Abstract

The question of land has increasingly become a major source of conflicts in many parts of Africa. In Nigeria, claims of rights over landholdings and justice administration of land disputes, though of great concern, have received inadequate attention in the literature. In this context, this paper examines Nozickian distributive justice vis-à-vis land-related conflicts in the Panda Development Area (PDA), Nasarawa state, Nigeria. It focuses on perennial delays-cum-unfavourable rectification of unjust landholdings as drivers of conflict in the area. The study employs the survey method of data collection using key-informant interviews. It adopts a qualitative descriptive method to analyse the data. The paper found that over 80% of the population in the study area rely on agriculture, and that there are numerous contestations over land use and ownership. Unfortunately, still, adjudication of these cases lingers unnecessarily, resulting in distrust, antagonisms and violent confrontations. The study recommends fundamental reform of Nigeria’s justice system as it relates to land matters to ensure more equitable distribution of land. Such reform should include the introduction of special courts as well as the mainstreaming of traditional institutions, local and ad-hoc arbitrators into the dispute resolution mechanisms of land-related cases.

1. Introduction

Land resources (notably gold, crude oil, ore, uranium, iron, marble, barites, columbite, granite) are major sources of income and livelihood for most citizens in agrarian societies of Africa. Over the years, contestation over landholdings has become one of the main sources of social tension and violent conflicts in different parts of the continent, especially Nigeria. Since independence from colonial rule, virtually every country in the continent has experienced different forms of land-related communal conflicts and ethnic wars that could have been avoided. Sadly, multiple state-based and communal-related conflicts have been on the increase in many African states with attendant impacts on lives and livelihoods of the people (Palik et al., 2020). Reports show that 46 state-based and 91 non-state conflicts and wars were recorded in different parts of Africa during 2018–2019 alone. Of the 91 non-state conflicts, 57 were communal conflicts, often related to land and land-based resources (see Palik et al., 2020:1–38).

In Nigeria, incidences of such conflicts have resulted in the current spate of security and development challenges. Communal feuds accounted for the loss of thousands of lives and an unquantifiable number of properties in Nigeria. For example, Adegbami and Adeoye (2021:6–7) report that about 14436 people lost their lives to Boko-Haram onslaughts in a few northern states. In Zanfara state alone, 6319 citizens were killed while about 190340 others were internally displaced between 2011 and 2019 due to armed banditry or localised conflicts. Similarly, up to ₦ 347 million in internally generated revenue and taxes were lost to land-related conflicts in Benue, Kaduna, Nasarawa and Plateau states in 2010 alone (Mercy-Corps, 2016). This estimate does not include various properties lost by individual members of affected areas.

Furthermore, scholars report some of the most notable and destructive localised conflicts, which include, but are not limited to, the 1992 Zango-Kataf crisis in Kaduna state; the Fulani-Tiv clashes since 1998; the Kuteb vs Chamba/Jukun tussle; the seemingly unending Tiv-Jukun skirmishes since 1991–92; the Ife-Modakeke crisis in the southwest between 1981 and 2000; the 2008 Ezillo and Ezza-Ezillo conflict in Ebonyi state; the 2013–2016 violent crises in Wukari local government area(LGA); and the persistent violent clashes between nomadic herdsmen and farmers in north-central and southern parts of the country (Adetula, 2014; Ahon et al., 2021; Ali et al., 2014; Elugbaju, 2018; Oji et al., 2015; Osegbue, 2017; Zachariah and Olisah, 2020).

Whereas the more prominent of these conflicts have received ample media coverage, robust scholarly attention and effective state interventions (Adegbami and Adeoye, 2021; Ali et al., 2014; Elugbaju, 2018; Osegbue, 2017; Otubu, 2015; see Oji et al., 2015; Udoekanem et al., 2014; Zachariah and Olisah, 2020), the simmering feuds prevalent in the Panda Development Area (PDA) of Nasarawa state have been largely under-reported and neglected in research. Moreover, these tensions have received inadequate policy attention. Though they manifest as resource-based conflicts, they are particularly complex land-related disputes that escalate due to unnecessary delays in rectifying cases where land was acquired forcefully, fraudulently by several parties within the community themselves or by indigene-settlers. These conflicts have generally proven to be intractable. The few scholarly interventions, such as Odoemene (2012) and Zachariah and Ngwu (2024) focusing on land-related issues in the area have proven to be too few and far between to aid proper comprehension of the severity, complexity and dynamic nature of the conflicts in the PDA. To bridge this void, this paper highlights the nuances of the conflicts by focusing on the perennial delays and unsatisfactory rectification of landholding disputes as drivers of conflict in the area. This work will be useful in many ways. First, it highlights security implications of the conflicts and specifically identifies the ‘rectification principle’ as outlined in Robert Nozick’s (1974) theory of distributive justice as a useful tool for resolving land-related disputes. Second, it makes practical contributions by offering relevant policy suggestions on how to navigate the contours of such lingering security situations that have placed the lives and livelihoods of a considerable proportion of citizens at risk over an unconscionably prolonged period of time, particularly in the PDA.

2. Theoretical framework

2.1 Distributive justice

This study is anchored on the theoretical assumptions of Robert Nozick’s (1974:149–182) distributive justice, also referred to as entitlement theory of justice. The theory is a derivative of the philosophical assumptions of John Locke, Samuel Pufendorf and Hugo Grotius on property rights. These philosophers held that every individual possesses a suum (sphere of their own), and everybody is sovereign within their own sphere but must not encroach upon the sphere of others. In their view, an infringement on personal or property rights of another person constitutes an injury or injustice to the victim and should be avoided. Moreover, Locke opines that by human reason and by revelation, the earth and its fruits belonged to God, who had given them to the human inhabitants in common to enjoy (Hoffman and Graham, 2009; Mukherjee and Ramaswamy, 2007; Olivecrona, 1974:211–230). For Grotius, “justice consists entirely in abstaining from taking that which belongs to others”, while Pufendorf stressed that “the force of the right of property is such that we are masters over things that belong to us and can prohibit others from using them” (Olivecrona, 1974:212). According to Locke, human beings are naturally in a state of perfect freedom to order their actions and dispose of their possessions as they deem fit and as such, every human being is absolute lord of themselves and their possessions, and no one ought to harm another in their life, health, liberty or possession. Consequently, the political community is entrusted with acting on behalf of injured parties under the direction of the courts and relevant authorities, with the exception of situations where the authority failed to intervene as required (Mukherjee and Ramaswamy, 2007).

Nozick’s (1974) conception of distributive justice mirrors the views of these three libertarian political thinkers. As a starting point, Nozick (1974) conceived of the term “distributive justice” or “distribution” as “the process by which unheld holdings came to be held” [acquired]. According to him, “in a free society, diverse persons control different resources, and new holdings arise out of the voluntary exchanges and actions of persons”. Therefore, what each person gets, they acquire from its original state or “from others who give [to recipient] in exchange for something, or as a gift” (1974:149–150). In his view, such distribution should be based on the fact that the individuals involved are truly entitled to the holdings. Thus, the principle of justice in holdings describes what justice requires about holdings, and this explains why he re-coined the term as entitlement theory of justice (Njoku, 2019). Hence, complete distributive justice implies that “distribution is just, if everyone is entitled to the holdings they possess under a particular distribution in which such holdings were acquired” (Nozick, 1974:153). Further, anyone in possession of or claiming holdings acquired contrary to the principle is indeed committing an injustice, and this should be rectified. Therefore, the holdings of a person are just if they are entitled to them in accordance with the principles of justice in the initial acquisition, transfer or rectification (Nozick, 1974). Nozick cautions that many people misconstrue the term ‘distributive justice’ as a mechanism or criterion to justify sharing or giving out things. On the contrary, it is the principle of justice in the acquisition of holdings.

From the foregoing, three cardinal principles of ‘distribution’ are clear: (a) justice in the original (initial) acquisition of holdings; (b) justice in the transfer of originally held holdings; and (c) rectification of injustice in holdings (Hoffman and Graham, 2009; Njoku, 2019; Nozick, 1974). The first, according to Nozick (1974:174), implies the appropriation of natural resources that no one has owned before—the legitimate “first moves” to acquire something. In this sense, he considers Locke’s ‘proviso’ (theory of acquisition) a means of initial acquisition of holdings. The second principle governs how one might come to own something previously owned by someone else through just means. This process includes voluntary transactions, gifts, inheritance or as demonstrated in the ‘Wilt Chamberlain’ analogy (1974:160–163). Nevertheless, Nozick (1974:150–153) observes:

Not all actual situations are generated through the first two principles, in that some people steal from others, or defraud them, or seizing [sic] their product… Thus, the violations of the first two principles of justice in the distribution of holdings brought about the third principle, which uses historical information about the previous situations of holdings and injustice done in them.

The third principle of rectification has bearing on the proper means of correcting past injustices in acquisition including the unjust transfer or fraudulent claims of holdings. The principle holds that a past injustice in holdings is rectified when its victims are raised to a level of well-being; at least, as high as they would have been, had the injustice never occurred. Consequently, the perpetrators should be obliged by legitimate authority to restore previously held rights or to compensate the rightful owners for any unjust appropriation (Hoffman and Graham, 2009; Nozick, 1974).

The question that arises from the foregoing and that forms the kernel of this paper is: How prompt, favourable or just is the rectification of unjustly held or fraudulently claimed landholdings in the PDA?

3. Historicisation of distribution of landholdings in Nigeria

It is well documented that the land ownership structure and distribution in Nigeria is based on both absolute and derivative interests that evolved through three major epochs: precolonial, colonial and postcolonial periods (see, for example, Udoekanem et al., 2014; Zachariah and Ngwu, 2024). During the precolonial era, the predominant land tenure system in the disparate communities that constituted the area currently called Nigeria was customary land tenancy. Under this system, lands were owned and controlled by members of the community according to their respective customs. Udoekanem et al (2014:182) explain that “during this period, land belonged to the community or a vast family of which many are dead, few are living and countless members yet unborn”. Under this arrangement, land was not the possession of an individual but the property of communities or families, and the individual who worked on or occupied them merely did so in trust of the community or the family.

With the advent of colonialism, however, the precolonial land tenure system was tampered with. Moreover, the entire indigenous sociocultural, economic and political life was truncated and forced to align with the extractive economic motives of the colonial powers. Once they established a foothold, the colonial authorities enacted strict laws and regulations that enabled them to acquire and convey land titles for commercial and governance purposes. Principal among these legislations were the Treaty of Cession (1861), Land Proclamation Ordinance (1900), Land and Native Rights Act (1916), Niger Lands Transfer Act (1916), Public Lands Acquisition Act (1917), Native Lands Acquisition Act (1917), State Lands Act (1918) and Town and Country Planning Act (1947) (Udoekanem et al., 2014; Zachariah and Ngwu, 2024). With this development, the root title of all land mentioned in the Treaty of 1861 was transferred to the British crown and deployed to use according to the preferences of the supervisory colonial authorities in the given area.

At independence (1960), the indigenous successors to the colonial administrations retained — almost intact — the colonial land laws and their absolutist tendencies in the general administration of the country (Kingston and Oke-Chinda, 2016; Udoekanem et al., 2014; Zachariah and Ngwu, 2024). In particular, two principal laws have been enacted since independence to regulate land ownership and control in Nigeria: (a) the Land Tenure Law of Northern Nigeria of 1962 and (b) the Land Use Decree of 1978. In its key essentials, the 1962 legislation retained the key principles of the Land and Native Rights Act of 1916. Specifically, it provided that “all lands in Northern Region in Nigeria whether occupied or unoccupied are ‘native lands’ and are placed under the control [of] and subject to the disposition of the Minister responsible for land matters, who holds and administers them for the use and common benefits of the ‘natives’” (Udoekanem et al., 2014:185).

The 1978 Decree, later christened the 1978 Act, merely repealed the 1962 law and vested all lands within the territory of each state in the federation on the governor of that state to be “held in trust and administered for the use and common benefit of all Nigerians in accordance with the provisions of the Act” (Udoekanem et al., 2014:185). Section 5(1) of the Act empowers the governor of a state to grant statutory right of occupancy to any person for all purposes regarding land, whether or not in an urban area, and issue a certificate of occupancy in evidence of such right of occupancy in accordance with the provisions of Section 9(1) of the Act. This provision has subsisted to date and has been the source of various forms of forceful acquisition and land deprivation by predatory state authorities (Zachariah and Ngwu, 2024:118–148). Additionally, the Act is responsible for much of the confusion and administrative anarchism on land management in the country, leading to fraudulent claims, distrust, litigations and other forms of antagonistic contestation over landholdings (Osegbue, 2017; Otubu, 2015; Udoekanem et al., 2014; Zachariah and Ngwu, 2024). This is hardly surprising, considering Grotius’ assertion that “if a farmer is deprived of the soil which he and his forefathers have cultivated for generations, he will feel it as a severe amputation” (Olivecrona, 1974:215), against which victims would naturally react in defending their rights.

4. Methodology

4.1 Research design

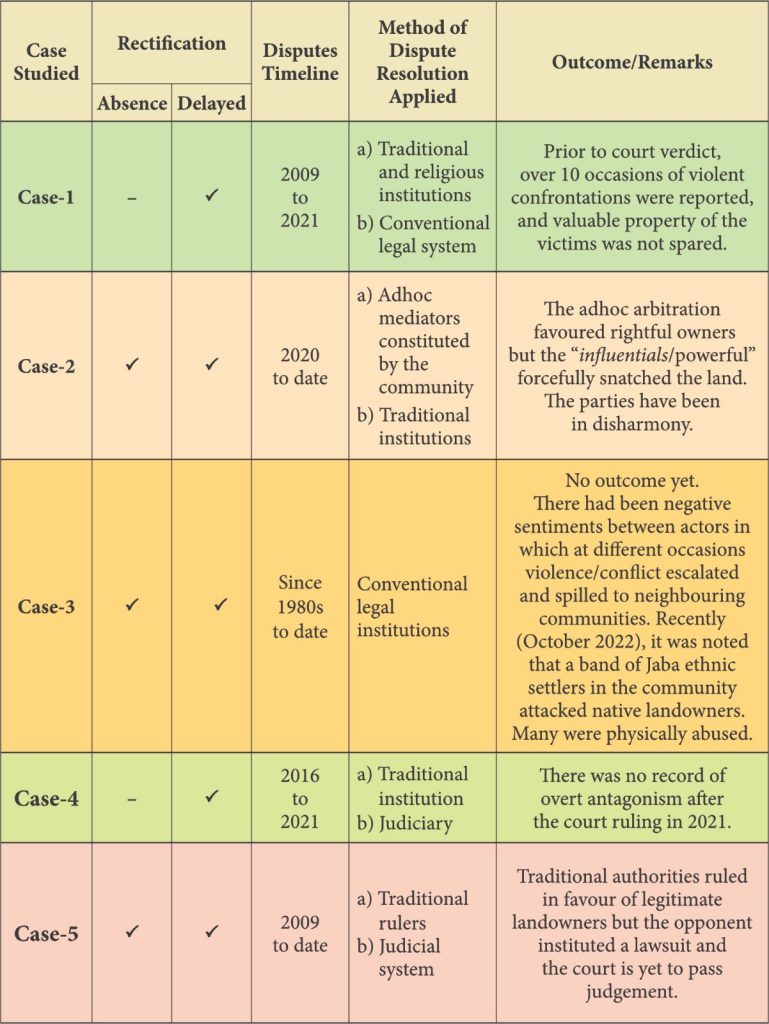

This study adopted an exploratory and multi-case study design. It involves exploring situations in which the phenomenon being investigated has no clear, single set of outcome, pattern or experience. The strategy is considered appropriate because, as scholars noted, it helps the investigator deal with multiple cases, particularly land-related conflicts. Furthermore, it allows for analysis within and across settings and also for the exploration of differences and similarities between and within cases. Moreso, multiple case studies are useful for predicting similar or contrasting results based on a theory (Baxter and Jack, 2008; Naderifar et al., 2017; Strauss, 1987; Yin, 1995). For the purpose of validity and reliability, the data collection instrument was validated by two experts (professors) from the Department of Political Science, University of Nigeria, Nsukka. The choice of these experts was based on the researchers’ prior knowledge of their expertise. The research team acknowledged their observations and suggestions, and the instrument appropriately measured what it was designed for.

4.2 Study area and scope

This study focused on six villages that were plagued by land-related disputes between 2009 and 2022. They are: Hayin-Saninge, Kuda-Yeskwa, Kogomasha, Ochü and Gava-Sanvu communities, constituting five different cases, as identified in Table 1. All these communities are located in the PDA of Karu LGA, Nasarawa state, Nigeria. The PDA lies northeast of the LGA and is bounded by Keffi LGA of the state and southern parts of Kaduna state. The indigenous people of the area are known as Nyankpa or Yeskwa people. The area, including the selected communities, is highly endowed with good agricultural topography. Farming is not only the livelihood, but also the main source of income for over 80% of the inhabitants. Crops that flourish in the area include rice, maize, guinea-corn, millet, groundnuts, bambara nuts, cassava, yams, soybeans, cowpeas and a host of others. The area is also characterised by varieties of plants of significant economic value and utility and other natural resources. Since the 1960s, this area has witnessed a gradual influx of different people from within and outside the state, in search of ‘greener pastures’ (fertile land) to cultivate crops. Among these settler farmers are the Koro, Mada, Jaba (Ham), Tiv, Eggon, Ninzo, Berom and the Ngas people, who were accommodated by the aboriginal communities in various settlements in the PDA, including the studied communities. Many of them have lived and inter-married in the area for more than 50 years.

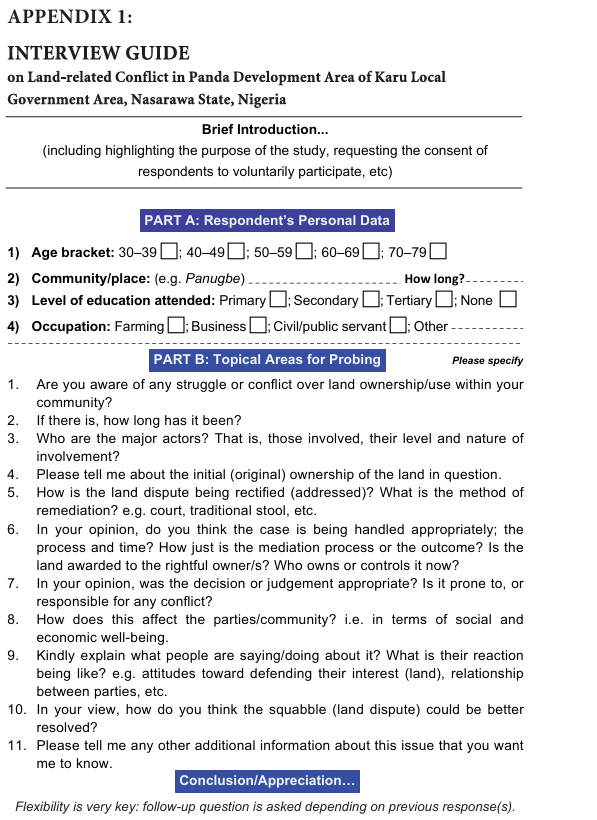

Table 1: Study locations and interviews particulars

VH/CL = village head/community leader

T/CC = typical/concerned citizens

Source: Authors (2022)

It is imperative to note that in earlier years, the host communities allowed most of these settlers to settle around them at little or no cost. But in recent years, some of them, especially their now grown-up offspring, claimed ownership of the land they occupy and cultivate. Three of these communities where this was evident (cases 1, 3 and 4) were purposively selected for this study (see Tables 1). Also, clashes over landholding exist among the indigenous people of the same community or between communities. Two such cases (2 and 5) were investigated (see Tables 1). Although the patterns of these cases and contestations were not exactly the same, they are commonly linked by the phenomenon of delay and unsatisfactory remediation, degenerating into violent confrontations. The fieldwork was conducted between 11 February 2022 and 11 August 2022 (see Table 1).

4.3 Data collection and analysis methods

Relying on the survey method of data collection, the study drew data from primary sources using a combination of purposive and snowball sampling techniques. In line with these techniques, the researchers initially identified eight respondents who were very familiar with the investigated land disputes. Through these respondents, 12 others were identified. With ethical considerations in mind, 20 key informants were approached for in-depth interpersonal interviews, but only 13 agreed to participate fully (see Table 1).

To achieve dependability, credibility, confirmability and correctness of the information, no fewer than two key informants were selected for each case investigated. Specifically, the interviewees were selected carefully based on their in-depth knowledge about the disputes or the land in question. Eight were chosen from among the land disputants, while the other five had first-hand information about the disputed lands. Also, the age bracket of respondents was considered in the selection process because, as noted by some of the respondents, age plays a significant role in native land matters. Among the participants, only one person was 35 years old; the remaining 12 were between 47 and 72 years old, some of whom were village heads (VHs) and community leaders (CLs) with deep-seated knowledge of their respective localities (see Table 1). Other factors considered for selecting participants included years of residency (at least 30 years) and reputation (integrity, without fraudulent record, etc.).

With the consent of each participant, oral interviews were conducted and recorded using an audio recording device to ensure accuracy in reporting their respective accounts. Ten interviews were done face-to-face; while the remaining three were conducted through phone calls with the aid of a semi-open-ended interview guide (see Table 1, Appendix 1). With distributive justice in mind, the instrument was designed to bridge the established gap in the literature, and thus address the research question (see Appendix 1). The voice notes were meticulously transcribed, organised and objectively analysed using the qualitative descriptive method of analysis— specifically, via narrative analysis. As scholars noted, the strategy typically allows investigators to offer a wide-ranging or detailed qualitative data description, leading to deeper insight of the subject matter (Baxter and Jack, 2008; Strauss, 1987). It involves examination of experiential stories shared by respondents, interpretation, integration and description or explanation of the data within the context of the study. Through this method, therefore, the data was explanatorily analysed within the ambit of Nozick’s (1974) theory of distributive justice, embellished with participants’ narratives, with their permission.

5. Findings and analysis

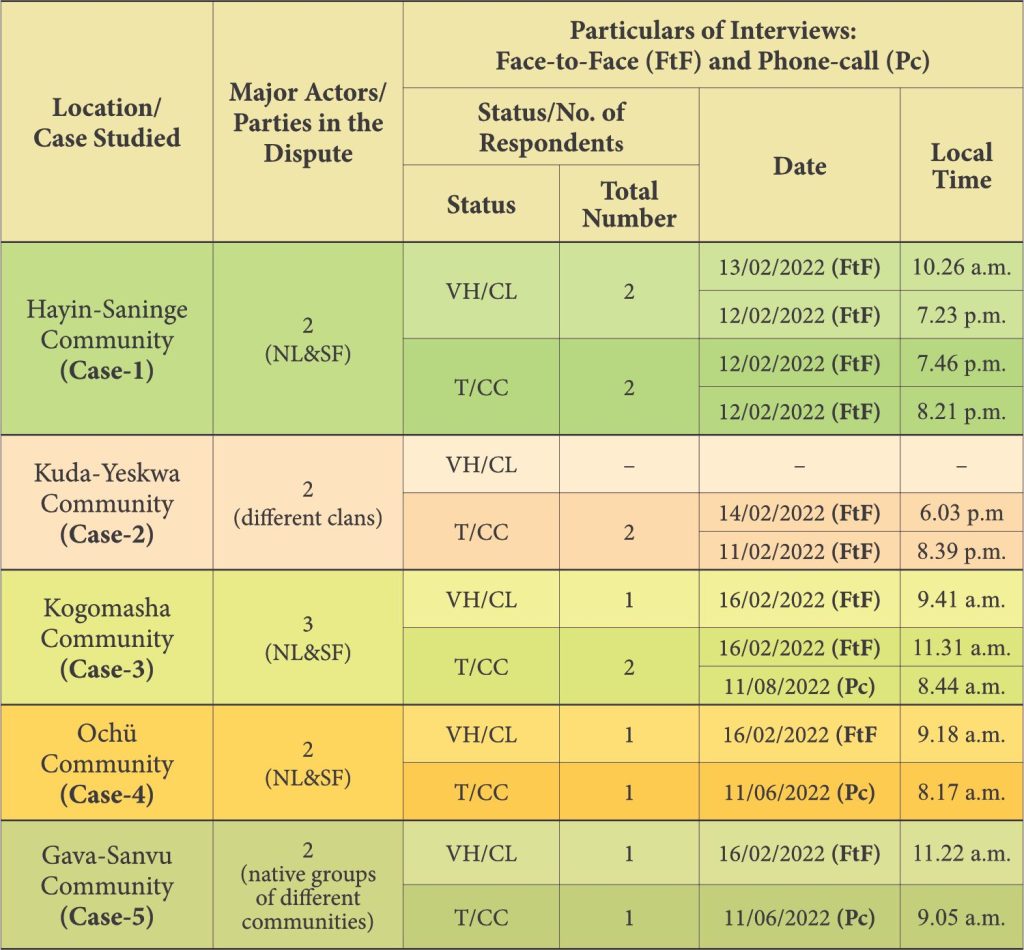

The summary of participant responses is presented in Table 2. It shows how delay and unsatisfactory resolution of land disputes account for the escalation of communal conflicts and the resultant impact on the study area.

Table 2: Retification of injustive in landholdings and land-related communual conflicts in PDA (2009-2022)

Five cases were investigated and only two (40%) of these (Case-1 and Case-4) had been successfully resolved after many frustrating years of dawdling processes and adjudication (see Tables 1 and 2). Conversely, the remaining three (Case-2, Case-3 and Case-5) have yet to be addressed (see Table 2). The dispute in Case-3 is over 30 years old. Similarly, the investigation shows that the issue in Case-2 was an old dispute that started about three decades ago and was initially mediated by ad hoc arbitrators. The squabble resurfaced in 2020 because, according to key informants, the initial (ad hoc) mediators lacked the force of law and constitutional power to sanction or enforce their resolution and decision on violators. It was also noted that delays in the rectification of unjustly held landholdings and related fraudulent claims has direct and indirect effects on the people. It does more harm than good on the sociocultural and economic life of the communities investigated. For instance, it upturns their previously harmonious relationship into distrust and disunity, and in some places, it breeds social and residential segregation. This finding corroborates what many scholars report elsewhere (see, for example, Bruce, 2013; Issifu, 2021; Zachariah and Olisah, 2020). According to these reports, communal conflicts led to the killing of thousands of people and the destruction of properties. It also exposed individuals to the use of dangerous weapons (Ali et al., 2014; Oji et al., 2015) against neighbours and acquaintances with whom they had lived together in peace.

The study gained practical insights about the subject matter from the various respondents (see Table 2). Some of their experiences and narratives are captured in the excerpts below.

In one of the interviews about Case-1 that involves Yeskwa natives and Mada settlers in Saninge, Dennis (the spokesperson of the Yeskwa people in the resolution process) stated:

It took the court several years to rule over the matter. During that period, there was [a] high level of tension in not only our community, but also the entire area. It also brought about hostility and barbaric attacks perpetrated by Mada settlers. Honestly speaking, the unnecessary delay in [the] court ruling gave rise to various barbaric acts perpetrated in our community. …because everything stopped immediately after the ruling and reward/fines…

An interviewee (a settler Nyankpa farmer) narrated:

One fateful Sunday during the early stage of the squabble, I was standing before the pulpit beside the altar to give routine [weekly] announcement as the Secretary-General of the Church. Then one of those people who wanted to take over the land, approached me with a paper and stood in my front gazing at me. When I unfolded the paper, there was nothing meaningful written on it except some irregular lines, roughly designed with [a] red pen. On raising my head, some members from the congregation signalled me to remain calm, because they saw a giant knife hanging on the assailant’s waist implying that he approached me with ulterior motive. So, after a while, he left since I didn’t yield to his plan. … They persistently threatened and attacked us who did not support their claim over the land, which compelled us to build another church away from them. We decided to disengage ourselves from them because our relationship was characterised by bitterness. Similarly, farming activity reduced significantly due to the nature of the conflict. Mind you, about 98% of our population relies heavily on crop farming, and since less farming translates to low income, we were affected drastically.

Another informant (a settler farmer in the community) noted:

While the case was still in court, [an] agitated group of Mada settler farmers unleashed violent attacks severally against some of us [co-settlers] and the main landowners. They vandalised some valuable properties worth millions of naira. In some instances, they came at night while we were asleep, and some of the victims were blatantly beaten/injured. In fact, there was this occasion in which police officers from Panda Division couldn’t calm the situation and even when [a] few soldiers were deployed to the scene, they were overpowered until there was reinforcement from Keffi Army Barracks, who applied [maximum] force on some of the notorious assailants. There were many times of unrest until after [the] court ruling over the matter in 2021.

Responses on Case 3 revealed that the dispute was between the indigenous Nyankpa/Yeskwa people of Kogomasha (first party) and two other actors (i.e. second party and third party). The second party was identified as a Nyankpa person from Barde, Jaba LGA in Kaduna state. There are three villages (Maibiri, Darigo and Angwan-Ayaba) under Nasarawa state that separate the first party from the second party located in Kaduna state. According to an interviewee:

The truth is that one of the indigenous families [Ekpo family] entrusted part of the land in question to [the] second party who requested for it to cultivate. But at the demise of Mr Ekpo, the second party claimed that the land and its surrounding[s] belong to him, against which my people charged him to court for remediation since [the] 1980s, and the court delayed its ruling. The immediate family continued with the case after [the] second party [principal actor] died.

Furthermore, the third party in Case 3, according to the investigation, comprised Jaba settler farmers, also called “Ham people” who historically originated from Kaduna state. They were hosted by the first party when the former also came in search of ‘greener pastures’ in the area around the 1970s. However, the indigenous people who gave the third party permission to use the land, told them to stop using it, because it was under the court’s restriction due to an ongoing lawsuit with the second party. According to a respondent, “Jaba settlers dishonestly claimed ownership of the land so that they may be shield[ed] from the court order and continue to enjoy the fruits of the land” unquestioned and unhindered. Consequently, they were also driven to the court by the first party. Investigations further revealed that the court’s failure to promptly address the initial lawsuit between the first and second parties was obviously the motivating factor for the third party’s claim over the land, which further culminated in distrust, social tension, violent antagonism and economic setbacks in Kogomasha.

Describing some of their experiences, an interviewee (a traditional title holder) lamented:

The last time we [first party] suffered attack from the Jaba people [it] attracts the attention of [the] State Criminal Investigation and Intelligence Department. We were threatened and violently attacked, in which many sustained various degrees of injuries and so forth. So, we filed a separate court case against them for assaults and attempted murder. After thorough investigations, they were found guilty, and in January 2022, judgement was passed in our favour. … However, so long as [the] struggle over the landholdings remains unsettled, the community is prone to conflict because, for example, if Mr “A” goes there, Mr “B” will say, “I won’t accept that,” and Mr “C”, too, will also say, “No, the land belongs to me, I will not leave them”. In fact, each party waits in suspicious (sic) of the other, such that despite the court injunction over the land, sometimes Party “A” or “B” or “C” will sneak in and extract some valuable things like palm fruits, woods/planks, etc., and when other part[ies] get to know of it, [it] often result[s] in violent confrontations.

In another land dispute (Case 2) between two clans in Kuda-Yeskwa — the ā-bé Dyong (people from the ruling family) and the ā-bé Asawu (people from the Asawu clan) — it was noted that the matter was mediated by ad hoc arbitrators, elders of the village and Ajir-utep (all adult male children of indigenous daughters of the Village from within and outside). It was also tried by Hakimi (district head) and the Odyong Nyankpa (paramount ruler) of the Panda chiefdom. According to a respondent (an indigenous member of the community):

The ā-bé Dyong claimed that the land in question was entrusted to one, late Mr Musa from Asawu’s family that they gave him when he requested for a farmland because their own (ā-bé Asawu’s) was a bit far, and since his mother hails from them (ā-bé Dyong), they allowed him to use it… But the Asawu offspring said none of their kinsmen say somebody entrusted to them any part whatsoever. They asked, “Why is it that ā-bé Dyong didn’t claim the land while Musa was alive until after many decades of his demise?”

However, the study further gathered that the elders and Ajir-utep mediated between the disputants. Their outcome did not favour the ā-bé Dyong, because the latter’s claim over the landholdings was fictitious. According to an elder statesman in the community, “Reputable elders from three other clans [ā-bé Ajingba, ā-bé Ankapa, and ā-bé Awang] testified that they were aware that ‘both parties share [a] land boundary, but the boundary area is far from where ā-bé Dyong claimed ownership …’” Therefore, the land in question was adjudged to be of ā-bé Asawu. However, the ā-bé Dyong vehemently rejected the outcome, and the matter was subsequently referred to the traditional stools of Hakimi and Odyong Nyankpa, who asked the disputants to “come back home and settle” their mêlée amicably. In view of the above, an interviewee recounted:

In our efforts to address the matter peacefully, one of the Ajir-utep made reference to an earlier statement “by a fellow[late]” who once told ā-bé Dyong to “kill the boy and take over the land” in an attempt to “nail” the same issue when “another fellow [late]” initiated it about 30 years ago.

The interviewee continued and reported that some salient questions emerged from the above factual revelations, as recounted below:

Why is it that ā-bé Dyong did not push the matter further or assume ownership of the land after the statement above? Certainly, they did not, because they knew that the truth had been said without fear, nor favour. Also, “what happens or who has been using the land afterwards?” Of course, it was ā-bé Asawu with no hindrance or contestation… But since ā-bé Dyong insisted that the land belongs to them, the elders and Ajir-utep decided that: “Let us assume that your claim of entrusting the land to late Musa is true. He is no more, but his children have been taking care of it till now. Customarily, if, for instance, you give somebody a female fowl or something to take care of and you later come for it, you are expected to give the person [a] considerable share of that which was entrusted to him/her as a way of appreciation for [a] job well done rather than antagonistically seize everything which was supposedly entrusted to…”On that premise, the mediators planned to divide the land into three and to allocate a combination of two to ā-bé Dyong and the remaining one to Asawu kindred.

However, it was noted that all efforts to reconcile the disputants by the local arbitrators proved abortive. It was gathered that this was due to the fact that the mediators lacked the power to enforce decisions. For example, an informant reported:

…ā-bé Dyong aggressively said: “Over our dead body to give them [ā-bé Asawu] that portion of land…we can only cut a maximum of three plots to them. … They should either take or forget it.” In response, ā-bé Asawu objected that “…instead of taking three plots as a remedy, let’s go back to Odyong Nyankpa for justice to take its course.” Sincerely speaking, they thought that the paramount ruler will impartially look into the matter promptly as the elders and Ajir-utep did. Instead, he restricted both parties from the land. However, ā-bé Dyong capitalised on that and forcefully took over the land and even sold part of it. And when they reported, the King didn’t take any drastic action against them.

Furthermore, the interviewee opined thus:

It is obvious that justice has been delayed/denied since the land was not awarded to the rightful owners. Nevertheless, justice and history can never be buried forever, because in the nearest future, the matter can be resurrected and justice reclaimed by the suppressed.

Meanwhile, the land dispute in Case 5 was between people of two neighbouring communities—a family in Gava community (first party) disputing against another family in Sanvu community (second party). According to the research findings, the second party in the dispute invaded a farmland belonging to the first party, from which they illegally felled some plants for their personal and commercial purposes without the latter’s consent. This matter was presented, first, before a village head at Sanvu and subsequently to the Hakimi at Tattara. Both leaders critically evaluated the case and passed judgement in favour of the first party. A respondent explained:

In one of the sittings at Hakimi’s Palace, the eldest person in [the] second party kindred addressed his kinsmen saying, “Are you older than me that you know our boundaries better than I do?” Then he said, “The place you are struggling for is the ancestral land of Gava people and at this, my age, I will never sheepishly support you to do that…” After everything, the land was awarded to [the] Waintai family by the Hakimi. But they refused to abide by the outcome and rather took legal action. So, in one of the hearings in which witnesses were examined, the first person who filed the case on behalf of [the] second party couldn’t provide any witness but rather testified in the court that trees in the disputed land were his witnesses… Following his inept statement, the court interrogates him saying, “Where were you when your opponents were using the land? Have you ever use[d] the land or cut trees from there apart from your previous activity?” He couldn’t say anything reasonable in response and the case didn’t proceed further. But surprisingly, his brother filed a fresh lawsuit in the same court, claiming that the first person “was on his own…” Unfortunately, for many years now, the case has not been settled, and they have been confronting the landowners to relinquish part of the land to them. Their previously friendly relationship has since been hostile.

From the foregoing, it can be observed that Case 2 was initially mediated by local (ad hoc) arbitrators, while traditional stools initially managed Case 5 and Case 4 (see Table 2). After thorough investigations, they dispensed justice without delay. This may not be disconnected from the fact that the traditional rulers —local mediators — know much about their environment, people and applying the right methods and mechanisms in resolving native land-related disputes. This might explain why many key informants opined that elders and traditional leaders are more crucial in the speedy and peaceful management of land-related disputes in their domains. An informant explained:

Land disputes should be resolved within the corridor of our traditional rulers. It is the cheapest, and yet best way to solving [sic], especially local land disputes. Honestly, going to the police or court is a waste of money, time and other resources, because experience has shown that on several occasions, the court, after listening to such cases, often advise[s] parties involved to settle their disagreement out of court, or pass[es] judgement based on the information or evidence made available to them, which often take[s] longer time than necessary. For example, the litigation between my people and Mada settlers (Case 1) was delayed for about 10 years before judgement was delivered. In some cases, truth is compromised in favour of the culprit. But reputable elders and chiefs are very familiar with lands and every person around them. That makes it much easier for them to remediate on such issues, better than external bodies such as lawyers, judges, etc.

Scholars have identified factors responsible for the delay in criminal justice administration in Nigeria’s judicial system, which revolve around court processes and corruption (Agbonika, 2014:130-138; Ayuba 2019:1-22). In this study, however, it is argued that delays, particularly in the resolution of injustice and conflict are extremely dangerous. Injustice persists in society, not because society in itself is bad, but because of the evil nature of some human beings, in particular those responsible for its suppression or elimination refused to speak or act appropriately. This implies that the prevalent communal feuds that resulted from unnecessary delays, unsatisfactory resolution of fraudulent claims and unjustly held landholdings in the PDA will continue to truncate justice and justify injustice, as long as those responsible for voicing or taking appropriate action continue to resort to indecision and deferrals.

In relation to injustice in the distribution of holdings, Nozick (1974:152) maintains that human history is not only one of just acquisition and transfer, but also of unjust exchanges such as conquest, slavery, theft, fraud and forceful exclusion. He further raised the following questions in relation to addressing such injustices in society:

If past injustice has shaped present holdings in various ways, some identifiable and some not, what now, if anything, ought to be done to rectify these injustices? What obligation do the performers of injustice have toward those whose position is worse than it would have been had the injustice not been done? Or, then it would have been had compensation been paid promptly? How, if at all, do things change if the beneficiaries and those made worse off are not the direct parties in the act of injustice…? Is an injustice done to someone whose holding was itself based upon an unrectified injustice? How far back must one go in wiping clean the historical slate of injustices? What may victims of injustice permissibly do in order to rectify the injustices being done to them, including the many injustices done by persons acting through their government [or legal institutions]?

The expression above implies that remediation of injustices and prevention of conflicts over landholdings lie in the prompt and just application of the principle of rectification through the lens of historical evidence of how a distribution of such land came about, that is, “information about previous situations and injustices done in them as well as about the actual course of events that flowed from such injustices, until the present” (Nozick, 1974:152). This principle of Nozickian distributive justice reveals information about the holdings and the process of its acquisition, to show whether the claimant or holder of a particular resource is truly entitled to it or not. In Nozick’s (1974) view, as far as distributive justice is concerned, this principle is essential, and without it, “if there has been a single injustice in the history of a political community, no matter how far back, such community cannot be able to achieve a just [re]distribution of resources in the present” (1974:153). In other words, landholdings that are acquired through unjust means require prompt and just application of rectification mechanisms to correct such injustices. Moreover, Nozick (1974) states that on no account should a holding be taken without the clear knowledge and permission of the rightful owner, as it would amount to injustice. According to him, “If the actual description of holdings turns out not to be one of principle [of initial acquisition or just transfer], then one of the descriptions yielded [rectification] must be realised” as promptly as possible (Nozick, 1974:152–153).

Based on empirical findings, this study departs from the views of many scholars who regard natural-resource abundance in developing countries as a curse and a cause of development crises, while others contextualise it in resource- and country-specific conditions (see Ngwu and Ugwu, 2015:422–433). According to Ngwu and Ugwu, “Whether or not natural resources are detrimental to a country’s socio-economic and political developments, depends on a number of contextual variables divided into country-specific conditions and resource-specific conditions” (2015:423). On the contrary, this study contends that abundant natural resources in themselves are not the problem of, or detrimental to a country’s development— be it country- or resource-specific conditions. Rather, they are a blessing. In view of this, the study argues that everything that God created was good and perfect and was made for humans’ well-being and happiness (Hoffman and Graham, 2009:90). Therefore, the problem lies in how humans harness or manage them, denoting that it was in the process of acquiring or harnessing the natural resources (holdings) that problems evolved. Worse still, the lack of prompt and just rectification of those (resource-related) problems account for distrust, frustration and agitation that fuels the further escalation of animosity and intra-and inter-communal conflicts in various societies, including the PDA. Thus, the just and prompt application of the principle of rectification of injustices related to landholdings is significant in not only ensuring equitable land distribution and peace among humans, but also sustainable development, particularly in the study area.

6. Conclusion and recommendations

Land is of great importance in Nigeria, particularly in the PDA—an agrarian society with good topography in which over 80% of the population depend on agriculture. This study found that most claims over landholdings in the area did not conform to the principles of distributive justice, as espoused by Robert Nozick, and that this culminated in recurring disputes and litigations. It further found that avoidable delays, unwarranted restrictions of access to land and unfavourable rectification of claims over landholdings have been responsible for various social unrests and communal conflicts in the area. Thus, we conclude that land-related communal feuds stem from deprivation and the lack of the prompt resolution of disputes related to land use and landownership, about which deliberate efforts were made to seek justice and satisfaction using available means by the aggrieved parties. The study further revealed that traditional institutions and ad hoc arbitrators of land-related disputes were relatively faster, less corrupt and more cost-effective than the formal judicial processes in resolving such conflicts. Unfortunately, the efforts of such institutions do not have the formal backing of the law and this has hampered their effectiveness.

Based on the above findings, we therefore recommend the constitutional recognition of the role of traditional institutions in adjudicating land disputes to ensure strict compliance with their resolutions. This will help to drastically reduce the timeline for the settlement of land-related disputes, which currently could drag for 30 years or longer in the formal court processes. We also recommend the fundamental reform of Nigeria’s justice system as it relates to land matters. Such reforms should consider the introduction of special courts and the mainstreaming of traditional institutions, as well as local and ad hoc arbitrators into the dispute-resolution mechanisms to accord with the Nozickian principle of distributive justice, which is itself embedded in the natural law principles.

Acknowledgements

We sincerely thank our respondents who fully participated in this research. We are also grateful to the anonymous peer reviewers and editorial board members at AJCR for their invaluable comments and suggestions during the review process of the manuscript.

References

Adegbami, A. and Adeoye, J.O. (2021) Violent conflict and national development in Nigeria. Hatfield Graduate Journal of Public Affairs, 5 (1), pp. 1–22.

Adetula, V.A.O. (2014) Land ownership, politics of belonging and identity conflicts in Nigeria: sectarian violence in the Jos Metropolis. Paper presented at the Nordic Africa Institute (NAI), Internal Research Seminar, January 8, in Uppsala, Sweden.

Agbonika, J.A.M. (2014) Delay in the administration of criminal justice in Nigeria: issues from a Nigerian viewpoint. Journal of Law, Policy and Globalization, 26, pp. 130–138.

Ahon, F., Agbakwuru, J. and Iheamnachor, D. (2021) Insecurity: southern governors offer 10-point solution. Vanguard News, 12 May.

Ali, A.Y, Lagan, A.N, Joshua, S, Peterside, Z.B, Danjuma, A.K. (2014) An assessment of the effects of communal conflicts on production and income levels of people living in Takum and Ussa local government areas of Taraba State, Nigeria. International Journal of Science and Technology, 2 (7), pp. 308–314.

Ayuba, M.R. (2019) Justice delayed is justice denied: an empirical study of causes and implications of delayed justice by the Nigerian courts. [Internet]. Available from <researchgate.net/publication/334443381> [Accessed 16 June 2022].

Baxter, P. and Jack, S. (2008) Qualitative case study methodology: study design and implementation for novice researchers. The Qualitative Report, 13 (4), pp. 544–559. [Internet]. Available from <https://nsuworks.nova.edu/tqr/vol13/iss4/2/> [Accessed 24 January 2022].

Bruce, J. (2013) Land and conflict: land disputes and land conflicts. US Agency for International Development (USAID), Washington DC [Internet]. Available from <https://www.un.org/en/land-natural-resources-conflict/pdfs/GN_ExeS_Land%20and%20Conflict.pdf> [Accessed 19 January 2022].

Elugbaju, A.S. (2018) Ife-Modakeke crisis (1849–2000): re-thinking the conflict and methods of resolution. Journal of Science, Humanities and Arts, 5 (8).

Hoffman, J. and Graham, P. (2009) Introduction to political theory. Second edition. England, Pearson Education Ltd.

Issifu, A.K. (2021) Theorizing the onset of communal conflicts in northern Ghana. Global Change, Peace and Security, 33 (3), pp. 259–277.

Kingston, K.G. and Oke-Chinda, M. (2016) The Nigerian Land Use Act: a curse or a blessing to the Anglican Church and the Ikwerre ethnic people of Rivers state. African Journal of Law and Criminology, 6(1), pp. 147–158.

MercyCorps. (2015) The economic costs of conflict and the benefits of peace: effects of farmer-pastoralist conflict in Nigeria’s Middle Belt on state, sector and national economies. Policy brief, July.

Mukherjee, S. and Ramaswamy, S. (2007) A history of political thought – Plato to Marx. India, Prentice-Hall.

Naderifar, M., Goli, H. and Ghaljaie, F. (2017) Snowball sampling: a purposeful method of sampling in qualitative research. Strides in Development of Medical Education, 14 (3).

Ngwu, C.E. and Ugwu, A.C. (2015) Rentierism and the natural resource curse: a contextual analysis of Nigeria. Journal of Social Sciences and Humanities, 1 (4), pp. 422–433.

Njoku, F.O.C. (2019) Introduction to social and political philosophy. Enugu, University of Nigeria Press.

Nozick, R. (1974) Anarchy, state, and utopia. Blackwell, Oxford, UK and Cambridge, USA.

Odoemene, A. (2012) White Zimbabwean farmers in Nigeria: issues in “New Nigerian” land deals and the implications for food and human security. African Identities, 10 (1), pp. 63–76.

Oji, R.O., Eme, O.I. and Nwoba, H.A. (2015) Human cost of communal conflicts in Nigeria: a case of Ezillo and Ezza-Ezillo conflicts of Ebonyi State (2008–2010). Arabian Journal of Business and Management Review, 4 (6), pp. 1–22.

Olivecrona, K. (1974) Appropriation in the state of nature: Locke on the origin of property. Journal of the History of Ideas, 35 (2), pp. 211-230.

Osegbue, C. (2017) The nature and dynamics of land-related communal conflicts in Nigeria. International Journal of Humanities and Social Science, 7 (7), pp. 74–86.

Otubu, A.K. (2015). The Land Use Act and land ownership debate in Nigeria: resolving the impasse. SSRN Electronic Journal. Available from: <http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2564539> [Accessed 26 June 2022].

Palik J., Rustad, S.A. and Methi, F. (2020) Conflict trends in Africa, 1989–2019. PRIO Paper. Oslo, Peace Research Institute Oslo (PRIO) [Internet]. Available from: <https://www.prio.org/publications/12495> [Accessed 26 January 2022].

Strauss, A.L. (1987) Qualitative analysis for social scientists. New York, Cambridge University Press.

Udoekanem, N.B., Adoga, D.O. and Onwumere, V.O. (2014) Land ownership in Nigeria: historical development, current issues and future expectations. Journal of Environment and Earth Science, 4 (21), pp. 182–188.

Yin, R.K. (1995) Case study research: design and methods. Third edition. Thousand Oaks, CA, Sage Publications.

Zachariah, J.O. and Ngwu, E.C. (2024) Land predation and socioeconomic dislocation in Kuda-Kenga communities of Panda Development Area, Nasarawa State, Nigeria. FUWukari Journal of Social Sciences, 3 (2), pp. 118–148.

Zachariah, J.O. and Olisah, C.I. (2020) Violent crisis and economic development in Wukari local government area (LGA) of Taraba State, Nigeria. International Journal of Innovative Research and Development, 9 (10), pp. 36–57.

Appendix