Introduction

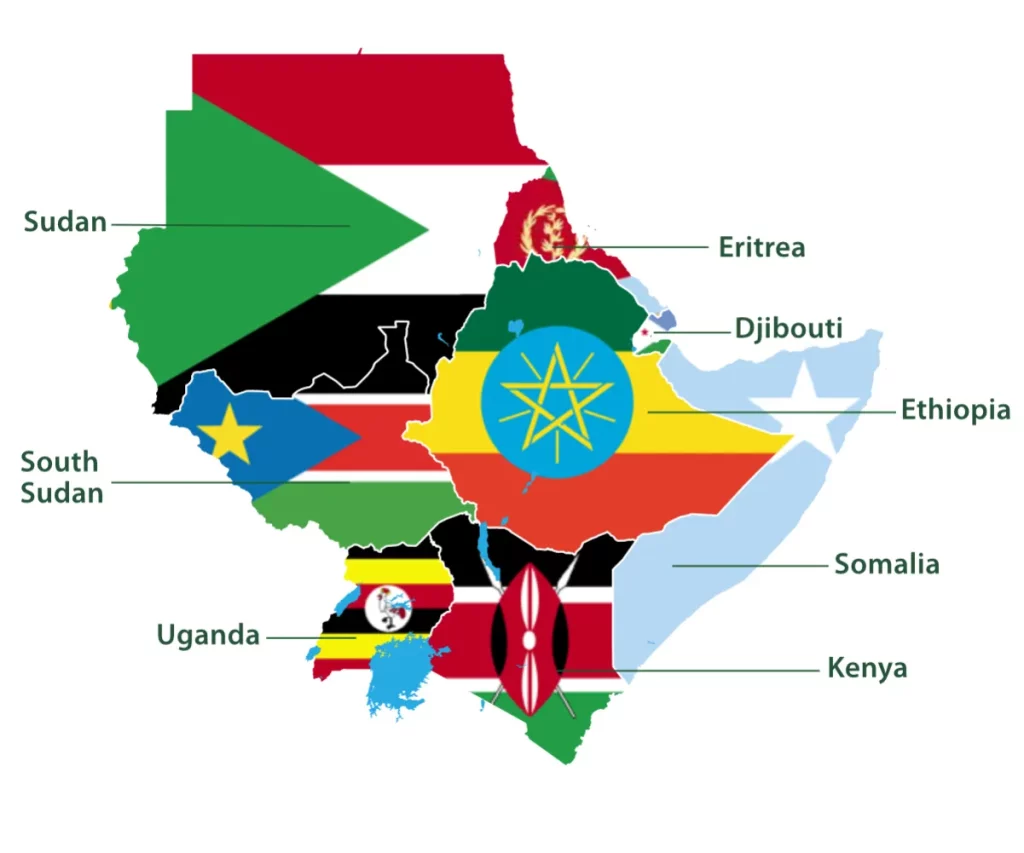

After focusing on pastoralist conflicts in three cross-border areas for ten years, the Conflict Early Warning and Response Network (CEWARN) adopted an ambitious new Strategy Framework in 2012. The strategy transformed CEWARN into a system to detect and respond timeously to the potential escalation of violent conflicts that may be triggered by economic, environmental, governance, security and social matters in all member states of the Intergovernmental Authority on Development (IGAD).1IGAD (2012) ‘CEWARN Strategy Framework 2012–2019’, Addis Ababa: IGAD

Besides expanding the thematic and geographical range, the strategy enhanced CEWARN’s partnership with civil society, which was initiated by the pioneering CEWARN Protocol in 2002.2IGAD (2002) ‘Protocol on the Establishment of a Conflict Early Warning and Response Mechanism for IGAD Member States’, Djibouti: IGAD.

This article reviews the implementation of CEWARN’s partner-ships with civil society organisations (CSOs) for data collection, analysis and response under the current Strategy Framework. It identifies outstanding challenges and lessons for (inter)governmental conflict early-warning and response systems (CEWRS).

The experiences of CEWARN and other (inter)-governmental early-warning (and response) systems show that the participation of CSOs, including local community-based organisations, expert non-governmental organisations (NGOs) and research institutions, can prove beneficial at all stages of the early-warning and response process, including data collection, analysis, warning and the implementation of responsive action. Civil society reporters may collect data on local-level dynamics that cannot be captured through media monitoring, highlight human security concerns, and assist in the verification and evaluation of incident reports.3

Catherine Barnes (2009) ‘Civil Society and Peacebuilding: Mapping Functions in Working for Peace’, The International Spectator 44(1), 131–47; Paul Goldsmith (2020) ‘Introduction: What Is CEWARN?’, in Paul Goldsmith (ed.), Conflict Early Warning in the Horn: CEWARN’s Journey, Djibouti: IGAD, pp. 8–17; Amandine Gnanguênon (2018) ‘Afrique de l’Ouest : faire de la prévention des conflits la règle et non l’exception’ Bruxelles: l’observatoire Boutros-Ghali, 2018, 12; Chukwuemeka Eze and Osei Frimpong Baffour (2021) ‘Contributions of Early Warning to the African Peace & Security Architecture: The Experience of the West Africa Network for Peacebuilding (WANEP)’, in Terence McNamee and Monde Muyangwa (eds), The State of Peacebuilding in Africa: Lessons Learned for Policymakers and Practitioners, Cham: Springer International Publishing, p. 182. Research institutions may enrich analyses by adding alternative perspectives to those of (inter)-governmental officials and proposing complementary responses.4Jakkie Cilliers (2005) ‘Towards a Continental Early Warning System for Africa’, Pretoria: Institute for Security Studies, p. 7; Heinz Krummenacher et al. (2001) ‘Practical Challenges in Predicting Violent Conflict: FAST: An Example of a Comprehensive Early-Warning Methodology’, Bern: Swisspeace, p. 4. In local-level responses, community leaders and CSOs may warn local stakeholders, undertake rapid preventive interventions, and facilitate dialogue among community members.5WANEP (2019) ‘Practice Guide on CSOs Engagement with Intergovernmental Organizations’, Accra: WANEP. Goldsmith (2020) pp. 8–17, op. cit. In high-level crisis responses, specialist conflict resolution NGOs may provide technical support to mediators. In long-term preventive measures, non-governmental experts may assist in policy development to tackle countries’ structural vulnerabilities.6Michael Aeby (2021) ‘Civil Society Participation in Peacemaking and Mediation Support in the APSA: Insights on the AU, ECOWAS and SADC’, Cape Town: Institute for Justice and Reconciliation, pp. 1–7. Participation is hoped to augment the legitimacy and acceptance of conflict interventions of intergovernmental organisations (IGOs).7Michael Aeby and Jamie Pring (2021) ‘The Buzz about Inclusion in Peace Research, Policy and Practice in IGAD and SADC’, in Ulf Engel et al. (eds), APSA Inside-Out: Researching the Inner Life of the African Peace & Security Architecture, Leiden: Brill Publishers, p. 186; Helena Puig Larraui (2013) ‘New Technologies and Conflict Prevention in Sudan and South Sudan’, in Francesco Mancini (ed.), New Technology and the Prevention of Violence and Conflict, New York: International Peace Institute, p. 85. To reap these benefits, governments and CSOs must navigate organisational, technical and political challenges.8Interview with Camlus Omogo, 8.06.2023, Addis Ababa.

Besides IGAD, the African Union (AU) and six Regional Economic Communities (RECs) have established early-warning (and response) systems or relevant capabilities.9Interview with Respondent 11, 27.9.2021, online; Ulf Engel (2018) ‘Early Warning and Conflict Prevention’, in Matthias Middell (ed.), The Routledge Handbook of Transregional Studies, Abingdon: Routledge, p. 578; UN (2018) ‘Mapping Study of the Conflict Prevention Capabilities of African Regional Economic Communities’, New York: United Nations. These systems differ in their design and priorities. However, several utilise technology that was created for the CEWARN Reporter, feature national centres analogous to CEWARN, and work with CSOs for data collection, analyses and responses. CEWARN’s 20 years of experience in partnering with civil society, therefore, holds lessons for CEWRS that grapple with similar challenges.10Doug Bond (2020) ‘Constructing the CEWARN Model’, in Paul Goldsmith (ed.), Conflict Early Warning in the Horn: CEWARN’s Journey, Djibouti: IGAD, pp. 90–96; Interviews with Alimou Diallo, 21.09.2021, online; Habib Kambanga, 06.10 2021, online; Ifeanyii Okechukwu, 13.09 2021, Accra; Respondent 11, Respondent 28, 3.07.2023, online.

This article reviews the implementation of CEWARN’s civil society partnerships under the Strategy Framework to identify challenges and draw lessons for (inter)governmental CEWRS and CSOs. To this end, it examines how CSOs contributed to the collection of early-warning data, analyses, and responses since the adoption of the Strategy Framework. The study is based on 20 key information interviews with IGAD and CSO representatives.11The research benefited from funding from the Swiss National Science Foundation.

The study shows that the Strategy Framework enables civil society participation at all stages of the warning-response process, but the modalities of its implementation bear technical, operational and political challenges that require continuous experimentation. The findings show that:

- Expanding the net of community monitors who reported local-level incidents in the original cross-border clusters across all IGAD countries was unfeasible. Therefore, CEWARN built networks of NGO reporters, whose primary role is to verify and evaluate data that is collected through media monitoring.

- The integration of 45 National Research Institutes (NRI) with sectoral specialisations in seven nations enhanced CEWARN’s analytical capacity. But producing periodic countrywide sectoral analyses remains challenging for scarcely resourced institutes. Crucially, the sensitivity of sharing security-related information complicates research partnerships.

- The multi-agency model of CEWARN’s Conflict Early Warning and Response Units (CEWERU), in principle, ensures the coordination of government and CSOs in planning and implementing preventive action. The model, however, hinges on the full operationalisation of CEWERU Committees by states.

- Consolidating a funding model for NGOs and NRIs to mobilise third-party funding to contribute to CEWARN is the crux to sustaining the envisaged partnerships.

- Continuously building confidence between government and civil society, and maintaining sufficient civic space for CSOs to undertake early warning and response activities are essential to implement the Strategy Framework and envisaged partnerships.12Interviews with Omogo; Respondent 12, 5.11.2021, online; Respondent 14, 20.10.2.21, online; Respondent 25, 06.2023, online; Respondent 29, 14.06.2023, Addis Ababa.

CEWARN’s original cross-border clusters and evolving architecture

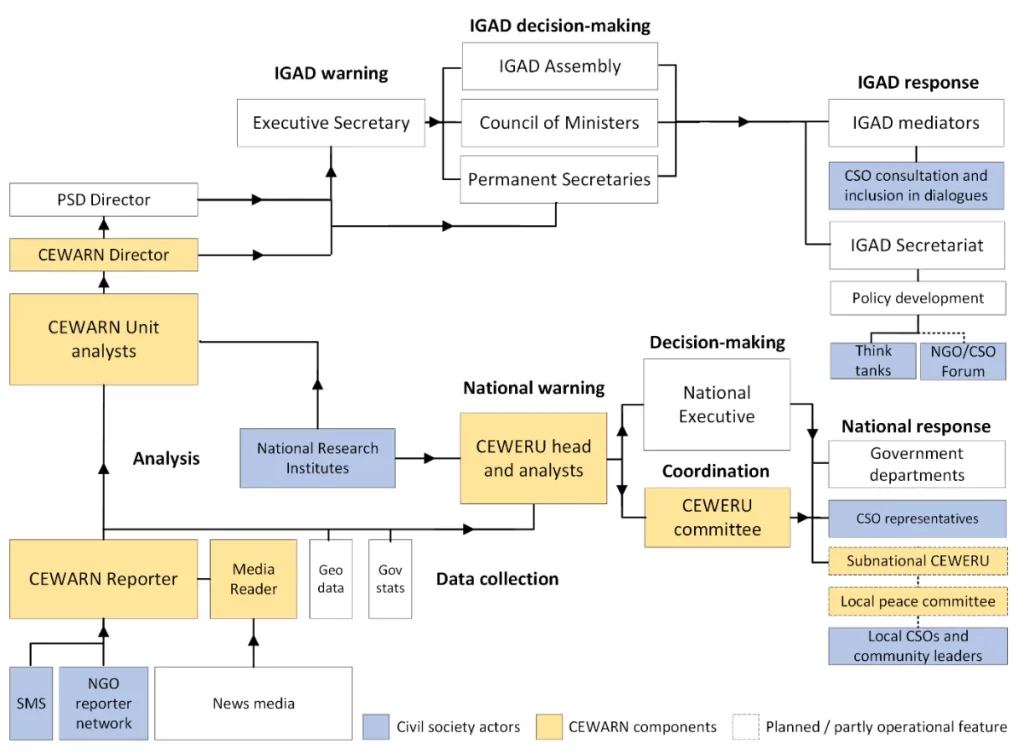

CEWARN was designed as a decentralised system to enable early warning and responses by IGAD states on the national and local level. The CEWARN Unit in Addis Ababa is the linchpin of the system that became operational in 2003. It coordinates data collection, analyses, information-sharing, and joint responses between governments. CEWERUs that are embedded in ministries oversee all operations in countries and orchestrate responses.13Goldsmith (2020) pp. 8–17 op. cit.; Respondent 12.

For ten years, CEWARN focused on pastoralist conflicts in three border areas between Ethiopia and her neighbours, Djibouti, Somalia, Kenya, Uganda and South Sudan.14Ibid. Whereas borderlands are sensitive to national security, the rationale for initiating CEWARN in the Dikhil, Karamoja and Somali cross-border clusters was to address conflicts that required cooperation between governments and gain their confidence in CEWARN.15Respondent 25. Intrastate conflicts, meanwhile, fell outside CEWARN’s mandate. To prevent pastoralist conflicts, CEWARN established a network of field monitors and peace committees in the clusters.16Goldsmith (2020) 8–17, op. cit.; Respondent 12.

The contributions of CSOs to CEWARN’s operationalisation and original clusters are well-documented.17Cirû Mwaûra and Susanne Schmeidl (eds) (2002) Early Warning and Conflict Management in the Horn of Africa, Lawrenceville: Red Sea Press; Goldsmith (2020) op. cit. While international NGOs were instrumental in designing CEWARN, a commercial software developer, Virtual Research Associates, created the CEWARN Reporter.18Bond (2020) p. 91, op. cit.; Respondent 12. Incident and situation reports, which individual community-based monitors entered into the CEWARN Reporter, constituted the primary data collection method and permitted CEWARN to develop predictive capability for violent incidents, such as cattle raids.19Bond (2020) p. 92, op. cit.; A. K. Kaiza (2020) ‘Mapping Conflict: Using Data and Information to Promote Peace’, in Paul Goldsmith (ed.), Conflict Early Warning in the Horn: CEWARN’s Journey, Djibouti: IGAD, p. 81. To prevent incidents, CEWERUs alerted community leaders and law enforcement to intervene. Civil society actors were represented in local peace committees that effected preventive measures.20Goldsmith (2020) pp. 8–17, op. cit.; Respondent 12. CEWARN’s Rapid Response Fund served to finance interventions and prevention initiatives.21Girma Kebede (2020) ‘Funding Peace: The Rapid Response Fund’, in Paul Goldsmith (ed.), Conflict Early Warning in the Horn: CEWARN’s Journey, Djibouti: IGAD CEWARN, pp. 8–17.

Studies on CEWARN clusters highlighted several challenges, including poor communication infra-structure in remote areas and biased reporting, training deficits, and information overload among community monitors.22Bond (2020) p. 92, op. cit.; Kaiza (2020) pp. 18, 81. Analyses of CEWARN in Kenya and South Sudan mentioned distrust among community members and local officials’ vis-à-vis monitors.23Godfrey Musila (2013) ‘Early Warning and the Role of New Technologies in Kenya’, in New Technology and the Prevention of Violence and Conflict, Francesco Mancini (ed.), New York: International Peace Institute, p. 55; Larraui (2013) p. 87. CEWARN’s decentralised design was lauded for fostering democratic security governance by including CSOs in CEWERU Committees.24Cara Marie Wagner (2013) ‘Reconsidering Peace in the Horn of Africa’, African Security Review 22(2), 47. The operationalisation was, however, protracted, with one study finding that by 2013, three countries had functional CEWERUs.25Kasaija (2013) p. 12 op. cit. Establishing CEWERUs proved time-consuming as their capabilities and location within ministries had to be negotiated. State officials were hesitant vis-à-vis the intergovernmental information-gathering system and involvement of non-state actors.26Interviews with Tamrat Kebede, 16.06.2023, Addis Ababa; Tamiru Lega, 15.06.2023, Addis Ababa; Respondent 30, 20.06.2023, Addis Ababa; Respondents 25 and 29. Since the CEWARN Protocol did not make inclusive CEWERU Committees compulsory, some governments solely appointed CEWERU heads.27Omogo. Several studies pointed to CSOs’ dissatisfaction with the lack of access to collated CEWARN data and absence of their concerns in published CEWARN reports.28Musila (2013) p. 55 op. cit.; Larraui (2013) pp. 85–87; LPI (2014) ‘Civil Society and Regional Peacebuilding in the Horn of Africa: A Review of Present Engagement and Future Opportunities’, Addis Ababa: Life & Peace Institute, p. 25.

The strategy change of 2012 would transform CEWARN into a system to monitor conflict factors relating to economic, environmental, governance, social and security across the territories of all IGAD countries. The thematic expansion shifted the focus from rapid local responses to early warning and policy development on the IGAD and national level. Whereas the CEWARN Unit and CEWERUs remain the cornerstones, the infrastructure of cross-border clusters was merged into national architectures.CEWARN also adopted new data collection methods that are explained in Figure 1.29Interviews with Omogo, Respondents 14 and 29.

Policy framework

Civil society participation in CEWARN is envisaged in IGAD policies but the modalities are within governments’ discretion. The Agreement establishing the IGAD encourages collaboration with non-governmental agencies in pursuit of IGAD’s objectives which include promoting peace.30IGAD (1996) ‘Agreement Establishing the Inter-Governmental Authority on Development’, Nairobi; IGAD, Art 18. The CEWARN Protocol provides that national CEWERU Committees comprise representatives of the government, parliament, police, military and non-state actors including NGOs, religious organisations and research institutions. Governments shall promote the involvement of NGOs, academics and community groups in data collection. CEWERUs should conduct analyses with research institutes that are represented in Committees and with independent academic institutions. Analyses should be available to the CEWARN Unit and “to the greatest extent possible” to civil society, but states may restrict access to information on grounds of national security. To effect early responses, governments may involve CSOs in alerting wider society and resolving grassroots conflict.31IGAD (2002) Art 11–12, Part II-IV, op. cit.

By expanding the thematic and geographic scope to prevent conflicts across IGAD countries, the Strategy Framework modified the role of civil society reporters, research institutes and responders. It underscores the mobilisation of government and civil society as CEWARN’s key strength but acknowledges a lack of analytical, communication and implementation capabilities among national actors. The strategy aspires to build relevant capabilities in CEWERU Committees and involve citizens and private enterprises to promote ownership and human security.32IGAD (2012) pp. 24, 33, 61, op. cit.; Respondent 12.

At its introduction, scholars greeted the ambitious strategy with scepticism, owing to the scarcity of resources and governments’ reluctance to accept warnings and address conflicts within their jurisdiction.33Phillip Apuuli Kasaija (2013) ‘The Intergovernmental Authority on Development’s Conflict Early Warning and Response Mechanism’, African Security Review 22(2), 11–25; Rania Hassan (2013) ‘CEWARN’s New Strategy Framework’, African Security Review 22(2), 26–38. The strategy not only exceeded the Protocol in terms of the thematic breadth and CEWARN’s policy development function, but posed political challenges by tasking CEWARN to address governance-related vulnerabilities.34Omogo. Since the Protocol was not amended, the modalities of participation in CEWERUs remain at the discretion of governments.35Interviews with Omogo; Respondents 25 and 29.

IGAD’s Regional Strategy likewise aims to involve CSOs in conflict prevention and in promoting good governance, democracy and human rights.36IGAD (2016) IGAD Regional Strategy: The Framework (2016-2020), Djibouti: IGAD, p. 9.

The Regional Gender Strategy identifies CSOs and CEWARN as key implementing agencies to foster women’s participation in prevention and peacemaking.37IGAD (2015) ‘IGAD Gender Strategy and Implementation Plan 2016–2020’, Djibouti: IGAD, p. 45. A draft Protocol on Preventive Diplomacy and Mediation, which is not yet in effect, promotes civil society inclusion in mediations and foresees that CEWARN systematically supports IGAD peace diplomacy through analyses.38IGAD (2019) ‘Draft Protocol on Preventive Diplomacy and Mediation’, Nairobi: IGAD, Art 5, 14; Interview with Respondent 18, 16.06 2023, Addis Ababa. In sum, IGAD policies envisage civil society contributions at all stages of the warning-response process but let governments decide on the extent to which CSOs may participate.

Data collection

The implementation of the Strategy Framework began in 2013 but data collection on the five analytic domains started in 2016. The strategy made it necessary to expand data collection methods and external partnerships.39Respondent 12. Besides government statistics for structural vulnerability analyses, CEWARN planned to leverage geospatial data and enable crowdsourcing by permitting observers to report incidents via SMS.40IGAD (2020) ‘Conflict Early Warning and Response Mechanism (CEWARN) Brochure’, Addis Ababa; IGAD. Automated media monitoring became a central data collection instrument, while the benefits of collecting information on a spectrum of issues across countries through a resource-intensive reporter network were weighed against the cost.41Respondent 14.

Rather than solely relying on media sources, CEWARN decided to modify the algorithm and questionnaire of the CEWARN Reporter and to develop nationwide networks with a maximum of 60 reporters per country. In lieu of relying on individual community-based field monitors as in the initial clusters, CEWARN partnered with established NGOs and academic institutions to recruit and train reporters.42Respondents 12 and 14.

CEWARN retained and modified the reporter system for several reasons. Firstly, since “CEWARN is about democratising security,” IGAD committed to partnering with NGOs to foster public ownership of the system and ensure that it did not duplicate state intelligence. Secondly, expanding the net of field monitors, whose reach was limited to their immediate surroundings, to cover entire national territories was impractical. Therefore, CEWARN partnered with NGO officers and academics who could draw from their respective networks of informers, brought relevant knowledge on a wider geographical area, and were better equipped to assess the relevance of information. The better-qualified reporters were not only hoped to improve reporting but to balance out biases in media-based data.43Omogo, Respondents 25 and 29. Thirdly, as the monitoring network in the clusters cost US$ 0.6 million per annum, augmenting the number of community monitors to cover all IGAD countries was financially unsustainable. NGOs, in contrast, were expected to raise donor funding independently and were compensated minimally for their contribution to CEWARN.44Respondents 12 and 14. Fourthly, whereas community members were more willing to share information with civil society than government actors, CEWARN abandoned the original model as it could not guarantee the safety of local monitors, who had been accused of “selling out” and targeted by violence-makers in their communities.45Omogo, Respondent 30.

NGOs were selected owing to their ability to cover analytic domains and vetted in coordination with governments.46Respondent 12. While CEWARN set technical standards, governments’ approval for the selection was indispensable to maintain trust in CEWARN data and analyses. The negotiated selection implied a bias against outspoken NGOs and compromises regarding NGOs’ capabilities.47Omogo; Respondents 14, 25 and 29. Civil society representatives raised concerns that the rigorous selection encourages self-censorship among reporters, as does the strict legislative regulation of civic activities in IGAD countries.48Kebede, Lega, interview; Respondents 14, 25 and 30.

By 2021, CEWARN featured networks with up to 60 trained NGO reporters in seven IGAD countries and continuously gathered information in all analytic domains through the CEWARN Reporter. Since NGOs were concentrated in urban centres, the network was thin in rural areas, and the NGO reporters could not complement the media monitoring data with information on local-level dynamics on a meaningful scale.49Omogo, interview; Respondents 14 and 29. The quality of the initially promising data gradually deteriorated as fatigued reporters entered inaccurate information. The envisaged model eventually proved unsustainable owing to a “mismatch of expectations.” Whereas CEWARN offered training and equipment, NGOs expected to be fully compensated for reporting tasks rather than raise third-party funding to provide their services. CEWARN, meanwhile, could not acquire the required funds centrally.50Omogo.

Rather than abandoning civil society reporters, who were integral to the system from the onset, CEWARN is presently testing readjustments to the reporter model. Instead of complementing the wealth of information from media monitoring with reports on local-level incidents, the primary function of NGO reporters now consists of verifying, evaluating and contextualising media-based findings.51Omogo.

Early-warning analysis

CEWARN analyses are based on the above-described data sources and conducted by country experts at the CEWARN Unit and analysts in CEWERUs, who are responsible for verification, triangulation and analysis.52Respondent 12. Country-specific information is only accessible to data managers, national analysts, the CEWARN directorate and CEWERU. The CEWARN Unit does include NGO-seconded analysts, but non-state actors contribute to analyses through NRIs and, in rare instances, CEWERU Committees.53Respondent 14, 29 and 30.

While the CEWARN Protocol envisaged one NRI per country, the new strategy increased the number to five research institutes that specialise in an analytical domain bringing the total to 45. The NRIs comprise government-approved universities and think tanks that were chosen owing to their sectoral expertise with the intent to tap into their ongoing work. NRIs issue quarterly situation reports on developments in their thematic domain to the CEWARN Unit and CEWERU.54Kebede; Omogo; Respondents 12 and 25.

The expansion to 45 specialist NRIs has enhanced CEWARN’s analytical capacity. NRI reports are, according to CEWARN’s Director, valued by CEWERUs whose Committees include the NRIs to develop response options.55Omogo. Challenges in implementing the research partnership, firstly, result from the limited capacity of scarcely resourced institutes to conduct country-wide sectoral analyses periodically.56Kebede; Respondents 14 and 29. Secondly, whereas CEWARN compensated NRIs in the past, their contributions are now expected to be financed by member states or donors.57Kebede; Omogo. Thirdly, although CEWERUs should grant NRIs selective access to CEWARN data,58Omogo; Respondent 29. data-sharing with the non-state entities remains tightly controlled owing to the sensitivity of security-related information.59Kebede; Lega; Respondent 30 and 25 Fourthly, since academic freedom is limited and fluctuates in IGAD countries, researchers must exercise caution when analysing governance-related conflict vulnerabilities. Finally, the system would require a continuous feedback mechanism to ensure NRI analyses are adequate for decision- and policymaking.60Respondent 14, Respondent 30.

In Kenya, whose peace infrastructure had inspired CEWARN, CSOs other than NRIs could contribute to analyses and drive the agenda of the CEWERU Committee.61Interviews with Omogo, Respondents 12 and 14, Respondent 15, 21.10.2.21, online. This was, however, not feasible in CEWERUs of governments that deemed sharing security-relevant information for analyses too sensitive.62Kebede; Lega; Respondents 30 and 25.

Warning and response

Prior to CEWARN’s reform, the response component was the outstanding feature of the decentralised system and the main activity in cross-border clusters. Besides prompting rapid interventions by police and community leaders to mitigate violence, CEWARN developed and accompanied the implementation of prevention policies including a cross-border trade regime and livestock markets to prevent cattle rustling.63Omogo; Respondent 25 and 30.

The new strategy shifted CEWARN’s focus from local-level responses to early-warning capabilities and policy-development on the national and IGAD level. When aiming to recommend responses to tackle vulnerabilities relating to economic, environmental, governance, social and security matters, CEWARN “bit more than we can chew” given the breadth of response options and responders. Whereas CEWARN now primarily functions as an early-warning system, it is reinvigorating its response component and strengthening its policy-development capabilities for structural conflict prevention.64Respondent 29.

CEWARN enables government responses and does not take independent action, but the CEWARN Unit informs IGAD decision-makers, who may prompt IGAD responses, including preventive diplomacy, mediation and policy-development in the IGAD Secretariat. Early-warning reports are evaluated by the CEWARN Director and, if required, submitted to the Peace and Security Division Director and IGAD Executive Secretary. The latter may decide to inform states’ Permanent Secretaries, the Council of Ministers and Assembly of Heads of State and Government.65Respondents 18 and 25.

CEWRS commonly grapple with a warning-response gap that is often attributed to the difficulty of communicating early-warning information and a lack of political will by decision-makers to take costly preventive action.66Christoph Meyer, Chiara de Franco, and Florian Otto (2019) Warning about War: Conflict, Persuasion and Foreign Policy. Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, p. 5. In CEWARN’s decentralised system, the gap relates to the fact that states are responsible for responses.67Respondents 14, 25 and 29. Communicating warnings to inform policy-making by governments is particularly challenging and a focal point of CEWARN’s communication strategy with Permanent Secretaries.68Omogo. Within IGAD, the gap may be narrowed by streamlining standard operating procedures for the communication of warnings to avoid bottlenecks and ensure politically inconvenient warnings are passed on.69Respondents 14, 25 and 29.

In IGAD, early-warning and mediation support are not formally integrated as no standard procedures exist to leverage CEWARN’s analytical capacity to plan mediations by Special Envoys. In practice, CEWARN produces analyses to support mediations when the need arises. CEWARN staff who are seconded to Special Envoys’ offices provide informal links between the early-warning and mediation structures, which are coordinated in meetings of the Peace and Security Department.70Interviews with Omogo; Respondent 23, 18.10.2021, online; Respondent 25.

IGAD’s peace diplomacy provides few opportunities for civil society participation. The Mediation Support Unit (MSU) partners with NGOs for knowledge management and the mediation roster features civil society actors, but these structures are not used for mediations.71Interviews with Ahmed Hersi, Interview, 3.2.2022, online; Omogo, Respondent 18 and Respondent 27, 18.06.2023, online. IGAD-mediated dialogues to negotiate the original and Revitalised Agreement to Resolve the Conflict in South Sudan featured civil society delegations.72Interview with Stephen Oola, 10.03.2022, online, Respondent 17, 13.03.2022, online; Jamie Pring (2017) ‘Including or Excluding Civil Society? The Role of the Mediation Mandate for South Sudan (2013–2015) and Zimbabwe (2008–2009)’, African Security 10(3–4), 223–38. Inclusion mechanisms, however, had little bearing on negotiation outcomes that were determined in closed meetings between leaders of conflict parties and IGAD states.73Michael Aeby (2022) ‘How African Organisations Support Peace Agreement Implementation’, Global Transitions Series, PeaceRep: Edinburgh, pp. 37–50; David Deng (2018) ‘Compound Fractures: Political Formations, Armed Groups and Regional Mediation in South Sudan’, East Africa Report, Pretoria: Institute for Security Studies, p. 6; ICG (2019) ‘Salvaging South Sudan’s Fragile Peace Deal’, Africa Report 270, Brussels: International Conflict Group, p. 8.

CEWRS may prompt both crisis interventions and long-term prevention.74David Nyheim (2015) ‘Early Warning and Response to Violent Conflict: Time for a Rethink?’ Saferworld: London, p. 6. CEWARN seeks to shift the modus operandi from issuing “fire alerts” to forecasting long-term trends to address structural vulnerabilities through policymaking.75Respondents 14, 25 and 29. The CEWARN Unit, therefore, conducts national and regional conflict profiling and scenario building, flags conflict drivers such as taxation to governments, and explores policy options.76Omogo; Respondent 14, Kebede; Lega; Respondent 30, interview, 21.06.2021, online. While sensitive country analyses are confidential, CEWARN publishes regional reports that warn against conflict drivers including electoral mismanagement in general terms.77IGAD (2021) ‘CEWARN Regional Conflict Profiling 2021’ (Addis Ababa: Intergovernmental Authority for Development, Addis Ababa: IGAD, p. 7; IGAD (2022) ‘CEWARN Quarterly Early Warning Report’, Addis Ababa: IGAD; Respondents 1 and 14. Preventive policy responses are not only hard to achieve because it is difficult to communicate abstract links between structural issues and violent conflict, but their timely implementation hinges on national legislative processes and bureaucracies.78Kebede; Lega; Respondent 30, interview, 21.06.2021, online.

National responses are coordinated by the CEWERUs that are located in ministries or offices of vice presidents. CEWERU heads have access to CEWARN’s country-specific data and may inform government agencies and CSOs to take action.79Respondent 12 and 14. The Strategy Framework aspires to establish subnational CEWERUs and peace committees that, however, must yet be operationalised in most countries, and reinvigorated in Kenya.80IGAD (2020); Omogo.

The multi-agency model of CEWERU Committees, in principle, ensures that CSOs participate in the planning and execution of responses.81Omogo. While Kenya’s and Uganda’s CEWERU Committees regularly meet and involve CSOs, the capacity, activities and participation of CSOs in Ethiopia’s and other CEWERUs have declined owing to government restructuring and intrastate crises.82Kebede; Lega; Respondents 25, 29 and 30. The CEWARN Unit, therefore, promotes the revitalisation of CEWERUs and advocates statutory reporting procedures for Committee meetings and responsive action.83Omogo. Whereas CSOs were integral to CEWARN responses in cross-border clusters, the same must yet be achieved under the Strategy Framework.

Conclusion

CEWARN’s 20 years of experience in partnering with CSOs and the Strategy Framework’s implementation hold lessons for inter(governmental) CEWRS, for CEWARN illustrates the benefits of civil society participation and solutions to pertinent technical, operational and political challenges.

Collecting data on local-level incidents through community monitors across national territories, CEWARN’s experience suggests, is not feasible in most contexts as it would require vast and costly networks of field monitors. NGO reporters, however, may contribute their knowledge to verify, evaluate and contextualise data that is gathered through media monitoring.84Omogo; Respondent 12 and 14.

Thanks to their thematic and country expertise, research institutions can boost the analytical capacity of CEWRS, but scarcely resourced institutes in conflict-affected countries may lack the capacity to periodically produce nationwide sectoral analyses. The sensitivity of sharing conflict-related information between (inter)governmental and non-state agencies is an obstacle to research partnerships that require a sound knowledge management regime.85Kebede; Omogo; Respondents 14, 25 and 29.

CEWARN’s decentralised design and multi-agency CEWERU Committees, in principle, enable the coordination of state organs and CSOs in the planning and implementation of crisis responses and preventive activities. Statutory reporting procedures may be required to ensure that national-level responses are, indeed, implemented and inclusive CEWERU Committees fully operational.86Omogo.

African (inter)governmental CEWRS’ partnerships with CSOs hinge on the latter’s ability to mobilise third-party funding from international development partners to finance their services. Although successful in West Africa, this model has proven unsustainable in CEWARN, where NGO networks that can reliability raise funding and feed into CEWRS must yet be built.87Okechukwu; Omogo; Respondent 11. IGOs, CSOs and development partners must explore alternative funding models or ways to accelerate the development of sustainable NGO networks.

CEWARN is committed to “democratising security” by promoting civic participation in conflict prevention and a human security agenda.88Respondent 29. IGAD countries committed to involve CSOs when approving the CEWARN Protocol and Strategy Framework, but remain hesitant to share information and include non-state actors in managing security matters in practice.89Omogo. Whereas participating CSOs get a seat at the table in CEWERU Committees, a perception that CEWARN leverages CSOs to gather information for states persists among civil society actors.90Interviews with Kebede; Lega; Respondent 21, 18.10.2021, online; Respondents 14, 25 and 30. Building confidence between governments and civil society and opening up civic space for CSOs to engage in conflict prevention are, therefore, essential to bringing the CEWARN strategy and its partnerships to fruition.

Michael Aeby (PhD) is a Research and Teaching Fellow at the University of Basel Centre for African Studies and the Institute for Democracy, Citizenship and Public Policy in Africa at the University of Cape Town.