Abstract

In situations characterised by armed conflict and climate change, can informal institutions resolve conflict around shrinking resources? It is widely acknowledged that low state capacity increases the likelihood of violence in the context of climate change. In such context, informal institutions should play a crucial role in preventing and mitigating violence in the absence of formal institutions. However, little is known of the characteristics of these informal institutions and existing literature on climate change and conflict has examined them in isolation from national contexts and actors. This paper seeks to address this gap and argues that impartiality is essential for the ability of informal institutions to resolve resource-based conflict, a by-product of climate change, and prevent violence escalation. However, when institutions are partial, because of co-option by the state or other external actors, their decisions may further increase communal violence and prolong civil conflict. Partial institutions can encourage people to take justice into their own hands, and push individuals to join rebel groups offering more favourable options in redressing grievances. This theoretical argument is explored through a case study on central Mali, where partial informal institutions, in conjunction with other factors, have led to increased violence in the region.

1. Introduction

In situations characterised by armed conflict and climate change, can informal institutions resolve conflict around shrinking natural resources? In the last decade, concerns have increased about the link between climate-related shocks affecting agricultural production and food security as a factor in armed conflict. However, most scholars recognise that environmental scarcity (increasingly induced by climate change) is rarely the sole – or sufficient – cause of large-scale violence. Instead, they point to the importance of economic, political, and social factors in influencing the environment-conflict linkage (c.f. Mach et al. 2019). It is therefore essential to examine climate factors together with other conflict drivers – such as the functioning of institutions – to avoid simplistic causal pathways between climate change and conflict. This article explores which factors makes informal institutions (un)able to mediate conflict in a context of climate change and scarce resources in central Mali.

Informal institutions are particularly important in fragile countries with weak formal institutional presence (Menkhaus 2007). According to the United Nations, 80% of conflicts are managed through informal justice mechanisms in most developing countries (UN 2019). While informal institutions have long been studied for their role in managing natural resources (c.f. Ostrom 1990), their role in mitigating the negative effect of climate-induced resource scarcities on violent conflict has yet to be fully defined. Indeed, previous research has indicated that informal institutions can increase tensions (Raleigh 2010; Benjaminsen 2008) or decrease them (Bogale and Korf 2008). The most recent study on the topic argues that while traditional or customary rules may moderate conflict risk in some contexts, this is not true in all places (Linke et al. 2018:30). This article intends to provide insights into why some informal institutions supposedly created to resolve conflict around resources fail to do so in the context of climate change, scarcities and ongoing armed conflict.

The study argues that informal institutions do not operate in a vacuum and are influenced by several actors, particularly the state, local elites and existing rebel groups (c.f. Brosché and Elfverson 2012; Walch 2018). Looking at the informal institution of the Dioros, one of the most important institutions in charge of resolving conflict around natural resources in central Mali, this article argues that the influence of, and co-option from the state has impacted the impartiality of the institution, reducing its ability to resolve conflict. As a result, the Dioros are no longer perceived as providers of impartial decisions, affecting their role as neutral arbiters mediating conflict between herders and farmers in the central region of Mali. The lack of impartiality of this informal institution allows communal disagreements around access to resources to escalate, as aggrieved parties may choose to impart justice themselves or join rebel groups, intensifying and prolonging the ongoing civil conflict in Mali. Rebel groups may also actively gear their recruitment’s efforts in zones lacking resources and where there is a high level of dissatisfaction with existing institutions (Walch 2018; SIPRI 2020).

By exploring the role of informal institutions in situations of climate change, resources scarcity and conflict, this article makes three main contributions to existing literature. First, it provides new insights into causal mechanisms between climate shocks and conflict. While existing research has highlighted the importance of exploring institutions and actors (Buhaug 2015; Koubi 2018), few studies have actually provided an in-depth examination of these context-specific dynamics. Second, this article also contributes to the literature on institutions and civil wars, by showing how biased informal institutions can fuel existing armed conflict (c.f Wig and Tollefsen 2016). It provides additional evidence that when informal institutions fail to provide impartial judgement in matters related to justice, security and access to resources, rebel groups are likely to profit from this partiality, capitalising on the frustrations they engender among citizens. Armed groups may, in fact, gear their recruitment strategies towards these particularly aggrieved populations. Third, this article provides rich evidence of how communal violence feeds into civil war dynamics, by creating a need for security and justice that rebel groups can meet. It indicates how localised violence contributes to larger civil wars dynamics (Brosché and Elfversson 2012; Krause 2019).

The study is organised as follows. First, the article briefly reviews the existing research on climate change and armed conflict, demonstrating the importance of exploring institutions and actors for understanding causal mechanisms. Second, the article develops an argument about the impartiality of informal institutions and their (un)ability to mediate conflict around scarce resources. After discussing case selection and methods, the third section explores the role of the informal institution of the Dioros in the central region of Mali. The last section concludes the article offering avenues for future research.

2. Point of departure

Climate change continues to exacerbate the impact of hazards on agricultural production and on natural resources such as water and vegetation (Cohn et al. 2017). These effects are already felt by various communities worldwide and are projected to increase in the future (Calzadilla et al. 2013). According to experts, climate change is increasing the intensity and frequency of a variety of natural hazards, such as heat waves, floods, and storms, which have negative impacts on agricultural and livestock productivity (Cohn et al. 2017). As a result, smallholder farmers and herders, who do not have access to modern technology and only rely on natural resources to cultivate their fields and feed their animals, are being particularly affected by the impacts of climate change (Cohn et al. 2017).

Researchers have linked loss of livelihood with conflict through the so called “opportunity cost” model. This model suggests that when expected returns from fighting outweigh income from regular economic activity, the likelihood of people joining an armed group increases (cf. Grossman 1991 and Collier and Hoeffler 2004). In other words, communities unable to survive on their traditional livelihood, will therefore consider joining an armed group as an alternative to feed themselves or their family (Miguel et al. 2004; Maystadt and Ecker 2014; Vesty 2019), particularly if they are convinced that the government is to be blamed for their misery (Hendrix and Salehyan 2012). When the state is not seen as the main cause of communities’ loss of livelihood, but another ethnic group, communal violence is more likely. Directing violence against other societal groups can prove a more efficient short-term strategy to mediate access to resources critical to sustain livelihoods (Fjelde and von Uexkull 2012). Armed groups may also direct their recruitment activities in populations who bear the brunt of the impact of climate change (Walch 2018).

While it is beyond the scope of the paper to review the rich and fastmoving literature on climate change and conflict[1], the paper takes as a point of departure that the political and institutional contexts of the conflict is crucial to understand the conditions under which climate change may increase conflict. While the opportunity cost framework is the most often mentioned link between climate and increased conflict, peace and conflict research is not always in line with this theoretical framework and indicate a more nuanced picture of participation in armed conflict, highlighting other factors such as social or ethnic bonds and leadership (c.f. Berman et al. 2011). Joining armed groups may also come with security benefits for participants (Kalyvas 2006) and other non-material benefits such as status or the pleasure of agency of fighting against perceived injustices (Woods 2003). Structural factors such as endemic poverty and weak state institutions have also been found to greatly increase armed conflict (Hegre and Nygard 2015).

Hence, more is at play in the relationship between climate change and conflict, and according to a wide variety of experts, low state capacity is a crucial factor therein (Mach et al. 2019). The role of institutions (formal and informal) is increasingly highlighted as a crucial conditional effect between climate shocks and conflict. For example, Ngaruiya and Scheffran (2016) and Linke et al. (2015; 2018) highlight the role of some local institutions and traditional conflict resolution mechanisms in mitigating the security risks posed by erratic climatic conditions. Linke et al. (2015; 2018) found that when communities value their institutions, they are less likely to use violence during times of scarcity due to drought. In examining local conditions of drought-related violence in sub-Saharan Africa, Detges (2016) found that state institutions and their service provisions – in this case road infrastructure – decrease the level of violence following climate-induced disasters. There is a rich literature on informal institutions (cf. Choudree 1999; Ogbaharya 2008; Ajayi and Buhari 2014) that has potential to theoretically inform the fast-growing literature on climate change and conflict.

Understanding micro-level variation between climate change and conflict requires both attention to the ability of the informal institution to cope with climatic and livelihood shocks and the potential conflicts these shocks may trigger. Exploring these local and informal institutions is particularly relevant as 80% of conflicts in many developing countries are resolved through informal justice systems (UN 2019). The next section explores the role and characteristics of these informal institutions in resolving conflict over resources.

3. Informal institutions and violence around resources

In many African countries, informal institutions are valued for their accessibility in resolving conflict at the local level (c.f. Ndubuisi 2017; Wig and Kromrey 2018). Defined as ‘socially shared rules, usually unwritten, that are created, communicated, and enforced outside of officially sanctioned channels’ (Helmke and Levitsky 2004:727), informal institutions often shape the political orders in these contexts (Husken and Klute 2015). For example, informal institutions have been shown to play a central role in land tenure security (Boone 2014; Honig 2017), public goods provision (Wilfahrt 2018) and conflict resolution (Ndubuisi 2017; Logan 2013; Mohammed and Beyene 2016; Wig and Kromrey 2018).

While informal institutions have long been studied for their role in managing natural resources (c.f. Ostrom 1990; Rupiya 1999), their role in mitigating the negative effects of climate variability on violent conflict has yet to be fully comprehended. Indeed, previous research has indicated that institutions can increase tensions between competing groups (Raleigh 2010; Benjaminsen 2008) or decrease them (Bogale and Korf 2008). There is therefore a strong variation in the effectiveness of informal institutions; some do better than others at addressing needs. While informal institutions may moderate conflict risk in some contexts, we know that this is not true in all places. Even within one country, certain informal institutions are influential in some areas and not at others (Linke et al. 2018), or cause tensions or place a high value on warfare (MacGinty 2008). Knowing better the conditions under which informal institutions are more likely to peacefully resolve conflict arising from climate shocks and/or resource scarcity is an important contribution to existing research.

This article argues that this variation in the ability of informal institutions to peacefully resolve conflict lies in their impartiality and capacity to be perceived as neutral arbiters by the population. ‘For an institution to act impartially is to be unmoved by certain sorts of considerations – such as relationships and personal preferences. It is to treat people alike irrespective of personal relationships and personal likes and dislikes’ (Rothstein and Teorell 2008). Impartiality is thus an attribute of the actions taken by judges, local and traditional leaders.

While the concept of impartiality has been mostly applied to formal institutions (c.f. Rothstein and Teorell 2008; Rothstein 2014), this article argues that it is equally crucial for informal institutions. Indeed, informal institutions usually give more weight to leadership compared to formal institutions and there is usually no written code of conduct or laws on how the informal institution should behave (Rothstein 2014). As the institution is often based on the inherent character and status of the leader, a lack of impartiality might therefore be even more obvious in the eyes of the community. In this vein, Williams (2010) found that impartiality is an essential trait for traditional leaders in South Africa. When leaders of informal institutions are perceived to be impartial they can more easily arbitrate the delicate issues of access to and distribution of resources in rural areas.

Impartiality is also a quality of institutions and leaders highly valued by citizens. Surveys in India clearly indicate that it is ‘very important’ that civil servants should ‘treat everyone equally, regardless of income, status, class, caste, gender or religion’ and also that the civil servants ‘should never under any circumstances accept bribes’ (Windeman 2008). In Sri Lanka, Lindberg and Herath (2014) suggested that impartiality of institutions dealing with land is crucial for peacebuilding. Similarly, a SIPRI’s study on Mali (2020) found that communities mostly trust impartial institutions.

The impartiality of informal institutions changes over time as they are not isolated from the socio-political context of the country (Roland 2004). These changes can occur abruptly because of exogenous shocks or critical junctures that lead actors to remake or re-imagine existing social institutions (Capoccia and Kelemen 2007). These informal institutions do not operate in a vacuum: the central government and opposing rebel groups may influence the institution and affect its impartiality (Walch 2018). The state and other external actors such as rebel groups may coopt or influence the leaders of these institutions and may force them to adopt certain rules over others. This behaviour may negatively affect the informal institution by reducing its impartiality. The informal leaders might be seen as corrupt and responding to its patrons rather than providing fair decisions. In being co-opted by the state or a certain rebel group, partial institutions create a very narrow reciprocal exchange with only certain members of the community at the expense of the majority. As a result of this lack of impartiality, institutions will be perceived as biased and unable to play a neutral arbiter role in mediating disputes regarding resources. This may increase violence in two interrelated ways.

First, partial institutions may push aggrieved parties to impart justice themselves, allowing for personal vendettas, riots, and communal violence. Partial institutions may antagonise some of the community members, increasing communal violence, particularly in a society divided along ethnic lines (Lieberman and Singh 2012). Communal violence – often defined as non-state armed conflict between social groups that define themselves along identity lines, such as ethnicity, religion, and livelihood – is most likely to increase when informal institutions have communal bias (Fjelde and von Uexkull 2012). In this context of partial institution, violence is used as a strategy to secure access to livelihood essentials such as land for farming and grazing or water holes, given the lack of a neutral arbiter able to mediate access to these resources. Escalation of communal violence is likely when the lack of access or dispute is related to the behaviour of a specific ethnic or livelihood group (e.g. farmer vs herder). Directing violence against other societal groups might be a more efficient short-term strategy to access to resources critical to sustain the livelihood in the absence of an impartial institution (Fjelde and von Uexkull 2012).

Second, the lack of impartiality of informal institutions over time can accumulate large-scale grievances that inspire people to take up arms against the state or join existing armed groups. In this type of rebellion, the sources of grievances must be related to the behavior of the state; for example, for its lack of response to environmental hardships. Indeed, grievances may be further increased by absent or unfair aid assistance by the state following disaster and motivate a larger pool of individuals to join and/or support an active rebel group to redress their grievances (Eastin 2018; Wischnath and Buhaug 2014). Increased recruitment and troop size will in turn increase armed conflict intensity and the number of deaths (Wischnath and Buhaug 2014).

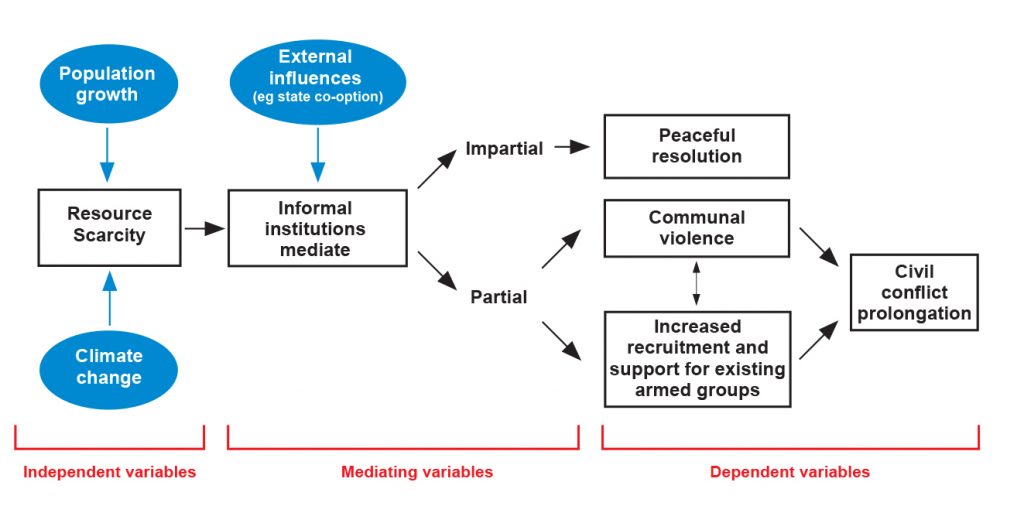

This article argues that partial institution results in increased conflict around access to resources, intensifying different types of violence and prolonging the ongoing intra-state conflict. While an impartial institution can play a neutral arbiter role in mediating tensions over resources and preventing conflict from escalating, partial and biased informal institutions may actually increase tensions and fuel armed conflict. In a context where climate change is increasing resource scarcity and therefore the need for conflict resolution mechanisms, the lack of impartial institutions is worrying for peace. The next diagram illustrates the theoretical argument made in the article. Alternative explanations are discussed in the concluding section.

Figure 1. Theoretical mechanisms

4. Methods

To explore the theoretical mechanisms mentioned in the previous section, the article takes on a qualitative method examining the case of central Mali. By exploring a single case, this study focuses on identifying micro-level dynamics, which are useful to theoretically inform existing literature, in need of ‘more nuanced theoretical approaches’ (Buhaug et al. 2015:271). An in-depth case study is particularly well suited to explore the role of informal institutions in mediating (or not) conflict around resources and armed violence. A single case study allows the researcher to obtain data that is not easily available through quantitative studies.

It also permits the researcher to carefully trace the causal process by which a disagreement around resources may escalate to armed violence when informal institutions are partial. The objective of the method is therefore to explore the theory in the context of Mali and not to test the generalisability of the theoretical framework across cases.

For theory development, it is useful to identify causal pathways and variables, which can be explored through one or more cases. To do so, this article uses process-tracing, which consists of ‘attempts to identify the intervening causal process – the causal chain and causal mechanism – between an independent variable (or variables) and the outcome of the dependent variable’ (George and Bennett 2005:206–207). Since the study attempts to establish sequential steps from cause to effect, process-tracing is a very useful method. In addition, this analytical procedure helps the researcher to uncover omitted variables and assess alternative explanations, while focusing on the main variation of interest for the study. It therefore improves theoretical parsimony and keeps some degree of explanatory richness at the same time.

Mali provides an ideal case in this regard as the country is affected by climate change and suffers from different levels of resource scarcity and violence, while it has clear informal institutions to deal with access to resources. The country therefore represents a ‘typical case’ (Gerring and Seawright 2007) and a ‘hot-spot’ for climate-conflict links (de Sherbinin 2014). A number of reports are highlighting the connection between climate change and conflict in Mali (c.f Mitra 2017, ICG 2019; NUPI 2021).

The case studies build on unique interview material collected during two field trips in 2017 and 2019 in Mali, and on data collected by a team of local researchers from the sociology department at the University of Bamako. While the author directly conducted 15 semi-structured interviews and two focus group discussions mostly in Bamako, the local research team in Mali did 40 interviews following semi-structured interview guidelines written by the author in the central region of Mali, around the city of Mopti. Typical respondents include local leaders, resource user (such as farmer, herder and fishermen), government officials, religious leaders, community groups, military personnel, UN representatives, and NGO workers. The language used in the interviews were Peul, Bambara and French (or a mixture) depending on the choice of the respondent. The questions asked were about what climate/ environmental challenges they experience, how the use of resources has changed, who is responsible for land management, the role and perception of traditional and state institutions, the relations between farmers and herders, the type of violence affecting their communities and how conflicts are managed? Questions were open-ended and were mostly used to guide the interviews. Appendix with the original questions is available upon request.

Given the level of violence in the central region, most interviewees preferred to talk anonymously. The interviews were organised according to categories of people interviewed, i.e. local official, community leader, professors/ researchers, herders, farmers and traders (see Appendix for a list of respondents). The respondents were approached through the research team’s network and ‘snowball sampling’ (Biernacki and Waldorf 1981). While this method can limit generability and bias samples because access to respondents is contingent on existing networks, personal referrals often provide the only access to respondents, especially in armed conflict settings (Cammett 2006). Having said that, the study tried to capture a broad sample of respondents with different background and views in order to get a holistic picture of the situation. Secondary documents, such as policy papers or newspaper articles are also used in addition to the interviews, facilitating ‘triangulation’ and ensuring the reliability of the data collected.

5. Informal institutions and impartiality in the contested region of central Mali

The context in central Mali

The central region of Mali has always been inhabited by different ethnic groups and cultures. Five major groups have been living in the region: the Bambara (mostly farmers), the Peul (mostly pastoralist), the Dogons (mostly farmers and hunters), the Bozo (mostly fishermen) and the Moors/Arabs (mainly traders).[2] The central region of Mali is composed of eight ‘cercles’ (or provinces) and has a population of 2 million.[3]

Over the past 50 years, natural resources, such as water and grazing land, have been under increasing stress. While rainfall fluctuates substantially from year to year, it has tended to decrease over the past 50 years (Cotula and Cisse 2007; NUPI 2021). This decrease in rainfall has in turn led to a reduction of the flooded area, and to a shortening of fertile lands (Cotula and Cisse 2007). This observation is supported by several people interviewed during fieldwork, who reported reductions in rainfalls and fertile lands.4

Communal violence between the Peul, the Dogon and the Bambara, together with Jihadist groups attacks against the Malian governments, and the Malian army’s responses to these attacks, have made the central region of Mali one of the most violent regions of the country.5 Since 2017, there are more than six rebel groups active in the central region, including Katiba Macina (KM), Ansar Dine, Al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb, (AQIM), Al-Mourabitoun, Movement for Oneness and Jihad in West Africa (MUJAO) and the Islamic State in the Greater Sahara (ISGS). Most of these Jihadist rebel groups supposedly merged together in March 2017 under the new group Jama’at Nusratul Islam wal Muslim (JNIM) (ICG 2019). The KM, with its charismatic leader Amadou Kouffa, has been of the most active groups in the region.

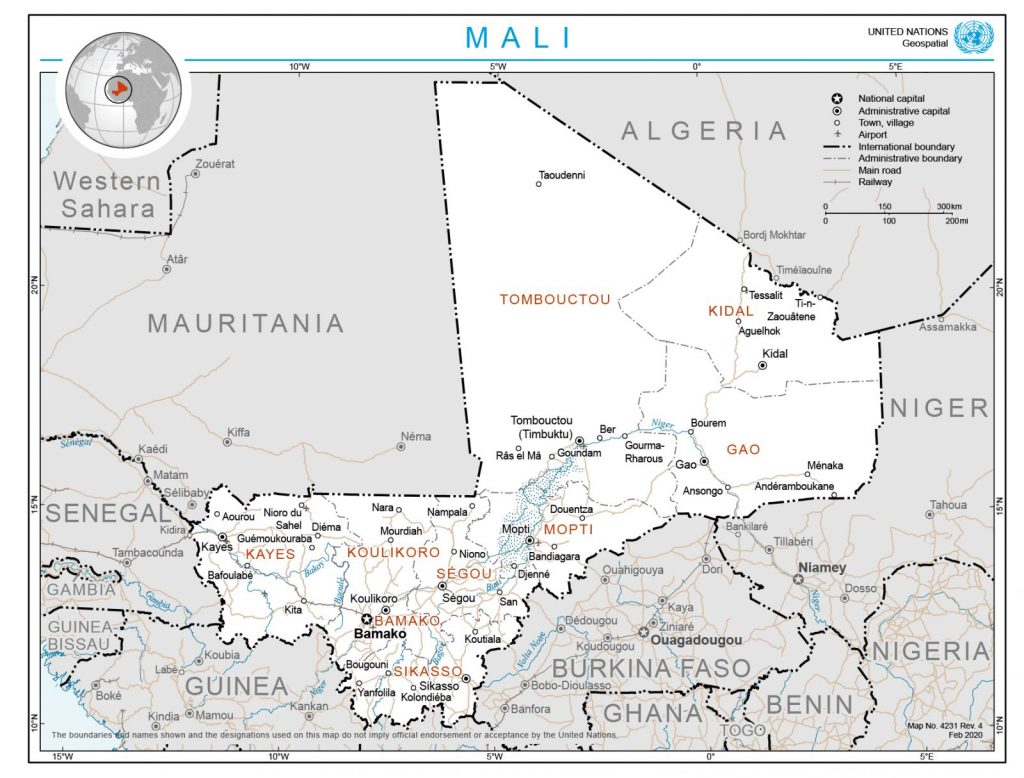

Map 1. Mali

While the complexity of resource uses and of ethnic composition have led to many different informal systems in the central region of Mali, one of the most important one in charge of resolving conflict around natural resources is the Dioros (or Jowros) system.[4] Created in the 14th century during the Ardobé period (see Turner 1999 for a full description of the history of this institution), the Dioros still play an important role in managing access to wetlands, Bourgoutière, (burgu pasture/grazing land) and in establishing entry routes for transhumance livestock (Benjaminsen and Ba 2018). The Dioros are made of local chiefs and descendants of aristocratic families who have a special status in the community.[5]

In practice, conflicting parties reach out to the Dioros in charge of the area to resolve a conflict over lands or access to resources. The Dioros usually starts by assessing each party’s grievances and calls for witnesses who can provide information around the conflict.[6] Once the Dioros has a clearer idea of what happened, a decision to resolve the conflict is given. In a typical case of a herder damaging the field of a farmer, the herder might be asked to give one of his animals for reparation.[7]

The assessment of party’s grievances and witnesses’ testimony has to be done in an impartial manner by objectively assessing grievances on both sides. From its creation, the primary focus of the Dioros was the management of common pool resources. The impartiality of the institution of the Dioros is rooted in its interest in peacefully resolving conflict on the territory under its traditional authority. Impartiality was therefore imbedded in principles of reciprocity and mutual interest. The traditional and aristocratic status of the Dioros further established its role as a neutral arbiter of conflict around access to land. However, the impartiality of the Dioros has deteriorated over time.

Deteriorating impartiality and increasing communal conflict

Increased land pressure caused by climate change, rapid population growth, and development projects favouring large scale farming have generated more communal tensions, particularly between farmers and herders.[8] As available grazing land shrinks and farmers occupy corridors previously used by animals to reach water points, herders have begun to take their animals through the farms to access water, causing significant damage to crops (Benjaminsen and Ba 2018). While usually farmers use the land during the wet season and herders access it during the dry season, climate change is affecting weather patterns (Santer et al. 2018) and this rotation in sharing the lands. Disputes arise because herders have to bring their animals to the wetlands earlier than before, sometimes before crops are harvested, causing significant damage to farmer’s fields.[9] Herders complain that farming has encroached on pastoral land leaving no choice for them but to enter the farms either for passage or for grazing (Benjaminsen and Ba 2018).

In this context of shrinking resources and needs for conflict resolution mechanisms, the informal institutions of Dioros and local officials saw it as an opportunity to ensure their power and personal enrichment. For their role in managing the land, the Dioros are usually entitled to receive rents from herders passing their lands. This rent used to be a sort of barter and was only monetised in the 1990s because of the growing scarcity of lands due to increased agriculture and larger cattle (Jourde et al. 2019). This introduction of a ‘fee’ to access pastureland was also the result of a growing collusion between state officials and the Dioros. This damaged the perceived impartiality of the Dioros and the rent was increasingly seen as extortion. Most herders feel they are unfairly taxed and that their rent has become a business for the local elite.

According to a Peul herder from Youwarou: ‘How we see the Dioros has changed. Before we saw them as traditional chiefs interested in the welfare of the entire community but now they only serve their own interests and those of corrupt government officials. Some of them have even become mayors and their decisions about land disputes always are on the sides of the farmers and other elites that are supported by the government’.[10]Another respondent argues that both informal and formal justice systems are only designed to racket the herders. To prove this point, herders explain the rent to access land has increased exponentially over the last decade and that they are not financially able to pay the access fee to ‘Bourgoutières’.[11] They believe there is a strong collusion between state officials and the Dioros to make money from the herders and favour sedentary groups involved in farming.[12]

The distrust towards the Dioros has dramatically reduced their ability to manage tensions between farmers and herders over access to water and grazing lands.[13] As mentioned by a Peul leader: ‘At the end, the outcome of informal or formal justice decision boils down to which party has more money. More money enables you to bribe local officials and Dioros or to access more jurisdictions. For example, a rich farmer has more jurisdiction to choose from than a poor Peul herder’.[14] While herders feel decisions are often taken in favour of farmers, small-holder farmers also feel that institutions are biased in favour of farmers with larger farms and connections to the government, or in favour of Peul local elites who are often landowners.[15]

With this absence of impartial institutions to resolve disputes around resources, herders, and farmers instead take matters into their own hands, creating self-defense groups or joining rebel groups.[16] Since 2016, communal conflicts have steadily increased (UCDP 2020, ICG 2020) in Mali. For example, 160 Peul civilians were killed in Ogossagou in March 2019 by an armed ethnic Dogon militia in revenge for a Peul attack a couple of days before (Le Monde 2019). This communal violence is not isolated and other attacks killed 37 Peuls in another village of central Mali in January 2019. In June 2019, it is 75 Dogons that were killed in the villages of Sabane Da, Gangafani and Yoro by Peul militias (The Guardian 2020). While violence has mostly affected Peul communities, the Dogons and the Bambara have also been hit by indiscriminate attacks, fueling a cycle of reprisals. Already in 2018, the Simon-Skjodt Center for the Prevention of Genocide had already raised the alarm by publishing a report about this increase of communal violence, mentioning the failure of conflict resolution systems as the main trigger to this spiral of violence (Ibrahim and Zapata 2018).

Aware of the lack of impartial institutions to prevent the ethnic tensions from escalating, the international NGO Centre for Humanitarian Dialogue has tried to play a mediating role between the communities and facilitated a sort of local peace agreement.[17] In this peace agreement, the importance of impartial institutions to peacefully resolve conflict in the community was clearly highlighted. An idea was to have local chiefs of several ethnic groups (Dogon, Peul and Bambara) in charge of conflict resolution to improve the impartiality of the decisions taken.[18] From these interviews with NGOs workers and community members, it is worth noting how impartiality of institutions in charge of conflict resolution was highlighted as a core factor to prevent disputes from escalating. While they claim that this local peace agreement facilitated by Centre for Humanitarian Dialogue has temporarily reduced violence in the region, it may not last very long once the NGO leaves.[19] They believe that impartial institutions, through more ethnic representation, should be more generalised and encouraged by the state to prevent armed groups from capitalising on the existing partiality of the informal institution and justice vacuum.[20]

Rebel groups benefiting from partial institutions and communal violence Jihadist rebel groups in the region have been among the first ones to decry the partiality of the Dioros and other formal institutions. Amadou Kouffa, the leader of the rebel group KM has often criticised the Dioros’ collusion with corrupt government authorities.[21] While he does not question their right to manage pastures, he denounced the partiality of the Dioros because of their collusion with the state in collecting fees from pastoralists.[22] The denouncement of these practices was very well received by the herder community who saw in Amadou Kouffa and his KM rebels an opportunity to restore a more impartial justice.[23] These rebel groups have been particularly successful in using existing cleavages, conflict and partial institutions to ensure their power and control.[24] Rebel groups have used this opportunity to increase their popularity and to justify their attacks against the Dioros and the political elite that display predatory behaviors through taxation and racketeering.[25] Some respondents said that ‘Since the arrival of KM, the Dioros and other elites cannot do what they want with the herders. They are less comfortable in imposing fees or arresting herders with the help of state official because they might be attacked by the rebel group later.’[26]

Rebel groups clearly responded to the perceived lack of impartiality in informal institutions, noticing that it was a particular source of grievances for the herders. Peul communities have long complained about the reduction of the grazing space, the high fees they have to pay to the Dioros and local authorities, and the conflicts they have with farming communities.[27] While the state ignored these grievances, JSIM (and particularly the KM) has addressed them by providing alternative justice mechanisms and by targeting corrupt officials and Dioros. This has led many Peuls to join the KM (ICG 2019). This rebel group plays a role of ‘justicier’ (righter of wrongs), which resonates well among communities that feel neglected and unfairly treated by the state and local elites (Sangare 2016).

Looking back, the rebel group’s control during 2012 was welcomed by some of the Peul community. They particularly welcomed the fact that the Dioros lost their rights in managing access to Bourgoutière and other status they may have in the society.[28] Some people interviewed from the Peul community argued that the security situation was better under Jihadist control in 2012. During this period, however, it is worth noting that the Bambara and the Dogons were particularly marginalised compared to the Peul.[29] The return of the state with the help of the French military in 2013 brought back the Dioros system and further increased the partiality of the institution who perceived the Peul community as Jihadist supporters.[30]

In such contexts of failing institutions and communal violence, the Jihadist rebel groups have gained popular support and new recruits (ICG 2019). Instead of trying to restore impartial institutions, the government of Mali response to this increasing violence has been equally biased against the Peul community, who are perceived as jihadist supporters, resulting in abuses and exactions against this community (ICG 2019). The government of Mali has tolerated and sometimes collaborated with Dogon self-defense groups involved in indiscriminate killings of Peul civilians (ICG 2019). A Peul village chief argues that his people are ‘victims of mistaken affinity,’ because for the Malian security forces, every Peul is a de facto jihadist. ‘They are killed and attacked for that. Not only civilian Peul are targeted by the army, they are also the target of militias close to the government, such as the Dogon hunter groups.’[31] The manipulation of the ethnic ties of the population by both state and rebel groups has had a detrimental effect on communal dialogue and the impartiality of institutions in the region (Sangare 2016). A local leader from Tenenkou summarises the situation: ‘The ethnic aspect of the conflict is used by the armed groups to confront people. For me, the real problem is the lack of an impartial authority, formal or informal, that is respected by the population and the armed groups.’[32]

6. Conclusion

This single case study has highlighted the importance of examining informal institutions charged with conflict resolution to fully understand the links between climate change, scarcity of resources, and increased armed conflict. The role of informal institution is crucial given their accessibility and presence in regions where the reach of formal institutions is limited. However, the ability of informal institutions to resolve conflict might not be taken as a given. Indeed, the paper indicates that when informal institutions are co-opted by the state, they lose their impartiality and ability to mediate conflict around resources and access to land. Partial informal institutions can lead people to independently impart justice and push individuals to join rebel groups that propose more favourable options to redress their grievances, increasing communal violence and prolonging civil conflict.

The vast majority of respondents mentioned that climate change is increasing the stress on already dwindling grazing and agricultural lands. While this increases poverty, the link with armed conflict is often mediated by informal institutions. However, when informal institutions do not function properly due to their partiality, an issue of resource or land access that should be a minor complaint within the informal justice system can escalate to violence involving entire communities. This feeling of injustice has reinforced the will of communities to rely only on themselves or on armed groups (rebel or self-defense militia) to seek revenge or justice, thereby contributing to the vicious cycle of violence. In such context, the best option to survive is often to join an armed group.

By unpacking the relationship between climate-related scarcities, armed conflict and the partiality of informal institutions, this paper makes three main contributions to existing research. First, it provides new insights into causal mechanisms between climate shocks and conflict. While existing research has highlighted the importance of exploring institutions (formal and informal) and actors (Buhaug 2015; Koubi 2018), few studies have actually provided an in-depth examination of informal institutions and their actual (un)ability to resolve conflict. By examining the (im)partiality of informal institutions, the paper moves beyond black box approaches and specifies causal mechanisms (Mach et al. 2019).

Second, this article contributes to the literature on institutions and civil wars by showing how partial informal institutions can fuel existing armed conflict. It provides additional evidence that when informal institutions fail to provide impartial judgement in matters related to justice, security and access to resources, rebel groups are likely to profit from this partiality and weakness in institutions, capitalising on the frustrations engendered among citizens (Wig and Tollefsen 2016). While literature on formal institutions and good governance has highlighted impartiality as an essential condition (Rothstein and Teorell 2008), the article has found that it is equally as important for informal institutions.

Third, this article provides rich evidence of how communal violence feeds into larger civil wars dynamics in the context of Mali. It also indicates that communal conflicts, which in theory do not directly challenge the national government, are not purely ‘ethnic’ and ‘apolitical’. Such conflicts do not take place in isolation from national politics and the article has shown that the central state and existing rebel groups play an important role in these communal conflicts, by siding on the side of the local elites (or fighting against them in the case of rebel groups). This provides additional evidence that communal conflicts require a thorough understanding of horizontal and vertical linkages between national and local power arrangements and customary law (Krause 2019).

The method of process-tracing used in this article has facilitated the identification of alternative explanations, while keeping the focus of the paper on the variables and factors derived from the theoretical argument. Among these alternative explanations that future research could explore is the behavior of the rebel groups and their objectives to disrupt communities and informal institutions to impose new ideological and political orders. In order words, these groups may have autonomous imperatives and their presence or impact need not be seen as a mere byproduct of resource-driven conflict. Indeed, there is evidence that they actively take advantage of climate change disruption on people’s livelihood to recruit individuals.

Another alternative explanation is related to population growth, particularly the youth aspect. There is an increasing youth population who struggle to emancipate in rural societies in Mali, which are mostly managed by elders and aristocratic families. Some interviewees felt that the Dioros system restricts their ability to climb the ladder in rural areas and leave them with few other opportunities than working the land of their families. While this topic has been researched by several researchers in Mali (c.f Arnaud 2016), this an important factor that was not sufficiently explored in this study.

Climate change is one of the most pressing issues of our time (UN 2019) and it has a tangible negative effect on people’s livelihoods and natural resources. While the effects of climate change on conflict are mostly indirect in this instance, the breakdown of informal conflict resolution mechanisms is key for explaining the escalation of conflicts in central Mali. In many countries, impartial institutions both formal and informal can contemporaneously mitigate the negative effects of climate change on populations, but if drastic global action is not taken to curb greenhouse gases significantly, even functioning institutions may not be able to manage its overwhelming and unpredictable impacts.

Endnotes

[1] See Mach et al. 2019 for a more complete review.

[2] Academic Researcher 1, Bamako, 4 March 2019.

[3] Professor 3, Bamako, 22 January 2017.

[4] Academic Researcher 4, Bamako, 22 February 2019.

[5] Professor 1, Bamako, 4 March 2019.

[6] Local official 1, Tenenkou, 19 March 2019.

[7] Farmer 3, Tenenkou, 13 March 2019.

[8] Professor 5, Bamako, 27 January 2017

[9] Local Leader 6 (Farmers representative) Youwarou, 16 April 2019.

[10] Herder 6, Youwarou, 20 May 2019.

[11] Herder 2, Tenenkou, 22 March 2019.

[12] Herder 1, Tenenkou, 14 March 2019; Academic Researcher 2, Bamako, 3 March 2019.

[13] Academic Researcher 1, Bamako, 4 March 2019; Academic Researcher 3, Bamako, 21 March 2019.

[14] Herder 3, Tenenkou, 23 March 2019.

[15] Focus group 2 (representatives of Dogon community), Bamako, 29 January 2017.

[16] Local leader 4, Koro, 18 March 2019.

[17] This Peace agreement is available here: <https://www.hdcentre.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/Accord-de-paix-entre-les-communautés-Dogon-et-Peulh-du-cercle-deKoro-28-août-2018.pdf>

[18] NGO 1, Bamako, 30 February 2019.

[19] Local Leader 1, Bamako, 5 March 2019.

[20] Local leader 4 (village chief), Tenenkou, 18 March 2019.

[21] Military 2, Bamako, 24 January 2017.

[22] Professor 3, Bamako, 22 January 2017.

[23] Academic Researcher 3, Bamako, 21 March 2019.

[24] UN agency 1, Bamako, 18 January 2017.

[25] Local official 4, Tenenkou, 28 February 2019.

[26] Herder 6, Youwarou, 20 May 2019; Herder 3, Tenenkou, 23 March 2019.

[27] Professor 5, Bamako, 27 January 2017.

[28] Local Leader 1, Bamako, 5 March 2019.

[29] Farmer 1, Tenenkou, 17 March 2019; Local official 2, Tenenkou, 20 March 2019.

[30] School teacher 2, Youwarou, 17 April 2019.

[31] Local leader 4 (village chief), Tenenkou, 18 March 2019.

[32] Local leader 3, Tenenkou, 20 March 2019.

Sources

Ajayi, Adeyinka and Buhari, Lateef 2014. Methods of Conflict Resolution in African Traditional Society. African Research Review, 8(2) pp. 138–157.

Arnaud, Clara 2016 Les jeunes ruraux sahéliens, entre exclusion et insertion. Afrique Contemporaine, 3(259), pp. 133–136. Berman, Eli, Callen, Michael, Felter, Joseph., and Jacob Shapiro 2011. Do Working Men Rebel? Insurgency and Unemployment in Afghanistan, Iraq, and the Philippines. Journal of Conflict Resolution 55 (4), pp. 496–528.

Bogale, Ayalneh and Korf, Benedikt 2007. To share or not to share? (non-)violence, scarcity and resource access in Somali Region, Ethiopia. The Journal of Development Studies, 43(4), pp. 743–765.

Benjaminsen, Tor 2008. Does supply-induced scarcity drive violent conflict in the African Sahel? The case of the Tuareg rebellion in northern Mali. Journal of Peace Research, 45(6), pp. 819–836.

Benjaminsen, Tor A. and Ba, Boubacar 2019. Why do pastoralists in Mali join jihadist groups? A political ecological explanation. The Journal of Peasant Studies, 46(1), pp. 1–20.

Biernacki, Patrick and Waldorf, Dan 1981. Snowball sampling. Sociological Methods and Research, 10(02), pp.141–164.

Boone, Catherine 2014. Property and political order in Africa: Land rights and the structure of politics. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press.

Brosché, Johan, Elfverson, Emma 2012. Communal conflict, civil war and the state: Complexities, connections, and the case of Sudan. African Journal on Conflict Resolution, 12(1) pp. 9–32. Buhaug, Halvard 2015. Climate-conflict research: some reflections on the way forward. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Climate Change, 6(1), pp. 269–275.

Calzadilla, Alvaro, Katrin Rehdanz, Richard Betts, Pete Falloon, Andy Wiltshire, and Richard S. J. Tol. 2013. Climate Change Impacts on Global Agriculture. Climatic Change, 120 (1) pp. 357–74.

Cammett, Melanie 2006. Political ethnography in deeply divided societies. Qualitative Methods, 4(02), pp. 1–32.

Capoccia, Giovanni, Kelemen, Daniel 2007. The study of critical junctures: Theory, narrative, and counterfactuals in historical institutionalism. World politics, 59 (3), pp. 341–369.

Choudree, RBG 1999 Traditions of Conflict Resolution in South Africa. African Journal on Conflict Resolution 1(1), pp. 9–27.

Cohn, Avery S., Newton, Peter, Gil, Juliana D. B., Kuhl, Laura, Samberg, Leah, Ricciardi,

Vincent, Manly, Jessica R., Northrop, Sarah 2017. Smallholder Agriculture and Climate Change. Annual Review of Environment and Resources 42 (1), pp. 347–75.

Collier, Paul, and Anke Hoeffler 2004. Greed and Grievance in Civil War. Oxford Economic Papers 56 (4), pp. 563–95.

Cotula, Lorenzo. and Cissé, Salmana 2006. Changes in customary resource tenure systems in the inner Niger delta, Mali. Journal of Legal Pluralism and Unofficial Law 38 (52), pp. 1–29.

de Sherbinin, Andrea 2014. Climate change hotspots mapping: What have we learned? Climatic Change 123(1), pp. 23–37.

Detges, Adrien 2016. Local conditions of drought-related violence in sub-Saharan Africa: the role of road and water infrastructures. Journal Peace Research. 53 (5), pp. 696–710.

Eastin, Joshua 2018. Hell and high water: precipitation shocks and conflict violence in the Philippines. Political Geography. 63 (2), pp. 116–134.

Fjelde, Hanne and von Uexkull, Nina 2012. Climate triggers: Rainfall anomalies, vulnerability and communal conflict in Sub-Saharan Africa. Political Geography, 31(7), 444–453.

George, Alexander and Bennett, Andrew 2005. Case Studies and Theory Development in Social Sciences MIT Press.

Gerring, John and Jason Seawright 2007. Techniques for choosing cases. In: John Gerring (ed.) Case Study Research: Principles and Practices. New York, Cambridge University Press, pp. 294–308.

Grossman, Herschel 1991. A General Equilibrium Model of Insurrections. The American Economic Review 81 (4) pp. 912–21.

Helmke, Gretchen and Levitsky Steven 2004. Informal institutions and comparative politics: a research agenda. Perspective on Politics. 2 (4), pp. 725–740.

Husken, Thomas, Klute, Georg 2015. Political orders in the making: Emerging forms of political organization from Libya to Northern Mali. Africa Security, 8 (4), pp. 320–337.

Ibrahim, Yahaya and Zapata, Mollie 2018. Regions en danger: prevention d’atrocites de masse au Mali. Simon-Skjodt center for prevention of genocide. Available from: <https://www. ushmm.org/m/pdfs/Mali_Report_French_FINAL_April_2018.pdf>

ICG International Crisis Group (2019) Speaking with the “Bad Guys”: Toward dialogue with central Mali’s Jihadists. Africa Report, No276.

ICG International Crisis Group (2019) The Central Sahel: Scene of new climate wars? Crisis group Africa Briefing No 154.

ICG International Crisis Group (2020) Reversing Central Mali’s descent into communal violence. ICG Report, n 293, November 2020.

Jourde, Cédric, Brossier, Marie, Cissé, Modibi 2019. Prédation et violence au Mali : élites statutaires peules et logiques de domination dans la région de Mopti. Canadian Journal of African Studies 53(3) pp. 431–445.

Kalyvas, Stathis 2006. The Logic of Violence in Civil War. New York: Cambridge University Press. Koubi, Vally 2018. Exploring the relationship between climate change and violent conflict. Chinese Journal of Population Resources and Environment. 16 (3), pp. 197–202.

Krause, Jana 2019. Stabilization and Local Conflicts: Communal and Civil War in South Sudan, Ethnopolitics, 18 (5), pp. 478–493.

MacGinty, Roger 2008. Indigenous Peace-Making Versus the Liberal Peace. Cooperation and Conflict, 43 (2), pp. 139–163.

Mach, Kathrina J., Kraan, Caroline M., Adger Neil W. et al. 2019. Climate as a risk factor for armed conflict. Nature 571, pp. 193–197.

Maystadt, Jean-François; Ecker, Olivier 2014. Extreme weather and civil war: Does drought fuel conflict in Somalia through livestock Price shocks? American Journal of Agricultural Economics, 96 (4), pp. 1157–1182.

Menkhaus, Ken 2007. Governance without government in Somalia: spoilers, state building, and the politics of coping. International Security, 31(03), pp. 74 –106.

Mitra, S. 2017. Terrain fertile pour les conflits au Mali : changement climatique et surexploitation des resources. PlanetarySecurity Initiative, available at: <https://www.planetarysecurityinitiative.org/sites/default/files/2018-04/2.0%20Version%20-%20 Mali%20fertile%20grounds.pdf>

Mohammed, Ahmed, Beyene, Fekadu 2016. Social Capital and Pastoral Institutions in Conflict Management: Evidence from Eastern Ethiopia. Journal of International Development 28(1), pp. 74–88.

Ndubuisi, Christina 2017. Re-empowering indigenous principles for conflict resolution in Africa: Implication for the African Union. Africology: The Journal of Pan African Studies, 10 (9), pp. 15–35.

Ngaruiya, Grace W. and Scheffran, Jurgen 2016. Actors and Networks in Resource Conflict Resolution under Climate Change in Rural Kenya. Earth System Dynamics 7(2), pp. 441–452.

NUPI Norsk Utenrikspolitisk Institutt 2021. Mali: Climate, Peace and Security Fact sheet. May 2021. Available at: <https://www.nupi.no/nupi_eng/News/Climate-Peace-and-SecurityFact-Sheet-Mali>

Le Monde 2019. Dans le village peul attaqué au Mali: “ils ont tout brulé et tué tout ce qui bougeait encore” Available on: <https://www.lemonde.fr/afrique/article/2019/03/25/ massacre-a-ogossagou-au-centre-du-mali-ils-n-ont-epargne-personne-ils-ont-toutbrule_5440724_3212.html> Lieberman, Evan, and Singh, Prerna 2012. The Institutional Origins of Ethnic Violence. Comparative Politics. 45(1), pp. 1–24. Linke, Andrew M., O’Loughlin, John, McCabe, Terrence J., Tir, Jaroslav, Witmer, Frank D. 2018. Drought, local institutional contexts, and support for violence in Kenya. Journal of Conflict Resolution. 62 (7), pp. 1544–1578.

Linke, Andrew M., O’Loughlin, John, McCabe, Terrence J., Tir, Jaroslav, Witmer, Frank D. 2015. Rainfall variability and violence in rural Kenya: Investigating the effects of drought and the role of local institutions with survey data. Global Environmental Change. 33, pp. 35–47.

Logan, Carolyn 2013. The roots of resilience: Exploring popular support for African traditional authorities. African Affairs. 112 (448), pp. 353–376.

Hegre, Halvard and Nygard, Hegre 2015. Governance and Conflict Relapse. Journal of Conflict Resolution. 59 (6) pp. 984–1016.

Honig, Lauren 2017. Selecting the State or Choosing the Chief? The Political Determinants of Smallholder Land Titling. World Development. 100, pp. 94–107.

Ogbaharya, Daniel 2008. (Re-)building governance in post-conflict Africa: the role of the state and informal institutions. Development in Practice, 18(3) pp. 395–402.

Ostrom, Eleanor 1990. Governing the Commons: The Evolution of Institutions for Collective Action. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Raleigh, Clionadh 2010. Political marginalization, climate change, and conflict in African Sahel states. International Studies Review. 12 (1) pp. 69–86.

Roland, Gerard 2004. Understanding institutional change: Fast-moving and slow-moving institutions. Studies in Comparative International Development. 38(1), pp. 109–131.

Rothstein, Bo and Teorell, Jan 2008. What is quality of government? A theory of impartial institutions. Governance, 21 (2), pp.165–190.

Rothstein, Bo 2014. What is the opposite of corruption? Third World Quarterly, 35, pp. 888–904.

Rupiya, Martin 1999. Southern Africa in water crisis – A case study of the Pangara River Water shortage, 1987–1996. African Journal on Conflict Resolution, 1(1), pp. 1–28.

Sangare, Boukary 2016. Le centre du Mali: epicentre du djihadisme? Note d’analyse – 20 mai 2016, Groupe de Recherche et d’Information sur la Paix et la Sécurité. Availabe at: <http://www.grip.org/fr/node/2008>

Santer, Benjamin, Po-Chedley, Stephen. Zalinka, Mark, Cvijinovic, Ivana, Bonfils, Céline., Durack, Paul, Fu, Qiang., Kiehl, Jeffrey, Mears, Carl.; Painter, Jeffrey, Pallotta, Giuliana, Solomon, Susan. Wentz, Frank, Zou, Cheng 2018. Human influence on the seasonal cycle of tropospheric temperature. Science, 361(6399), pp. 8806.

SIPRI (2020) Pathways of climate insecurity: Guidance for policymakers. SIPRI Policy brief, November 2020. Available at: <https://www.sipri.org/publications/2020/sipri-policybriefs/pathways-climate-insecurity-guidance-policymakers>

SIPRI (2020) Achieving peace and developlment in Central Mali: Looking back o none year of SIPRI’s work. Available at: <https://www.sipri.org/commentary/ topical-backgrounder/2020/achieving-peace-and-development-central-mali-lookingback-one-year-sipris-work>

The Guardian (2020) Mali Killings: 40 die in inter-ethnic attacks, Saturday 15 February 2020. Available at: <https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/feb/15/mali-killings-40-die-ininter-ethnic-attacks>

Theisen, Ole M. 2017. Climate change and violence: Insights from political science. Current climate change reports, 3(4) pp. 210–221.

Turner, Michael 1999. The role of social networks, indefinite boundaries and political bargaining in maintaining the ecological and economic resilience of the transhumance systems of Sudano-Sahelian West Africa, in Niamir-Fuller, M. (ed) Managing mobility in African rangelands. The legitimization of transhumance. London: Intermediate Technology Publications.

UCDP 2020. Mali: Number of deaths, available at: <https://ucdp.uu.se/country/432>

United Nations 2019. “Climate change” available at: <https://www.un.org/en/sections/issuesdepth/climate-change/>

United Nations 2019. “Informal justice” available at: <https://www.un.org/ruleoflaw/thematicareas/access-to-justice-and-rule-of-law-institutions/informal-justice/>

Vesty, Jonas 2019. Climate variability and individual motivations for participating in political violence. Global Environmental Change, 56 (1), pp. 114–123.

von Uexkull, Nina, Croicu Mihail, Fjelde, Hanne, Buhaug. Halvard 2016. Civil Conflict Sensitivity to Growing-season Drought. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 113 (44), pp. 12391–96.

Walch, Colin 2018. Weakened by the storm: Rebel group recruitment in the wake of natural disasters in the Philippines. Journal of Peace Research 55(3), pp. 336–350.

Walch, Colin 2018. Disaster risk reduction amidst armed conflict: informal institutions, rebel groups, and wartime political orders. Disasters 4(1) pp. 239–264.

Wig, Tore, Kromrey, Daniela 2018. Which groups fight? Customary institutions and communal conflict in Africa. Journal of Peace Research, 55 (4), pp. 415–429.

Wig, Tore, Tollefsen, Andreas 2016. A Local Institutional Quality and Conflict Violence in Africa. Political Geography, 53 (7), pp. 30–42.

Wilfahrt, Martha 2018. Precolonial Legacies and Institutional Congruence in Public Goods Delivery: Evidence from Decentralized West Africa. World Politics 70(2), pp. 239–274.

Widmalm, Stein 2008. Decentralisation, Corruption and Social Capital: From India to the West. Thousand Oaks, Sage Publications.

Williams, Michael 2010. Chieftaincy, the state and democracy: Political Legitimacy in postapartheid South Africa. Bloomington, Indiana University Press.

Wischnath, Gerdis, Buhaug, Halvard 2014. Rice or riots: On food production and conflict severity across India. Political Geography, 43(0), pp. 6–15.

Wood, Elisabeth 2003. Insurgent Collective Action and Civil War in El Salvador. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press.