Introduction

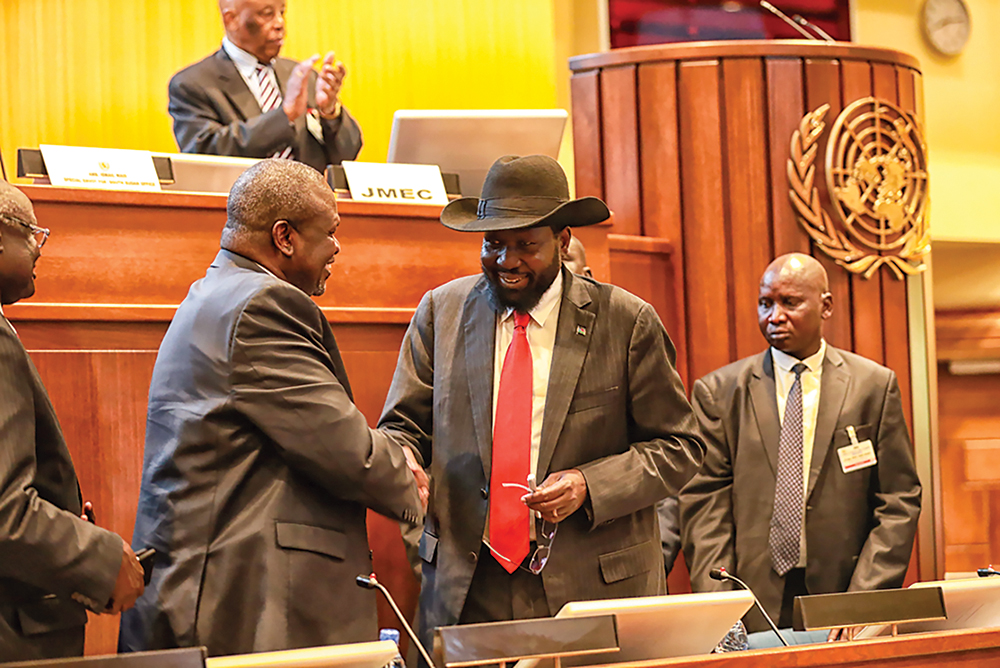

The signing of the Revitalized Agreement on the Resolution of the Conflict in the Republic of South Sudan (R-ARCSS) on 12 September 2018 in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, by the warring parties in South Sudan, has been widely extolled and commended as a significant development signalling the dawn of peace. The peace deal is an attempt to revive the Agreement on the Resolution of the Conflict in the Republic of South Sudan (ARCSS) of 17 August 2015, which had apparently broken down as a result of the outbreak of civil war triggered by the violent confrontations that erupted on the night of 7 July 2016 in Juba. Whilst it is not very surprising that almost all South Sudanese, stakeholders to the conflict and commentators across Africa and beyond have expressed fervent hope, generous optimism and great expectations for peace and stability, given the intractability of the conflict in South Sudan, it is equally important to undertake a timely analysis of the R-ARCSS – specifically the possible and probable interplay of factors that may have implications for the success, or otherwise, of the peace agreement. The idea is always to systematically and constructively identify critical issues that may be pertinent to consider as all relevant stakeholders invest efforts towards peacemaking, peacekeeping and peacebuilding processes in South Sudan. This article therefore examines the R-ARCSS within the context of the South Sudanese internal and external conflict environment, and presents the key enablers and obstacles to the success of the peace agreement.

Background to the R-ARCSS

The R-ARCSS is an agreement that seeks to revive the ARCSS of August 2015, which had temporarily ended the first civil war of South Sudan that broke out on 13 December 2013. Between August 2015 and June 2016, the ARCSS played a noticeable role in constraining the key parties to the conflict from engaging in confrontations, until July 2016 when conflict ensued.

Since the resurgence of civil war in South Sudan on 7 July 2016, there have been efforts to ensure a return to peace in the country through various initiatives at national and regional levels. The establishment of the High Level Revitalization Forum (HLRF) by the Inter-Governmental Authority on Development (IGAD) – a seven-member regional bloc comprising Djibouti, Ethiopia, Kenya, Somalia, South Sudan, Sudan and Uganda – at its Extra-Ordinary Summit of Heads of State and Government on South Sudan on 12 June 2017,1 was instrumental in convening negotiating parties in South Sudan to revive the ARCSS.

The HLRF, after its launch in December 2017, managed to facilitate several negotiations for 15 months between President Salva Kiir Mayardit’s Sudan People’s Liberation Movement and Army in Government (SPLM/A-IG), Riek Machar Teny Dhurgon’s Sudan People’s Liberation Movement and Army in Opposition (SPLM/A-IO) and other opposition political parties, which ultimately culminated in the R-ARCSS. The R-ARCSS was preceded by five key agreements between the parties and stakeholders to the conflict in South Sudan:

- Agreement on the Cessation of Hostilities, Protection of Civilians and Humanitarian Access, signed on 21 December 2017 in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia;

- Addendum to the Agreement on the Cessation of Hostilities, Protection of Civilians and Humanitarian Access, signed on 22 May 2018 in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia;

- Khartoum Declaration of Agreement between Parties to the Conflict in South Sudan, signed on 27 June 2018 in Khartoum, Sudan;

- Agreement on Outstanding Issues of Security Agreements, signed on 6 July 2018 in Khartoum, Sudan; and

- Agreement on Outstanding Issues on Governance, signed on 5 August 2018 in Khartoum, Sudan.

Overview of the R-ARCSS

The principal parties and signatories to the R-ARCSS are Kiir, as president of the Transitional Government of National Unity (TGoNU); Machar of the SPLM-IO; Deng Alor Kuol of the SPLM-Former Detainees (SPLM-FDs); and Gabriel Changson Chang of the South Sudanese Opposition Alliance (SSOA). The other six South Sudan signatories to the peace agreement were Peter Mayen Majongdit, representing the Umbrella Coalition of Political Parties; Kornelio Kon Ngu, representing the National Alliance of Political Parties; Ustaz Joseph Ukel Abango, representing the United Sudan African Party (USAF); Martin Toko Moyi, representing the United Democratic Salvation Front; Stewart Sorobo Budia, representing the United Democratic Party; and Wilson Lionding Sabit, representing the African National Congress (ANC). In addition to this, 16 stakeholders in the form of civil society organisation representatives also appended their signatures to the agreement.

In terms of scope, the R-ARCSS covers issues relating to the Pre-Transitional and Revitalized Transitional Government of National Unity (RTGoNU) governance structures and institutions; permanent ceasefire and transitional security arrangements, humanitarian assistance and reconstruction arrangements; agreed frameworks for resource, economic and financial management; agreed principles and structures for transitional justice, accountability, reconciliation and healing; parameters for guiding the permanent constitution-making process; reconstitution of the Joint Monitoring and Evaluation Commission (JMEC); and operational and amendment procedures for the agreement.

The agreement provides for the establishment of a RTGoNU in South Sudan. This RTGoNU will be mandated to rule for a 36-month transitional period that will commence eight months after the signing of the R-ARCSS. Democratic elections will then be conducted 60 days before the lapse of the transitional period. The same agreement further provides for a single executive president (Kiir), first vice president (Machar) and four vice presidents, nominated by the incumbent TGoNU, SSOA, incumbent TGoNU and former detainees respectively. Whilst the first vice president is mandated to oversee the Cabinet Cluster on Governance Issues, the other four vice presidents will oversee their allocated Cabinet Clusters: the Economic Cluster, Service Delivery Cluster, Infrastructure Cluster, and Gender and Youth Cluster.

The Cabinet of the RTGoNU, as prescribed by the agreement, will have 35 ministers – 20 from the incumbent TGoNU, nine from SPLM/A-IO, three from SSOA, two former detainees and one from other political parties – and 10 deputy ministers (five from the incumbent TGoNU, three from SPLM/A-IO, one from SSOA and one from other political parties). The reconstituted Parliament is very bloated, with 550 members of parliament – 332 from the incumbent TGoNU, 128 from SPLM/A-IO, 50 from SSOA, 30 from other political parties and 10 former detainees.

Possible Obstacles to the Implementation of the R-ARCSS

One of the most frustrating phenomena in South Sudan’s conflict history has been the unwillingness of parties to peace agreements to implement what they agreed upon in good faith. More often than not, agreements are implemented partially, selectively and lackadaisically, for obvious political reasons. This a potential obstacle. A recent example is the announcement of Republic Order Number 17 on 27 September 2018 by Kiir. This decree ordered the chief of the South Sudan Defence Forces, General Gabriel Jok Riak Makol, to release prisoners of war and detainees, cease training of recruits and stop revenge or retaliatory attacks by SPLA forces, as provided for under Chapter 2 of the R-ARCSS relating to Permanent Ceasefire and Transitional Security Arrangements.2 Since the announcement, over 20 political detainees have reportedly been released by the government, despite delays, including James Gadet Dak and William Endley3 – although some political activists (such as Peter Biar Ajak) are yet to be released.4

Another potential hurdle is the apparent lack of urgency, determination, political will and political commitment in implementing even the easier objectives of the peace deal. Granted, it is just over two months after the signing of the agreement, but considering that the pretransitional period lapses on 12 May 2019 to pave the way for the RTGoNU, many outstanding activities could have been completed by this time in pursuit of the set targets outlined in the R-ARCSS Implementation Matrix 2018.5 These outstanding issues include the ratification of the R-ARCSS by the Transitional National Legislature (TNL); the release of prisoners of war and political detainees; the formation of the Joint Defence Board (JDB); the reconstitution of the Joint Military Ceasefire Commission (JMCC); the disengagement and separation of forces by the parties to the agreement; the establishment of the Joint Transitional Security Committee (JSTC) by the parties to the agreement; the drafting of the Constitutional Amendment by the National Constitutional Amendment Committee (NCAC) to incorporate the R-ARCSS into the Transitional Constitution of the Republic of South Sudan (TCRSS); the establishment of a fund for the implementation of pretransitional period activities; the reconstitution of both the Strategic Defence and Security Review (SDSR) Board and the Disarmament, Demobilisation and Reintegration (DDR) Commission by the National Pre-Transitional Committee (NPTC); the creation of an implementation roadmap and budget for pretransitional period political tasks; and IGAD tasks that include the appointment of the reconstituted JMEC chairperson, the approval of the Reconstituted Joint Monitoring and Evaluation Commission (RJMEC) terms of reference, the reconstitution of the NCAC, and the establishment of the Independent Boundaries Commission and the Technical Boundaries Commission.6 At this pace, one may raise the legitimate fear that the provided 36-month transitional period, to be presided over by the TGoNU, may be too short to effectuate genuine institutional reforms that will stabilise the country and usher democratic elections.

Of course, it has to be acknowledged that progress has been recorded in some instances. For example, the SPLM/A-IO, FDs party and the SSOA managed to ratify the R-ARCSS on 22, 25 and 28 September 2018 respectively, consistent with the provisions of Article 8.1 of the agreement.7 In addition, a number of confidence-building measures have been undertaken, as provided for in the R-ARCSS – including the meeting of R-ARCSS signatories and stakeholders in Sudan on 22 September 2018 to celebrate the signing of the agreement; the declaration of commitment to support the R-ARCSS by the TGoNU, SPLM/A-IO and SSOA; the convening of a workshop on Permanent Ceasefire and Transitional Security Arrangements on 24–25 September 2018; the appointment of the NPTC on 25 September 2018; the reconstitution of the Ceasefire and Transitional Security Arrangements Monitoring Mechanism Board on 27 September 2018; and the meeting of the Ceasefire and Transitional Security Arrangements and Verification Mechanism Technical Committee in Sudan on 9–11 October 2018.8

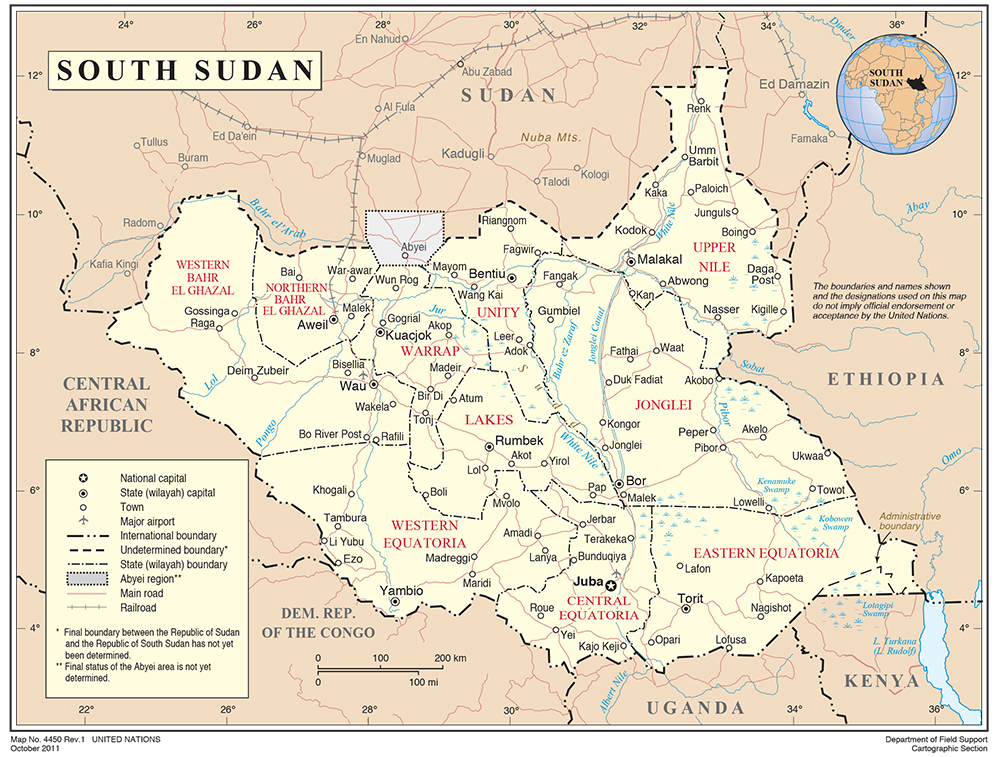

However, another possible obstacle to the implementation of the R-ARCSS may be the deep-seated mistrust and suspicion between and among the parties to the agreement, which cannot be masked. Such antagonism can be understood, given the prolonged rivalry that has manifested in experiences of horrendous and unpalatable intercommunal clashes between their respective followers across South Sudan. Since the outbreak of the second civil war in December 2016, Kiir has, on several occasions, declared his unwillingness and unreadiness to work with Machar, citing the latter’s intransigence.9 In this context, the parties to the R-ARCSS will inevitably suspect each other’s intentions, motives and behaviours, especially when it comes to the design, constitution and operationalisation of historically controversial and politically sensitive provisions relating to the number and boundaries of states in South Sudan (Article 1.15), permanent ceasefire and transitional security arrangements (Article 2.4), transitional justice, reconciliation and national healing (Article 5.1), among others. This distrust may ultimately undermine the willingness of the RTGoNU parties to constructively engage, share information and cooperate. This usually minimises the potential of most transitional authorities and peace pacts.

Related to the previous challenge is the agreement’s failure to address some of the root causes of the conflict in South Sudan. Some of the most serious root causes of the conflict, as also noted in the Final Report of the African Union Commission of Inquiry on South Sudan of 2014, includes the lack of solid democratic institutions and the continued conflation of personal, ethnic and national interests, together with the inequitable distribution of resources in South Sudan.10 Chapter 1 provisions on Transitional Institutions and Mechanisms, and Chapter 4 provisions on Resource, Economic and Financial Management – which collectively seek to address some of the root causes of the conflict – have for long been enshrined in previous peace agreements, but have not delivered any change. The R-ARCSS mediators needed to understand why this has been the case, and devise more innovative and creative interventions.

The abuse and manipulation of state institutions, as well as the perpetuation of patronage networks across all institutions and regions for political capital, especially security sector organs, remains one of the conflict drivers. Regardless of this phenomenon, Article 1.6 on the Powers, Functions and Responsibilities of the President gives carte blanche to the incumbent president, despite the relatively negligible and politically inconsequential accountability checks attempted through Article 1.9 provisions relating to “collegial collaboration in decision-making and continuous consultation”. The South Sudanese body politic may remain vulnerable and unshielded from the political risks and hazards of strongman politics, given the continued existence of an immensely powerful president. Although IGAD should be credited for allowing a revitalised JMEC to continue to monitor and evaluate the ARCSS, as well as to report implementation progress (and non-implementation) to both the RTGoNU and the IGAD chairperson, the reality is that the body remains burdened with huge responsibilities, without much commensurate power. Its effectiveness is therefore dependent upon the goodwill and cooperation of the conflicting parties.

The expanded nature of the RTGoNU provided for in the R-ARCSS may present a stumbling block in pursuit of the agreement’s objectives. One may easily understand that the expanded Presidium, Cabinet and Parliament were deliberately designed to pragmatically fit the Procrustean bed of South Sudanese political reality. However, the required budgetary resources to support and sustain a government of five vice presidents; 45 ministers (inclusive of deputy ministers); 550 members of parliament; and several transitional commissions, boards and committees will certainly be burdensome to a country already weighed with arrears in excess of 17 billion South Sudanese pounds (an excess of USD130 million), comprising “three months of national salaries, five months of state transfers and twelve months of embassies’ salaries”, including members of the Transitional National Legislative Assembly.11 With the previous peace agreement (ARCSS) having already used 1.6 billion South Sudanese pounds during the first three quarters of the 2017/18 fiscal year,12 an additional financial burden would be strenuous and taxing against the backdrop of a debilitated economy. This weakens the peace agreement implementation capacities and capabilities of the government. As admitted in the National Budget Speech of South Sudan for 2018/2019:

The productive sectors like agriculture, livestock and fisheries have stagnated; local and international investments have stalled. Consequently, the economy has been experiencing serious hyperinflation reaching triple digits (113%) since February 2018 […] Unemployment has also reached unprecedented levels and so is poverty […] Our oil and non-oil revenue performance has exceeded the budget estimates but the increase has not been sufficient enough to bridge our funding gap. Furthermore, we have been unable to raise new financing.13

With the competing national budget demands for social service delivery and development, the RTGoNU has to exercise economic discipline through tenacious frugality and thriftiness in resource use and expenditure to ensure that the R-ARCSS implementation activities are sufficiently funded. A delicate balance was needed to pursue accommodative objectives in the R-ARCSS whilst considering the fiscal realities.

The implementation of transitional justice, reconciliation and national healing provisions of the R-ARCSS may emerge to be problematic. Whilst the establishment of the Commission for Truth, Reconciliation and Healing (CTRH), Hybrid Court for South Sudan (HCSS) and the Compensation and Reparation Authority (CRA) are sound initiatives meant to collectively promote and facilitate truth-telling, restorative and rehabilitative justice, reconciliation and national healing, compensation and reparation of victims of violence, and investigation and prosecution of those alleged to have committed crimes against humanity in South Sudan, the leaders are most likely to be reluctant to implement these, given the prospects of their liability and culpability. The Final Report of the African Union Commission of Inquiry on South Sudan of 2014, which the R-ARCSS recommends as useful material for the investigation and prosecution of those alleged to have committed human rights violations and crimes against humanity, states that there was overwhelming evidence gathered through testimonies and field visits to the effect that the SPLM/A-IG, SPLM/A-IO and other opposition armed groups engaged in tragic human rights violations and abuses through abductions; illegal detentions; rape; sexual violence; systematic torture; cruel, inhumane and degrading treatment of civilians; looting; property destruction; and indiscriminate killings using cluster bombs in various sites, cities, towns and villages in South Sudan.14 What may be disturbing is the fact that the 2015 ARCSS had provided for the establishment of the HCSS by the African Union (AU) Commission, but it remains unimplemented – except the development (in 2017) of a draft statute of the court and a memorandum of understanding between the AU and South Sudan on the establishment of the court, which were both unapproved by the country’s Council of Ministers, as it emerged that a “number of key Ministers opposed the court”.15

Key Enablers to the Success of the R-ARCSS

Notwithstanding the possible obstacles that may frustrate the implementation of the R-ARCSS, there are a considerable number of factors which will ensure that the agreement delivers its overarching objective of laying a foundation for a united, peaceful and prosperous South Sudan.

In terms of content and substance, the R-ARCSS represents a solid pact as it contains the requisite procedural, substantive and institutional components expected of any sustainable peace agreement. This is an enabler. What will then be needed is political will and commitment to implement the letter and spirit of the agreement.

The fact that the peace pact is politically inclusive and representative – unlike its predecessor, the ARCSS – is a necessary condition for successful implementation. Whilst there are still arguments that a few influential individuals and armed groups – such as splinter factions of some parties like the SSOA – are opposed to the agreement,16 the extent of inclusivity of the agreement should be commended as a basis for continuous engagement with non-signatory parties.

The legitimacy of the R-ARCSS is another enabler. Generally, there is substantial local ownership of the agreement, and regionally and internationally, there seems to be consensus that the peace pact is acceptable. Whilst the international community appears sceptical – understandably so, given the historical trend of peace agreement violations in South Sudan – they have pledged to support the peace process. The Troika of the United Kingdom, United States of America and Norway expressed its “concern about the parties’ level of commitment to [the] agreement”,17 but acknowledged that the agreement is key in addressing peace and security in South Sudan, whilst the United Nations spokesman for the Secretary-General on South Sudan welcomed the peace pact as “a positive and significant development”.18 Legitimacy will be an enabler of success, as it often assists to mobilise the necessary support for the durability and sustainability of peace agreements.

The implementation of the R-ARCSS provisions relating to the establishment of the CTRH, HCSS and the CRA will promote justice, unity, reconciliation and address impunity. This will enable the achievement of the agreement’s goals and objectives, given the importance of justice, reconciliation and national healing in any peacebuilding process.

The effectiveness of IGAD will also determine the success of the R-ARCSS. It is necessary to recognise and anticipate that there are parties and individuals that are ready to undermine the R-ARCSS through covert and overt means in defence of their constituent interests, power and ideologies. The ability of IGAD to intervene effectively to manage peace spoilers or resisters will be critical in facilitating the smooth implementation of the peace pact.

Overall, building trust, cooperation and interparty collaboration in implementing the R-ARCSS will be the greatest facilitator of success. Whilst it is conventional wisdom that in protracted and intractable conflicts, distrustful parties often sign peace agreements under political pressure to end human suffering, the peace implementation process often presents an opportunity to reinforce and fortify not only overlooked or imperfect provisions in the peace pact, but also to detoxify political relations, transform political attitudes and re-establish unity of purpose. Thus, the commitment of R-ARCSS parties to invest in attitudes, institutions and structures that strengthen positive peace and build conflict resilience in South Sudan will be key. The leadership, in collaboration with all stakeholders, must work towards sustaining the central pillars of positive peace – that is, a well-functioning government, democracy and rule of law, an environment conducive for business, equitable distribution of resources, and human capital development. Most importantly, the ability to institute and capacitate peacebuilding structures and systems that will proactively prevent and peacefully manage and resolve future conflicts will be fundamental in the implementation of the R-ARCSS. Such tasks should never be assumed to be facile and simplistic, considering the history of South Sudan’s conflicts and its current ranking as the most fragile state in the world.19

Conclusion and Way Forward

The R-ARCSS has the potential to facilitate a return to peace, stability, reconciliation, unity and prosperity in South Sudan. Potential obstacles lie ahead in the form of lack of political will and determination, interparty distrust and suspicions, failure to address some of the root causes of the conflict, resource constraints, and the inevitable resistance by some parties to implement politically sensitive provisions of the R-ARCSS. Enablers that facilitate the successful implementation of the peace pact exist: a solid agreement in terms of content and substance, the inclusive and representative nature of the agreement, legitimacy, the role of IGAD, the ability to cultivate and sustain interparty trust and cooperation, and the effective implementation of provisions relating to justice, national healing and reconciliation. Faced with this reality, the R-ARCSS should present another opportunity for all parties to renew constructive working relations and unite their constituents at a time when the country is characterised by deeply rooted social divisions. This would require extensive and committed long-term efforts towards progressive trust and confidence-building measures as a foundation of engagement. For this to succeed, all citizens and stakeholders have to play their part.

Endnotes

- Inter-Governmental Authority on Development (IGAD) (2017) ‘Communiqué of the 31st Extra-Ordinary Summit of IGAD Assembly of Heads of State and Government on South Sudan’.

12 June, Addis Ababa, p. 4, Available at: <https://igad.int/attachments/article/1575/120617_Communique%20of%20the%2031st%20Extra-Ordinary%20IGAD%20Summit%20on%20South%20Sudan.pdf> [Accessed 20 September 2018]. - Radio Tamazuj (2018) ‘South Sudan Government Releases 20 Political Detainees’, 3 October, Available at: <https://radiotamazuj.org/en/news/article/south-sudan-government-releases-20-political-detainees> [Accessed 5 October 2018].

- Sudan Tribune (2018a) ‘South Sudanese Authorities Release SPLM-IO’s James Dak’, 2 November, Available at: <http://www.sudantribune.com/spip.php?article66539> [Accessed 2 December 2018].

- Amnesty International (2018) ‘South Sudan: Release Academic and Activist Peter Bjar Ajak’, 16 October, Available at: <https://www.amnesty.ie/south-sudan-release-academic-and-activist-peter-bjar-ajak/> [Accessed 2 December 2018].

- IGAD (2018) ‘Revitalized Agreement on the Resolution of the Conflict in the Republic of South Sudan (R-ARCSS)’,

12 September, Addis Ababa, pp. 86–121, Available at: <https://igad.int/programs/115-south-sudan-office/1950-signed-revitalized-agreement-on-the-resolution-of-the-conflict-in-south-sudan> [Accessed 15 September 2018]. - Ibid., pp. 2–3.

- Joint Monitoring and Evaluation Commission of South Sudan (JMEC) (2018) ‘Progress Report No. 2: Status of Implementation of the R-ARCSS 2018, October 12, 2018’, p. 2, Available at: <https://jmecsouthsudan.org/index.php/reports/r-arcss-evaluation-reports/115-interim-status-update-d-day-30-days-of-the-implementation-of-the-revitalised-agreement-on-the-resolution-of-the-conflict-in-south-sudan-r-arcss-october-12-2018/file> [Accessed 14 October 2018].

- Ibid., p. 2.

- Sudan Tribune (2018b) ‘S. Sudan’s Kiir Not Ready to Work with Machar: Official’, 21 June, Available at: <http://www.sudantribune.com/spip.php?article65701> [Accessed 20 October 2018].

- African Union (2014) Final Report of the African Union Commission of Inquiry on South Sudan, 15 October, p. 20.

- Republic of South Sudan Transitional Government of National Unity (2018) ‘Budget Speech FY 2018/19’, p. 3, Available at: <http://grss-mof.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/Budget-Speech-Final-July-12-_-12-05-pm.pdf> [Accessed 4 October 2018].

- Ibid., p. 2.

- Ibid., p. 2–3.

- African Union (2014) op. cit., pp. 215–229.

- Human Rights Watch (2017) ‘South Sudan: Stop Delays on Hybrid Court’, 14 December, Available at: <https://www.hrw.org/news/2017/12/14/south-sudan-stop-delays-hybrid-court>

[Accessed 18 October 2018]. - Sudan Tribune (2018c) ‘SSOA Parties Defend South Sudan Peace Pact, Call on “Splinters” to Rejoin Them’, 17 September, Available at: <http://www.sudantribune.com/spip.php?article66260>

- US Embassy in South Sudan (2018) ‘Troika Statement on the South Sudan Peace Talks’, 12 September, Available at: <https://ss.usembassy.gov/troika-statement-on-the-south-sudan-peace-talks/> [Accessed 20 October 2018].

- United Nations (2018) ‘Statement Attributable to the Spokesman for the Secretary-General on South Sudan’, 13 September,

Available at: <https://www.un.org/sg/en/content/sg/statement/2018-09-13/statement-attributable-spokesman-secretary-general-south-sudan> [Accessed 20 October 2018]. - Fund for Peace (2018) ‘2018 Fragile States Index’, pp. 6–7, Available at: <https://fundforpeace.org/fsi/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/951181805-Fragile-States-Index-Annual-Report-2018.pdf> [Accessed 23 October 2018].