Introduction

It is now commonplace that every election in any country across Africa is a defining moment for statebuilding or a potential source of conflict – and for countries coming out of civil war, the stakes are even higher. Therefore, systems and structures must be operationalised as a catalyst to prevent or avert political violence in times of elections. In West Africa, National Elections Response Groups (NERGs) are being developed as response structures to mitigate election-related conflict, and their operationalisation is proving to be successful in a number of countries that have held elections – including, most recently, in Sierra Leone. NERGs are designed as infrastructures for peace, and serve as platforms for peaceful dialogue and shuttle diplomacy with political parties during national elections. NERGs also respond to incidences of harassment, intimidation and violence; work towards keeping communities calm and organised; and engage with all political groups to keep the peace. This article discusses the development and operationalisation of NERGs as an infrastructure for peace during recent elections in some West African countries.

Elections and Violence in West Africa

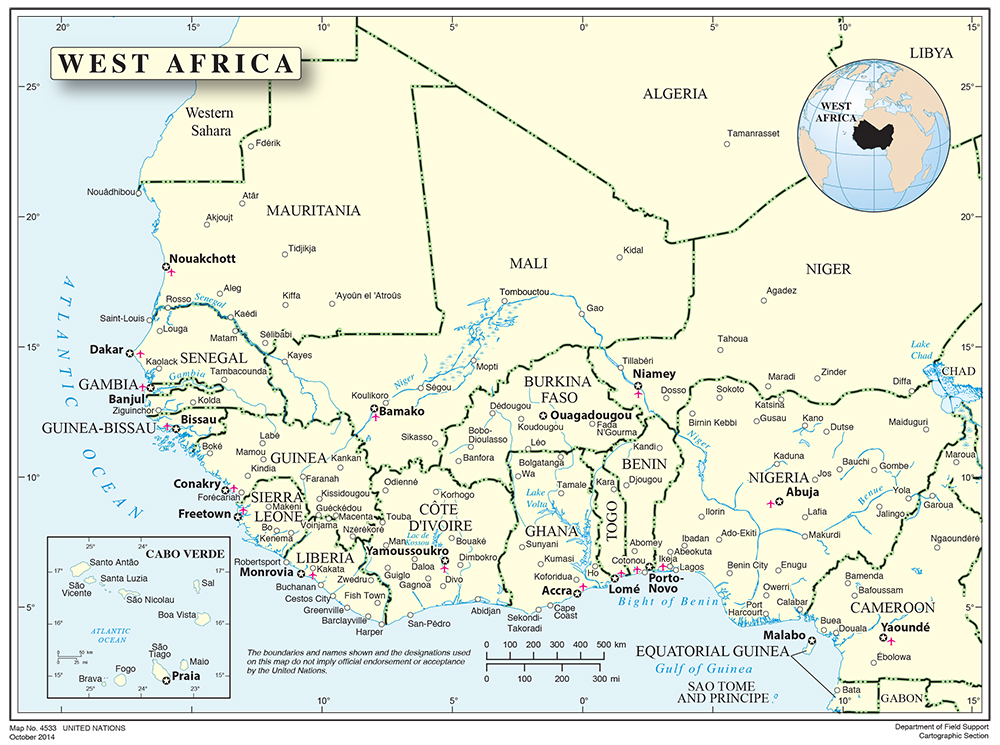

West African countries have seen a fair share of election-related conflicts, some of which led to large-scale violence – such as in Nigeria in 2007, Guinea in 2010 and Senegal in 2012 – and others that led to civil war – for example, in Côte d’Ivoire in 2010–2011. Other countries that have been embroiled in electoral violence in the subregion include Togo, during its presidential elections in 2005; Ghana in 2012; and, most recently, presidential elections in The Gambia in 2016.1 These cases are notable for the scale of violence perpetuated by political opponents during the election cycle. However, there are reports of incidences of harassment and intimidation, or small-scale clashes between opposing political groups, in almost all elections that take place in the subregion.

Elections, rather than being a vehicle for peaceful democratic transitions, have also become a conflict-triggering factor as a result of deep divisions among various social and political groups that manifest in open confrontation and violence – including verbal, physical, psychological, structural and institutional violence – during periods of elections. There is always some act of violence at any given point before or during general elections, as well as after results have been announced. Added to this, deficiencies in the political, social and economic spaces of communities in West Africa represent existential risk factors that have the potential to generate conflict during election cycles.

One of the major challenges for peaceful democratic transition of governments in the subregion – and even across other countries in Africa – has been the desire of incumbent leaders to hold on to political office.2 In pursuing this agenda, they suppress and oppress opposition groups, kill and exile political opponents and undertake unconstitutional actions that generate grievances and frustrations, which inevitably lead to violent confrontations during elections. A one-party system of government was the catalyst for the civil war in Sierra Leone between 1991 and 2002. Overstaying in power by the late president Lansana Conté of Guinea created political instability in the country, further fuelling conflict in the Mano River Basin throughout the 1990s. More recently, attempts were made by the long-term president of Burkina Faso, Blaise Compaoré, to run for a third term in 2014, but he was unsuccessful after huge demonstrations during elections. Similar attempts were made in 2009 by President Mamadou Tandja of Niger to change the constitution and run for a third term. He was later ousted. Nigeria has attempted to remove presidential term limits and failed. Similar cases were evident in The Gambia and Togo.

The Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) provides technical and financial assistance to all member states during their election cycle. (Reuters/Luc Gnago)

The Economic Community of West Africa States (ECOWAS), serving as the subregion’s intergovernmental body, has worked on normative frameworks and operationalised policies with member states towards the peaceful democratic transition of governments. In certain instances, ECOWAS pursued diplomatic means to bring an end to electoral standoffs in some countries. The most recent case was the 2016 election in The Gambia. In December 2001, ECOWAS member states adopted the Supplementary Protocol on Democracy and Good Governance. This protocol requires member states to take stronger measures that strengthen constitutional legitimacy for better democratic practices and presents a stronger case against unconstitutional accession to power, thereby establishing a new agenda for democratic governance based on the conduct of peaceful and credible elections that are free, fair and transparent.3

In 2006, ECOWAS established an Electoral Assistance Division (EAD) to provide technical and financial assistance to all member states during their election cycle. During elections in each member state, the ECOWAS Commission undertakes pre-election consultations with governments, political parties, election management bodies and other key stakeholders to assess the country’s preparedness, as well as to provide needed technical support to scale up effective conduct of the election. On election day, ECOWAS observers are deployed, working with all political groups and the election management structures to ensure a peaceful outcome of the election process. One such structure that has emerged in recent years is the NERG.

Operationalisation of National Election Response Groups in West Africa

A NERG comprises a group of institutions that converge to form a collaborative platform, tasked with the responsibility of responding to potential or existential threats of violence during the election cycle in a given state. It involves the coming together of state and non-state institutions and other relevant actors, including national civil society structures, to respond to potential or actual threats of violence during the organising and conduct of a general election. The group is usually inclusive of religious and traditional leaders, representatives of major civil society institutions, non-governmental organisations (NGOs), the security apparatus, international organisations working on election-related issues, the government and political groups.

A NERG is designed as a platform for collective action in responding to incidences that may create tensions and violence during and after election day. The idea of NERGs was developed by the West Africa Network for Peacebuilding (WANEP), based in Accra, Ghana, as part of its thematic project on mitigating electoral violence through national early warning systems.4

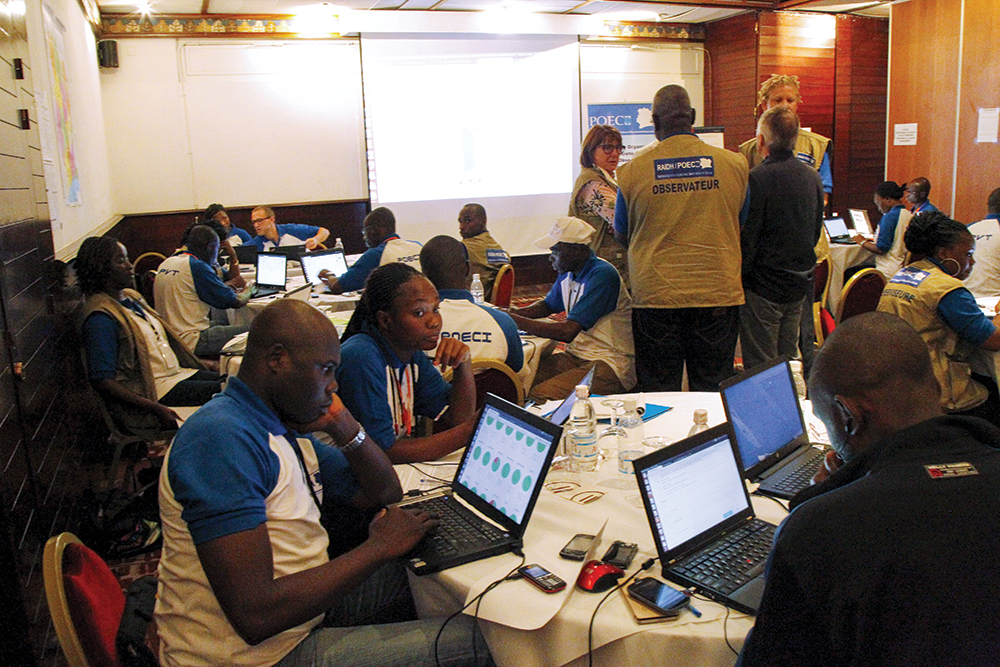

A NERG does not operate in a vacuum. Before institutions are identified and converge to begin the process of mitigating possible election violence, election situation rooms (ESRs) are operationalised. An ESR includes monitors and observers, who report election-related incidences in communities. This information is collected and collated by an information-gathering team, who cross-check and authenticate the reports from observers. These reports are then evaluated by a group of analysts responsible for drafting various scenarios of outcomes related to the incidents reported and making recommendations on immediate steps to resolve the incidents peacefully. These recommendations are passed on to the NERG, to use its vast network of national and local institutions to respond to such incidents in a manner that will lead to political compromise and resolution.

In finding solutions, a NERG brings all its resources to bear. It meets political parties; alerts the police on security matters; requests information and clarification from the election management bodies geared towards preventing any form of electoral malpractice; requests the presence of heads of political parties to find solutions to election-related grievances; and engages in consultations with key international observer missions, such as the African Union (AU) and ECOWAS mission, in the management of election-related incidences. Consultation, dialogue and mediation are some of the key conflict-handling mechanisms employed by a NERG in its pursuit of maintaining peace during elections.

The National Election Response Group in Sierra Leone

Sierra Leone conducted four sets of elections in March 2018. These included presidential, parliamentary, mayoral and local council elections. This was also the first major election cycle that was fully funded by the Government of Sierra Leone with no major donor support since the start of its post-conflict democratisation process in 2002. The pre-election period was overshadowed by various controversial issues. The first issue was a constitutional review process, wherein an attempt was made to increase the presidential term limit – but this was quickly rejected by the review committee. In addition, there were reports of discrepancies over constituency demarcations a few months before the elections. The main opposition party, the Sierra Leone People’s Party (SLPP), complained that the demarcation process was done in favour of the incumbent government of the All People’s Congress Party (APC).

Also, a few months before the elections, the incumbent government interpreted a law in the constitution that prevents people with dual citizenship from holding political office. This includes contesting the presidency and holding ministerial and parliamentary positions. This law was brought to the fore to prevent some candidates from contesting the elections. This heightened political tensions and led to incidents of violent confrontation among supporters of the major political parties. In addition, divisive political campaigns based on ethnicity and regionalism was a cause for concern.

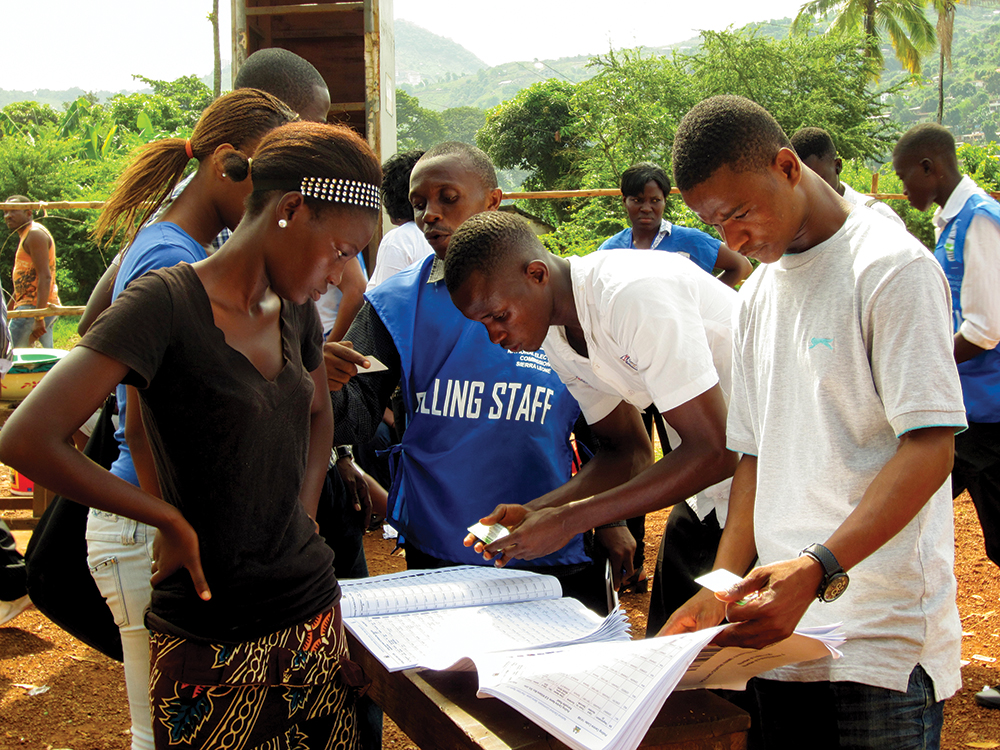

After mapping out the potential hotspots for electoral violence, WANEP and its civil society partners establish ed a NERG and a District Election Response Group (DERG). In collaboration with the National Election Watch (NEW) of Sierra Leone, WANEP trained and deployed 500 accredited observers in prioritised risk areas across the 16 districts of Sierra Leone. The NERG in Sierra Leone is composed of civil society organisations (CSOs), government and non-governmental institutions, faith-based groups, security agencies, women and youth groups, and the media.

On election day, the NERG, with the support of observers and analysts within the ESR, deliberated and consulted with all political parties, the security apparatus and the National Electoral Commission, to respond to incidences of electoral violence. It also engaged in consultations with local communities to discuss their concerns as a way of mitigating violent confrontations between opposing groups. The election process concluded peacefully, with few incidences of violence, and with the election of Julius Maada Bio of the SLPP as the new president.5

Liberia Elections Early Warning and Response Group

The election process in Liberia in October and December 2017 had its fair share of challenges. The first round of elections took place on 10 October 2017. The ruling Unity Party, led by incumbent vice president, Joseph Boakai, and the opposition Coalition for Democratic Change, led by George Oppong Weah, failed to gain an outright majority, leading to a run-off election. However, on 6 November 2017, a day before the run-off election was to be held, the Supreme Court of Liberia ruled that the election should not go ahead until allegations of voter fraud and irregularities made by the third-placed Liberty Party were addressed. The Liberty Party requested a rerun of the first vote, but was dismissed by the court.6 This heightened political tensions, with incidences of violent confrontations between supporters of the major political parties. After the announcement of a new date (26 December 2017) for the run-off election, WANEP – in collaboration with the government, civil society partners and the ECOWAS commission – operationalised the Liberia Elections Early Warning and Response Group (LEEWARG).

LEEWARG had a similar structure to the NERG in Sierra Leone, with actors drawn from faith-based groups, security agencies, major CSOs and the media. It was operationalised with an ESR stationed at the ECOWAS Commission office in Monrovia, and deployed 43 monitors – in addition to other accredited observers – in all 17 electoral districts across the 15 counties of Liberia. LEEWARG had representatives from the ECOWAS Commission, AU observer mission, National Traditional Council, National Civil Society Council of Liberia, Office of the Peace Ambassador of Liberia, Liberia Peacebuilding Office, the Elections Coordinating Committee, the National Security Council Secretariat, the National Center for the Coordination of Response Mechanisms and the Inter-religious Council of Liberia.

All these institutions were part of an inclusive process that pursued preventive diplomacy, where incidences were reported of perceived or active confrontations between supporters of the major political parties.7

National Elections Early Warning and Response Group in Ghana

On 26 July 2016, almost six months before the general election was conducted in Ghana, a National Elections Early Warning and Response Group (NEEWARG) was launched in Accra by WANEP, in partnership with the National Peace Council (NPC) of Ghana, the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) and the United Nations Development Programme. Other institutional partnerships that formed the NEEWARG were Ghana’s Commission for Human Rights and Administrative Justice, the Kofi Annan Peacekeeping Training Centre, Legon Centre for International Affairs and Diplomacy, and the Transform Ghana Network.

In operationalising the NEEWARG, an ESR was established in Accra, whilst satellite situation rooms were located in Kumasi to cover the Ashanti and Brong Ahafo regions and Tamale to cover the Northern, Upper-East and Upper-West regions of Ghana. From 6 to 10 December 2016, 750 accredited local observers were deployed in prioritised risk areas across Ghana’s 10 regions, whilst 75 personnel formed part of the operational team of the NEEWARG-ESR.8

The eminent persons group, led by the chairperson of the National Peace Council of Ghana, undertook shuttle diplomacy, reaching out to all political parties to consult and dialogue with them and their supporters to address incidences of irregularities in the voting process, as well as incidences of political tensions. A good example was a case in Kumasi, where the situation room worked with the Regional Peace Council in Brong Ahafo to calm tensions over the postponement of voting in Jaman North.9

National Election Response Groups as Infrastructures for Peace

Infrastructure for peace (I4P) is a fairly new concept in the domain of peace research and in the practice of peacebuilding. It is an evolving concept that is slowly gaining wider currency. John Paul Lederach first introduced the concept in the 1990s in his pioneering work, Building Peace: Sustainable Reconciliation in Divided Societies. He posits that an organised conflict transformation process must consist of a functional network of different sets of local and national actors, who forge collaborative interaction geared towards tackling the threat of conflicts and use their platform to constructively build peace in society.10

I4P is an organised system of interaction among and between institutions or groups forging ties of cooperation, and takes on activities and programmes that are responsive to crisis situations at its latent stage, during its escalation point and during its transformation to peaceful social relations. I4Ps do not only come about through institutional interaction, but can be developed by means of policies and institutional norms, rules and regulations that shape the actions and inactions of people, and through groups and communities that foster peaceful social relations in society.11

A NERG as an I4P is a collaborative approach in mitigating existential risk factors in times of elections, such as political tensions and confrontations between groups of major political parties, incidences of violence and complaints of voting irregularities on election day. Similarly, a NERG is a cooperative and inclusive process that brings together a broad range of actors and institutions to mitigate violence during election cycles to keep the peace.12 Like I4P, a NERG is a structure that coordinates and supports constructive problem-solving processes through dialogue, consultations and shuttle diplomacy, linking local and national actors at all levels to reach common ground in responding to incidences that have the potential to disrupt the peaceful conduct of elections in any given state.

A NERG comprises of institutions as actors, undertakes dialogue and shuttle diplomacy as its method of engagement, and is operationalised through a situation room, with analysts and observers as part of its structure. It has a central body that takes a full leadership role, connecting national and local partners in peaceful dialogue during elections. A NERG also works with all political parties, the voting population, security agencies, the government and non-governmental institutions to keep the peace in times of elections.

Concluding Remarks

Beyond the three country cases that have been discussed, NERGs have also been established in Niger and Burkina Faso, and plans are ongoing for their establishment in Nigeria and The Gambia for the monitoring and mitigation of election-related conflicts during the next election cycle in these countries. With their successful operationalisation in West Africa, NERGs represent an inclusive, holistic, local mechanism that can be applied to mitigate violence in the conduct of elections across other regional subsystems in Africa.

Endnotes

- UNOWAS (2017) Understanding Electoral Violence to Better Prevent E-Magazine, p. 5, Available at: <https://unowas.unmissions.org/understanding-electoral-violence-better-prevent-it> [Accessed 10 October 2018].

- Burchard, Stephanie (2015) Electoral Violence in Sub-Saharan Africa: Causes and Boulder CO: FirstForumPress (Lynne Rienner Publishers).

- ECOWAS (2001) Supplementary Protocol on Democracy and Good Governance. Abuja: ECOWAS

- WANEP (2018) ‘Quarter One Report 2018’, 3, Available at: <www.wanep.org> [Accessed 10 October 2018].

- Ibid.

- Al Jazeera (2017) ‘Liberia Election: George Weah v Joseph Boakai’, 27 December, Available at: <https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2017/12/liberia-election-george-weah-joseph-boakai-171226183557370.html> [Accessed 5 October 2018].

- WANEP (2017) Press Statement of the LEEWARG Elections Situation Room, 2, Available at: <http://www.wanep.org/wanep/files/2017/oct/1st_Press_Statement_ESR_Liberia.pdf> [Accessed October 2018].

- WANEP (2016a) ‘Annual Report’, p. 11, Available at: <www.wanep.org>[Accessed 15 October 2018].

- WANEP (2016b) ‘The Coordinated Elections Situation Room for Ghana 2016 General Elections, Comprehensive Report’, 4, Available at: <http://www.wanep.org/wanep/files/2017/mar/rp_coordinated_ESR_Ghana_.pdf> [Accessed 15 October 2018].

- Lederach, John Paul (1997) Building Peace: Sustainable Reconciliation in Divided Washington: United States Institute of Peace, pp. 112–127.

- Lederach, John Paul (2012) The Origins and Evolution of Infrastructures for Peace: A Personal Journal of Peacebuilding and Development, 7 (3), pp. 8–14.

- Van Tongeren, Paul (2011) Increasing Interest in Infrastructures for Peace. Journal of Conflictology, 2, pp. 45–55.