The 17 of April decision by a High Court in Malawi to temporally block the Government from instituting a 21 day lockdown in order to curb the spread of the Corona Virus (COVID-19) became one of the concrete examples of the complexities, the underlying challenges, and the dilemma facing most, if not all, African States as they put in place measures to contain the virus. This court action was brought by the Malawi Human Rights Defenders Coalition (HRDC), which argued that the Government had not sufficiently consulted with the public in order to assess the impact that the decision will have on the country’s poor and most vulnerable. The argument by the HRDC reflects the dilemma that African governments face: finding the optimal balance between the need to contain the virus by limiting direct social-contact, protecting the economy and ensuring that people’s basic needs are met.

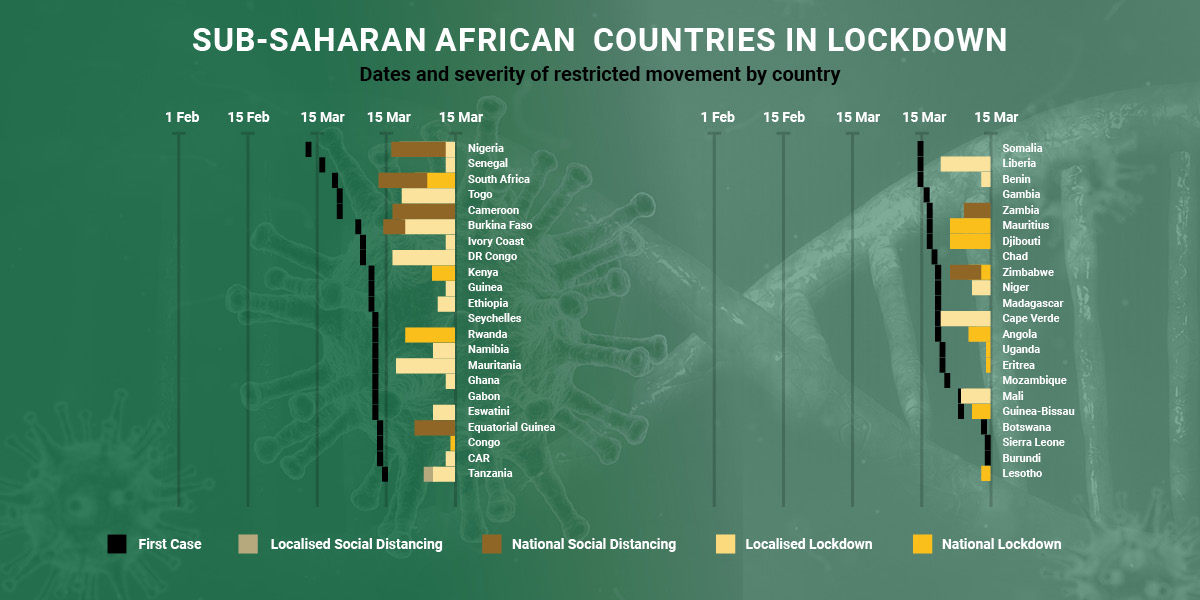

The information available paints a complex picture about the choices, the approaches, and the reasons that informed the decisions by most African countries to embark on full or partial lockdowns. For instance, there are countries such as Burundi and Lesotho, which went into lockdowns while they still had zero recorded cases, on 24 and 30 March respectively. Understandably though, both Burundi and Lesotho share borders with countries that had already instituted lockdown measures after recording COVID-19 cases. Conversely, the complexities of this dilemma were reinforced by Zambia’s decision not to institute a national lockdown citing the economic and livelihood implications for its citizens. The exception in this case was the town of Kafue which went into a lockdown that was lifted within a few days when government announced that the situation was under control.

In spite of the varying degrees of measures instituted by different African States, some trends are beginning to emerge about the effect of these lockdowns on the general public, and two deserve mentioning. First, there is strong evidence suggesting that lockdowns have a disproportionate impact on the poor and most vulnerable in our societies. With more than 85% of all workers in Africa earning a living in the informal economy, the likelihood that people can adhere to the lockdown rules beyond a few days is in doubt. This reality is linked to the second trend, namely the number of people being arrested and/or fined for lockdown related transgressions.

The question is not whether or not, but when African governments will start to relax the lockdown rules, and what kind of approaches they will adopt. For instance, among the top fifteen (15) countries with highest number of COVID-19 cases in Africa, Ghana became the first country to announce the lifting of some lockdown measures. South Africa, which stands at number two, announced a similar decision on 23 April. Both countries cited the success of their strategies to increase testing, and the need to ease the pressure on the economy, as reasons why they have opted to ease the lockdowns. Another COVID-19 related strategy adopted by most African governments was to undertake rigorous mass screening, testing and tracing programme across their countries. As of 21 April, South Africa and Ghana have conducted the highest number of tests, with 133,774 and 68,591 respectively.

Until a vaccine is developed, countries across the globe will most likely have to go through several cycles of more or less serious lockdown-type measures to contain the virus. Many African governments are now reaching the end of their first cycle. They have acted very early compared to governments in other continents, and this will have saved thousands of lives. The next step is an easing of containment measures, linked with close monitoring of infection rates through testing. If there is an increase in the number of people being infected another lockdown period will have to be imposed. This cycle may have to be repeated several times, and each time, governments, private sector, civil society and ordinary people will get better at adopting context specific approaches and coming up with better coping strategies.