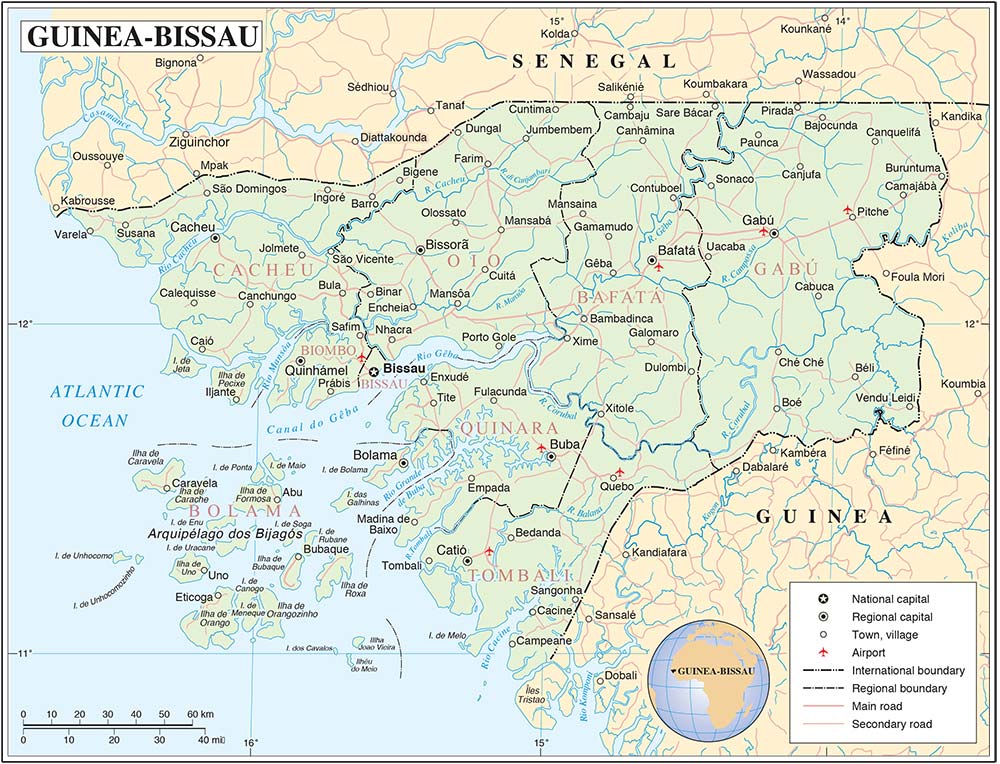

Women’s organisations aimed at conflict resolution have been active in Guinea-Bissau in the past decade under the auspices of international and regional bodies, particularly the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) and the United Nations (UN). Guinea-Bissau is a small West African country of about 1.8 million inhabitants1 that declared independence from Portugal in 1973 after a long independence war. The country’s recent history has been marked by repeated military coups, political assassinations and fragile state institutions. This article examines the role of women’s organisations in peacebuilding and conflict resolution in a country marked by prolonged and systemic political crises.

Women’s Mediating Networks in Africa

Both the Sustainable Development Goals (2030 Agenda) – particularly Goals 5, 10 and 16 – and the African Union’s (AU) 2063 Agenda share a strong focus on gender equality and women’s empowerment. Gender inequality is addressed in both agendas by recognising its structural causes, including the unequal distribution of power, resources and opportunities, and how they stimulate gender violence, insecurity and lack of access to justice and affect inclusivity. However, the gender dimensions of conflict and women’s roles in peacekeeping remain marginal in conflict resolution and post-conflict reconstruction processes.2

The low level of participation of African women in peace processes (particularly as mediators in conflicts) was recognised and addressed in the 1994 Kampala Action Plan on Women and Peace, and reaffirmed in several international agreements since then. Commitments made to increase women’s participation in mediation and peace processes highlighted that women are not solely victims of war but also play important roles in peacebuilding. The participation of African women in formal mediation processes and peace discussions, in particular, is an important focus of UN Security Council (UNSC) resolutions 1325 (2000) and 1960 (2010), which remain poorly implemented, albeit after almost two decades of efforts. Resolution 1325, a ground-breaking decision on women, peace and security, sets the international legal framework that emphasises the importance of equal and full participation of women as active agents in peace and security. It further recognises women’s undervalued and underutilised contributions to conflict prevention, peacekeeping, conflict resolution and peacebuilding; the disproportionate and unique impact of armed conflict on women; and the central role that women play in conflict management, conflict resolution, security and sustainable peace. To increase women’s access to, and participation in, peace mediation and negotiations, women’s capacity for mediation and negotiation needs to be enhanced and extended in all areas, including security sector reform, finance and power-sharing. The impact of conflict on women and their role in peace processes needs to be better exposed and reflected on. The implementation of various policies related to women, peace and security (WPS) needs to be accelerated and monitored. The implementation of several networks of women mediators at the continental, regional and national level in Africa is part of the peacebuilding efforts in response to the previously mentioned UN resolutions and their follow-up within the African Peace and Security Architecture (APSA) implemented by the AU. In this context, the AU encouraged the creation of FemWise-Africa (Network of African Women in Conflict Prevention and Mediation), established in 2017. FemWise-Africa aims to strengthen the role of women in conflict prevention and mediation efforts in the APSA. The network provides a platform for strategic advocacy, capacity-building and networking to improve the implementation of commitments to include women in peacebuilding in Africa. It is also intended to be a platform that brings together different women, from political leaders to representatives of civil society organisations (CSOs), religious leaders, business and entrepreneurial members, and local and community mediators, to work in the different areas of mediation.3

Within the African continent, FemWise-Africa sets the agenda for local and national women mediator networks, bringing together women acting at the local level with national, higher-level mediators and bridging their differences. Networks of women mediators have been effective at different levels:

- creating repositories of women experts, with experience in peace processes and conflict management;

- ensuring training for women involved in mediation and peacebuilding;

- creating platforms for experience-sharing between women working in different tracks of conflict resolution;

- empowering local women and giving visibility to the work of mediators and their impact on peace processes; and

- highlighting the role of local women in peacebuilding.4

The number of women mediator networks is growing worldwide and a Global Alliance of Regional Women Mediator Networks was recently created,5 reuniting FemWise-Africa, the Arab Women Mediators Network – League of Arab States, the Mediterranean Women Mediators Network, the Nordic Women Mediators and the Women Mediators Across the Commonwealth.6

Women mediator networks follow the multitrack approach, recognising the role of different actors and diverse approaches to conflict mediation. Track One implies high-level political talks involving the conflict parties, Track Two involves influential individuals from business, religious organisations or CSOs, and Track Three reunites grassroot activities.7 The majority of women’s organisations are active in conflict resolution work at the community level and are defined as Track Three mediators. However, the main networks present at the continental and global levels have a strong emphasis on Track One and Track Two mediation.

Peacebuilding in Guinea-Bissau: An Overview

Guinea-Bissau is characterised by continued political instability marked by successive conflicts and wars. The country obtained its independence after a long nationalist war (1963–1974) against the Portuguese colonial administration. The main nationalist movement leading the independence war, the African Party for the Independence of Guinea and Cape Verde (PAIGC), became the ruling party and has been in power, almost uninterrupted, since 1974. The newly independent country was first dominated by an army, with the legitimacy of having been the freedom fighters. The first president, Luís Cabral, a civilian, was overthrown by the army leader and prime minister, Nino Vieira, in a military coup in 1980. Vieira was a despotic leader who managed to stay in power for 18 years by murdering his main opponents and winning the first multilateral presidential elections in 1994. In 1998, a conflict between Vieira and his army chief, Ansumane Mané, led to a civil war that devastated the capital Bissau, while part of its population fled. Since 1999, the country’s politics have been marked by sudden or violent changes in government, in 2003, 2009 and with the military coup of 2012. In 2019, political tensions between the president and the main party, the PAIGC, also led to an ungovernable situation, which required the intervention of the international community at several points.

Despite this context of continuous political turmoil, disputes in the last two decades (that is, after the 1998–1999 civil war) never advanced to widespread conflict at the national level. These struggles have been felt mainly at the political and military levels, and have been located mostly in the capital city. However, this climate of political turbulence has justified the constant presence of international organisations leading peacebuilding initiatives in the country, and has defined the agendas of key members of the international community acting in Guinea-Bissau. It should be noted that although the country is considered to be in moderate conflict, it is part of the Senegambia conflict system, which also includes The Gambia and the Casamance region in Senegal. Tensions in each of these regions or countries spills over to the neighbouring territories, mostly between the Casamance region and Guinea-Bissau. From the perspective of international actors – principally ECOWAS – peacekeeping, peacebuilding and security solutions must be sought throughout the region.8 Peacebuilding initiatives in Guinea-Bissau are a priority for the international community, supporting reform of the security sector, a review of the national legal system and integration of restorative justice, and grassroots networks for peace.

Following the 1998/1999 conflict, the UNSC, according to its resolution 1233 of April 1999, established the UN Peacebuilding Office for Guinea-Bissau (UNOGBIS), led by a special representative of the UN Secretary-General, with the mission of facilitating general elections. The mission was extended several times, and in 2009 the delegation became the UN Integrated Peacebuilding Office in Guinea Bissau (UNIOGBIS), with a mandate term deadline in late 2020. Its main objective is peacebuilding in Guinea-Bissau, having worked in conjunction with the UN Peacebuilding Commission (UNPBC) and the UN Peacebuilding Fund (PBF).

The ECOWAS presence in Guinea-Bissau has been an essential peace-maintaining guarantee since the 1998–1999 conflict. In 1998, ECOWAS was crucial for the establishment of the Abuja Agreement and the creation of the Interposition Force of the Military Observer Group of the Economic Community of West African States (ECOMOG).9 After the 12 April 2012 coup d’état, ECOWAS led efforts to produce a roadmap for peace, structuring an agreement signed in Bissau by the parties. It also created the ECOWAS Mission in Guinea-Bissau (ECOMIB) to provide security and, following the restoration of constitutional order, assisting the new government to consolidate its authority and address security challenges.10 At a local level, ECOWAS has maintained the activities of the West Africa Network for Peacebuilding (WANEP). Founded in 1998, WANEP has implemented a regional early warning and response system (ECOWARN) since 2002. Guinea-Bissau has established a National Early Warning System (NEWS), with community monitors across the country. This early warning system, which is also linked to the ECOWAS Response and Early Warning Mechanism – ECOWARN – ensures the collection and analysis of early warning conflict data to alert policymakers to the implications of the measures taken or not taken.

In 2013, the main international actors, responding to the UN Secretary General’s call, created a coordination and understanding platform, P5, which includes ECOWAS, UNIOGBIS, the Community of Portuguese Speaking Countries (CPLP), the European Union (EU) and the AU. In 2014, a successful double-election process led to the constitution of an internationally recognised new government and president. The new government started a negotiation process with the EU and guaranteed substantial financial support for structural reform of the economic sector in Guinea-Bissau, which was never implemented due to another political crisis in 2015 – this time between the elected president, the prime minister and president of the main party, the PAIGC.11 Again ECOWAS intervened, acting as a broker between the parties and ensuring an agreement that established the main points for a compromise government until the next electoral cycle in 2018, which was later postponed to 2019. This agreement was signed by the representatives of the main political forces, the National Assembly, and religious and civil society organisations (CSOs), and consists of two documents: the Six-point Roadmap and the Conakry Agreement.12 Elections were set for 10 March 2019, but the PAIGC, the most voted party, did not win an absolute majority in Parliament. Successive proposals for constituting a government were dismissed, maintaining the threat of a political crisis. This was finally overcome in July 2019 when, after another ECOWAS intervention, a new government proposed by the PAIGC was recognised by the president and the National Assembly. The ECOWAS intervention also recognised that presidential elections were due in late 2019, and that the president, José Mário Vaz, is limited to representative functions since 23 June 2019, the term of his constitutional mandate.

Women’s Representation in Peace Processes in Guinea-Bissau

In Guinea-Bissau, women’s participation in political processes has been levered by international organisations, mainly UNIOGBIS and ECOWAS. Their joint efforts supporting women CSOs working in peacebuilding and civil interventions led to the visible strengthening of women’s political participation. Women’s organisations are now nationally recognised as actors in peacebuilding processes. This section provides an overview of the main national women’s organisations and their work in peacebuilding and fighting inequalities.

Gender inequality is rooted in structural violence that relegates women to marginality and economic dependence, while having more family responsibilities and enduring domestic subordination. It is seen in different kinds of formal education (where the girls’ dropout rate is higher than for boys), economic status and access to paid jobs, and women’s underrepresentation in high-level institutions such as parliament and government. Guinea-Bissau has signed and ratified every international agreement to end gender discrimination and adopted legislation accordingly – such as the law to combat female genital mutilation (2011) or the criminalisation of gender-based violence. However, at a political level, women are still underrepresented. As in other parts of the continent, gender inequality and women’s political representation was first addressed by the main nationalist movement – in this case, the PAIGC, which has included a few women in government since independence. Still, this participation was never representative or expressive of a real change of women’s status in the country. Women’s representation decreased after the implementation of a system based on multiparty elections, a trend common in other countries that was only overcome with the adoption of quota laws.13 The number of women members of parliament decreased from 20% in 1988 (under the single-party regime) to a constant 10% or 11% in recent years, rising to 13% in the last elections.14 A shift in women’s political representation in the government took place following the March 2019 elections, with 11 women being represented: eight as ministers and three as state secretaries. The visibility of women’s organisations in peacebuilding in recent years, supported by ECOWAS and UNIOGBIS, has strongly contributed to this improvement in women’s representation.

ECOWAS launched a specific programme on women in peacebuilding (WIPNET) in 2001, aimed at promoting a gender perspective in peacebuilding and conflict prevention activities that has representatives at community, regional and national level in Guinea-Bissau. ECOWAS also supports the network of women for peace and security (REMPSECAO) as part of the Programme for the Promotion and Development of Peace, Security and Good Governance. This network aims to coordinate and optimise women’s initiatives in conflict prevention and resolution, peacekeeping and post-conflict reconstruction operations. REMPSECAO has been active in Guinea-Bissau since 2009, with the additional support of UNIOGBIS since 2013. It promotes dialogue between political actors and has been leading extensive work on peacebuilding awareness within the army.

UNIOGBIS is mandated to include women in conflict resolution and peace processes. It follows the requirements of UNSC resolution 1325 of 2000 and the National Action Plan for the Implementation of Resolution 1325 of 2010, which affirm the need for effective representation of women in all sovereign bodies. Aiming at boosting women’s participation in peacebuilding processes and in political representation, UNIOGBIS supported the creation of several women’s organisations. The most active of these are the Women’s Political Platform (PPM), created in 2008; the Women Mediator Network (REMUME), created in 2016; and the Group of Women Facilitators, created in 2017 and recently reorganised as the Guinean Council of Women Facilitators for Dialogue (CMGFD). UNIOGBIS’s role was crucial for the implementation of the roadmap for gender-inclusive policy, known as the Canchungo Declaration of October 2014.15 Within the joint agendas of ECOWAS and UNIOGBIS, different women’s organisations working for peace and conflict resolution in Guinea-Bissau are active at Track Two and Track Three levels.

PPM is the oldest of these women’s organisations and encompasses eight CSOs and every political party. Women commonly expressed that political parties use them to mobilise votes but do not take them seriously as political candidates. It was felt that apart from the sensitisation of political parties’ leadership, activities should be undertaken to boost women’s capacity, as well as their motivation to engage effectively in formal politics alongside their male counterparts. PPM operates at different levels and has been instrumental in the creation of laws combating gender inequality and gender violence and criminalising female genital mutilation (2011). With the support of the Network of Women Parliamentarians, PPM was also key in establishing a gender quota law in 2018.16 It has a well-established women’s network in the provinces that facilitates the creation of other networks, such as, REMUME.

At the Track Two level, the most visible organisation is the CMGFD. Created in 2018 by the Women’s Civil Society Forum, the CMGFD initially brought together 10 women with different backgrounds occupying positions of public visibility and leadership. The group led several initiatives, ranging from dialogue promotion to peaceful and well-mediated processes, and is involved in observation and pressuring rather than mediation in the sense of proposing formulas for an end to impasse.17 he leader is a well-known businesswoman who has been facilitating peace dialogues since the conflict of 1998.

REMUME was created in 2016 to support, strengthen and improve the skills of a critical mass of women and young mediators, and to encourage their participation, active role and effective involvement in peace processes and peacebuilding efforts in the country. REMUME has mostly been effective as community mediation. At a local level, REMUME is a platform that unites both men and women working with different organisations in conflict management. The main conflicts mediated are related to land disputes, inheritance, gender violence and cattle theft. Mediators are trained by different CSOs. REMUME includes mediators participating in organisations such as Voz di Paz, a CSO created in 2007 with UN support and the mandate to help create and broaden dialogue on the main obstacles that hinder peace in the country and to support local, national and regional actors to prevent future conflict. Voz di Paz also developed a useful participatory conflict analysis through a country-wide consultation process (peace mapping). Other organisations working in community conflict mediation include Kumpudur di Paz; the Network Against Gender Violence (RENLUV), created in 2003 and active in the areas of prevention, reduction and combating of gender- and child-based violence; the National Committee for the Abandonment of Harmful Traditional Practices for Women and Child Health (CNAPN); the Friends of Children Association (AMIC); and local representatives of WANEP. The creation of REMUME was crucial for the affirmation of women in local conflict management and mediation – a role usually attributed to the male-dominated group of traditional and religious authorities and, in recent years, to the Justice Access Centres. It reunites women with national political profile and local activists, and is by far the network with the strongest potential for implementing FemWise’s objectives for women’s mediation.

Conclusion

Women’s representation in mediation processes has been improving worldwide, and particularly on the African continent. Conflict and post-conflict situations are increasingly being addressed by women participating at the different axes of conflict management, with a strong emphasis on community interventions (Track Three). Guinea-Bissau, a country long characterised by protracted political instability, has experienced long-term interventions from the international community supporting peacebuilding efforts, particularly by the UN, ECOWAS, AU, EU and CPLP. At a higher political level, the continuous support of ECOWAS in peace mediations has been effective in realising elections and monitoring the implementation of signed agreements between different parties. ECOWAS’s role was essential in overcoming the crisis between the elected president and the leaders of the PAIGC, the main voted party.

To contain tensions and overcome conflicts, international organisations have been supporting women facilitators and mediator organisations. These women’s organisations are mostly active at the communal level, being present in almost every village. Their roles are becoming more visible at a national level, due to their high level of participation and successful mediated activities. The joint efforts of these networks and their supporters, mostly ECOWAS and UNIOGBIS, are successful in empowering women and highlighting the need for equitable gender representation in peacebuilding efforts. The new elected government reacted to these efforts by including eight women in main ministries. Women’s participation in peacebuilding activities and mediation processes at all levels are already proving very effective in Guinea-Bissau.

Endnotes

- The World Factbook. Central Intelligence Agency. Africa: Guinea Bissau. Available at: <https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/pu.html> [Accessed 26 November 2019]

- Eze, Chukwuemeka B. and Albert, Isaac O. (2017) Resolving the Protracted Political Crises in Guinea-Bissau: The Need for a Peace Infrastructure. Conflict Trends, 2017 (2), Available at: <https://accord.org.za/conflict-trends/resolving-protracted-political-crises-guinea-bissau/> [Accessed 9 August 2019].

- FemWise-Africa (n.d.) ‘Strengthening African Women’s Participation in Conflict Prevention, Mediation Processes and Peace Stabilisation Efforts. Operationalisation of “FemWise-Africa“‘, Available at: <http://www.peaceau.org/uploads/final-concept-note-femwise-sept-15-short-version-clean-4-flyer.pdf> [Accessed 10 August 2019].

- Leonardsson, Hanna and Rudd, Gustav (2015) The “Local Turn” in Peacebuilding: A Literature Review of Effective and Emancipatory Local Peacebuilding. Third World Quarterly, 36 (5), pp. 825–839, Available at: <https://doi.org/10.1080/01436597.2015.1029905> [Accessed 10 August 2019].

- Limo, Irene (2018) What Do Networks of Women Mediators Mean for Mediation Support in Africa? Conflict Trends, 2018 (1), Available at: <https://accord.org.za/conflict-trends/what-do-networks-of-women-mediators-mean-for-mediation-support-in-africa> [Accessed 9 August 2019].

- See: ‘A Global Alliance of Regional Women Mediator Networks’, Available at: <https://globalwomenmediators.org> [Accessed 11 November 2019].

- Herrberg, Antje, Gündüz, Canan and Davis, Laura (2009) ‘Engaging the EU in Mediation and Dialogue. Reflections and Recommendations: Synthesis Report’, IFP Mediation Cluster, Available at: <https://www.ictj.org/publication/engaging-eu-mediation-and-dialogue-reflections-and-recommendations-synthesis-report> [Accessed 9 August 2019].

- Herpolsheimer, Jens (2019) Spatializing Practices of Regional Organizations during Conflict Intervention: The Politics of ECOWAS and the African Union in Guinea-Bissau. Unpublished doctoral thesis, University of Leipzig: Leipzig.

- See: United Nations Peacemaker, Available at: <https://peacemaker.un.org/guatemala-abujaagreement9> [Accessed 11 November 2019].

- See African Union (n.d.) ‘Mission in Guinea-Bissau (ECOMIB) – ECOMIB I & II’, Available at: <https://www.africa-eu-partnership.org/en/projects/mission-guinea-bissau-ecomib-ecomib-i-ii> [Accessed 11 November 2019].

- Both the elected president, José Mário Vaz, and the prime minister, Domingos Simões Pereira, were members of the same party, PAIGC. Pereira doubled as president of the PAIGC. The clash between the two personalities has marked the political landscape of Guinea-Bissau. For detailed information, see: Brown, Odigie (2019) ECOWAS’s Efforts at Resolving Guinea-Bissau’s Protracted Political Crisis, 2015-2019. Conflict Trends, 2019 (2), Available at: <https://accord.org.za/conflict-trends/ecowass-efforts-at-resolving-guinea-bissaus-protracted-political-crisis-2015-2019/> [Accessed 11 November 2019].

- The Conakry Agreement, reached at the conclusion of the 11–14 October 2016 mediation, is part of the implementation of the Six-point Roadmap adopted by ECOWAS, entitled “Agreement on the Resolution of the Political Crisis in Guinea-Bissau” and signed in Bissau on 10 September 2016. For further information, see: Eze, Chukwuemeka B. and Albert, Isaac O. (2017) op. cit.

- For further discussion, see: Kang, Alice (2013) The Effect of Gender Quota Laws on the Election of Women: Lessons from Niger. Women’s Studies International Forum, 41 (2013), pp. 94–102.

- Barros, Miguel and Semedo, Odete (2013) A Participação das Mulheres na Política e na Tomada de Decisões na Guiné-Bissau. Da consciência, percepção à prática política. Bissau: UN.

- United Nations Integrated Peacebuilding Office in Guinea-Bissau (UNIOGBIS) (2015) ‘Declaração de Canchungo’, 18 February, Available at: <https://uniogbis.unmissions.org/en/node/100041325.>

- PPM’s initial proposal was the creation of a “zipping mechanism” – that is, a mandatory alternation of female/male names in the electoral rolls presented by political parties. Finally, a quota law of 36% of women nominations in the rolls was approved, but the relegation of women candidates to the last positions on the lists led to an effective representation of 13% of women in Parliament.

- Abdenur, Adriana Erthal (2018) ‘Gender and Mediation in Guinea-Bissau. The Group of Women Facilitators’, Available at: <https://igarape.org.br/en/innovation-in-conflict-prevention/> [Accessed 11 August 2019].