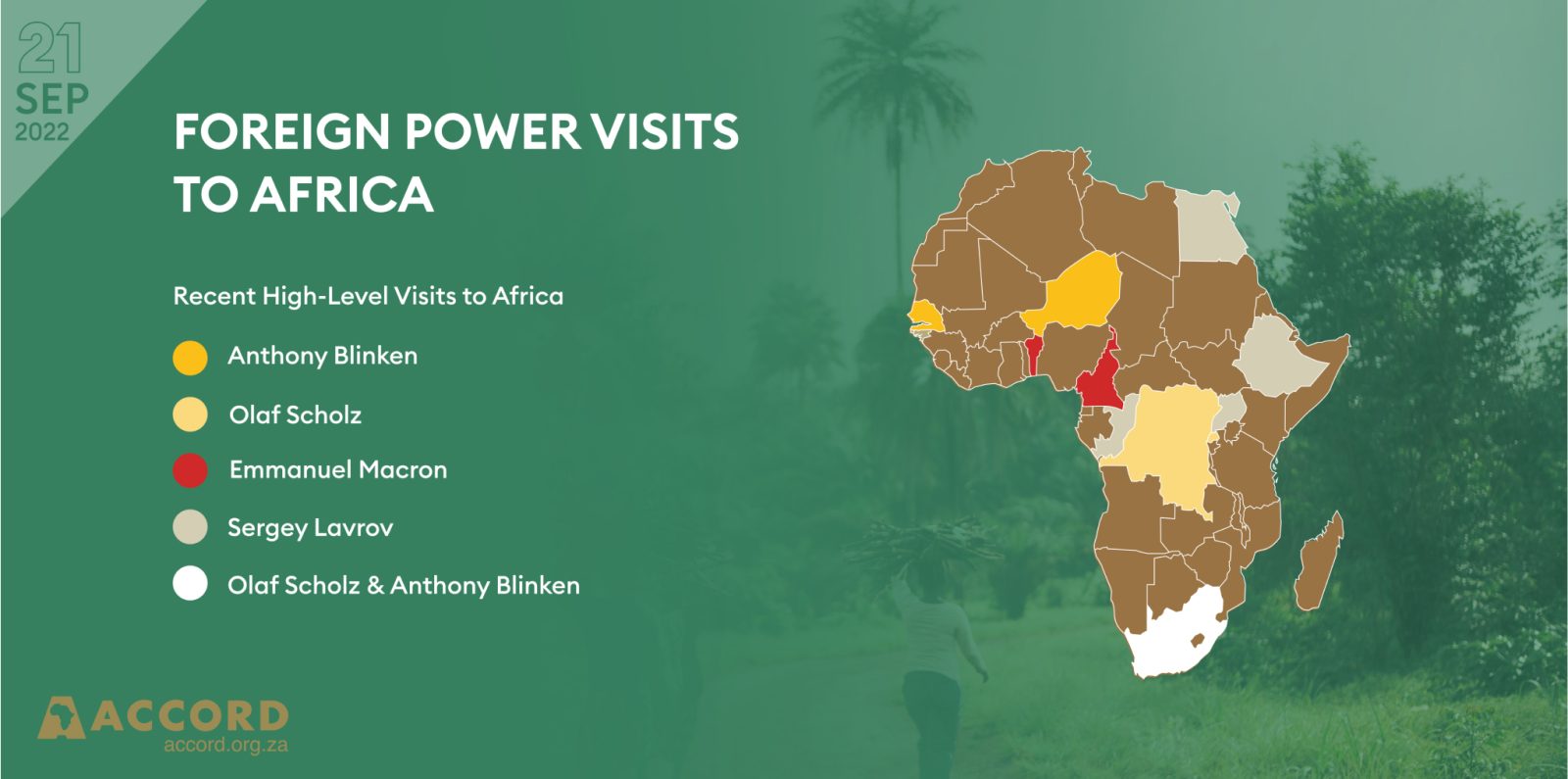

The Russian invasion of Ukraine in February heightened pre-existing global geopolitical tensions. Since June 2022, high-level visits from Germany, Russia, France, and the United States (US) to 13 African states illustrate the competition for Africa’s hearts and minds. Renewed attention by global powers has raised concerns about whether Africa can defend its interests while international relations are increasingly strained. African states must carefully consider their strategic choices and positions to prevent being drawn into global disputes.

African states must carefully consider their strategic choices and positions to prevent being drawn into global disputes.

Tweet

A New Scramble for Africa?

Africa is home to some of the world’s fastest growing economies, despite a sharp economic decrease since the COVID-19 pandemic. Many experts have identified Africa as the next big frontier – as a global economic and political force. Thus, it is unsurprising that many global powers have again turned their attention to the continent.

The visits are aimed at creating new partnerships and addressing common mutual challenges. German Chancellor Olaf Scholz’s June visit to Senegal, Niger and South Africa exemplifies some of these aims. It focused on investments, energy and food security issues, with a strong undertone of countering Russian efforts in Africa. German troops are deployed to the UN Mission in Mali. After the departure of French troops in August, Germany became the main counter to the increasing role played by Russian paramilitary groups in supporting the Malian government.

The visit of US Secretary of State, Anthony Blinken, had similar goals to those of Germany. America is attempting to patch up its foreign policy towards Africa after the decay in relations during the Trump administration. Visiting South Africa, Rwanda, and the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), Blinken used the trip to launch the Sub-Saharan Africa Strategy of the US. This strategy is a sign of American efforts to rebuild relations with the continent.

France is presented with some significant challenges in Africa, not without reason. French President Emmanuel Macron’s July tour to Cameroon, Benin and Guinea-Bissau illustrated Paris’s long-running ambition to ‘renew’ relations with Africa. This renewal process has languished, exemplified by the Malian junta’s critique of Macron’s approaches as ‘neo-colonial and patronising’.

The visits from Germany, the US, and, to some extent, France had something in common. They all are looking to counter the increasing role played by Russia and China in Africa, particularly as the conflict in Ukraine continues and tensions over Taiwan regain momentum.

Thus, Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov’s trip to Egypt, the Republic of Congo, Uganda, and Ethiopia in July is symbolic. The tour aimed to demonstrate that Russia had not been left isolated by the West’s sanctions. He presented a narrative of Russia as a respectful friend rather than an overbearing Western power with a colonial mindset. Lavrov also attempted to counter the West’s narrative on the causes of the global food crisis, blaming sanctions rather than the Russian blockade of grain exports from Ukraine in the Black Sea.

Despite these efforts, global powers still have a long way to go to rebuild trust with African countries. During his lecture at the University of Pretoria, Blinken said, ‘Washington will not dictate which choices Africa must make, and neither should anyone else.’ However, the US-Sub-Saharan Africa Strategy mentions China and Russia’s exploitation of African nations. These direct references, targeting other external forces, give the impression that the African continent is more the theatre of operations than the focus itself. And that perception is valid for the US and apparent in how other global powers have engaged with the continent.

While the fact that global powers have their strategies for Africa, when these restrict Africa’s ability to negotiate its space in the world it may diminish the continent’s agency. Some of these approaches already received some backlash. A proposed US law, the Countering Malign Russian Activities in Africa Act, seeks to punish countries that support any Russian activities that ‘undermine United States objectives and interests’. This proposed bill, yet to be discussed by the US Senate, has not gone unnoticed. The Southern African Development Community (SADC) leaders expressed dissatisfaction concerning Africa ‘being targeted for unilateral and punitive measures’ in a joint communiqué following the 42nd Heads of State SADC Summit in the DRC in August.

Credit: Laura Rubidge

Africa needs a firm stance

The intensifying competition between China and the US and powers such as the European Union (EU), United Kingdom (UK), India, Turkey, and Russia — all vying for greater influence across Africa — will likely have important consequences for peace, stability, democracy, human rights, and development across the continent.

Africa’s abundant gas and oil reserves could supplement Europe’s needs as it searches for alternatives to Russian gas, oil and coal. Despite a push for a just transition from fossil fuels, African states could still seize opportunities to negotiate favourable carbon export agreements, diversifying and strengthening their external partnerships. Senegalese President Macky Sall noted that fairer exploration and trade conditions are required if the country is to work on supplying gas to Europe.

The West should go beyond rhetorical commitments and change how it interacts with the continent. Many call Western approaches hypocritical by demanding that African states take a stance in a European conflict, while many African crises remain overlooked and under-supported.

Several African leaders have asserted their will to remain neutral during this rush of high-level visits. When Lavrov was in Uganda, President Yoweri Museveni questioned the demand that African countries should oppose particular states. He controversially said, ‘We want to make our own enemies, not fight other people’s enemies.’ In a similar vein, South African Minister of International Relations and Cooperation Naledi Pandor asserted that ‘[she] definitely will not be bullied [to choose this or else]’.

The slew of high-level visits to Africa dovetails with the continent’s importance as the largest regional voting bloc at the United Nations (UN) and a potential vital player in international politics. The ‘active non-aligned’ stance taken by many African states since the invasion of Ukraine signifies the continent’s resistance to becoming embroiled in the politics of confrontation that the powerful countries have advocated.

Nevertheless, more must be done. Indeed, African countries’ commitment to active non-alignment is not an easy task. The diversity within the continent means that unified positions are not always possible. But when individual positions are not clear, it may create challenges.

The visit of South Africa’s Defence Minister, Thandi Modise, to Moscow to attend the 10th Conference on International Security in August 2022 is a case in point. While the country has continued to communicate its neutrality and non-alignment, this visit contradicts such narratives. Rather it confirms for many in the West the view that South Africa has taken a side. Thus, governments must ensure their rationale clearly articulates their intentions when exercising their agency with external partners.

Africa has the freedom to take advantage of the various external partnerships on offer. Nevertheless, in doing so, African nations should assert their interests so that the continent benefits from renewed attention. This can help prevent African states from being used by external powers to put their interests ahead of Africa’s.

Several African leaders have asserted their will to remain neutral during this rush of high-level visits.

Tweet

Gustavo de Carvalho is a Senior Researcher on Russia-Africa ties at the South Africa Institute of International Affairs (SAIIA). He is also a Research Fellow at the Institute for Global African Affairs at the University of Johannesburg. Laura Rubidge is a Konrad Adenauer Stiftung (KAS) scholar at the South African Institute of International Affairs.