The nature of conflict and contestation in Africa has evolved drastically over the last five years. While conflict remains a major threat to children, the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 significantly compounded their vulnerability by introducing additional complexities in already fragile contexts. We have since entered a chapter of increased geopolitical conflict, and not in Africa alone. There have been ongoing conflicts in Ukraine and Israel, as well as global economic turmoil. Each of these threats has had dire consequences for the agenda for peace, none as significant as on the plight of children, especially children in fragile and conflict-affected areas in Africa.

This article explores the circumstances facing children living in conflict-affected areas across Africa. It assesses the response and effectiveness of international bodies, such as the United Nations (UN) and the African Union (AU), in safeguarding the future of the continent’s youngest and most vulnerable group.

Global dynamics and the impact on child welfare

The COVID-19 pandemic itself has had a profound impact on child welfare globally, exacerbating their vulnerabilities and highlighting the urgent need for comprehensive support systems tailored to children’s needs. The impact of the pandemic on the economy alone in 2020 resulted in job losses, income decrement, adverse mental health effects, and limited access to essential health services for all spheres of society, including women and young people. This has had an effect on children, making them more exposed and susceptible to health and mental disorders as well as socio-economic problems. Of course, some children’s needs were met by countries with existing infrastructure and resources to respond accordingly; however, for conflict-affected countries that have limited infrastructure and weak state institutions, this had an adverse effect on peace and development. For instance, in Libya during the global pandemic, armed groups, the Libyan National Army (LNA) and the Government of National Accord (GNA), seized the opportunity to intensify their war efforts and fighting, shelling neighbourhoods in and around Tripoli, despite the UN’s calls for a ceasefire. The ongoing political crisis, coupled with the socio-economic and political impact of COVID-19 during 2020, saw over 1.2 million people in need of humanitarian aid, of which 30% were children.1 The threats expanded beyond the conflict, disrupting immunisation programmes for children and creating the risk of outbreaks of vaccine-preventable diseases.2

The state of children in Africa

In Africa, the plight of many children has worsened due to the direct and indirect impact of ongoing conflicts and global instability. Yet there is a need to contextualise the experience of children across the 55 sovereign states in Africa. For instance, a child who is born in the Central African Republic (CAR) faces grave risks during their infancy, but this is rarely the case for a child who is born in Rwanda. This is because the CAR has experienced decades of instability and conflict, and access to healthcare for pregnant women and newborns is among the most undeveloped in the world.3 In Rwanda, by contrast, 91% of deliveries take place in a healthcare facility, thus giving a newborn child a better chance of survival.4 Disparities become more pronounced in African states experiencing conflict, and where human rights atrocities are committed against children.

The protracted crises in the Sudan and South Sudan region further illustrate this reality. Since South Sudan’s independence in 2011, it has been reported that over 70% of newborn children have been born into conflict situations. In Sudan, ongoing conflict since 2023 has severely affected the survival of children, with 14 million in need of humanitarian aid and 3.5 million under five years being acutely malnourished. These alarming developments prompt deeper reflection on the plight of children in the region beyond recent issues and raise serious concerns about the role of governments and international bodies in the protection and advancement of children’s lives and development.5

In West Africa, June 2024 marked a decade since the abduction of 276 schoolgirls by Boko Haram in Chibok, Nigeria, of which 96 remained in captivity. Since the 2014 Nigeria crisis, more than 1 680 school children between the ages of five and 11 years have been abducted in the country.6 Terrorist organisations use the mass abduction of children as a tool of war and to assert dominance over the government. It has become evident that placing children at the centre of conflict resolution and peace is imperative for the sustainable development of any nation.

The 2025 UN Report on Children and Armed Conflict (CAAC) revealed that one in six children globally lives in a conflict zone.7 The report further noted that verified violations against children reached an all-time high of 41,370 in 2024, with the killing and maiming of children at the highest, followed by the denial of humanitarian access, and the abduction of children.8 While non-state armed groups were identified as the main perpetrators of these violations, state forces also played a prominent role in exacerbating and perpetuating the grave violations against children. For this reason the UN Special Representative on CAAC has opted to establish strong partnerships with regional and subregional entities, such as the AU, to establish comprehensive mechanisms that are context specific for the well-being and welfare of children.

The UN and child protection in Africa

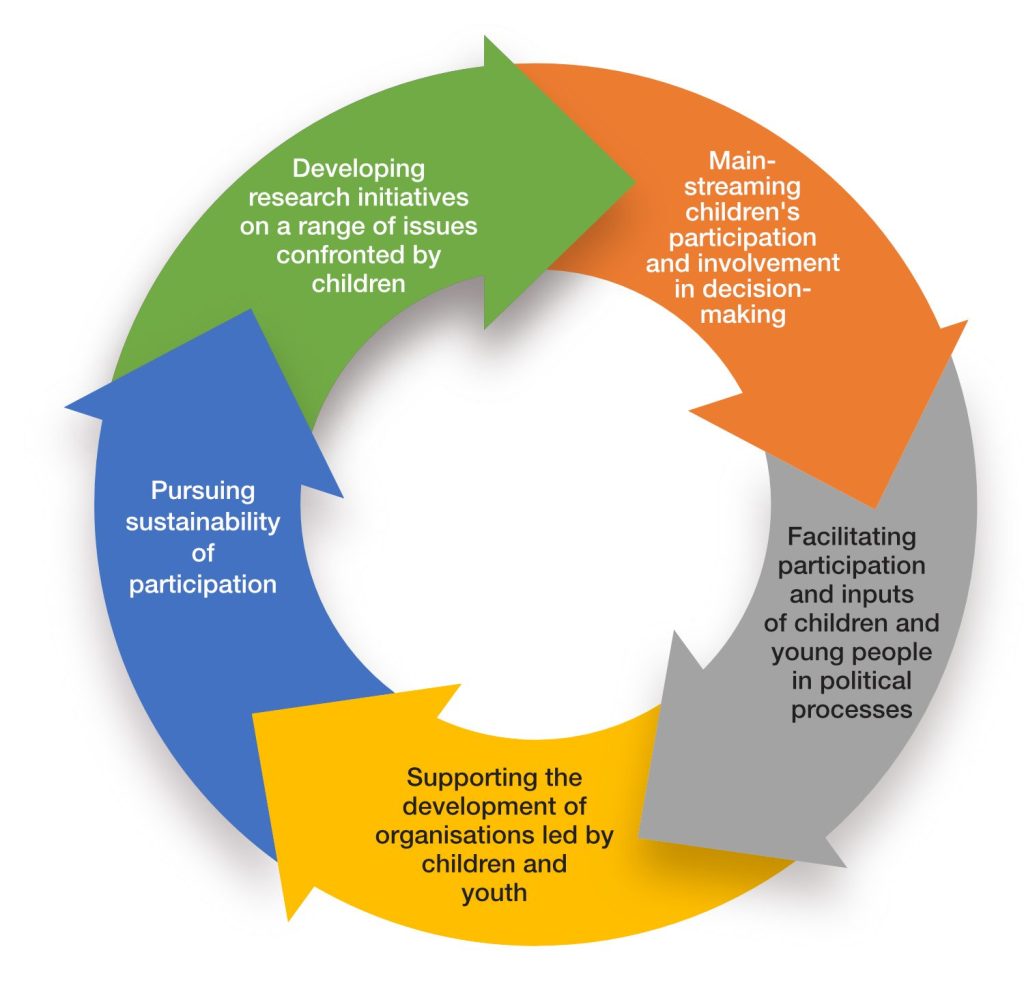

In 1996, the UN released the Machel Report on the Impact of Armed Conflict on Children, in which Graça Machel warned of growing conflict and the impact of atrocities and violations against children. In the report, Machel referred to the world being ‘sucked into a desolate moral vacuum,’ where atrocities against children would become normalised and more violent, due to the changing nature of conflict.9 Her findings and the report have proven to be well-founded. As a result of the recommendations of the report, the UN General Assembly established the ‘A World Fit for Children’ strategy. The Office of the Special Representative of the Secretary General (SRSG) for Children and Armed Conflict was also established based on Machel’s recommendations. The SRSG produces an annual report with recommendations on the state of children in armed conflicts.10 At the international and national levels, efforts have increased to encourage children to share their experiences, challenges, aspirations and knowledge for research, monitoring and evaluation to understand better and strengthen the impact of the global response to humanitarian issues. In addition, the UN Security Council (UNSC), through Resolution 1261, established a working group focused on integrating the protection of children into its work. Following the 10-year strategic review of the Machel Report in 2009, the UN General Assembly agreed to prioritise specific actions for children, as shown in Figure 1.11

Figure 1: Recommendations on the protection of children from the Machel Study 10-Year Strategic Review

The UN’s adoption of a systematic approach to child protection since 1996 has created more strategic and comprehensive efforts globally that seek to engage and work alongside institutions in child protection. For example, the Government of CAR, through close collaboration with the UN International Children’s Emergency Fund (UNICEF), developed the Child Protection Code in 2020 to strengthen its national legal framework. As a result, the UN has managed to negotiate for the release of 653 children from the control of armed forces, all of whom benefited from reintegration support.12 In the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), the UN has supported government efforts to screen and prevent the recruitment and enlistment of children and young people into security and armed forces. Thus far, 162 children have been released by armed groups.13 In Mali, the UN has worked closely with the national defence and security forces to establish a framework that addresses child protection and grave violations.14

The AU and child protection in Africa

In collaboration with the UN, African efforts have also played a role in protecting children and preventing the enactment of violence. More specifically, in 2022, the AU adopted the policy on Child Protection in AU Peace Support Operations (PSOs) and the Policy on Mainstreaming Child Protection into the African Peace and Security Architecture (APSA).15 The adoption of the policies was primarily due to the enduring challenges of protecting children in conflict-affected areas, and where PSOs are deployed. Currently, it has become mandatory to apply the Child Protection Policy in PSOs that are mandated, authorised, endorsed or recognised by the AU.16

However, there has been a rise in the deployment of missions that are not fully mandated, authorised, endorsed or recognised by the AU Peace and Security Council (PSC). Such circumstances have raised questions on the compliance of such missions with international legal frameworks and regional standards and norms to protect civilians, specifically international humanitarian law/international human rights law (IHL/IHRL). To address and counter such matters, the AU established the Africa Platform on Children Affected by Armed Conflicts (AP-CAAC), a high-level advocacy mechanism that offers support and advisory services to enhance child protection in ad hoc missions and member states. In 2022, the AP-CAAC undertook a solidarity mission to Mozambique to identify ways to support the efforts of the Government of Mozambique and other stakeholders to promote the welfare of children affected by armed conflicts. 17

Furthermore, through the AU Commission’s Political Affairs, Peace and Security (PAPS) Department, capacity-building training on child protection has been conducted across Africa, and training centres of excellence to enhance the African Standby Force (ASF) have been opened. Since 2022, more efforts have been made to execute in-mission training, such as in Somalia. Due to the AU Transitional Mission in Somalia (ATMIS) exit strategy and the drawdown of forces, more efforts have been made to train ATMIS police personnel, the Somali Police Force (SPF) and the Somali Security Forces (SSF) in child protection, which includes understanding the national and international legal frameworks on human rights and humanitarian law.18 These child protection efforts of the AU are captured in Figure 2.

Figure 2: Child protection efforts by the AU

Despite the significant progress made by the AU, there are challenges which need to be addressed to enhance the promotion of the rights and welfare of children in conflicts. These challenges include limited resources, the low implementation rate of decisions of key policy organs, and a lack of accountability for perpetrators.

Conclusion

More than 29 years since the Machel Report was published, the UN and AU have made strides to consolidate their efforts with partner institutions, governments, civil society and international organisations to better prevent and respond to grave violations against children in the context of armed conflicts. Yet, gaps in coordination, resource allocation, and policy implementation persist. In 2023, during the international conference on protecting children in armed conflict held in Norway, the Norwegian Government pledged NOK 1 billion (USD 93.7 million) for three years in efforts to support the fight to protect children in armed conflicts.19 Such a commitment addresses the challenges of limited resources and further seeks to enhance the efforts of the UN, AU, international institutions and humanitarian operations in child protection.

As conflicts in Africa continue to evolve and present new challenges, it is imperative for the UN, AU, and their partner institutions to enhance their collaborative efforts and adapt strategies to protect children in armed conflicts more effectively. The dynamic nature of contemporary conflicts demands that these bodies not only share lessons learnt but also coordinate their efforts to create a more comprehensive and responsive approach for child protection.

It would further be in the interest of PSOs, bi/multilateral missions and ad hoc coalitions if engagements were to be held on how to best utilise and harmonise existing resources, developed capacities, and the ASF framework to enhance peace and security, and child protection. A study may need to be considered in the near future to examine the effectiveness and impact of the Child Protection Policy in PSOs, more specifically in AU-mandated, authorised, endorsed or recognised PSOs. This should further apply to bi/multilateral missions and ad hoc coalitions, to ensure compliance in the Protection of Civilians, including child protection. This may necessitate increased coordination and cooperation between the UN, AU, regional institutions, partner institutions, governments, civil society and international organisations in capacity building, policy-making and developing strategies to improve the state of children, particularly those in armed conflicts. Moreover, the recently formed AP-CAAC can serve as a champion and advocate of initiatives that seek to secure the protection of children in armed conflicts.

Wandile Langa is a Programme Officer within ACCORD’s Peace Support Operations Unit. Wandile holds a Master of Social Science degree in Political Science from the University of KwaZulu-Natal, where he also obtained his Bachelor of Social Science Honours degree in International Relations. His other qualifications include a Postgraduate Diploma in International Studies from Rhodes University, and a Bachelor of Administration degree in Industrial Psychology from the University of Zululand.

Endnotes

1UNICEF (2021) ‘Humanitarian Action for Children’, Available at: https://www.unicef.org/media/87136/file/2021-HAC-Libya.pdf [Date accessed: 11 June 2025].

2UNICEF (2023) ‘Libya Annual Report’, Available at: https://www.unicef.org/mena/media/24636/file/UNICEF%20Libya%20Annual%20Report%202023.pdf [Date accessed: 11 June 2025].

3Médecins Sans Frontières (2025) ‘Gaza: Luxembourg must strengthen its commitment by welcoming more medical evacuations’, Available at: https://msf.lu/en/news/testimonies/to-be-born-or-to-give-birth-is-to-take-a-risk [Date accessed: 17 July 2025].

4Nishimwe, A.; Conco, D. N.; Nyssen, M.; and Ibisomi, L. (2022) ‘Context specific realities and experiences of nurses and midwives in basic emergency obstetric and newborn care services in two district hospitals in Rwanda: a qualitative study’, BMC Nursing, 21(1): 1–16. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12912-021-00793-y

5Human Sciences Research Council (2024) ‘International and regional interventions should protect children affected by armed conflict in South Sudan during handover: gaps and silences’, Available at: https://hsrc.ac.za/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/PB_International-and-regional-interventions-should-protect-children.pdf [Date accessed: 19 July 2025]; UNICEF (2018) ‘3 in 4 children born in South Sudan since independence have known nothing but war – UNICEF’, Available at: https://www.unicef.org/press-releases/children-born-south-sudan-independence-nothing-war [Date accessed: 18 July 2025].

6Ogunade, F. (2025) ‘Nigeria’s schoolchildren once again the target of mass abductions’, Enhancing Africa’s ability to Counter Transnational Crime (ENACT) Observer, Available at: https://enactafrica.org/enact-observer/nigeria-s-schoolchildren-once-again-the-target-of-mass-abductions [Date accessed: 5 August 2025].

7UNICEF (2024) ‘“Not the new normal” – 2024 “one of the worst years in UNICEF’s history” for children in conflict’, Available at: https://www.unicef.org/press-releases/not-new-normal-2024-one-worst-years-unicefs-history-children-conflict [Date accessed: 10 August 2025].

8UN (2025) ‘Children and armed conflict: Report of the Special Representative of the Secretary-General for Children and Armed Conflict’, Ref: A/80/266, Available at: https://docs.un.org/en/A/80/266 [Date accessed: 28 September 2025].

9Machel, G. (1996) ‘Impact of Armed Conflict on Children, Note by the Secretary General’, UN Report, Ref: A/51/306, Available at: https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/223213?v=pdf [Date accessed: 28 September 2025], p. 9.

10Ibid.

11UNICEF (2009) ‘Machel Study 10-Year Strategic Review: Children and Conflict in a Changing World’, Available at: https://childrenandarmedconflict.un.org/publications/MachelStudy-10YearStrategicReview_en.pdf [Date accessed: 15 May 2025].

12UNICEF Communication (2022) ‘Protecting Children in the Central African Republic’, Available at: https://www.unicef.org/wca/press-releases/protecting-children-central-african-republic [Date accessed: 20 May 2025].

13UN General Assembly (2022) ‘Report of the Special Representative of the Secretary General for Children and Armed Conflict’, Ref: A/77/143, Available at: https://documents-dds-ny.un.org/doc/UNDOC/GEN/N22/441/10/PDF/N2244110.pdf?OpenElement [Date accessed: 15 September 2025].

14Ibid.

15AU PSC (2022) ‘PSC Communique of the 1070th meeting of the PSC held on 29 March 2022 the update on the policies on child protection in African Union Peace Support Operations (AU PSOs) and mainstreaming child protection in the African Peace and Security Architecture (APSA)’, Available at: https://www.peaceau.org/en/article/communique-adopted-by-the-psc-of-the-au-at-its-1070th-meeting-held-on-29-march-2022-on-the-update-on-the-policies-on-child-protection-in-african-union-peace-support-operations-au-psos-and-mainstreaming-child-protection-in-the-african-peace-and-security [Date accessed: 1 October 2025].

16AU (2021) ‘Draft Policy on Child Protection in African Union Peace Support Operations’, Available at: https://portal.africa-union.org/DVD/Documents/DOC-AU-WD/EX%20CL%201395%20(XLII)%20Annex%201%20_E.pdf [Date accessed: 10 October 2025].

17Wairoba, I. M. (2022) ‘The Africa Platform on Children Affected by Armed Conflicts Undertakes a Solidarity Mission to Mozambique to Advocate for the Rights of Children in Conflict Situations’, Available at: https://www.peaceau.org/en/article/the-africa-platform-on-children-affected-by-armed-conflicts-calls-on-mozambique-to-strengthen-national-efforts-aimed-at-protecting-children-in-situations-of-conflict [Date accessed: 10 October 2025].

18ATMIS News (2022) ‘SPF officers undertake training on Sexual, Gender-Based Violence and Child Protection to protect women and children’, Available at: https://atmis-au.org/spf-officers-undertake-training-on-sexual-gender-based-violence-and-child-protection-to-protect-women-and-children [Date accessed: 15 October 2025]. See also: Dalsan TV (2023) ‘ATMIS officers building capacities to enhance child protection in Somalia’ [Online video], Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EGIdIPGCXcU [Date accessed: 15 October 2025]; ATMIS (2023) ‘ATMIS has concluded a Training of Trainers course on Child Protection’, 28 May, Available at: https://x.com/ATMIS_Somalia/status/1662892025019002880?s=20 [Date accessed: 1 October 2025].

19Norwegian Ministry of Foreign Affairs (2023) ‘Norway pledges NOK 1 billion for protection of children in armed conflict’, Available at: https://www.regjeringen.no/en/whats-new/norway-pledges-nok-1-billion-for-protection-of-children-in-armed-conflict/id2982954 [Date accessed: 1 October 2025].