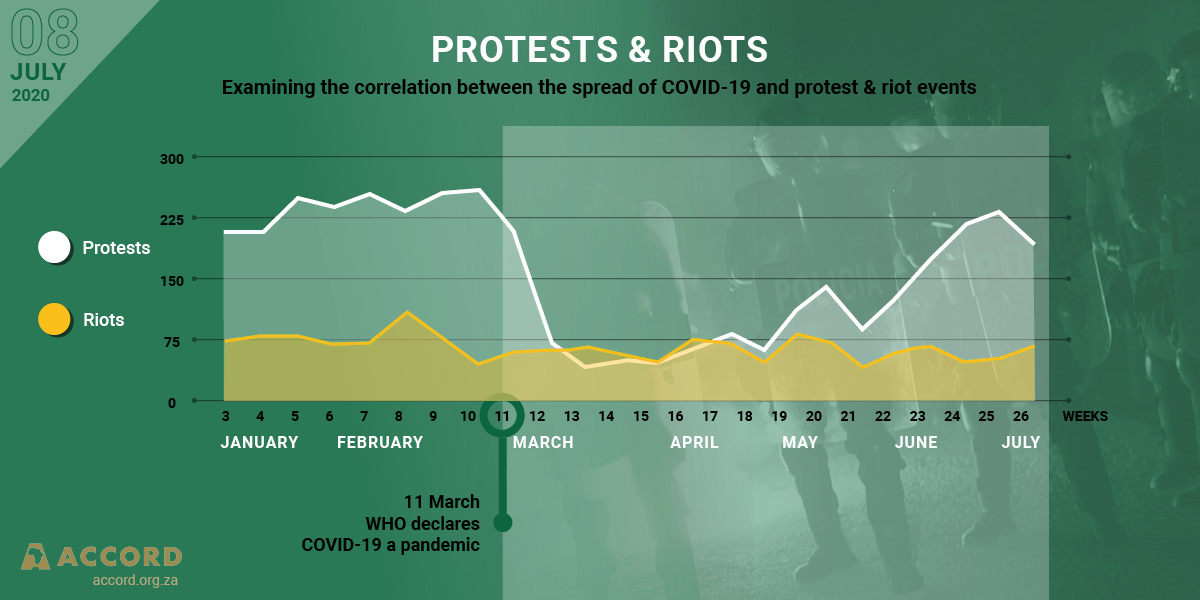

When preventive measures in the form of national lockdowns were instituted across African countries during March and April, some protest action took place in a number of countries – including Algeria, Egypt, Guinea, South Africa and Somalia – by people who were frustrated with these restrictions, as it compromised their livelihoods and civil liberties. However, overall, the number of social and political protests in Africa was significantly lower than in the months preceding the COVID-19 lockdowns. Now, approximately 100 days into the crisis, there is a notable increase in social and political protests in some countries. These protests reflect pre-existing frustrations with social and political conditions that have now been further exacerbated by COVID-19 restrictions.

COVID-19 pandemic exacerbates social and political protests in Africa.

Tweet

In the last few weeks, a rise in social and political protest action has been observed in several countries within the health sector, which reflect the growing pressure on hospitals and the vulnerability of healthcare workers. The measures taken to close and then reopen schools have created tensions within the education sector, with teachers and education authorities at loggerheads on a number of issues. Lastly, frustrations with service delivery and general political protests, including some calling for governance reforms, have increased in a number of countries.

Protests against COVID-19 restrictions

Two months into lockdown measures, Guinea was one of the first countries to exhibit violent protests against lockdown restrictions. This resulted in a high death toll when motorcycle taxi drivers clashed with security forces at a checkpoint in the western town of Friguiadi. Protests erupted in Somalia to reverse curfew restrictions that were initiated during the month of Ramadan. In Dakar, during the week of 4 June, violent protests, including clashes with security forces, erupted against a nationwide dusk-to-dawn curfew that was imposed almost three months ago to prevent the spread of the virus. This unrest in Senegal’s capital followed similar action in the holy city of Touba, where crowds of people torched an ambulance, threw rocks and looted office buildings.

Protests and strikes in the health sector

Following a spike in coronavirus cases in Nigeria, doctors in state-run hospitals suspended a week-long strike over welfare and inadequate protective equipment. Nurses from various hospitals throughout South Africa’s provinces also engaged in protests, largely for extra protection against contracting the virus. For instance, nurses at Groote Schuur Hospital in Cape Town engaged in a peaceful protest to raise awareness for their safety concerns amid the COVID-19 pandemic. Doctors treating COVID-19 patients in Sierra Leone launched a strike over unpaid bonuses, among other grievances. In Zimbabwe, 12 nurses were arrested following demonstrations over a salary dispute in Harare. The first vaccine trials against the virus on the continent began in South Africa during the week of 22 June. However, this development was met with demonstrators who expressed anti-vaccine sentiments, inciting that volunteers may not understand the risks involved in being part of the trials and were being exploited.

Protests and strikes in the education sector

In Madagascar, a large number of teachers from various private schools in Toamasina took to the streets to demand the return of their students to class. In South Africa, however, the Congress of South African Students (COSAS) union closed a school in Cape Town and called for the compulsory testing of all pupils before they return to schools. Teachers’ unions in South Africa have called on the Department of Basic Education to reconsider the decision to reopen schools, as the rate of infections is increasing in teachers and students.

Service delivery protests

Drivers of minibus taxis in Gauteng province, South Africa, went on strike – leaving thousands of commuters stranded – to demand additional financial support from the government due to the impact of COVID-19 on the public transport industry. Dozens of taxis blocked busy roads in Johannesburg and Pretoria, confronting police and soldiers. In Zimbabwe, anti-government protesters staged night protests over severe food shortages in the country since the start of the lockdown in March. Tens of thousands of garment workers in Lesotho waged a successful one-day strike during the week of 17 June for unpaid wages, returning to work after the government agreed to pay workers during the coronavirus lockdown.

Political protests

Thousands of people took to the streets of Mali’s capital city, Bamako, during the week of 19 June to demand the resignation of President Ibrahim Boubacar Keita. Demonstrators condemned the way in which the president is handling the many crises plaguing the country, such as the worsening economy, coronavirus and attacks by armed groups, together with inter-ethnic violence that has impacted negatively on thousands of lives. Political tensions also arose from a disputed legislative election in March, and allegations of corruption. In spite of security forces deployed to curb the spread of COVID-19, tens of thousands of Sudanese protested for reforms, and also demanded justice for those killed in anti-government demonstrations that ousted President Omar al-Bashir in 2019. Some protests turned violent in Ethiopia after a popular singer, Hachalu Hundessa, who was known for his political views, was murdered. Hundessa’s killing increased already existing tensions, which further increased after the government postponed the national election due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Pre-existing social and political frustrations have been exacerbated by the additional stress introduced by the outbreak of the COVID-19 crisis and the policies that were introduced to contain the virus. Initially, these policies constrained protest action – but three to four months into the COVID-19 crisis, one can observe an overall increase in social and political protest action and unrest. These protests and other mass actions will most likely further accelerate the spread of the virus, thus contributing to a vicious self-reinforcing cycle.