- Policy & Practice Brief

When values inform approaches to climate security: The case of Zambia’s Southern Province

This policy and practice brief discusses the significance of community values in addressing climate related security risks.

Executive summary

The outcomes of climate-related security risks are also a function of how the values of those affected influence how they perceive and interpret that hazard, in addition to a function of the extent to which a society is economically, politically, and technologically prepared to cope with the damaging consequences of a particular hazard. This policy and practice brief (PPB) discusses the significance of community values in addressing climate-related security risks. Values are understood as what is most important to communities and what is most considered worth preserving and pursuing. Based on fieldwork research in Zambia’s southern province, it concludes that for climate security interventions to be effective and sustainable, local values must be foregrounded because they increase local acceptance of implementation. Knowledge of community values and the extent to which they are affected by climate security risks provides insights into where it hurts the most. Conversely, building interventions around less strongly perceived impacts on values will receive low uptake and gain less traction. Climate security interventions should prioritise a climate-security values assessment to understand the subjective and differential impacts of and responses to climate security risks, as well as the opportunities and barriers to peace and security that arise from the values.

Introduction

The outcomes of climate-related security risks, understood as the ramifications of climate change for patterns of conflict, insecurity, and instability, are a function of the extent to which a society is economically, politically, and technologically prepared to cope with the damaging consequences of a particular hazard. They are also a function of how the values of those affected influence how they perceive and interpret that hazard. Values refer to what is most important to communities and what is most considered worth preserving and pursuing, such as culture, religion, tradition, gender equality, health, safety, harmony, and freedom. They determine how people perceive, interpret, and define risks, thus influencing denial or acceptance of risks and what responses and interventions are good or bad, fair or unfair, legitimate or illegitimate. Individuals’ perception that their values are under threat influences the actions that they might approve of in service of those values.19Hitlin, S., & Piliavin, J.A. (2004). Values: Reviving a Dormant Concept. Review of Sociology, 30, 359–393. If a climate security risk is rated as strongly affecting a specific value, that value becomes a strategic basis for formulating policies, developing intervention strategies, and mobilising community participation because people prioritise what resonates with their values. This makes values important when considering programmatic and policy decisions for climate adaptation, peace and security. However, values have received less attention in climate security and adaptation scholarship.

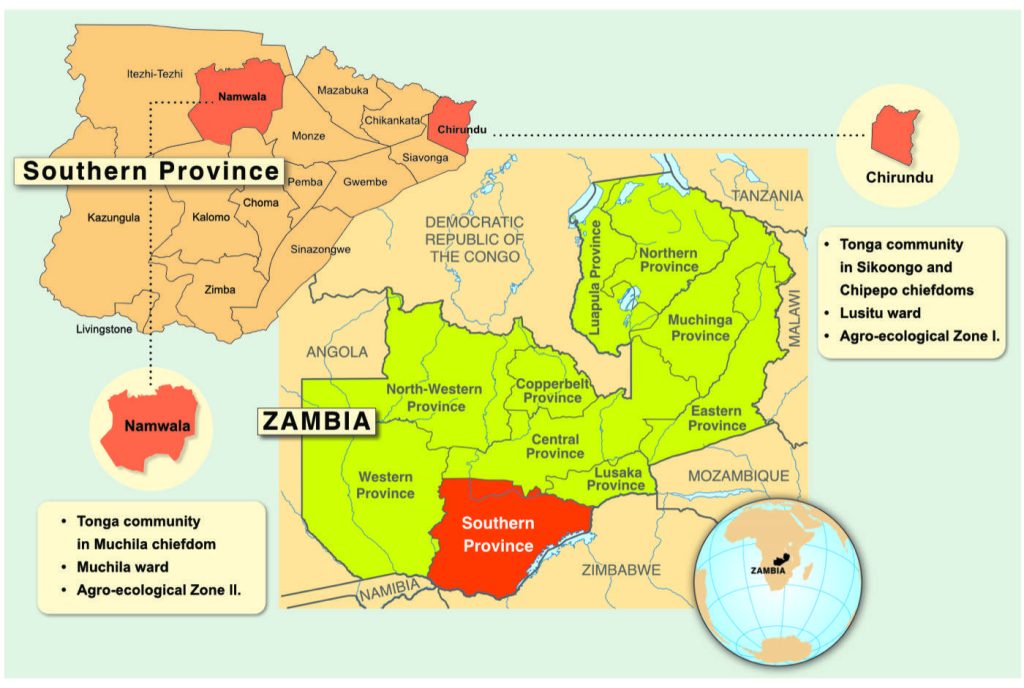

To uncover local communities’ perceptions and experiences of the extent to which climate security risks affect values and shape their understanding of and response to climate insecurities and acceptance or non-acceptance of interventions, the Consultative Group on International Agricultural Research (CGIAR) FOCUS Climate Security team applied a value-based approach in the Muchila and Lusitu communities in Namwala and Chirundu districts respectively, in the southern province of Zambia. The southern province is the most affected by climate change and variability, hence our selection. Climate variability has stifled Zambia’s potential for growth. Since the 1980s, Zambia has suffered droughts resulting in crop failures, livestock decimation and siltation of reservoirs. This has had negative effects on people’s livelihoods, such as crop production and keeping livestock.20Sichingabula, H. M., & Sikazwe, H. (2004) Occurrence and magnitude of hydrological drought in Zambia: Impacts and implication. Hydrological Extremes: Understanding, Predicting, Mitigation. IAHS, 255, 297–305. The changing climate is aggravating the situation, bringing increased frequency and severity of floods and droughts to the country, adversely affecting agricultural productivity, food security, and water resources, among other aspects of the economy and livelihoods, and threatening the lives of thousands of people.

In Namwala district, the Ila people engage mostly in herding cattle, fishing, hunting and subsistence farming.21Kalapula, S.C., & Mweemba, L. (2018) Social-ecological typologies to climate variability among pastoralists in Namwala District – Zambia. World Journal of Sociology and Anthropology, 2(1), 8–24. Livestock is used as a means of production, as sources and objects of labour, as a source of economic value, and as social, cultural and capital goods. Cattle fulfil several social functions, such as in traditional ceremonies and payment of a bride price, in accordance with traditional Ila arrangements. In crop production, cattle provide draught power for ploughing, transport and manure. Cattle are also perceived as the main form of security and a store of wealth.22Ibid. Over the last four decades, Namwala District has experienced climate variability, especially in the form of an increase in the mean annual temperature by 1.2°C and a decrease in mean rainfall of 1.8mm/month. The rainy seasons have become less predictable and shorter. Rainfall now occurs in fewer but more intense events. These extreme weather events are set to increase. The intensity and frequency of droughts and floods have increased, as have the number of people affected. The net trend is towards more floods and, over a longer period, droughts. The areas affected by floods and droughts have also increased. Furthermore, weather shocks and cattle diseases have reduced livestock numbers. These social-ecological typologies have negatively affected the Ila’s socio-economic situation and threatened their food security. Droughts have depleted animal grazing resources and drinking water, thus causing conflicts over grazing land.23Ibid.

Chirundu district is located in the Lusaka province and is characterised by very hot weather, with temperatures reaching about 50°C in summer, and low average annual rainfall of less than 800mm.24Dumenu, W.K., & Takam Tiamgne, X. (2020) Social vulnerability of smallholder farmers to climate change in Zambia: the applicability of social vulnerability index. SN Applied Sciences, 2, 436. The district is semi-arid, and its temperatures tend to be higher than elsewhere in the country. Its main livelihood activities include cereal production, fishing along the main rivers, raising animals and tourism in the parks and lakes located within the region. The district is experiencing direct climate-change effects, such as reductions in and uneven distributions of rainfall, increasing frequency and intensity of droughts, occasional flooding, increasing temperatures and environmental degradation. These effects are already affecting the viability of fishing and farming through the reduced availability of water for crop production, livestock and domestic use.25Ibid.

Research design

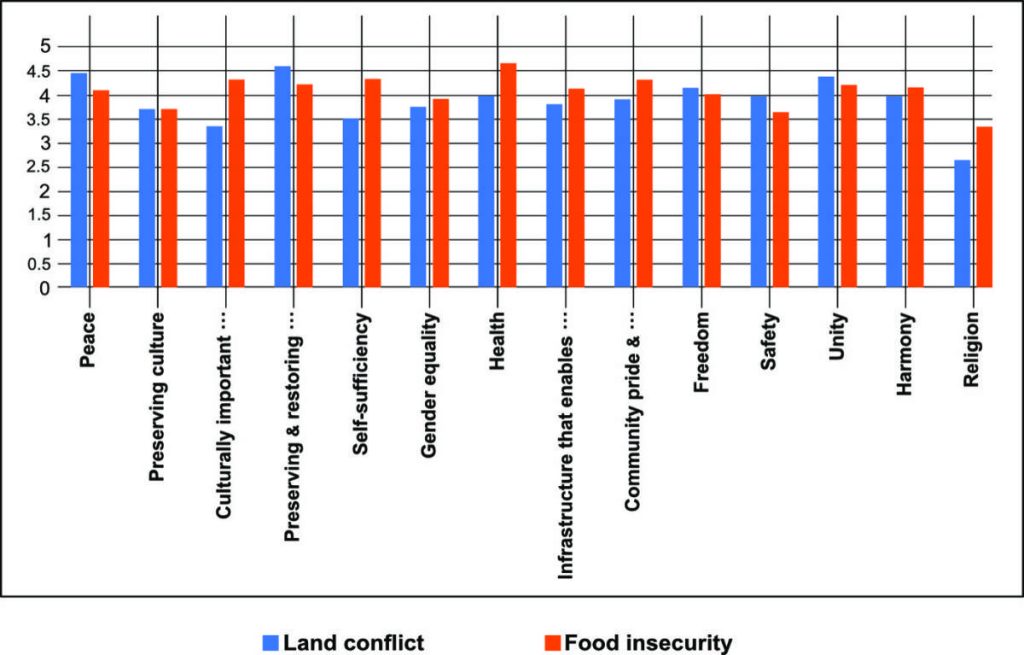

We first identified the values of the two communities regarding family life, social interaction and inclusion, gender, faith, and nature through a literature review and validated them through discussions with the participants during the first and second days of our focus group discussions. The following values were finally under consideration: peace, preserving culture, preserving culturally important foodstuffs, preserving and restoring the environment, self-sufficiency, gender equality, health, infrastructure that enables us to live well, community pride and cooperation, freedom, safety, unity, harmony and religion. The participants then completed a survey to rank the extent to which the two most significant risks in the province, land conflicts and food insecurity, were affecting their values. Women and men completed the survey separately to ensure that the women felt free to complete the exercise. Twelve women and twelve men comprising village heads, women group leaders, and young people participated. We processed and analysed the survey data using SPSS software.26We would like to thank Anja Visser for helping with the design of the survey and setting up the software for analysis. We also want to thank Marisa O. Ensor for her research assistance with the women’s group. A higher rating indicated the centrality and salience of values in the climate security discourse. A lower rating would have the opposite meaning to this. If climate-induced conflicts over land are rated as strongly affecting culture as a value, culture becomes a strategic basis around which to organise responses and mobilise local participation because people are prioritising what is congruent with their values.27Perlaviciute, G., & Steg, L. (2015) The influence of values on evaluations of energy alternatives. Renewable Energy, 77, 259–267. <https://doi.org/10.1016/j.renene.2014.12.020> This would also mean that any intervention strategies to address the risks that would undermine their culture would have a low acceptance. In fact, they may exacerbate the risk or initiate a new one.

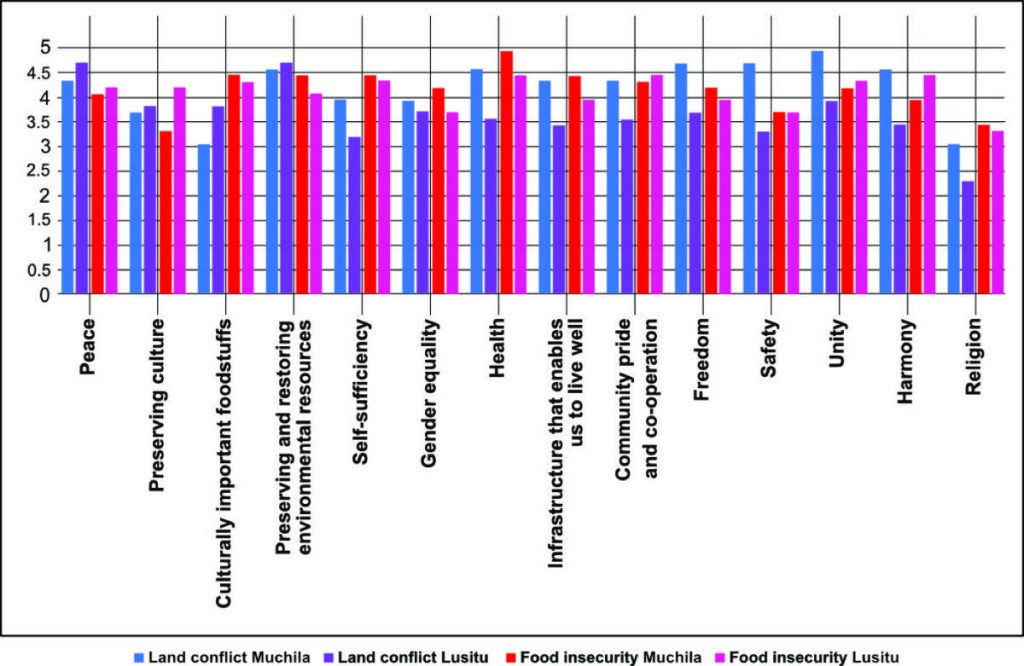

Figure 2 shows that, on average, the participants perceive both land conflicts and food insecurity as having a strong to very strong impact on their values (scores between 3 and 4.6 on a scale of 1 (lowest) to 5 (highest)). Ranking the impact between strong and very strong with relatively small margins of difference shows that the impact of climate security risks on the different communities’ values is not a matter of speculation but a reality where intervention is required, values being central for transformational and fundamental interventions.

When comparing the impacts of land conflicts and food insecurity on the various values, the participants feel that all values except religion are impacted similarly. The participants perceive the effect of land conflicts on religion (2.63) to be significantly less than the effect on unity, peace, and preserving and restoring environmental resources (4.37, 4.44, and 4.56, respectively). For food insecurity, the perceived effect on religion (3.31) was significantly less than on health (4.62). Overall, equally strong impacts of land conflicts and food insecurity were perceived. What was felt to be a low effect on religion compared to other values may confirm a strong belief in God as omnipotent and thus too powerful to be affected by any risks. This belief may lead to inaction and a policy of leaving everything to God. Here, religion specifically refers to the different denominations of Christianity, such as Seventh-Day Adventist, Roman Catholic, Methodist, and Pentecostal, among others. Indigenous religions were perceived as part of the culture. It might also be that the low impact on religion – as faith rather than as a cultural expression – may be linked to it having an individual dimension as well as a social value, whereas unity and peace are mainly social values. Traditional ceremonies were considered a part of both culture and indigenous religions. Key ceremonies in the southern province include the Shimunenga, where:

- cattle are herded past a ceremonial ground so that Shimunenga, a great warrior who lived about 400 years ago, successfully led the Ba Ila against marauders, and is buried in a sacred ground outside the village of Maala, may look kindly on them and protect them against pestilence in the coming year.28Namwala Cultural and Traditional Trust. (2017) The Ba Ila. Available from: <https://www.namwalatrust.org/culture> [accessed 15 July 2023].

- Iwiindi is held when people are preparing their fields. The belief is that without the blessings of their ancestors, the fertility of the land, and hence productivity, is compromised. The chief is thus obliged to supplicate the ancestors for good rains and harvests.29Kaoma, K. (2017) Towards an African theological ethic of earth care: Encountering the Tonga lwiindi of Simaamba of Zambia in the face of the ecological crisis. HTS Teologiese Studies/Theological Studies, 73(3), a3834. <https://doi.org/10.4102/hts.v73i3.3834> Thus, the participants perceive the impact of food security and land conflicts on preserving cultural and culturally important foodstuffs to be significantly stronger than on religion. The impact could also strengthen and reinforce the importance of the value of culture as, in times of food insecurity, cattle and the fertility of the land become even more crucial.

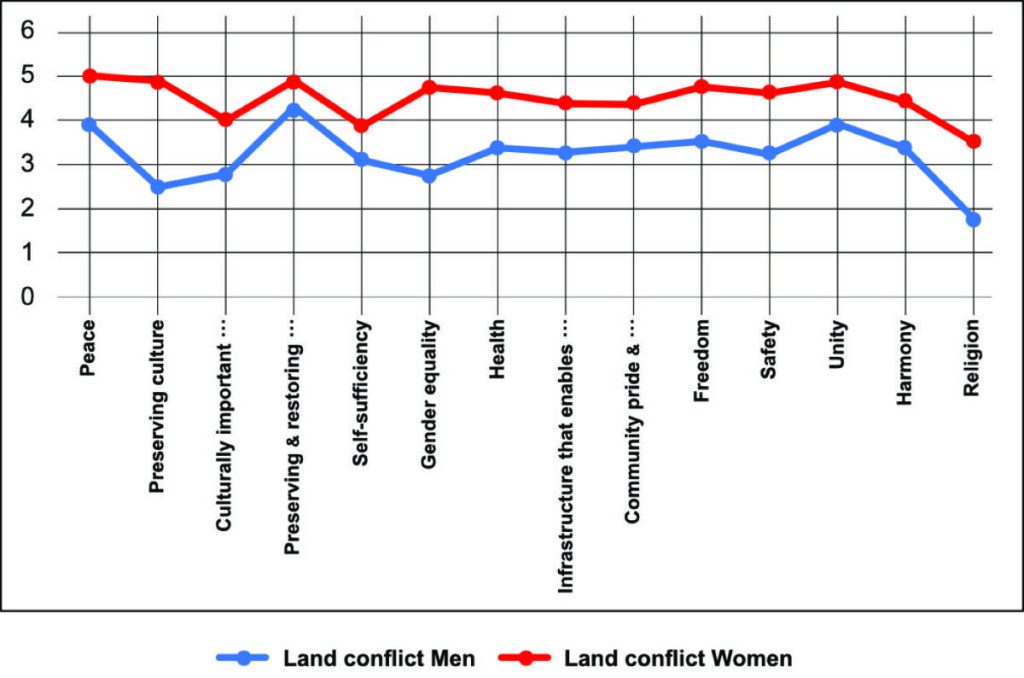

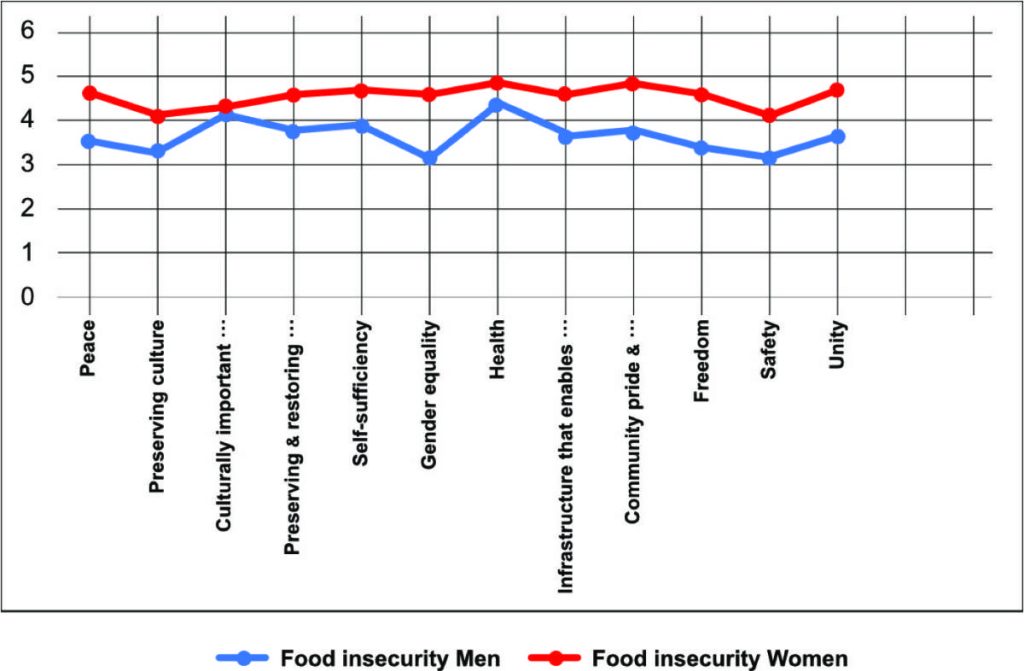

Looking more closely, women perceive the impact of land conflicts and food insecurity significantly more strongly than men (see Figures 3 and 4).

Women perceived the impact of land conflicts on peace, preserving culture, gender equality, health, community pride and cooperation, freedom, safety, and religion to be significantly stronger than men.

Women also perceived the impact of food insecurity on peace, self-sufficiency, gender equality, infrastructure, community pride and cooperation, freedom, unity, harmony, and religion to be significantly stronger than men. It is significant that women from both communities ranked the impact of land conflicts and food insecurity higher than men. This finding confirms that women are more affected by climate-related security risks than men.30Mwaba, B. (2023) Impact of Climate Change in Zambia: Women Confronting Loss and Damage in Zambia. LinkedIn. Available from: <https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/impact-climate-change-zambia-women> [accessed 23 July 2023]. This can be attributed to cultural norms of gender roles, which designate women as the primary caregivers and providers of food and fuel in their households. In the context of climate change and the consequent resource scarcity, these responsibilities become more difficult to perform. It could also mean that, in their role as primary caregivers, they worry more about the impact and perceive the links to be stronger.

However, when comparing the impacts of land conflict and food insecurity with each other, only one gender difference was found: women perceive preserving culture to be slightly more impacted by land conflicts than by food insecurity, whereas men perceive this value to be slightly more impacted by food insecurity than by land conflicts. This is a somewhat unexpected finding because one would expect the women to be more concerned about the effect of food security than land conflicts, given that they are closer to food provision and not immediately involved in these conflicts as they do not have rights over land. It might be that they are more concerned about the source of food because, in these communities, land means food, and food and land are culturally regulated. It might also be that peace and collaboration are critical values for women. During the focus group discussions, women expressed that climate change impacts were affecting community solidarity and collaboration. Land conflicts would, therefore, be perceived to be more strongly impactful than food security. Customary tenure covers 93% of the Zambian area and is controlled by the chiefs and their headmen.31Van Loenen, B. (2000) Land Tenure in Zambia. University of Maine. Available from: <https://api.semanticscholar.org/CorpusID:10587491> [accessed 30 July 2023]. Thus, land conflicts affect food security, which is the responsibility of the women according to their culture. This also reveals that conflicts that do not involve women directly still affect them significantly.

Only one difference was found between the two communities: people in Muchila perceive the impact of land conflicts on safety to be stronger than people in Lusitu (4.63 compared to 3.25; see Figure 5).

This finding is understandable because, in Namwala district, where the Muchila community lies, cattle are central to the rural economy and play an important role in the people’s livelihoods. Consequently, cattle need land for grazing, and conflicts over land32The Daily Nation. (2018) Namwala Saga. Available from: <https://www.pressreader.com/zambia/daily-nation-newspaper/20180416/281586651185929> [accessed 15 July 2023]. revolve mostly around grazing land. Furthermore, more than 70% of the population in Namwala is dependent on crop cultivation. Due to the shortage of grazing land, cattle encroach onto land reserved for crop cultivation, sometimes destroying agricultural crops in search of food. In the final analysis, land is one of the most important resources available to small-scale rural farmers in Namwala.33Kalapula, S. C. (2013) Socio-economic transformation among traditional cattle keepers in Kafue flood plain in Namwala District, Zambia. Available from: <http://dspace.unza.zm/bitstream/handle/123456789/2086/Main%20Document.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y> [accessed 15 July 2023]. Thus, this could be why land conflicts were perceived to have a stronger impact on safety by the people of Muchila than by those of Lusitu.

Reflections

The above findings demonstrate that land conflicts and food insecurity are perceived to impact strongly on existing values, a perception, in turn, that shapes the responses to the risks by the communities themselves and intervening organisations. Values are thus an important factor in shaping responses to climate security risks because they stem from what matters to different social groups. By using a value-based approach, we can be more certain about specific interests, concerns, and what must be avoided. Interventions can gain acceptance and legitimacy if framed as advancing or protecting the values most strongly perceived to be impacted. Building interventions around values that are not felt to be strongly affected by the identified risks will receive low uptake and gain less traction. Furthermore, knowledge of the values that are perceived to be impacted helps avoid interventions that may exacerbate already-existing conflicts, risks, and gendered vulnerabilities. Interventions thus can elicit conflictual or peaceful responses, depending on the value(s) involved, the people affected, the scale of the effects, and the sensitivity of the interventions to the community’s values. Hence, a context-specific and adaptive34de Coning, C. (2017) Adaptive peacebuilding. International Affairs, 94(2), 301–317. <https://doi.org/10.1093/ia/iix251> approach to peace is required.

A gendered analysis of the impact of climate-related security risks on values has shown that men and women do not perceive, interpret, or define threats to the same values in the same way. Women’s rankings in the survey more often ranged from a strong to a very strong perception of the impact across all values than men’s. This difference can be attributed to women’s culturally and religiously defined roles, like fetching water, firewood and providing food, which are mostly impacted by climate change, inequalities and power relations. Likewise, in different communities, some types of climate-related security risks are more impactful than others based on the community’s history, source of livelihood, culture and religious values. Land conflicts, for example, have more impact than food insecurity in Muchila than in Lusitu. Violating what people hold most dear can lead to intense and intractable conflicts, meaning that values become abstract factors. The ongoing tensions between Chiefs Chipepo and Sikongo,35Lusaka Sun. (2018) Sikongo/Chipepo Chiefdoms wrangle, a Source of Concern. Available from: <https://www.thezambiansun.news/2019/04/28/sikongo-chipepo-chiefdoms-wrangle-a-source-of-concern> [accessed 20 July 2023]. based on the displacement of Chief Chipepo’s community during the construction of the Kariba dam in 1955 and further worsened by climate change, bear witness to this. About 6 000 people were relocated from the Kariba Reservoir basin to the Lusitu region. The Lusitu area, however, was entirely under Chief Sikongo. The Colonial Administration had to ‘obtain’ Chief Sikongo’s ‘permission before the 6 000 Chipepo people could arrive’ – not just to live permanently within his chieftaincy but also to remain under the authority of their own Chief Chipepo. Although permission was given, future conflicts and lawsuits between the hosts and those who had been relocated could be anticipated and, in fact, have occurred.36Scudder, T. (2019) 1956–1973: I Believe Large Dams Provide an Exceptional Opportunity for Integrated River Basin Development. In: Large Dams. Water Resources Development and Management. Singapore: Springer (pp. 27–96). <https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-13-2550-2_2>

Implications for Programming

Based on the above discussion, we make the following recommendations:

Firstly, for interventions to be sustainable, local values must be foregrounded because they increase local acceptance of implementation. Knowledge of community values and the extent to which they are affected by climate security risks provides insights into where it hurts the most. Currently, a focus only on economic and technological explanations and solutions is an obstacle to indigenous people’s participation in climate policy-making or other climate interventions organised and conducted by stakeholders. In this case, interventions in land conflicts and food insecurity can gain acceptance and legitimacy if they are developed and framed around the values that are most strongly perceived to be impacted, such as culture, peace, and health, to mention a few. Conversely, building interventions around less strongly perceived impacts on values, such as religion, understood as different forms of Christianity, will receive low uptake and gain

less traction.

Secondly, interventions must prioritise knowledge of local values perceived as strongly impacted to avoid violation of cultural values and interventions that may exacerbate existing conflicts or risks or initiate new ones. For example, if land conflicts and food insecurity are experienced as strongly impacting the preservation of culture or culturally important foodstuffs, interventions that undermine cultural foodstuffs or cultural practices will only increase existing security risks.

Thirdly, in contexts of multiple climate security risks, a value-based approach will provide guidance on which risk to prioritise. Policymakers and development practitioners should focus their efforts and resources on the most critical areas. To this end, they must engage with what matters most to the affected communities to understand the level of intensity and persistence and which risks should be prioritised during the intervention based on their impact on cultural values. For example, identifying what women value can provide the basis for framing intervention strategies, developing intentional interventions, gaining legitimacy, and increasing their participation in intervention programmes. In this research, women perceived the impact of land conflicts on peace, preserving culture, gender equality, health, community pride and cooperation, freedom, safety, and religion to be significantly stronger than men. Sustainable policies and interventions that promote what matters most for women should thus be developed around these values.

Fourthly, climate security interventions should prioritise a climate-security values assessment to understand the subjective and differential impacts of and responses to climate security risks, as well as the opportunities and barriers to peace and security that arise from the values. As we have seen, women and men perceive the impacts of climate security risks differently, meaning they are affected more and differently. A climate-security values assessment will facilitate the development of gender-sensitive, intersectional, effective, transformative, legitimate, acceptable, relevant and sustainable policies through adaptive programming that focuses on subjective dimensions about what should be protected and what can be tolerated as acceptable outcomes. A climate-security values assessment guards against formulating gender-blind and non-intersectional policies and avoids imposing explanations and solutions from other contexts on local communities.

Fifthly, policymakers and development practitioners should invest time in understanding community values for a solid basis to respond to climate security risks. Interventions that contradict or are perceived to be a threat to what communities consider important and valuable will have a low uptake, be resisted, and lead to ineffective and unsustainable efforts. For instance, solving land conflicts by dividing and redistributing ancestral land will contradict the value of culture and community pride and hence will not gain traction and legitimacy. This is evident from the land conflicts between the Chipepo and Sikongo kingdoms in the southern province of Zambia. Values should, therefore, provide the basis for the time and effort spent considering programmes and policies, thus driving intervention strategies. Introducing a values-based approach in the climate security discourse radically changes the understanding and design of urgently needed intervention strategies for climate-related

security risks.

Authors

Joram Tarusarira is a climate security research associate at the Alliance of Bioversity International and the International Center for Tropical Agriculture (CIAT), one of the research institutes at CGIAR, and an assistant professor at the University of Groningen in the Netherlands.

Giulia Caroli is a climate, peace and security specialist at the Alliance of Bioversity International and CIAT, one of the research institutes at CGIAR.

Leonardo Medina is an environmental peacebuilding specialist currently completing his PhD under the Leibniz Centre for Agricultural Landscape Research.

Gracsious Maviza is a gender, migration and climate security scientist at the Alliance of Bioversity International and CIAT, one of the research institutes at CGIAR.

Acknowledgement: This work was carried out with support from the CGIAR Initiative on Climate Resilience, ClimBeR, and the CGIAR Initiative on Fragility, Conflict, and Migration. We would like to thank all funders who supported this research through their contributions to the CGIAR Trust Fund: https://www.cgiar.org/funders/