Evaluating two community security and arms control (CSAC) projects piloted by UNAMID in Darfur, Sudan

Executive summary

This policy and practice brief (PPB) focuses on the lessons learnt from two pilot community security and arms control (CSAC) projects in Darfur, Sudan, implemented by the United Nations-African Union Hybrid Operations in Darfur (UNAMID). The lessons are drawn from the evaluation of the two pilot CSAC projects that reflect the perspectives of various participants and partners in the projects. The CSAC project was initiated after the government’s contentious attempt to gather civilian weapons in the Darfur region in 2017 and after mandatory civilian disarmament in 2020 with a focus on internally displaced persons (IDP) camps.

Among other things, according to the results of the evaluation of the projects, inclusive participation and bottom-up execution allowed for the effective use of local resources and helped mobilise community support for the projects. For such a politically sensitive undertaking, Project Management Committees (PMCs) were formed, and a public information and communications plan was developed to mobilise political and public support. Beneficiaries of the project preferred individualised support over group support to exchange firearms, which critics viewed as a buy-back programme and compensation for illegal possession. The evaluation also found that a community development approach is preferred for similar operations to address these perceptions and strengthen community cohesion and stability. Among other suggestions, the evaluation recommended a national policy to direct the implementation of future comprehensive small arms and light weapons (SALW) control operations in Darfur.

Background

This PPB examines the implementation of two UNAMID-supported pilot CSAC projects in Azoum Locality and West Jebel Mara Locality in Central Darfur. The lessons learnt from reports, field visits, monitoring and evaluation (M&E), and other materials highlight best practices and suggestions that may guide future initiatives to reduce the proliferation of arms and ammunition.

Sudan has no official data on the number of illicit civilian weapons in circulation in the country. According to an online research report, the number of weapons in circulation in Darfur is unknown, but it was estimated in 2017 that there are 6.6 guns for every 100 people and 2.76 millionweapons in total in Sudan.[1] The urge for Darfuris to protect themselves in the absence of government protection and the rule of law led to an exponential increase in civilian firearm ownership in the region.

Setting the Darfur Conflict and Arms Proliferation in Context

Asserting alienation and social, political and economic exclusion, various armed factions in Darfur began fighting the Government of Sudan (GoS) in 2003. Since then, violence has continued in different forms, such as conflicts between herders and farmers, inter-communal conflicts, and clashes between rival militias. Conflicts have increased the spread of SALW and ammunition, posing significant threats to human security and long-term stability in the region, among other risks.

Arms proliferation has been blamed by the population, especially leaders, for undermining traditional governance, social systems, and the rule of law. Gun ownership has sadly become a status symbol for a significant proportion of the population, particularly the youth, and this trend is undermining the status quo of traditional leadership, native administration, and the rule of law.[2] Due to the long-running conflict, a violent culture has developed alongside this. People use firearms to settle inter-communal disputes, mainly prompted by competition over land, water, and mineral resources. Given the above, leaders and communities have yearned for local actions to reduce SALW in the past and still continue to do so.[3]

The Doha Document for Peace in Darfur (DDPD) included provisions for civilian arms control, according to which the parties to the agreement, including the GoS, were to prepare a strategy and plans for implementing a voluntary civilian arms control programme with the UN Development Programme (UNDP) and UNAMID’s assistance.[4] However, despite UNAMID’s numerous offers of assistance to the GoS, no such strategy or plans were developed.

Progress Against Arms Proliferation and Conflict

In May 2012, at a meeting of ministers responsible for internal security from Sudan, Chad, Libya, and the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), the Khartoum Declaration on “The Control of Small Arms and Light Weapons across the bordering countries of Western Sudan” was announced.[5] Following this Declaration, the Sudan Disarmament, Demobilization, and Reintegration Commission (SDDRC) and Bonn International Centre for Conversion (BICC) initiated a trial arms registration and marking (ARM) operation in West Darfur in March 2013, with the ultimate aim of determining the number of firearms in circulation in Darfur. A total of 2 000 guns were marked, mainly AK47s from the Sudan Police Forces (SPF). After registration, the weapons were immediately returned to their owners because the goal was not to seize them.

In 2014, UNAMID developed a Mission Strategy for SALW control activities in consultation with UNAMID components, namely, the military, police, civilians, UN Country Team (UNCT), and key national and international actors. This was in light of the increasing proliferation of SALW in Darfur, UNAMID’s protection of civilians (PoC) mandate, increased attention from the UN Secretary-General and UN Security Council on SALW, and emphasis on civilian protection.[6] The plan was developed after a study of the UN, GoS, and other actors’ ongoing SALW control operations to ensure that UNAMID interventions complement and support existing activities, while also filling any gaps in intervention.[7]

With the UNAMID mandate and goal of protecting civilians through activities to strengthen SALW control, the Mission donated five gun-marking machines in March 2016 to the SDDRC, trained 20 technicians to operate the machines, and provided 500 gun lockers (with the possibility of providing additional lockers, depending on progress) as an incentive for those willing to mark and register their weapons. The initiative, however, failed for reasons outside of the Mission’s control. This is because, contrary to the goal of marking illegal civilian guns, the operation labelled 2 000 weapons, mostly SPF weapons. Travel restrictions and other factors, including disagreements between BICC and the Sudan DDR Commission regarding how to move forward with the pilot, led to BICC withdrawing their support, which contributed to the initiative’s failure.

Without a national normative framework or sufficient public awareness, the GoS officially began the weapons-collecting drive in Darfur in July 2017. The initial part of the campaign received widespread praise and support from the Darfuri people, but the operation ended a few months later for unexplained reasons. Despite the relative peace and security that many people in different sections of the region experienced, competition for the few natural resources available and the proliferation of firearms continued to be the main causes of violence. The GoS weapons-gathering drive received a mixed response from the public because of the continued violence. The general population, especially people of African descent, and civil society have criticised it for being biased and having a narrow scope and coverage.

Many Darfuris believe that the continued possession of firearms by nomadic herders and militias has made it difficult for refugees and IDPs to return. For those who have, the security situation was unsuitable for their continued stay. Consequently, the affected displaced persons have chosen to return only seasonally to work their farms due to the unstable security situation. According to field reports, new waves of proliferation were observed during the 2018–19 uprising and after the collapse of the former National Congress Party (NCP).[8]

Lastly, it is important to note that in the aftermath of a destructive and protracted conflict, the consequent breakdown of law and order and the absence of the rule of law, civilian disarmament is difficult, especially if residents lack confidence in the government and state security institutions’ ability to protect them. Furthermore, the fact that certain social groups own weapons as part of their cultural and customary practice adds another layer of complications. These factors affect how willingly people will surrender their firearms. To establish the appropriate type of intervention, a thorough investigation of the purpose of weapons possession and an assessment of the quantity and types of weapons in use is necessary.

The Pilot Community Security and Arms Control Projects

UNAMID had no explicit mandate for civilian disarmament. The role assigned to UNAMID in the Doha Document for Peace in Darfur (chapter IV, article 66) was a collaboration with UNDP to help the GoS develop a national normative framework for arms collection.[9]

It is crucial to clarify that, despite some similarities, “civilian disarmament” and “disarmament, demobilization, and reintegration (DDR)” are very different operations. Combatants of armed movements that have ratified peace accords are the focus of DDR programmes. On the other hand, “civilian disarmament” describes the removal of weapons and ammunition from civilians, and most often, this is accomplished through voluntary surrender, which is driven by the desire to prevent eventual seizure and prosecution. Positive inducements are also frequently provided, such as incentives for tools, livelihood initiatives, certificates of appreciation, or money. However, in the Darfur region, the militias are intricately intertwined with the respective ethnic groups from which combatants are recruited; therefore, it is difficult to distinguish between civilians and militants.

The pilot CSAC projects were prompted by the highly divisive and compulsory civilian disarmament in 2017, which abruptly ended several months later, and the plans of the GoS High Committee on National Arms Collection Campaign to implement yet another mandatory arms collection campaign in 2020. This campaign was specifically to focus on IDP camps, where residents are typically perceived by the GoS as supporters of rebel movements.

The Office of the Wali Governor decided to initiate the pilot projects in the West Jebel Marra and Azoum localities based on the high levels of gun violence and insecurity in those areas, although there was no official baseline information to provide an indication of the number, type and distribution of guns in circulation. However, the Mission’s field reports also indicated that the West Jebel Marra locality was notorious for gun violence between farmers and herders over grazing lands, between IDPs and Arab militias, and for livestock rustling. In the Azoum locality, gun violence is mainly intercommunal and between and within IDP camps, aligned with different rebel movements and cattle rustling. These crimes were further exacerbated because of the lack of state authority, law and order, and the culture of impunity.

The primary objectives of the projects were to:

- Trial an inclusive and rights-based approach to civilian disarmament in the aftermath of the government’s widely criticised civilian arms collection campaign, which started in 2017 and abruptly ended after a few months; and

- Identify lessons learnt to help the government develop a national civilian disarmament policy that aligns with international standards and guides future arms collection campaigns.

Given the above, UNAMID initiated the pilot projects to identify innovative and creative approaches to address the proliferation of weapons in Darfur based on its mandate for the PoC, to draw lessons to guide future interventions, and to recommend best practices to the government to guide its planned national arms collection campaign. A successful CSAC can support more extensive political and peace-building processes, reduce the likelihood that individuals or groups will participate in violent behaviour and conflict, prevent accidents, and save lives by addressing the immediate dangers of illegal weapons possession.

The pilot projects were developed by the Mission in conjunction with the SDDRC and later discussed with the Office of the Wali Governor to gain political support at the highest level in the State and in the localities where the projects will be implemented. Additionally, as disarmament is a politically sensitive and highly technical undertaking, coordination and broad involvement of diverse sectors are required to gain political and popular support and acquire local and international expertise.

Moreover, as part of the implementation strategy for the projects, community mobilisation and sensitisation meetings were held to promote local ownership and support, explain the benefit structure and community roles, and discuss the procedure for appointing members of the PMCs to manage the projects. The PMC was constituted and comprised nine members to increase involvement and strengthen support. They included members of the locality commissions, native administration, local security committees, nomadic herders, agricultural protection committees, peaceful coexistence committees, youth and women’s organisations, and influential residents. In addition to their administrative duties, the members acted as points of contact between the PMC and their respective institutions to facilitate project implementation and deal with any problems that could arise.

Public and strategic information was conducted at both the state level and in project communities to mobilise political and popular public support for the projects. At the state level, radio commercials, regular radio shows, and phone-in programmes were used to promote participation through electronic media for wider geographic coverage. Jingles and advertisements using loudspeakers, spanning numerous communities, including nomads, posters, and banners placed in public locations, were employed to increase the community’s knowledge of and support for the effort. To reach as many people as possible, drama productions (short skits) highlighting the hazards of illegal gun ownership were performed in major towns and villages, notably on market days. Moreover, to promote community understanding and support for the projects, community meetings were organised and sporting events were planned.

The SPF and the UN Ordnance Disposal Office (UNODO) led the technical aspects of the project. The UNODO specifically led the construction of shipping containers for weapons storage, while the SPF led the collection, handling and storage of the weapons collected in line with their expertise and duty. Youths participated in drama productions and public information dissemination through announcements made over loudspeakers, jingles, and the exhibition of posters and banners. Women attended community meetings and other public meetings, as well as participating in the short plays. Both youths and women participated in the PMCs and provided coordination roles. Traditional authorities served as custodians of project inputs and materials, served as members of PMCs, and helped resolve implementation challenges. Farmers and herders helped awareness-raising efforts in their communities and facilitated the surrender of weapons.

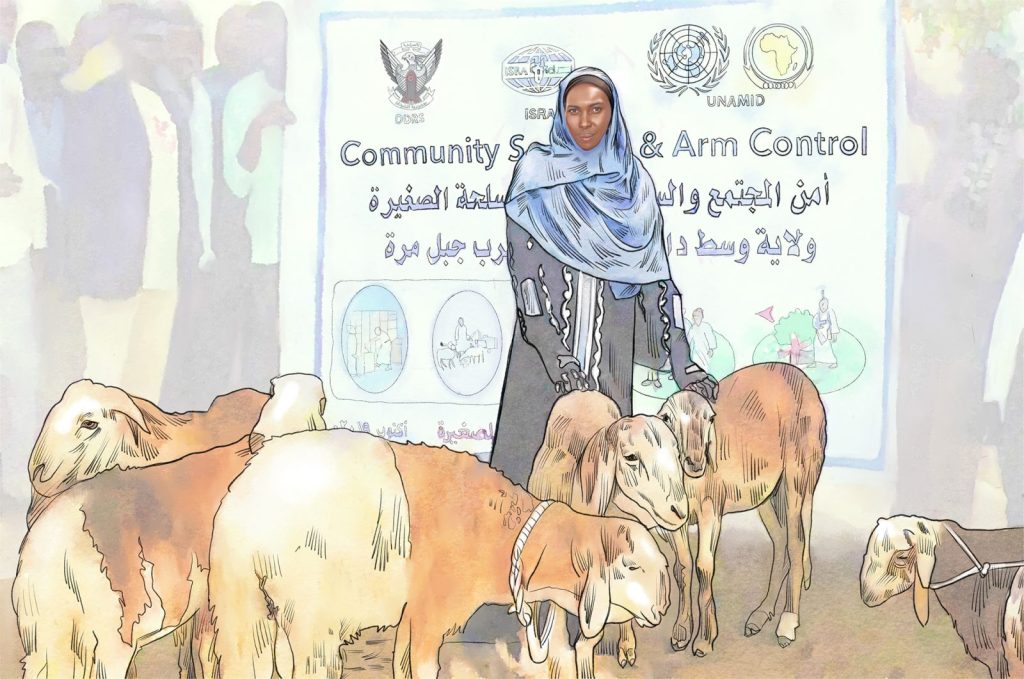

An NGO implementing partner, the Islamic Relief Agency (IsRA), implemented the projects, which were completed in May 2020, targeting 529 000 people in both localities. They collected 200 firearms in total, 100 from each locality, in exchange for various alternative livelihood opportunities.[10] For the secure storage of weapons and ammunition, the project also built and installed two armouries, using sea containers at each project location.

The application of a comprehensive strategy included livelihood support for voluntarily turning in guns and general support for safer management of civilian firearms and ammunition. Those who voluntarily turned in their firearms received training in livelihoods, small business start-ups, and income-generating activities. They were also given incentives, such as agricultural inputs like water pumps, seeds and fertilisers; livestock like sheep, goats and cows; assorted goods like sugar, oil and tea for grocery stores; and traditional salt for animals, among other items, to support their families through peaceful means, rather than using weapons and engaging in banditry or other criminal activities.

Overall, the communities received the pilot CSAC projects positively because they saw the initiatives as a step in the right direction toward reducing crime, violence, and unrestricted access to firearms in their communities. More people with guns were willing to participate in the project, but their numbers were greater than what the project could accommodate. This is because the projects heavily invested in risk communication and community awareness of the dangers of illegitimately possessing firearms; promoted the idea of safe storage of firearms and ammunition to prevent their unintentional use by children; and promoted the message of peace through a return to normal life and engaging in income-generating activities, such as agriculture and livestock among other things. The projects also demonstrated an example of how the Mission, civil society, State authorities, the SPF, community leaders, women, youths, farmers, and herders could work together to achieve politically sensitive goals.

Key Lessons

The pilot CSAC projects revealed many noteworthy insights and lessons that could be used in future Darfur-based and worldwide programmes, as described below.

Baseline Data

For any project, baseline data is essential for determining the scope and comparing the existing situation before and after the project, as well as its impact on the community. It was impossible to estimate how many firearms remained in the communities following the project. Therefore, baseline information is required for future arms control interventions to determine the scope of intervention, how many guns are still in circulation, and how they impact the security and stability of the communities.

Network of Inclusive Partnerships

UNAMID and its NGO partner were successful in promoting both local and political support for the project by fostering cooperation among national and local organisations, including the Sudanese security forces and institutions, civil society, traditional authorities, highly influential individuals, IDPs, and refugees, among others. As a result, it was possible to apply a bottom-up strategy and make efficient use of local resources and expertise, for example, the SPF, local leadership, and early intervention to address implementation problems and complete the projects on schedule.

Project Management Committees (PMCs)

An inclusive PMC was established to facilitate implementation, coordinate project activities, and provide guidance and general support to implementation for a greater sense of local ownership and sustainability. The PMCs helped mobilise community support, facilitate sensitisation and awareness-raising initiatives, and ensure the prompt resolution of issues and timely completion of projects because of their local knowledge and social connections. The PMCs are crucial for the project’s continued viability.

Political Will and Popular Support

Strong political will and popular support at the highest levels of government are the two most important prerequisites for an effective campaign to collect SALW. The success of the implementation was directly impacted by the assistance of the Wali Governor’s office and the two Locality Commissioners.

Public Information and Strategic Communication

Arms collection campaigns are politically sensitive undertakings and must be well planned, with public information and strategic communication at the core of their implementation. Communication helped in several ways, including mobilising political and public support, highlighting the dangers of unregulated gun ownership, and managing expectations. These converging factors were necessary for the successful implementation of the projects.

Project Incentives for Voluntary Surrender of Weapons

As a common practice and part of the larger plan, people who voluntarily turned in their firearms were to be provided with either in-kind individualised or group assistance. However, in both project locations, project beneficiaries preferred individualised assistance over group support. The in-kind assistance was calculated based on the then-current market price of firearms to encourage the voluntary surrender of firearms in return for livelihoods. Critics interpreted the exchange of personal livelihood assistance for firearms as a programme to repurchase weapons or as restitution for unlicensed gun ownership.

International Standards for Weapons and Ammunition Management

The study showed that the SPF did not meet the requirements for physical security and stockpile management by following the international standards for managing weapons and ammunition, particularly the International Ammunition Technical Guidelines (IATG) and the Modular Small Arms Implementation Compendium (MOSAIC). It was noted that the firearms gathered were not registered or serial-tagged with the appropriate numbers. It was also observed that the magazines and the serviceable and non-serviceable guns were not maintained separately, but rather kept together in the same place, among other risks.

Recommendations

The implementation of the pilot projects in Darfur has allowed the identification of several key elements and recommendations that may prove helpful in developing future CSAC programmes, as well as long-term community security and stabilisation programmes. These include:

- A weapons survey is an essential prerequisite for any comprehensive civilian disarmament plan. This provides information for developing specialised, secure, and effective arms control measures. A weapons survey involves gathering and reviewing quantitative and qualitative information regarding firearms and ammunition within any given geographic area. Such a survey facilitates the requisite collection, storage, and destruction requirements.

- Establishing PMCs is crucial in leveraging a wide network of partnerships at the federal, state, municipal, and community levels to offer coordination, technical guidance, and direction for implementation. Building a vast network of collaborators – including international partners – is essential to any initiative involving the large-scale collection of weapons since these aspects are crucial to long-term resource mobilisation and transparency. Additionally, stakeholders must plan a participatory and inclusive consultative conference to discuss past experiences and initiatives undertaken by various national and international actors to develop a national strategy for arms control in Darfur.

- Darfur-wide support is required for a comprehensive arms collection programme. It must involve thorough public education and a strategic communication plan to increase civilian support for fostering national and local ownership. Besides, the communication strategy helps clarify the scope of the projects, manage community expectations, and raise awareness of the dangers of illicit and uncontrolled possession of firearms.

- Although incentives for the voluntary surrender of weapons are not required, it is a frequent practice to encourage civilians to hand over their guns. It is also crucial to minimise negative views on individual or group incentives for those who voluntarily surrender their firearms. To create trust and confidence in any small arms control programme, community development should be a foundational element for similar efforts in the future.

- Effective SALW control requires effective weapons and ammunition stockpile management with a “whole-life management” approach. Therefore, there is a need for qualified personnel for the technical aspects, inter alia, categorisation, accounting, and physical security. This means that for large-scale civilian disarmament, there is a need to provide training for all personnel involved in weapons handling and storage.

- A national normative framework or strategy is required to direct and inform a significant SALW control and management programme in Sudan due to the proliferation of SALW in regions such as Darfur. This framework would also allow the government to reserve money through its annual budgetary procedures to deal with weapons proliferation on its own or to support international efforts to address the ongoing dangers of proliferation in post-conflict countries. Furthermore, it could be used as a resource mobilisation tool to support the government’s arms control efforts.

Conclusion

Civilian disarmament is frequently a highly divisive and politically sensitive undertaking, particularly in countries where law and order have broken down because of protracted conflict or where some populations have a gun culture. Therefore, any effort to collect weapons must have the backing of the highest levels of government and the general population. All efforts to reduce the use of guns should be carefully thought out, inclusive, compliant with international standards, and guided by a national strategy and comprehensive public information and communications plan to mobilise political and public support. Finally, governments must work to address the underlying reasons for illegal arms possession in settings, especially in contexts characterised by insecurity, a lack of the rule of law, and impunity.

Endnotes

[1] The Arab Weekly (2020) ‘Sudan destroys thousands of firearms in disarmament campaign’, 30 September, Available at: <https://thearabweekly.com/sudan-destroys-thousands-firearms-disarmament-campaign> [Accessed 6 September 2022].

[2] UNAMID (2013) 2013-2019 Developing Darfur: A Recovery & Reconstruction Strategy, Available at: <https://www.humanitarianresponse.info/sites/www.humanitarianresponse.info/files/documents/files/final_english_dds_13.8.13.pdf> [Accessed 6 September 2022].

[3] Ibid.

[4] UNAMID (2015) Doha Document for Peace in Darfur, Available at: <https://unamid.unmissions.org/doha-document-peace-darfur> [Accessed 6 September 2022].

[5] AU (2012) 2012 Khartoum Declaration, AU Conference of Ministers in Charge of Communication and Information Technologies, Khartoum, Sudan, 2-6 September, Available at: <https://au.int/sites/default/files/documents/30935-doc-declaration_khartoum_citmc4_eng_final_2.pdf> [Accessed 6 September 2022].

[6] UN Security Council (2014) ‘Special report of the Secretary-General on the review of the African Union-United Nations Hybrid Operation in Darfur’, S/2014/138, Available at: <https://www.ecoi.net/en/file/local/1325000/1226_1394790696_n1424520-darfur.pdf> [Accessed 6 September 2022].

[7] UNODA (n.d.) ‘Small arms and light weapons’, Available at: <https://www.un.org/disarmament/convarms/salw> [Accessed 6 September 2022].

[8] UNAMID (2020) ‘GCSS’, Available at <https://unamid.unmissions.org/gcss> [Accessed 6 September 2022].

[9] UNAMID (2015), op. cit.

[10] Final project narrative and financial report (June 2020).