This article contributes to the ongoing and dynamic debate surrounding the process of continental integration promoted by the African Union (AU). The article investigates how the African integration process has evolved, particularly from the perspective of peace and security, with a specific focus on the case study of the central Sahel. How can the continental approach to the Sahelian crisis be assessed in light of the AU’s longstanding integrative ambitions in the fields of peace and security? Can the instability in the Sahel be considered a missed opportunity for strengthening the continental response to such a significant crisis? This article reflects on these central questions and proposes the Sahel as a potential lens through which to interpret broader continental dynamics.

Walking hand-in-hand: Political integration and peace and security

At a conceptual level, this article analyses the broader process of African political integration by focusing solely on one of the many political, economic, and social sectors, namely, peace and security policies. The justification for this conceptual narrowing lies precisely in the importance that the AU has attributed to these policies in recent years. Achieving greater continental integration in the field of peace and security has always been one of the AU’s fundamental pillars, both in recent times and since its foundation. As a matter of fact, the AU was established with a partially disruptive spirit compared to the past, and in contrast to some of the political orientations promoted by the organisation from which it inherited the role of pan-African supranational entity, the Organisation of African Unity (OUA).[1] Among its many innovations, one of the key principles introduced by the AU was the modification of the old and well-known principle of non-interference among states – a cornerstone of the more intergovernmental political vision that characterised the post-independence years.[2]

From its inception, the AU placed strong emphasis on more integrated peace and security policies, a commitment later consolidated through the creation of the Peace and Security Council (PSC) and the development of the African Peace and Security Architecture (APSA).[3] Thus, the AU tried to take on a more direct role in managing African conflicts in the early 2000s, testing the operational capacity of the APSA in coordination both at the international level – primarily with the United Nations (UN) – and at the regional level with the Regional Economic Communities (RECs). Some notable examples of its activities include the AU Mission in Burundi (AMIB) from 2003 to 2004, the joint AU-UN Mission in Darfur (UNAMID) from 2004 to 2021, the AU Military Operation in Anjouan in 2008, and the AU Mission in Somalia (AMISOM) from 2007 to 2021.[4] These operations – alongside several others not mentioned here – demonstrate how the AU sought to play a decisive role within the continental security landscape, launching missions that, until only a few years earlier, would have seemed difficult to realise, both from an organisational and political standpoint. Over time, these activities helped foster a climate of political optimism, in which increasingly assertive action by the AU in the realm of security was seen as natural – despite certain structural limitations, such as chronic underfunding and significant delays in the development of new institutional frameworks. Indeed, this optimistic climate encouraged the AU to set ambitious and important goals, also reflected in key documents from the past 15 years, such as Agenda 2063.

However, it is important to emphasise that the overall context has changed significantly over the past decade. The strong integrative momentum appears to have weakened and slowed down, particularly by structural limitations within the organisation itself. Chief among these is the issue of financial resources, which remain limited and heavily reliant on international aid. Additionally, the security landscape has evolved rapidly, testing both the operational capacities of the APSA and its coordination with the numerous African regional organisations.[5] In this regard, the security crisis in the Sahel – conventionally dated to 2012 with the outbreak of conflict in Mali – offers a clear example of the challenges discussed above, highlighting the major obstacles to peace and security that confront the AU’s integration process at the

continental level.

Evaluating the AU’s approach to the Sahelian crisis

The Sahel between political instability and insecurity

As is well known within the global academic debate, the Sahel region has suffered from profound political, security, economic, and social instability over at least the past 15 years. A key turning point in Sahelian dynamics can undoubtedly be identified in the outbreak of the Malian crisis in 2012, which triggered significant political and security instability and brought new global attention to the region.[6] Many years later, the situation remains critical and seems to be worsening. The prospects for short-term improvement appear absent. Nevertheless, it is necessary to attempt a concise synthesis of the current state of affairs by arbitrarily dividing the crisis into two main dimensions: the political and the security-related one.

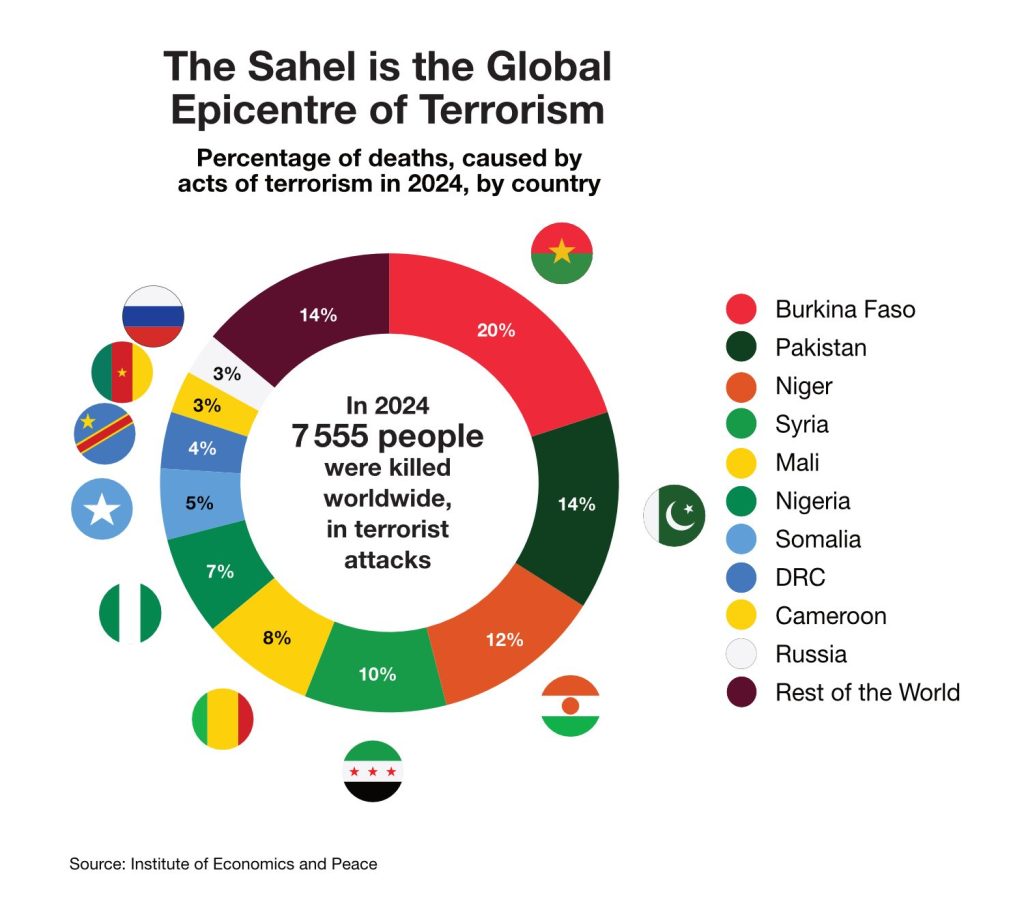

Starting with the latter, it can be stated that the security crisis in the Sahel has increasingly deteriorated in recent years, with a concerning increase in terrorist presence across the territory. Data from 2024 indicate that the Sahel is the setting for more than 50% of all documented terrorist attacks worldwide, with countries such as Burkina Faso, Niger, and Mali consistently ranking among the most affected by terrorist activities globally.[7] With the outbreak of the Malian crisis in 2012, the Pandora’s Box of Sahelian instability was opened. This was initially driven by the National Movement for the Liberation of Azawad and subsequently compounded by the involvement of terrorist groups in the conflict. Despite various stabilisation attempts, both local and international, the crisis has continued to spread across the region. The operations of groups such as Jama’at Nusrat ul-Islam wa al-Muslimin (JNIM) – a coalition of terrorist groups formed in 2017 – and the Islamic State (IS) in the Sahel have grown in both number and intensity over the past decade, exploiting the region’s fragile economic and social fabric to recruit new members and expand their ranks.[8]

However, this dire security situation has not been matched by the political stability necessary to address it. The Sahel has become the epicentre of what, in recent years, has been termed the season of African coups. Just in the past five years, two coups in Mali, two in Burkina Faso, and one each in Chad and Niger have further disrupted the already precarious political balance of the region. These coups have brought to power military juntas with distinctly authoritarian traits and a strong sense of rupture from previous political alignments, particularly with Western international partners.[9]

A process of diplomatic and political disengagement has thus begun between the Sahel states – starting with Mali and later extending to Burkina Faso, Niger, and Chad – and their Western partners, such as France (present in the region through Operation Barkhane for nearly a decade), the European Union (EU), and the UN through its Multidimensional Integrated Stabilisation Mission in Mali (MINUSMA). This shift has been accompanied by intense nationalist propaganda and criticism directed at regional and continental supranational bodies such as the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) and the AU. These organisations have been, and continue to be, portrayed as being under heavy Western influence, dependent on external funding, and disconnected from the genuine interests of the states located in the central Sahel. The outcomes of these political trajectories – beyond the clearly unconstitutional seizures of power – include the suspension of Mali, Niger, and Burkina Faso from the AU[10] and the formal withdrawal of the three countries from ECOWAS, made official in January 2025.[11]

across the territory. Data from 2024 indicate that the Sahel is the setting for more than 50% of all documented terrorist

attacks worldwide. Photo: Adion.

The AU response to the challenge

Although the brief description provided above of the general state of peace and security in the Sahel cannot be considered complete or exhaustive, it remains indispensable and functional to the objective of this article, namely, to investigate the nature of the AU’s response to these dynamics, and how this analysis may lead to broader reflections on the process of African integration within the region. Indeed, the central idea advanced in this article is that, in the specific case of the Sahel, significant limitations in the supranational management of crises remain clearly visible, revealing a substantial gap between the AU’s publicly stated ambitions and its actual capabilities. Continuing with the conceptual distinction established in the previous section between security and politics, it is worth assessing the AU’s impact on the Sahel in recent years.

From a security standpoint, the AU’s role has remained secondary or subordinate. Despite the AU’s repeated declarations in recent years of its intention to play a leading role in shaping peace and security policy across the continent – manifested in ambitious initiatives such as the programme ‘Silencing the Guns by 2020’ – the case of the Sahel demonstrates a significantly different reality. The first African-led response to the Malian crisis of 2012 came with the establishment of the African-led International Support Mission to Mali (AFISMA), coordinated by ECOWAS and supported by the AU, which deployed troops in Mali from early 2013. However, after a few months, the mission’s control was transferred to the UN, resulting in the creation of MINUSMA. Subsequently, in August 2013, the AU established the AU Mission for Mali and the Sahel (MISAHEL), which was mandated to support MINUSMA’s activities and serve as the implementing body for AU decisions in the Sahel context.[12]

From the onset of the crisis to the present day, the AU’s activities in the Sahel have faced persistent challenges related to implementation and, in some cases, relevance. The AU has consistently expressed its support for the initiatives of international actors on the ground – particularly the EU and UN – with whom it maintains strong partnerships. Nonetheless, direct and targeted actions aimed at enhancing the AU’s role as a key actor in the crisis have been limited or poorly executed. Over the years, the PSC has held numerous meetings, yet these have rarely resulted in concrete outcomes in terms of implementation or the restoration of meaningful political and diplomatic dialogue.[13]

On the contrary, in recent years, a concerning trend has emerged in the form of a decline in the number of PSC sessions dedicated to countries or the broader Sahel region – a decrease in attention that does not align with the continued rise in insecurity, terrorist activities, and civilian and military casualties. Despite the political emphasis placed on mechanisms such as the Early Warning System, the Panel of the Wise (PoW), and the African Standby Force (ASF), none have been effectively applied to the Sahel context – despite the region representing a fitting and urgent testing ground.

The Sahel has witnessed the proliferation of numerous military interventions involving France, the EU, UN, and various ad hoc coalitions – none of which have been led or managed by African, particularly supranational, institutions. On one hand, AFISMA was quickly placed under UN control. On the other hand, the AU’s complementary mission, MISAHEL, has never played a significant role, as evidenced by its frequent absence from public debate and limited visibility.

Another instrument that could have been employed for the first time in a suitable peace and security context is the ASF. However, from its inception, the ASF has been plagued by operational, financial, and political challenges. Although the AU declared the ASF fully operational in 2016, and its deployment was encouraged by the PSC, no ASF contingents have ever been deployed in the Sahel, despite the PSC declaration to send 3 000 troops in 2020. Nevertheless, given the delays in implementation and the proliferation of both local and international peace and security initiatives, questions arise as to the actual necessity and utility of such a force in today’s fragmented and chaotic Sahel landscape.[14]

Next in order, even from a political and governance perspective, the AU’s role in the region remains limited. Politically, the AU’s most significant action has been the suspension of member states where military juntas have seized power through unconstitutional means. This has led to a rapid deterioration in relations between the AU and states such as Mali, Burkina Faso, and Niger – although it has confirmed a commitment to the organisation’s democratic principles. Indeed, this deterioration is also the result of ambiguity in responses from the AU when facing specific crisis situations, such as in Niger in 2023, where the AU’s response was splintered. Indeed, while the AU Commission firmly stated its rapid support for ECOWAS decisions, even the threat of possible military intervention, the PSC moved more cautionally, trying to descalate the situation.[15]

These decisions exemplify the AU’s emphasis on its political principles, yet they may also represent a double-edged sword in terms of its influence and perception in the region. By adhering to firm and uncompromising policies – its own and those of ECOWAS – without undertaking adequate diplomatic efforts to maintain open channels of dialogue, the AU has arguably contributed to the isolationism of Sahel states, which have entrenched themselves further in their positions. This has resulted in a marked loss of influence in the region (to the benefit of new international actors). Symbolically, the formation of the new regional bloc, the Alliance of Sahel States (AES), by Mali, Burkina Faso, and Niger (characterised by a strong critique of the traditional model of regional and continental integration), is illustrative of this.

Amid this political and diplomatic upheaval, another key APSA mechanism that could have facilitated improved institutional dialogue is the PoW, originally established to enable high-level diplomatic engagement in specific crises through the expertise and authority of its members. However, the PoW’s presence in the central Sahel over the past decade has been basically non-existent, despite the region’s political volatility and the evident need for structured diplomatic exchange.[16] The same is true for the Continental Early Warning System (CEWS), one of the flagship mechanisms of the AU’s peace architecture, designed to function in both security and governance domains. Although the PSC has repeatedly acknowledged the need to improve the system’s implementation, CEWS has proven largely ineffective in the Sahel, failing to anticipate or prepare for political dialogue ahead of successive coups and unable to provide early analysis of escalating security risks, particularly in the Liptako Gourma region. The CEWS could potentially serve as a critical tool for an AU that has often appeared ill-prepared to manage sudden and complex crises such as those witnessed in the Sahel.[17] Enhancing its effectiveness and operational readiness remains one of the AU’s most pressing challenges.

Heads of state of the Alliance of Sahel States, Captain Ibrahim Traoré of Burkina Faso, General Abdourahamane Tiani of Mali and Assimi Goita of Niger. Photo credits: Kremlin, Sule Barma and Lamine Traoré/VOA.

Recommendations

Based on the above analysis, the following recommendations are made:

- Rebuild diplomatic dialogue with the central Sahel states to establish a new partnership that enables a continent-wide response to the region’s multiple challenges.

- Identify the appropriate pathway to foster greater integration in addressing peace and security challenges across the African continent by enhancing the AU’s relevance in crisis contexts through more active diplomacy and better coordination of the various interests at play.

- Invest in the development of mechanisms, such as the CEWS, which enable preventive political influence and greater relevance in contexts of emerging crises.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this article does not aim to offer a critical assessment of the AU’s responses in terms of its actual capacity, which, due primarily to financial constraints, unfortunately, remains inadequate to address complex challenges such as those previously outlined. However, attention must also be drawn to the excessively ambitious goals presented in public discourse, such as the ‘Silencing the Guns by 2020’ initiative, which are, inevitably, unattainable when one considers the tools currently at the AU’s disposal.

Moreover, even in areas where the AU could have more feasibly maintained greater relevance and influence, namely, political and diplomatic dialogue, its response has fallen significantly short of expectations. The political rupture with the core Sahel states constitutes a major crisis for both regional and continental integration. In recent years, relations have been marked by tensions and superficial engagement. Although the PSC has recently initiated informal consultations with the governing authorities of Mali, Niger, and Burkina Faso, the situation remains highly uncertain.

Unfortunately, the current state of affairs in the Sahel offers little ground for optimism. What is clear, however, is that the major challenges facing the Sahel, such as combating climate change or countering the increasingly pervasive threat of terrorism, will necessarily require responses at the regional and continental level to be effectively addressed. In this sense, the process of integration should undergo a renewed impetus.

References

[1] Wallerstein, Immanuel Maurice (2005), Africa: The Politics of Independence and Unity, Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press.

[2] AU (2000) Constitutive Act of the African Union, Available at: https://au.int/sites/default/files/treaties/7758-treaty-0021_-_CONSTITUTIVE_ACT_OF_THE_AFRICAN_UNION_E.pdf [25 March 2025].

[3] Karbo, Tony, and Tim Murithi (2017) The African Union: Autocracy, Diplomacy and Peacebuilding in Africa, London: Bloomsbury Publishing.

[4] Khadiagala, Gilbert (2023) ‘The African Union Peace and Security Architecture (APSA) in the Search for Peace and Security: The Record over the Past Twenty Years’, Comparativ 33(1): 53–69, https://doi.org/10.26014/j.comp.2023.01.04

[5] Mattheis, Frank; Dimpho Deleglise; and Ueli Staeger (2023) ‘African Union: The African political integration process and its impact on EU-AU relations in the field of foreign and security policy’, European Parliament, May, Available at: https://movimentoeuropeo.it/images/Documenti/EP_EXPO_STU2023702587_EN_EU-AU.pdf [20 March 2025].

[6] Boserup, Rasmus Alenius, and Luis Martínez (2018) Europe and the Sahel-Maghreb Crisis, Copenhagen: Danish Institute for International Studies (DIIS).

[7] Institute for Economics and Peace (2025) ‘Global Terrorism Index 2025’, Available at: https://www.economicsandpeace.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/Global-Terrorism-Index2025.pdf [28 March 2025].

[8] ACLED and GI-TOC (2024) ‘Non-state armed groups and illicit economies in West Africa: Building armed group legitimacy’, Available at: https://acleddata.com/2024/12/11/non-state-armed-groups-and-illicit-economies-in-west-africa-building-armed-group-legitimacy [28 March 2025].

[9] Matteo Peccini (2025) The Security-Development Nexus in the EU’s Policies Towards the Sahel. A Critical Appraisal of the Malian Case, FUP, Available at https://books.fupress.it/catalogue/the-security-development-nexus-in-the-eus-policies-towards-the-sahel/15860 [12 April 2025].

[10] African Union (2025) ‘Communique of the 1212th Meeting of the PSC Held on 20 May 2024, on the Updated Briefing on the Political Transition in Burkina Faso, Gabon, Guinea, Mali, and Niger-African Union – Peace and Security Department,’ Available at https://www.peaceau.org:443/en/article/communique-of-the-1212th-meeting-of-the-psc-held-on-20-may-2024-on-the-updated-briefing-on-the-political-transition-in-burkina-faso-gabon-guinea-mali-and-niger. [12 April 2025].

[11] IISS (2024) ‘The Withdrawal of Three West African States from ECOWAS’, Available at https://www.iiss.org/publications/strategic-comments/2024/06/the-withdrawal-of-three-west-african-states-from-ecowas/. [12 April 2025]

[12] Gnanguenon, Amandine (2014) ‘Mission Analysis. African Union Mission for Mali and the Sahel (MISAHEL)’, Institute for Security Studies (ISS), Available at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/330823532_Mission_analysis_African_Union_Mission_for_Mali_and_the_Sahel_MISAHEL_PSC_Peace_and_Security_Council_Report_Institue_for_Security_Studies_Addis_Abeba_2014_Issue_58_May_pp_2-5 [2 April 2025].

[13] Amani Africa (2025) ‘Africa in a New Era of Insecurity and Instability: The 2024 Review of the Peace and Security Council’, PSC Yearly Reports, Available at: https://amaniafrica-et.org/wp-content/uploads/Africa-in-a-New-Era-of-Insecurity-and-Instability-The-2024-Review-of-the-Peace-and-Security-Council.pdf [11 April 2025].

[14] ISS (2024) ‘The African Union Can Do Better for the Sahel’, Available at: https://issafrica.org/pscreport/psc-insights/the-african-union-can-do-better-for-the-sahel [11 April 2025].

[15] Amani Africa (2024) ‘The-Peace-and-Security-Council-in-2023-The-Year-in-Review.,’ PSC Yearly Reports, Available at https://amaniafrica-et.org/wp-content/uploads/The-Peace-and-Security-Council-in-2023-The-Year-in-Review.pdf. [11 April 2025].

[16] African Union Political Affairs, Peace and Security Department (2023) ‘Communiqué of the 1142nd Meeting of the Peace and Security Council Held on 3 March 2023, on the Briefing by the Panel of the Wise on Its Activities in Africa.,’ Available at: https://Papsrepository.Africa-Union.Org/Handle/123456789/1833, 2023, http://akb.au.int//handle/AKB/97081. [11 April 2025].

[17] Amani Africa (2023) ‘The-Peace-and-Security-Council-in-2022-The-Year-in-Review’, Available at https://amaniafrica-et.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/02/The-Peace-and-Security-Council-in-2022-The-Year-in-Review.pdf. [12 April 2025].