Almost a decade since the conflict in South Sudan commenced, the conflict has become further fragmented, with indiscriminate violence across the country being highly varied. Playing into these complex conflict dynamics are the impacts of climate change,which may further grievances and tensions.

Despite poor socio-economic conditions and high conflict levels, women, girls, and youth are leading and playing crucial roles in local adaptation mechanisms

Tweet

Pre-existing historical tensions within and between ethnic groups have regained relevance, primarily since the signing of the Revitalised Agreement on the Resolution of the Conflict in the Republic of South Sudan (R-ARCSS) in 2018. High levels of violence over the last few years are also a result of elites exploiting tensions between communities, which has been replicated by factional divisions between actors of the Revitalised- Transitional Government of National Unity (R-TGoNU). The R-ARCSS,and accompanying peace process, are largely viewed to have accentuated the South Sudanese civil war, facilitating a situation where elites in Juba enrich themselves from resource extraction. At the same time, the population is increasingly displaced,immiserated, and unable to rely on the state for security.

South Sudan is one of the countries in the world most affected by climate change. It is projected that by the mid-21st century, the Sahel band will include South Sudan. Adding to this challenge is a lack of sufficient funding, knowledge capacity and technical resources, weakening the government’s ability to adapt to the impacts of climate change, further increasing climate-related security risks. Consequently, to carry out its mandate to “consolidate peace and security,” the United Nations Mission in South Sudan (UNMISS), in collaboration with the R-TGoNU, must incorporate an understanding and analysis of how adverse effects of climate change interact and affect ongoing conflict and security risks while supporting community-based projects which are people-centred to address climate-related conflict drivers.

Everyday people, lives and climate change

About 11 million people, accounting for 95 per cent of South Sudan’s population, are dependent on climate-sensitive livelihoods, such as agriculture, fisheries and forestry resources. The effects of warmer and drier climates, combined with a projected average temperature increase of 0.5°C by 2030, on people’s livelihoods can increase existing vulnerabilities and tensions.

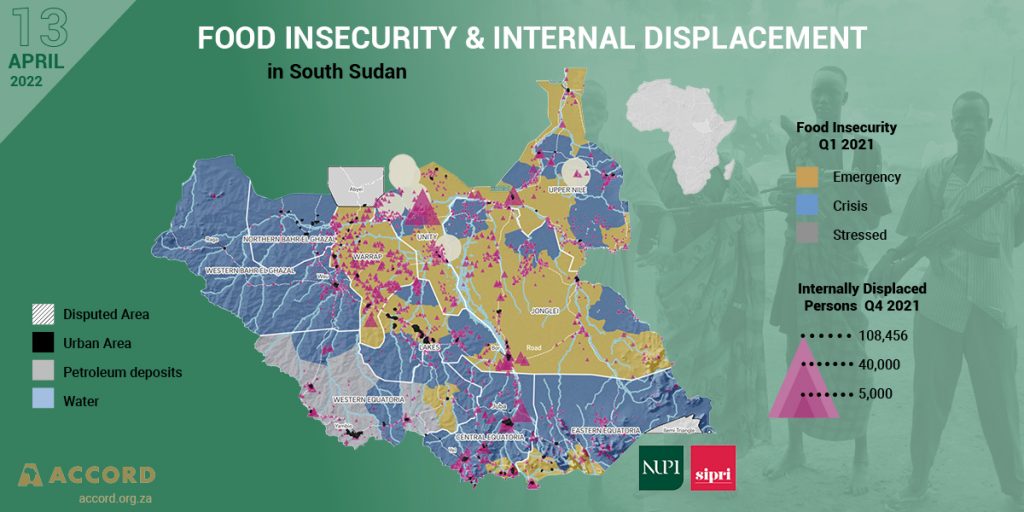

In particular, climatic changes contribute to the disruption of the migration flow, routes, and mobility in South Sudan, creating new migration patterns that impact upon the stability of both nomadic and host communities and provoke further local conflicts. For example, local authorities in the Wulu Country of Lakes State, in March 2022, reported that there had been an influx of cattle from neighbouring Rumbek East and Rumbek Central, with the commissioner of Wulu County warning that this influx would contribute to tensions between farmers, beekeepers and armed cattle keepers. Some communities have experienced upsurges in conflict and local inter-communal violence due to resource scarcity exacerbated by climate change and political challenges. This inter-communal violence further adds to displacement and tension as it continues to displace thousands of people, disrupting these communities’ fragile social fabric.

In 2021, flooding levels across 31 counties and eight states were the highest since records began. More than 835 000 people were affected by floods, leading the UN to characterise it as the worst flooding in over 60 years. Flooding in Jonglei, Eastern Lakes and Terekeka in 2020 saw herders changing their migration routes into Equatoria, adding to governance challenges and community tensions.

Since mobility is a crucial resource for many South Sudanese communities, reduced mobility due to flooding, with continued conflict, negatively affects people’s resilience. It increases food insecurity, especially since mobility is how livelihoods and coping strategies are operationalised. This affects all communities, but more so, women and girls who face structural disadvantages such as lack of land tenure, illiteracy, low social status, and high levels of child marriage. Increased food insecurity and structural disadvantages affect women and girls’ ability to respond to insecurity caused by climate change.

Some communities have experienced upsurges in conflict and local inter-communal violence due to resource scarcity exacerbated by climate change and political challenges.

Tweet

Supporting community resilience and adaptation mechanisms

Despite poor socio-economic conditions and high conflict levels, women, girls, and youth are leading and playing crucial roles in local adaptation mechanisms; these groups are resilient and are adapting to some of the impacts of climate change. In Twic East County, Jonglei State, women and youth have been at the forefront to protect the local community against flooding through building dykes, and calling for increased access to training and adult learning programmes for women to adapt to climate change. In Magawi County, women-organisations delivered aid to internally displaced persons and organised themselves to improve land rights and land administration roles.

Pastoralists’ communal resource management and herd accumulation have traditionally been effective security measures against food insecurity. These traditional adaptation mechanisms primarily rely on local traditional institutions for the management of natural resources, dispute resolution mechanisms and early warning systems. Pastoralist communities in South Sudan are also coping with the impacts of climate change by diversifying their livelihoods, and by providing education to pastoralist youth that incorporates knowledge on increasing alternative livelihood possibilities.

While these efforts show how local adaption capacity is growing, further assistance is needed to support these locally led adaptation strategies. This local knowledge and expertise should guide efforts by R-TGoNU and UNMISS to tackle climate-related security risks and to avoid doing harm with large-scale donor-driven projects. The UNMISS can learn to harness local knowledge from pastoralist communities who continue to find flexible and adaptive methods to changing climate patterns and build the capacity of traditional leaders in conflict mitigation and peace promotion. UNMISS should ensure that their climate-security analysis and efforts are gender-sensitive and sustainable beyond their programming aims and include building community capacity and supporting local adaptation strategies. Given that conflict dynamics can disrupt fragile peace processes, an integrated approach to addressing climate-related security risks can yield positive gains for development and peace processes in South Sudan. Finally, the R-TGoNU and partners should assess, map and regularly review climate-related security risks, especially as they relate to food insecurity, while paying particular attention to the needs of women, girls and female-headed households.

Dr. Andrew E. Yaw Tchie (NUPI), Anne Funnemark (NUPI) and Katongo Seyuba (SIPRI) support a collaborative project undertaken by NUPI and SIPRI to generate evidence-based information on climate related security risks for a select number of countries on the UN Security Council agenda. This article is summation of the Climate Change, Peace and Security Fact Sheet on South Sudan.