Introduction

There is a considerable popular feeling of exclusion and perceived sense of injustice among various units of the Nigerian federation – a situation that has led to alienation, suspicion and apprehension among various groups in the country. Over time, different groups have pursued separatist ambitions in Nigeria – some examples are Ogoni nationalism and the Boko Haram insurgency. This article focuses on Nigeria’s unresolved ethnic tensions and suspicions of domination that led to the declaration of the state of Biafra, leading to the Nigerian civil war between 1967 and 1970, and the subsequent persistent agitation for an independent state of Biafra since the end of the war.

Origin of the Problem

In 1914, the protectorates of Northern Nigeria and Southern Nigeria were amalgamated to form a single colony and protectorate of Nigeria by the British colonial administration. This amalgamation of 250 diverse ethnic groups and two separate provinces is related to the first military coup in Nigeria and the subsequent declaration of the state of Biafra. This was a forceful merger of not only different identities and religions; it was also a clash of political class, since both provinces had different administrative systems.1 A colonial constitution divided Nigeria into three political regions in 1947: east, north and west. The north, which is the largest area, was predominately Hausa-Fulani, Igbos were the majority in the east and Yorubas dominated the west.2 The territorial and ethnic identities of the colonial system were still in place on the eve of independence.3 The limited integration of cultures resulted in rivalry and the formation of political parties that were largely regional and based on ethnic identities: the Action Group (AG) in the west, the Northern People’s Congress (NPC) in the north and the National Council of Nigeria and the Cameroons (NCNC) in the east. The parties also had different ideologies – for example, the NPC and the AG favoured a loose confederacy, while the NCNC preferred a unitary/united structured country.

The years leading to, and after, independence were tense, as they were dominated by the quest for ethnic dominance by the three political entities. Politicised ethnicity and competition over scarce resources led to a high degree of nepotism and tribalism at the expense of nationhood. This competition and insecurity eventually peaked in 1966 with the demise of the first republic.

On 15 January 1966, Chukwuma Kaduna Nzeogwu led the first-ever military coup in Nigeria. The coup plotters claimed they wanted a better and united Nigeria that offered equal opportunity to its citizens without regional or ethnic considerations and nepotism, large-scale looting of public wealth, persistent poverty of the people, insecurity, the Tiv riots4 and the western region’s consistent violent protests.5 While there have been various assertions about the details or cause of the coup, this article is concerned with the outcome of the coup in relation to the suspicions from various regions and the eventual birth of Biafra.

The jubilations that initially greeted the coup quickly waned after a sudden realisation of the sectional and imbalanced composition of the coup leaders, as well as the nature of the assassination and killings of prominent politicians and military officers as a result of the coup. The coup planners were Kaduna Nzeogwu (Igbo), Adewale Ademoyega (Yoruba), Emmanuel Ifeajuna (Igbo), Timothy Onwuatuegwu (Igbo), Chris Anuforo (Igbo), Humphrey Chukwuka (Igbo), Don Okafor (Igbo), Ben Gbulie (Igbo), Emmanuel Nwobosi (Igbo) and Ogbo Oji (Igbo).6 Nine of the 10 coup initiators were Igbo from the then eastern region of Nigeria, and one Yoruba from the western region. The coup resulted in the assassination of Ahmadu Bello (Fulani), the premier of northern Nigeria; Samuel Ládòkè Akíntọ́lá (Yoruba), the premier of the western region; Abubakar Tafawa Balewa (Baggara), prime minister of Nigeria; and Festus Okotie-Eboh (Itshekiri), federal minister of finance. The senior officers who were assassinated during the coup were Zakariya Maimalari (Kanuri), Samuel Ademulegun (Yoruba), Abogo Largema (Kanuri), James Pam (Berom), Arthur Unegbe (Igbo) and Ralph Shodeinde (Yoruba).7 Although the coup might have been planned with the best of intentions, its outcome looked to target mostly non-Igbo ethnic groups. While leaders from the northern, western and mid-western regions were killed during the coup, no Igbo leaders were assassinated. Nnamdi Azikiwe (Igbo), president of Nigeria, had at the time gone on a prolonged medical trip to London.8

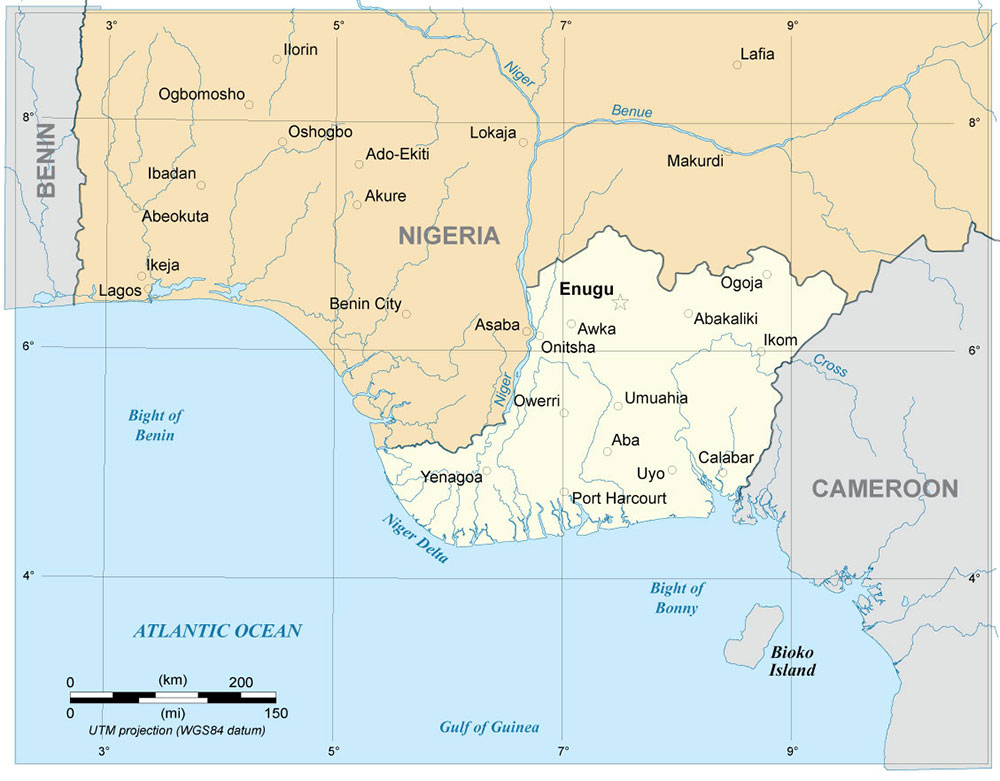

The coup succeeded in Kaduna (the northern region capital), failed in Lagos (the federal capital) and Ibadan (the western regional capital) and barely took place in Benin (the mid-western capital) and Enugu (the eastern capital). In the absence of the prime minister, acting president Nwafor Orizu was compelled to hand over to the military, which was headed at the time by General Johnson Aguiyi-Ironsi, an officer from the eastern region.

Whatever suspicions people had were validated by Ironsi’s policies. He failed to address the accusation that the coup was sectional, and refused to bring the leaders of the coup to trial. He did not establish a broad-based government, preferring instead to work with a small team – who incidentally were Igbo. In spite of a one-year freeze on promotions, he elevated 21 officers to the rank of lieutenant-colonel – 18 of whom were Igbo.9 Against all advice, Ironsi promulgated Decree Number 34 of 1966, which abrogated the federal system of government and substituted a unitary system, opening up the northern civil service to Igbo officers for the first time. Given the already charged atmosphere, this action reinforced northern fears. As the north was less developed than the south, a unitary system could easily lead to southerners “taking over control of everything”.10 Political violence began in Kano, Sokoto, Katsina, Maiduguri and other areas in the north in support of a secession bid called “araba”. It was at the height of the northern opposition to unitarism that the countercoup of July 1966 took place. Top-ranking Igbo officers – including Ironsi – lost their lives, and northern dominance was restored.11

Lieutenant-Colonel Yakubu Gowon was appointed head of state by the July 1966 coup conspirators. Hassan Katsina, military governor of the northern region, David Ejoor, military governor of the mid-west region, and a group of leading Yoruba leaders all agreed to accept Gowon as the head of state. However, Chukwuemeka Odumegwu-Ojukwu, the governor of the eastern region, insisted that the military hierarchy be sustained. Ojukwu wanted Babafemi Ogundipe, who was the most senior after Ironsi, to take over leadership. However, Ogundipe was unable to assert his authority over the troops, especially the coup plotters, who clearly wanted Gowon to take over leadership.12 This fall-out led to a sequence of events that resulted in the Nigerian civil war.

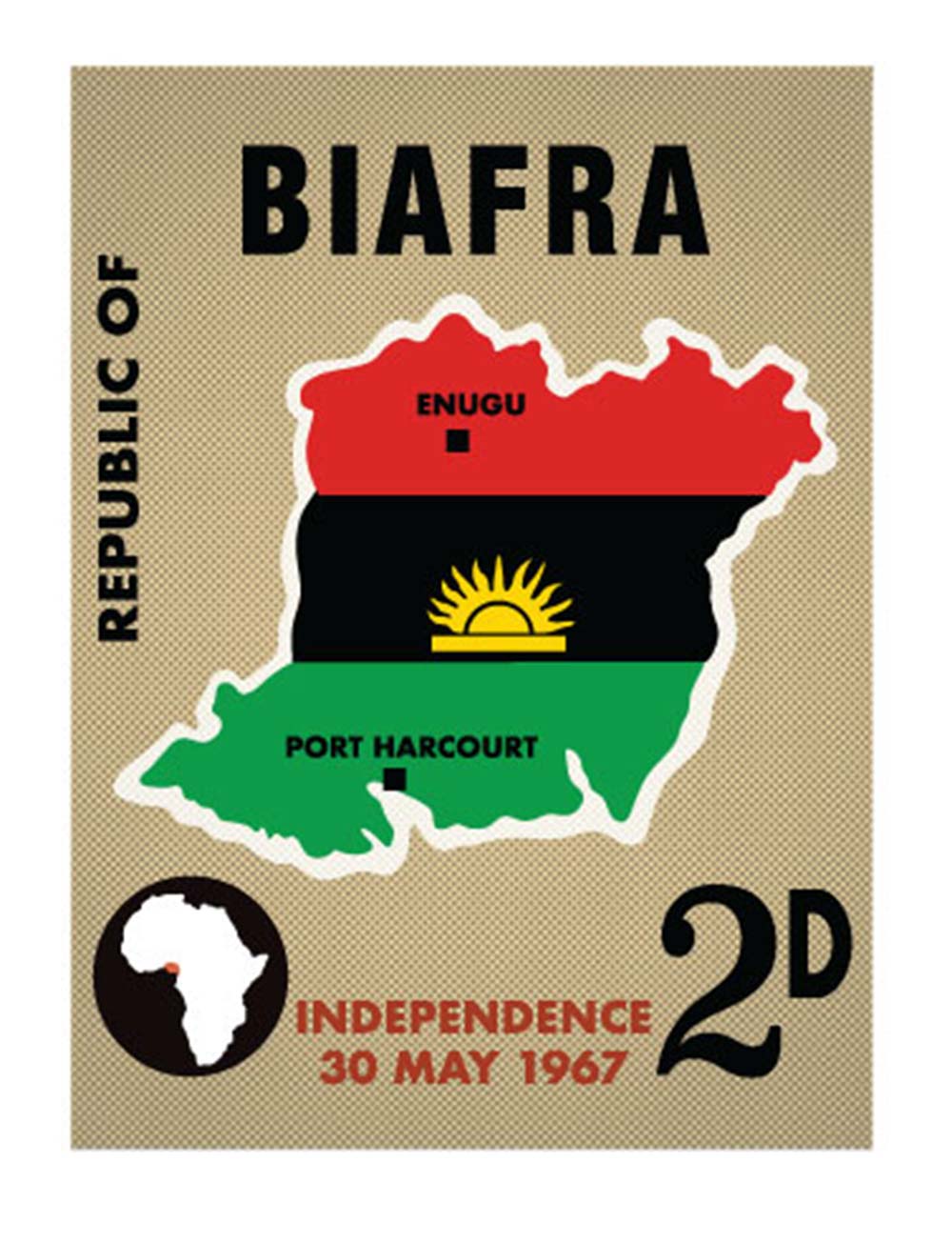

Although Gowon abrogated Ironsi’s unification decree and reinstated the federal system, this did not pacify northerners, as a massive pogrom against Igbos in the northern region at the time led to a large exodus of Igbos to the eastern region. Ojukwu eventually relaxed his position and sent delegates to an ad hoc constitutional conference, initiated by Gowon, to deliberate the country’s political future. The regional debate ended abruptly as killings of Igbos in the north increased – this time, the killings were organised by soldiers and civilians.13 In October 1967, Ojukwu asked all non-Igbos to leave the eastern region and both sides started arming.14 A summit of military leaders was organised in Aburi, Ghana in January 1967 to resolve the disagreements. The Aburi Accord became a source of contention with no comprehensive agreement. In anticipation of eastern secession, Gowon moved quickly to weaken the support base of Ojukwu’s eastern region by creating 12 new states that contained minority groups, who had demanded the creation of separate states since the 1950s. East-Central State, South-Eastern State and Rivers State were carved out of the eastern region. Gowon rightly envisaged that non-Igbo eastern minorities (Rivers State and South-Eastern State) – who had large reserves of oil and access to the sea – would not support the Igbos, given the prospect of having their own states should the secession effort fail.15

On 26 May 1967, Ojukwu called a meeting of the Advisory Committee of Chiefs and Elders on the situation, and sought their decision on the next move. The following day, on 27 May 1967, the consultative forum mandated Ojukwu to declare secession and on 30 May 1967, he declared independence as the Republic of Biafra – named after the Bight of Biafra, a bay on the country’s Atlantic coast.16

The federal government took no immediate steps to attack the eastern region, but rather declared “police action”. Ogoja, Nsukka and the oil terminal in Bonny were captured by federal forces in July 1967. The “police action” didn’t last long, as it unfortunately resulted in a full-scale war after Biafran forces retaliated with a surprise invasion in the mid-western region on 9 August 1967.17 This led to a 30-month civil war between the federal government and the secessionist state of Biafra. The war ended when Ojukwu fled the country and his deputy, Phillip Effiong, surrendered to the Nigerian forces.18

The war, which remains a threat to Nigeria’s unity, resulted in over a million deaths.19 The federal government under Gowon declared a policy of “no victor, no vanquished” and instituted the 3Rs – rehabilitation, reconstruction and reintegration. The implementation of the 3Rs is alleged to have been problematic, as no extensive infrastructural reconstruction was undertaken in the south-east region. In addition, the administrative policy of giving only 20 pounds to former Biafrans, regardless of how much they had in their accounts before the war, was criticised locally and internationally.

Biafran Agitation and the Quest for Secession

It is not uncommon for groups who have fought and lost a secession war to nurse desires for independence. Shared victimhood makes for easy mobilisation of support. The Igbos continued to feel alienated from Nigeria after the civil war. They believed they had been excluded from the political and socio-economic mainstream of the country, and the clamour for a separate existence from Nigeria continued to gain momentum. This eventually led to the establishment of the Movement for the Actualization of the Sovereign State of Biafra (MASSOB) in 1999. MASSOB, described as a non-violent separatist movement, with its philosophy hinged on the principle of non-violent conflict as propagated by Mahatma Gandhi, was founded by Ralph Uwazuruike, a lawyer, on 13 September 1999. MASSOB advertised a 25-stage plan through which its goal for peaceful secession from Nigeria would be achieved.20 MASSOB successfully mobilised Igbos in the country to shut down their businesses for a day on 26 August 2004, and embarked on demonstrations in Canada, Germany, Italy and France.21 Their activities provoked the government and led to several arrests of Uwazuruike and his followers for unlawful gatherings and the disruption of public peace. In July 2000, Uwazuruike was arrested for storming the 36th Organisation of African Unity (OAU) Summit in Lomé.22 He was again arrested and arraigned for treason in Abuja in 2005. He was released on bail in 2007 after some political interventions, and finally discharged and acquitted with his members in 2011, during the Goodluck Jonathan administration. The movement has since lost steam, as it failed to gather the support of the south-east governors amid concerns in certain quarters that the movement was too politicised.

Another group, the Biafran Zionist Movement (BZM), was founded in 2010 by a United Kingdom-based lawyer, Benjamin Onwuka, who said it was founded to give “seriousness” to the Biafran dream. The group submitted an application to United Nations (UN) Secretary-General Ban Ki-Moon for observer status for the Republic of Biafra in 2012.23 Onwuka’s attempt to declare himself as the leader of the new Biafran Republic in a live broadcast resulted in a gun battle with the police, and his (and his members’) subsequent arrest. They were charged with treason but granted bail.24 Onwuka and his members were again arrested in 2018 while marching to Enugu State Government House to hoist the Biafran flag. They are now on trial.25

Nigerian-British Nnamdi Kanu created the Indigenous People of Biafra (IPOB) group, a more radical breakaway faction from MASSOB. Although the group existed before Muhammadu Buhari became president in 2015, its agitation took on an aggressive dimension a few months after the new government was inaugurated. Kanu’s broadcasts on Radio Biafra from London quickly gained popularity, especially among Igbo people. Unlike MASSOB, IPOB appears to encourage violent conflict. For example, Kanu was seen on video footage seeking arms at the World Igbo Congress in the United States. He claimed that the only language the Nigerian government understands is war, and that he was going to regroup and surprise Nigerians.26

Kanu was arrested for treason in October 2015. He was granted bail in April 2017 on health grounds, on condition that he would not engage the public on matters related to Biafran independence. While he was in prison, an Amnesty International report27 accused Nigerian forces of killing over 150 pro-Biafra activists.28 After his release, Kanu violated his bail conditions and continued his verbal war against the government, and his group was accused of harassment in some south-east states. In reaction, some northern youth groups declared “war” against all Igbos residing in the north, demanding they leave the area within three months.

Northern leaders intervened and mounted pressure on the youth to withdraw the threat, while the Nigerian army deployed a special formation, Operation Python Dance II,29 to the south-east states to curb the security situation there. The troops allegedly invaded Kanu’s family home and shot and arrested some IPOB members during the attack.30 The whereabouts of Kanu and his parents during and after the invasion were not made public until he resurfaced in 2018. The South East Governors Forum subsequently banned the activities of IPOB after an emergency meeting in Enugu, and it also advised that all grievances be channelled through the chairman of the South East Governors Forum.31 President Buhari also began the process of proscribing IPOB in the country after accusing the group of terrorist activities, such as setting up parallel military and paramilitary organisations, clashing with the national army, and mounting roadblocks to extort people, among others.32 The attorney-general of the federation and minister of justice, Abubakar Malami, filed an ex parte motion, asking the court to ban the activities of IPOB and declare it a terrorist organisation. The Federal High Court granted the motion and consequently ordered the proscription of the group.33

It is important to note that there are many contradictions in the motives for the Biafran agitation. Some people use it as bargaining chips and some for personal gains, while some sincerely want secession. A good majority of Igbos in the south-east and other parts of the country do not support the movement, and would rather have a fair and equitable Nigeria than a separate state of Biafra.

The proscription of IPOB with the support of the south-east governors has subdued the agitation. However, it is important for the government, in partnership with stakeholders in the region, to take proactive steps to address the underlying factors behind the agitation to avoid a resurgence.

Moving Forward

Strength in Diversity

Nigeria is inhabited by people of diverse languages, religions and customs, with divergent human and natural resources. This diversity defines the uniqueness of its statehood. The resources, innovation and creativity that comes from different parts of the country should be harnessed for the commonwealth of Nigeria. There should be inclusion, recognition and acceptance of diversity and the value that different groups contribute to the country. There is a need for fair and equitable development and policies that ensure equity and equality. Nigeria’s position in the international community is derived from its diversity and population. Developed countries in Western Europe came together to establish the enviable European Union for peace and prosperity, and this shows the strength possible in diversity.

Dialogue

It has been over 50 years since the civil war resulted in over a million deaths. There is a need to reflect on such brutality by citizens against each other, and the reasons for the resurgent agitation for the state of Biafra five decades after the war. There is a need to know the roots of the agitation, understand the claim of unequal treatment in terms of federal appointments and infrastructure development, and allegations of victimhood and poor responses from the government. These issues have to be discussed by the government and stakeholders in the region. The government should create a forum for discussion on what needs to be done for Igbos to feel that they belong and are not alienated in Nigeria.

Purposeful Regional Leadership

The leaders in the south-east region must improve governance at all levels. There is a need to initiate policies and projects that will help to satisfy the daily economic, social and political needs of the people. The south-east region’s combined internally generated revenue (IGR) is less than that of Ogun State in the south-west. High reliance on federal allocations and lack of investment and innovation in the south-east – which is the most densely populated region in Nigeria – is breeding economic frustration and resentment against the government. It is important for the south-easterners to hold their leaders accountable and ensure that they improve the security and economy of the region, fight for the region’s equitable share from the centre and, most importantly, not distance itself from the pulse and aspirations of the people.

Conclusion

Following the proscription of IPOB by the south-east governors and the federal government, and the restoration of peace to the region, the time is ripe for the federal government to focus on the south-east region. The government should establish a transparent commission of inquiry to look into various issues in the Biafran agitation. The commission should investigate the activities of pro-Biafra groups and government agencies, especially the role of the police and military in extrajudicial killings and human right abuses. The government should prosecute those implicated in the abuse and killings of Biafran agitators, and consider granting amnesty to Biafran agitators in the interest of national unity.

The government, in collaboration with leaders from the south-east region, should establish a reconciliation forum for pro-Biafra groups to express their grievances, and to advise the government on how best to address grievances. It is important to note that the civil war ended after Biafra surrendered and not after a peace agreement, as is the norm after most civil wars. A reconciliation forum will hopefully help to resolve conflict left over from the past and recreate a sense of national unity.

Finally, although self-determination is a cardinal principle in international law and is enshrined in the AU and UN charter, it has to be done in accordance with the law and international best practices. As such, agitators such as IPOB, MASSOB and BZM must desist from acts that endanger lives and property. Most importantly, their cause should be focused on the interests of those whom they wish to protect, and they should ponder this crucial question: Is a landlocked Biafra surrounded by a possibly hostile Nigeria the best option for Igbos?

Endnotes

- Ray, Jacob (2012) ‘A Historical Survey of Ethnic Conflict in Nigeria’, Asian Social Science, 8 (4), Available at:<http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.663.3342&rep=rep1&type=pdf> [Accessed 6 September 2019].

- Ibid.

- Heerten, Lasse and Moses, A. Dirk (2014) ‘The Nigeria-Biafra War: Postcolonial Conflict and the Question of Genocide’, Journal of Genocide Research, 16 (2-3), pp. 169–203, Available at: <https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/14623528.2014.936700> [Accessed 6 September 2019].

- Tiv is a minority group in the north that formed an alliance with the Action Group of Western Nigeria through its popular United Middle Belt Congress. The regional government was not happy with their lack of support and deprived them of amenities. The Tiv resented this deprivation and hardened their opposition to the regional government, which resulted in violence.

- Awoyokun, Damola (2016) ‘British Secret Files on Nigeria’s First Bloody Coup, Path to Biafra’, The News, 12 June, Available at: <https://www.thenewsnigeria.com.ng/2016/06/british-secret-files-on-nigerias-first-bloody-coup-path-to-biafra/> [Accessed 15 September 2017].

- Siollun, Max (2005) ‘The Inside Story of Nigeria’s First Military Coup – Part 2’, Available at: <http://www.gamji.com/article6000/news6574.htm> [Accessed 6 September 2019].

- Abdulrahman, Ajibola (2014) ‘The Impact of Military Rule on Nigeria’s Nation Building, 1966–1979’, Available at: <https://www.iiste.org/Journals/index.php/HRL/article/download/18212/18587> [Accessed 15 September 2017].

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Metz, Helen (1991a) ‘Nigeria: A Country Study’, Available at: <http://countrystudies.us/nigeria/> [Accessed 17 September 2017].

- Ibid.

- Yakasai, Tanko (1995) ‘The Fall of the First Republic and Nigeria’s Survival of the Crisis and Civil War of 1960-1970’, Inside Nigerian History 1950-1970: Events, Issues and Sources, Ahmadu Bello University Press: Nigeria.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Metz, Helen (1991a) op. cit.

- Yakasai, Tanko (1995) op. cit.

- Helen, Metz (1991b) ‘Nigeria: A Country Study’, Available at: <https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/f8e9/45c31bf22d313b46acc9dd0dea7606f5ec96.pdf> [Accessed 6 September 2019].

- Abdulrahman, Ajibola (2014) op. cit.

- Helen, Metz (1991b) op. cit.

- Nnamdi, Felix (2014) ‘Biafra: Undying Passion for Secession’, The News, 23 June, Available at: <https://www.thenewsnigeria.com.ng/2014/06/biafra-undying-passion-for-secession/> [ Accessed 20 April 2019].

- Thompson, Olasupo; Ojukwu, Chris and Nwaorgu, O.G.F. (2016) ‘United We Fall, Divided We Stand: Resuscitation of the Biafra State Secession and the National Question Conundrum’, Available at: <https://www.transcampus.org/JORINDV14JUN2016/24.pdf> [Accessed 20 April 2019].

- Eze, Ikechukwu (2000) ‘Nigeria: MASSOB Leader to Face Trial in Togo’, Vanguard, 17 July, Available at: <https://allafrica.com/stories/200007170330.html>.

- Oji, Chris (2012) ‘The Biafra Zionist Movement’, The Nation, 6 November, Available at: <https://thenationonlineng.net/the-biafra-zionist-movement/> [Accessed 21 April 2019].

- Oluokun, Ayorinde (2014) ‘Biafra Group’s Attempt to Seize TV Station Foiled’, PM News, 5 June, Available at: <https://www.pmnewsnigeria.com/2014/06/05/biafra-groups-attempt-to-seize-tv-station-foiled/> [Accessed 21 April 2019].

- Nzomiwu, Emmanuel (2018) ‘Biafra Day: Police Confirm Arrest of BZM Leader, Benjamin Onwuka’, Independent, 30 May, Available at: <https://www.independent.ng/biafra-day-police-confirm-arrest-of-bzm-leader-benjamin-onwuka/> [Accessed 21 April 2019].

- Thompson, Olasupo; Ojukwu, Chris and Nwaorgu, O.G.F (2016) op. cit.

- Amnesty International (2016) ‘Biafra Activists Killed in Chilling Crackdown’, Available at: <https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/news/2016/11/peaceful-pro-biafra-activists-killed-in-chilling-crackdown/> [Accessed 6 September 2019].

- Ashley, Bybee (2017) ‘The Indigenous People of Biafra: Another Stab at Biafran Independence’, Available at: <https://www.ida.org/idamedia/Corporate/Files/Publications/AfricaWatch/africawatch-November-9-2017-vol17.pdf> [Accessed 21 April 2019].

- Njoku, Lawrence (2017) ‘Whereabouts of Kanu, Father, Mother Unknown’, The Guardian, 15 September, Available at: <https://guardian.ng/news/whereabouts-of-kanu-father-mother-unknown/> [Accessed 21 April 2019].

- Ibid.

- Uzodinma, Emmanuel (2017) ‘South-east Governors Proscribe IPOB’, Daily Post, 15 September, Available at: <https://dailypost.ng/2017/09/15/breaking-south-east-governors-proscribe-ipob/> [Accessed 21 April 2019].

- Waranmi, Urowayino (2017) ‘Buhari Begins Process of IPOB Proscription-FG’, Vanguard, 20 September, Available at: <https://www.vanguardngr.com/2017/09/buhari-begins-process-ipob-proscription-fg/> [Accessed 21 April 2019].

- Adesomoju, Ade (2017) ‘Court Proscribes IPOB, Declares it Terrorist Group’, PUNCH, 20 September, Available at: <https://punchng.com/breaking-court-proscribes-ipob/> [Accessed 24 April 2019].