The COVID-19 pandemic, or more specifically the measures taken to contain the spread of the virus, is starting to have an impact on political tensions and violent conflict in Africa. Four trends are emerging: (1) some governing parties are accused of using the COVID-19 crisis to clamp down on the opposition or to silence critics; (2) some opposition parties are accused of using the crisis to unfairly criticize or discredit government actions; (3) violent conflict is continuing in spite of the virus or in some case the crisis may even be exacerbating conflict; and (4) attacks by violent extremist groups are continuing or, in some cases, may be increasing.

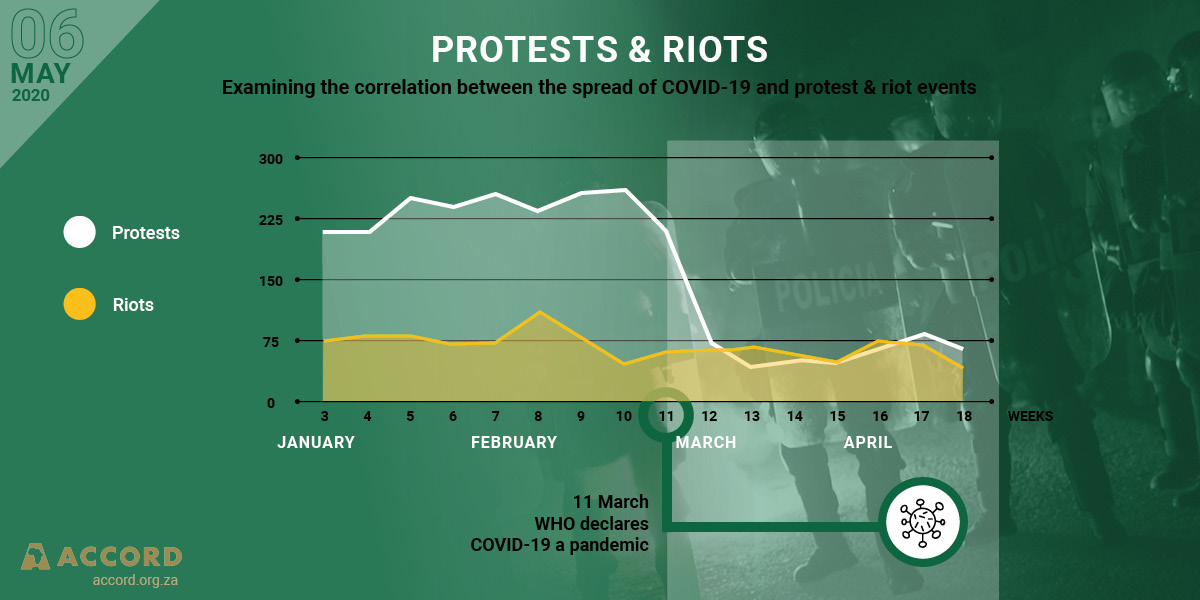

Some of the measures taken to contain COVID-19 are increasing political tensions and heightening the risk for social unrest and violent conflict.

Tweet

In several countries the parties in government have been criticized for using the COVID-19 crisis as an excuse to silence critics. There has been more that 20 incidents of verbal and physical attacks on journalists by security forces covering the COVID-19 crisis in Africa, most notably in Algeria, Madagascar, Chad, Kenya, Uganda and Zimbabwe. Some governing parties, including in Ethiopia, Malawi and Tanzania, have been accused of using COVID-19 containment measures to limit the ability of opposition parties to criticize the government, to organise or to use the crisis to postpone elections.

Opposition parties have also been accused of using the crisis to unfairly criticise governments for the actions taken to contain the virus. In Ethiopia opposition groups criticised the government for declaring a state of emergency. They argued that the state of emergency would lead to the government controlling information and silencing critics, and that it will result in human rights abuses. In the Central African Republic (CAR), civil society and opposition leaders expressed their concern over an initiative that is currently underway in the National Assembly to extend the mandate of the Head of State, Faustin Archange Touadera and to authorize the establishment of a State of emergency. In Gabon, the opposition party, criticized the government for extending its state of emergency and the lockdown in Libreville by two weeks.

In a number of countries opposition groups called for the release of political prisoners, on the premise that they are in danger of contracting the virus in prison. In Algeria, opposition parties demanded the release of ‘all prisoners of conscience.’ In Eritrea human rights groups urged the government to release political detainees held in the country’s jails that are considered to be overcrowded and unsanitary. Egyptian authorities were called upon to free political prisoners vulnerable to the coronavirus. The calls for the release of prisoners may have been informed by similar actions taken in other countries such as Morocco, Ethiopia, Malawi and Somalia, where pardons were initiated as part of the measures to curb the spread of the virus through, and in prisons.

In spite of the UN Secretary-General’s call for a global cease-fire, violent conflict continues in some countries. In Burkina Faso approximately 779,741 people fled their homes due to the recent escalation of armed conflict; in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), a number of Mayi-Mayi militia were killed in a clash with Armed Forces; and at least twelve people were killed in an attack that took place in central Mali. The war in Libya seems to have intensified and it was reported that “both sides appear to be determined to take advantage of the international focus on the pandemic and try to gain more territory(Raghavan: Washington Post, April 2020).”

In some cases, extremist groups have used the pandemic to increase their visibility. For instance, Al-Shabaab issued a statement where the group dismissed the pandemic and warned its followers that the disease was “spread by the crusader forces” who invaded the country. Africa’s al-Qaeda affiliates and Islamic State (IS) branches, as well as Boko Haram, continued its operations, including in northern Mozambique, where an IS-affiliated insurgency attacked two district capitals.

Taken together, it seems as if some of the measures and responses to the COVID-19 pandemic are increasing political tensions and heightening the risk for social unrest and violent conflict. At this stage there is no significant increase in the overall number of violent conflicts or fatalities, but a number of incidents is being reported that indicate that the risk for social unrest and violent conflict remains high.