Introduction

“Going, going, gone!” is a refrain commonly used to herald the determination of the highest bidder of an item being sold on auction. This process of presenting items for bid, taking bids, and then selling them to the highest bidder aptly encapsulates a questionable practice that has permeated Nigeria’s recent electoral experience: vote buying. Vote buying is not fundamentally new to Nigeria’s electoral politics or only restricted to Nigeria or Africa.1 According to Matenga, however, “nearly 80% of voters from 36 African countries believe voters are bribed – either sometimes, often or always. Furthermore, 16% of voters in African countries reported being offered money or goods in exchange for their vote during the last election”.2

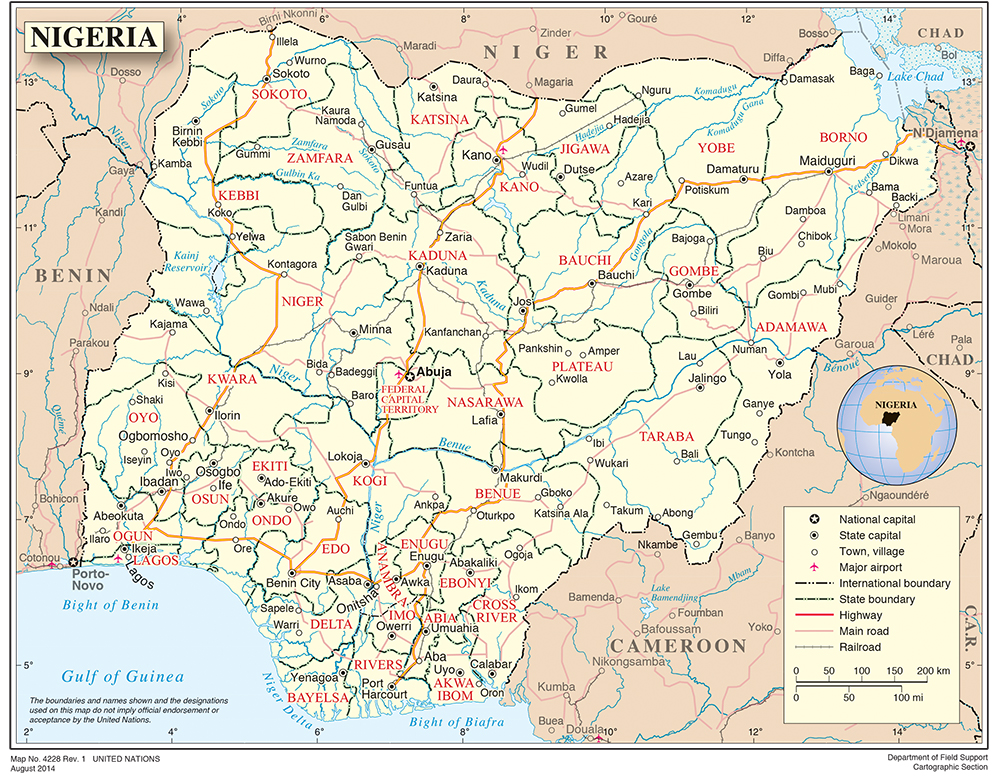

Since the return of democracy to Nigeria in May 1999, vote buying has steadily grown in scale and brazenness. Several videos and images have emerged, showing unabashed sharing of cash, food and valuable items among the electorate by politicians and parties during recent elections in Edo, Anambra, Ondo and Ekiti states. This has led to the apt description of Nigeria’s electoral politics as “cash-and-carry democracy”. If not urgently addressed, this trend portends grave danger for Nigeria’s democracy. This article therefore highlights the nature, causes and implications of vote buying for democratic governance in Nigeria.

Conceptual Clarifications

The past decade has witnessed an explosion in the use of the term “vote buying” in academic and media circles. An often-cited definition of vote buying describes it as “the exchange of private material benefits for political support”.3 Vote buying is seen as a contract, or perhaps an auction in which the voter sells his or her vote to the highest bidder.4 Vote buying is defined here as any form of financial, material or promissory inducement or reward by a candidate, political party, agent or supporter to influence a voter to cast his or her vote or even abstain from doing so in order to enhance the chances of a particular contestant to win an election. Thus, any practice of immediate or promised reward to a person for voting or refraining from voting in a particular way can be regarded as vote buying. In most democracies, vote buying is considered an electoral offence.

Criminalisation of Vote Buying in Nigeria

Vote buying is prohibited in Nigeria. Article 130 of the Electoral Act 2010, as amended, states that:

A person who — (a) corruptly by himself or by any other person at any time after the date of an election has been announced, directly or indirectly gives or provides or pays money to or for any person for the purpose of corruptly influencing that person or any other person to vote or refrain from voting at such election, or on account of such person or any other person having voted or refrained from voting at such election; or (b) being a voter, corruptly accepts or takes money or any other inducement during any of the period stated in paragraph (a) of this section, commits an offence and is liable on conviction to a fine of N100,000 or 12 months imprisonment or both.5

Similarly, the 2018 Revised Code of Conduct for Political Parties in section VIII (e) provides that, ”… all political parties and their agents shall not engage in the following practice: buying of votes or offer any bribe, gift, reward, gratification or any other monetary or material considerations or allurement to voters and electoral officials”.6 Notwithstanding its prohibition, vote buying continues to be a widespread practice in Nigeria’s recent elections.

Nature and Manifestation of Vote Buying in Recent Elections in Nigeria

Although vote buying has become ubiquitous in recent elections, its history predates the return to democracy in May 1999. There have been allegations of vote buying in the electoral history of Nigeria. It was rife during the Social Democratic Party presidential primary in Jos in 1992. Indeed, vote buying was part of the reason adduced by Ibrahim Badamasi Babangida for annulling the 12 June 1993 presidential poll which was hailed as the freest and fairest election in Nigeria’s history:

Even before the presidential election, and indeed at the party conventions, we had full knowledge of the bad signals pertaining to the enormous breach of the rules and regulations of democratic elections…. There were proofs as well as documented evidence of widespread use of money during the party primaries as well as the presidential election.… Evidence available to government put the total amount of money spent by the presidential candidates at over two billion, one hundred million naira (N2.1 billion). The use of money was again the major source of undermining the electoral process.7

Vote buying has been an integral element of money politics in Nigeria. Recent experiences however show that vote buying takes place at multiple stages of the electoral cycle and has been observed eminently during voter registration, the nomination period, campaigning and election day.8 It is more predominant during election day, shortly before or during vote casting.

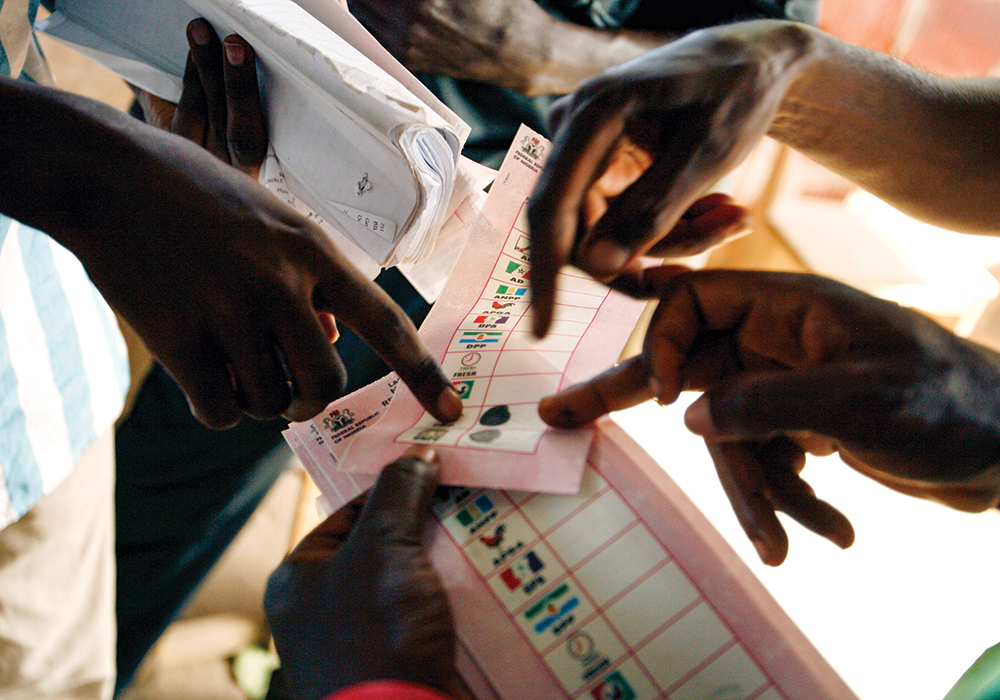

Like a typical market place, the politicians, political parties, and party agents are the vote buyers while prospective voters are the sellers. The commodity on sale is the vote to be cast while the medium of exchange could be monetary and non-monetary items. The market force that determines the value or price of a vote is the level of desperation of politicians to win in a locality. Although money and other valuables can be used to effectuate vote buying, political actors have adopted two main approaches to buying votes for election day.

The first is the Cash for Vote approach. It involves giving or promising the prospective voter some agreed amount of money well before the individual casts his or her vote at the polling station. The payment is done before the actual voting, and could be within the vicinity of the polling station or farther away. The ”settlement” is made secretly or in the open. Often, the vote buyers demand evidence of ownership of a voter’s card and assurance that the voter will vote for their party before offering the money.9 In this approach, trust is key to the contract. It is also known as the pre-paid method of vote buying.

The second approach is the Vote for Cash. It involves giving or rewarding the voter with the agreed amount of money or material compensation after the individual has shown evidence that he or she voted for the party. There are several ways the voter can prove to the vote buyer that he or she voted for the agreed candidate. One method is where the voter shrewdly displays the ballot paper that (s)he has thumb printed in favour of a particular party, so that the party agent standing strategically nearby can confirm compliance with the unholy contract as (s)he emerges from the cubicle at the polling station.10 Another method is for the voter to photograph the thumb printed ballot paper to show as evidence. Thereafter, compensation in cash and/or kind can occur either immediately or at the close of balloting, and may take place within the precinct of the polling station or at an agreed place. In this approach, evidence is key to the consummation of the contract. This approach is also known as the “see and buy” or the post-paid method.

The vote buying practice, which is completely antithetical to the ethos and norms of democracy, has become a common feature of party primaries and general elections conducted in recent years in Nigeria. For example, during the All Progressive Congress (APC) presidential primary in Lagos State before the 2015 elections, it was reported that “over 8 000 delegates who participated allegedly made US$5 000 each from the candidates. Delegates were supposed to have received US$2 000 each from the Atiku Abubakar group and also US$3 000 each from the Buhari group. Given that more than 8 000 delegates were reported to have attended the primaries, the competing camps could have spent more than US$16 million and US$24 million respectively on vote buying at the primary stage”.11

There were widespread allegations of vote buying in the off-cycle governorship elections in Edo and Ondo states in 2016. In the 28 September 2016 gubernatorial election in Edo, observers reported massive vote buying by the two main political parties, the APC and the Peoples Democratic Party (PDP). The parties were accused of giving N3 000 to N4 000 for votes in several polling units.12 Similarly, in the 26 November 2016 governorship election in Ondo State, it was observed that members of the APC, the PDP and the Alliance for Democracy were giving money to voters at most polling centres across the state. Some polling stations in Odigbo, Okitipupa and Ilaje local government areas were given N450 000 while each voter got between N3 000 and N5 000”.13

In the 18 November 2017 gubernatorial election in Anambra State, many observers condemned the brazen incidences of vote buying during the poll, stating that the level of commercialisation of the vote was an eyesore to democracy.14 In particular, the Nigeria Civil Society Situation Room noted that “even more lamentable was the fact that the buying and selling of votes took place in the full glare of security men and election officials. It was simply a bazaar in which the election officials and security agencies were undoubtedly complicit”.15

Widespread acts of vote-buying were also reported during the recently held governorship election in Ekiti State on 14 July 2018. For example, the Punch newspaper documented the case of a retiree who claimed that an APC agent offered him money to vote for the party. According to the septuagenarian:

I was offered N5,000 to vote for the party but I rejected it. I am 73 years old retired teacher. I cannot allow the future of my children to be bought by moneybags. I don’t know how we descended to this level when people brazenly offer money to people to secure their votes. It was not like this in the past. Will our votes count with this problem?16

Kayode Fayemi, of President Muhammadu Buhari’s APC won the governorship election, polling 197 459 votes while Kolapo Olusola scored 178 114 votes. Both the APC and the PDP were alleged to have paid voters N3 000 to N 5 000 each.17 The impunity of vote-buying is becoming the norm in Nigeria’s electoral politics with political parties trying to outwit each other in the amounts paid to voters.

Factors Behind Vote Buying

Several factors contribute to the rise in vote buying. Top on the list is recent technological innovations such as the introduction of handheld devices to read biometric voter identity cards and electronic tracking of electoral materials, which has vastly reduced traditional forms of rigging. Hence, politicians have come to realise that falsification of election results in order to emerge winners is becoming counter-productive, especially as the judiciary has also annulled many rigged elections. They have therefore resorted to wooing voters with money, foodstuffs, clothes and other souvenirs in exchange for their votes.

The desperation of politicians who want to win elections at all costs is another factor. Politicians engage in vote buying because of the promise of enormous power and wealth they hope to gain once they enter government. There is also the fear among many politicians that if they do not engage in the act, their opponents will still do so and gain electoral advantage. This dilemma has thus made vote buying a race of sorts especially among the “big” political parties.

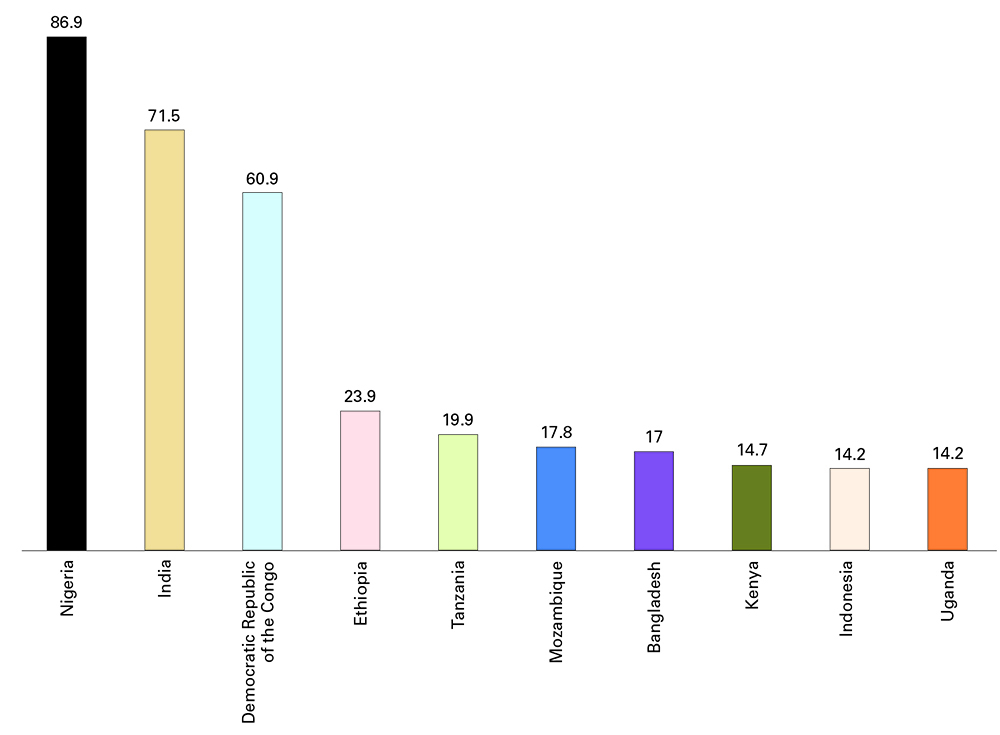

A third factor is the high incidence of poverty in the country. Nigeria has the largest extreme poverty population in the world as at June 2018 (see Figure 1), with over 87 million or nearly 50% of its estimated 180 million population living below the poverty line.18 Poverty is particularly acute in rural areas and among female-headed households, making many people susceptible to selling their vote for immediate gratification.

Figure 1: Largest Extreme Poverty Population in the World as of June 2018 (in Millions)19

Another factor that has contributed to vote buying is the existence of security votes. Security votes are monthly allowances that are allocated to the 36 states within the Federal Republic of Nigeria for the sole purpose of funding security services within such states.20 However, the failure to subject the funding to legislative oversight or independent audit allowed successive presidents and state governors to treat it as a slush fund and direct it to political activities, such as buying votes during elections. In fact, lack of robust auditing and accountability mechanisms has meant that some incumbents embezzle the funds outright.21

Complacency and complicity of security agents and election officials add to the problem. In order to seal their protection and loyalty, security agents are usually the first to be compromised by the political parties or candidates. Hence vote trading often takes place in the presence of security agents who appear unable or unwilling or too compromised to deter such electoral offences. There is also the related problem of the weakness of the rule of law. The fact that those who engage in the act are never arrested and prosecuted encourages many others to adopt the strategy.

Consequences of Vote Buying

The consequences of vote buying are manifold. In the first instance, it unduly raises the cost of elections thereby shutting out contestants with little finances and promoting political corruption. When victory is purchased rather than won fairly, it obviously leads to state capture. It equally compromises the credibility, legitimacy and integrity of elections. Vote buying undermines the integrity of elections as the winners are often the highest bidders and not necessarily the most popular or credible contestants.22 It therefore discourages conscientious people from participating in electoral politics and causes citizens to lose faith in state institutions.

Vote trading equally has the tendency to perpetuate bad governance. It not only compromises the wellbeing of those who sold their vote for instant gratification, but also the future of those who did not sell their votes but are inevitably exposed to bad governance that results from such a fraudulent process. For every vote traded, there are many people who will suffer the unintended consequences when the traded votes make the difference between winning and losing in the election.

Recommendations

In view of the dangers vote buying poses to democracy in Nigeria, the following recommendations are proffered:

- The Independent National Electoral Commission (INEC) and the Economic and Financial Crimes Commission (EFCC) should develop a strategic collaborative framework for effective monitoring of political parties’ campaign funds in order to effectively curb electoral fraud, including vote buying.

- To enhance the secrecy of the ballot, the INEC should construct a collapsible voting cubicle that will make it difficult for party agents to see a voter thumbprint on the ballot paper. Actions that reveal the vote cast by voters should be criminalised.

- Civil society groups should advocate and apply pressure for police and other law enforcement agencies to arrest, investigate and diligently prosecute those involved in the act of vote trading.

- The National Assembly should fast-track deliberation and passage of the Bill establishing the National Electoral Offences Commission (NEOC) ahead of the 2019 general election. The NEOC, when established, should be well resourced to perform its statutory functions of arresting, investigating and prosecuting electoral offenders.

- Media and civil society organisations need to intensify voter education and enlightenment campaigns on the negative implications of vote trading– particularly on how it raises the costs of elections, promotes political corruption and undermines good governance.

- The Electoral Act should be amended to: empower citizens to effectively deploy social media tools in facilitating exposure of electoral fraud like vote buying, and prohibit the photographing of ballot papers by a voter or any person.

- The Nigerian government should pursue a policy of aggressive diversification of the economy to create more employment opportunities and reduce the level of poverty that makes people susceptible to criminal, financial and material inducements.

Conclusion

The ignoble trade in votes that followed the gubernatorial elections in Edo, Ondo, Anambra, and recently Ekiti states in the recent past clearly indicates that democracy in Nigeria is on sale in an open market. What is particularly worrisome is the brazen nature vote buying has assumed in recent times and the grave danger it poses to democracy. As the 2019 general elections draw near, the future of genuine democratic rule will hugely depend on how the various stakeholders – politicians, electorates, government officials, political parties, civil society organisations, and the media – work assiduously to roll back the tide of vote buying. Saving Nigeria’s budding democracy from collapsing into a moneyocracy under the weight of vote buying is a task that must be urgently undertaken.

Endnotes

- Schaffer, F. Charles (2007) Elections for Sale: The Causes and Consequences of Vote Buying. London: Lynne Rienner.

- Matenga, Gram (2016) Cash for Votes: Political Legitimacy in Nigeria, Available at: <https://www.opendemocracy.net/gram-matenga/cash-for-votes-political-legitimacy-in-nigeria> [Accessed 14 July 2018].

- Etzioni-Halevy, Eva (1989) “Exchange Material Benefits for Political Support: A Comparative Analysis”, Dalam Heidenheimer, et al. (eds). Political Corruption: A Handbook. Page 287–304. New Jersey: Transaction Publishers. p. 287.

- Schaffer, Charles (2002) What is Vote Buying? Paper prepared for presentation at International Conference on “Trading Political Rights: The Comparative Politics of Vote Buying,” Centre for International Studies, MIT, Cambridge.

- The Electoral Act 2010 (as amended), Available at: <https://nass.gov.ng/document/download/5804> [Accessed 4 June 2018].

- The Independent Electoral Commission (2013), Code of Conduct for Political Parties. Available at: <http://www.inecnigeria.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/03/Code_of_Conduct_For_Political_Parties_Preamble.pdf> [Accessed 4 June 2018].

- Ajani, Jide (2013) Why we Annulled June 12 Presidential election – General Ibrahim Babangida, Available at: <https://www.vanguardngr.com/2013/06/why-we-annuled-june-12-presidential-election-general-ibrahim-babangida/> [Accessed 8 June 2018].

- Matenga, Gram (2016) op. cit.

- Atoyebi, Olufemi; Ajaja, Tunde and Aworinde, Tobi (2018) Fayemi wins as APC, PDP woo voters with cash, Available at: <http://punchng.com/fayemi-wins-as-apc-pdp-woo-voters-with-cash/> [Accessed 21 July 2018].

- Tribune, (2018) Overcoming Vote Buying, Available at: <http://www.tribuneonlineng.com/overcoming-vote-buying/> [Accessed 3 March 2018].

- Matenga, Gram (2016) op. cit.

- The Whistler, (2016) #EdoDecides: APC, PDP In Vote Buying, Interstate TravelersTrapped, Available at: <https://thewhistler.ng/story/edodecides-apc-pdp-in-vote-buying-interstate-travelers-trapped/> [Accessed 20 July 2018].

- Dada, Peter (2016) Vote Buying Allegations Trail Ondo Election, Available at: <http://www.punchng.com/vote-buying-allegations-trail-ondo-election/> [Accessed 3 February 2018].

- Vanguard, (2017) Anambra Poll and the Evil of Vote-Buying, Available at: <https://www.vanguardngr.com/2017/11/anambra-poll-evil-vote-buying/> [Accessed 3 February 2018].

- Ibid.

- Atoyebi, Olufemi; Ajaja, Tunde and Aworinde, Tobi (2018) op. cit.

- AFP, (2018) Cash-for-votes Fears before Nigerian General Election. Available at: <https://guardian.ng/politics/cash-for-votes-fears-before-nigerian-general-election/> [Accessed 21 July 2018].

- Punch, (2018) With 87m poor citizens, Nigeria overtakes India as World’s Poverty Capital, Available at: <http://punchng.com/with-87m-poor-citizens-nigeria-overtakes-india-as-worlds-poverty-capital/> [Accessed 29 June 2018].

- Kharas, Homi; Hamel, Kristofer and Hofer, Martin (2018) ‘The Start of a New Poverty Narrative, Available at: <https://www.brookings.edu/blog/future-development/2018/06/19/the-start-of-a-new-poverty-narrative/> [Accessed 25 July 2018].

- Egbo, Obiamaka; Nwakoby, Ifeoma; Onwumere, Josaphat and Uche, Chibuike (2012) Security Votes in Nigeria: Disguising Stealing from the Public Purse, African Affairs, 111(445): 597–614.

- For further insight, see Page, Mathew. (2018) Camouflaged Cash: How ‘Security Votes’ Fuel Corruption in Nigeria. London: Transparency International.

- Adamu, Abdulrahman; Ocheni, Danladi and Ibrahim, Sani (2016) Money Politics and Analysis of Voting Behaviour in Nigeria: Challenges and Prospects for Free and Fair Elections. International Journal of Public Administration and Management Research, 3(3):89–99.